Allergy: the Body As Self-Evidence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Genetic Basis of Interindividual Variability in the Course of Infection

Human genetic basis of interindividual variability in the course of infection Jean-Laurent Casanovaa,b,c,d,e,1 aSt. Giles Laboratory of Human Genetics of Infectious Diseases, Rockefeller Branch, The Rockefeller University, New York, NY 10065; bHoward Hughes Medical Institute, New York, NY 10065; cLaboratory of Human Genetics of Infectious Diseases, Necker Branch, Inserm U1163, Necker Hospital for Sick Children, 75015 Paris, France; dImagine Institute, Paris Descartes University, 75015 Paris, France; and ePediatric Hematology and Immunology Unit, Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris, Necker Hospital for Sick Children, 75015 Paris, France This contribution is part of the special series of Inaugural Articles by members of the National Academy of Sciences elected in 2015. Contributed by Jean-Laurent Casanova, November 2, 2015 (sent for review September 15, 2015; reviewed by Max D. Cooper and Richard A. Gatti) The key problem in human infectious diseases was posed at the immunity (cell-autonomous mechanisms), then of cell-extrinsic turn of the 20th century: their pathogenesis. For almost any given innate immunity (phagocytosis of pathogens by professional cells), virus, bacterium, fungus, or parasite, life-threatening clinical disease and, finally, of cell-extrinsic adaptive immunity (somatic di- develops in only a small minority of infected individuals. Solving this versification of antigen-specific cells). Understanding the patho- infection enigma is important clinically, for diagnosis, prognosis, genesis of infectious diseases, particularly -

Xii World Asthma, Allergy & Copd Forum

XII WORLD ASTHMA, ALLERGY & COPD FORUM Saint Petersburg, Russia June 29–July 2, 2019 SAINT PETERSBURG SAINT PROGRAM World Immunopathology XIII WORLD ASTHMA, Organization (WIPO) ALLERGY & COPD FORUM Saint-Petersburg, Russia July 2–5, 2020 General Information St. Pet The World Immunopathology Organization (WIPO) is a professional, non-profit organization. WIPO was created in December 2002, at the I World Congress on Immunopathology in Singapore. During these years, WIPO successfully organized many international congresses and regional and national meetings throughout See you in Saint Petersburg in 2020! the world all promoting basic and clinical research and giving an opportunity for exchanging ideas. WIPO is aimed at collecting and disseminating scientific information and providing training and continuous education in various fields of immunopathology. Aims and Mission Nowadays, immunopathology has become a multidisciplinary problem. The WIPO global mission is to promote through education and research activities worldwide: – basic and clinical research in experimental and clinical immunology, allergy and asthma, autoimmunity, immunodeficiency, AIDS, immunobiotechnology, – prevention and treatment of different manifestations of immunopathology—immune-associated disorders, – excellence in patient care in this very important area of medicine and to establish communication between specialists in various fields of medical science and practice. e We encourage to join WIPO national and regional societies as well as individual members—doctors -

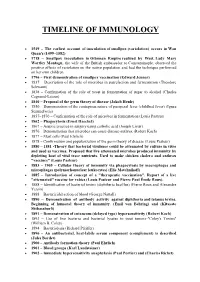

Timeline of Immunology

TIMELINE OF IMMUNOLOGY 1549 – The earliest account of inoculation of smallpox (variolation) occurs in Wan Quan's (1499–1582) 1718 – Smallpox inoculation in Ottoman Empire realized by West. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, the wife of the British ambassador to Constantinople, observed the positive effects of variolation on the native population and had the technique performed on her own children. 1796 – First demonstration of smallpox vaccination (Edward Jenner) 1837 – Description of the role of microbes in putrefaction and fermentation (Theodore Schwann) 1838 – Confirmation of the role of yeast in fermentation of sugar to alcohol (Charles Cagniard-Latour) 1840 – Proposal of the germ theory of disease (Jakob Henle) 1850 – Demonstration of the contagious nature of puerperal fever (childbed fever) (Ignaz Semmelweis) 1857–1870 – Confirmation of the role of microbes in fermentation (Louis Pasteur) 1862 – Phagocytosis (Ernst Haeckel) 1867 – Aseptic practice in surgery using carbolic acid (Joseph Lister) 1876 – Demonstration that microbes can cause disease-anthrax (Robert Koch) 1877 – Mast cells (Paul Ehrlich) 1878 – Confirmation and popularization of the germ theory of disease (Louis Pasteur) 1880 – 1881 -Theory that bacterial virulence could be attenuated by culture in vitro and used as vaccines. Proposed that live attenuated microbes produced immunity by depleting host of vital trace nutrients. Used to make chicken cholera and anthrax "vaccines" (Louis Pasteur) 1883 – 1905 – Cellular theory of immunity via phagocytosis by macrophages and microphages (polymorhonuclear leukocytes) (Elie Metchnikoff) 1885 – Introduction of concept of a "therapeutic vaccination". Report of a live "attenuated" vaccine for rabies (Louis Pasteur and Pierre Paul Émile Roux). 1888 – Identification of bacterial toxins (diphtheria bacillus) (Pierre Roux and Alexandre Yersin) 1888 – Bactericidal action of blood (George Nuttall) 1890 – Demonstration of antibody activity against diphtheria and tetanus toxins. -

Hans Asperger, National Socialism, and “Race Hygiene” in Nazi-Era Vienna Herwig Czech

Czech Molecular Autism _#####################_ https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-018-0208-6 RESEARCH Open Access Hans Asperger, National Socialism, and “race hygiene” in Nazi-era Vienna Herwig Czech Abstract Background: Hans Asperger (1906–1980) first designated a group of children with distinct psychological characteristics as ‘autistic psychopaths’ in 1938, several years before Leo Kanner’s famous 1943 paper on autism. In 1944, Asperger published a comprehensive study on the topic (submitted to Vienna University in 1942 as his postdoctoral thesis), which would only find international acknowledgement in the 1980s. From then on, the eponym ‘Asperger’s syndrome’ increasingly gained currency in recognition of his outstanding contribution to the conceptualization of the condition. At the time, the fact that Asperger had spent pivotal years of his career in Nazi Vienna caused some controversy regarding his potential ties to National Socialism and its race hygiene policies. Documentary evidence was scarce, however, and over time a narrative of Asperger as an active opponent of National Socialism took hold. The main goal of this paper is to re-evaluate this narrative, which is based to a large extent on statements made by Asperger himself and on a small segment of his published work. Methods: Drawing on a vast array of contemporary publications and previously unexplored archival documents (including Asperger’s personnel files and the clinical assessments he wrote on his patients), this paper offers a critical examination of Asperger’s life, politics, and career before and during the Nazi period in Austria. Results: Asperger managed to accommodate himself to the Nazi regime and was rewarded for his affirmations of loyalty with career opportunities. -

EXPERIMENTAL ENCEPHA.LOMYELITIS Current Problems in Allergy and Immunology

362 JuLY 30, 1960 REVIEWS BRrm= _M IC JO formulae to permit a detailed description of enzyme Many European countries are represented as well as mechanisms. The presentation follows to some extent Australia and South Africa, but the majority of the the pattern of Professor Baldwin's earlier Dynamic contributors are from North America. This latter is Aspects, which also originated in the Cambridge School not surprising, for Dr. Schick's work and personality of Biochemistry, but is in a more condensed form. the have undoubtedly had a considerable influence on the very short chapter on control of metabolism is study of allergy in the land of his adoption. stimulating, and suggests the hope of future progress. The subjects vary widely, with the emphasis, as one The second book, by Dr. Dawkins and Dr. Rees, reads would expect, on aspects of allergy affecting children rather like a continuation of the first, and is particularly as well as on the experimental side of allergy. Side-by- concerned with the nature of metabolic disturbances side are such diverse subjects as an appraisal of sero- from the cellular angle, with special reference to the logical reactions in rheumatoid arthritis by Sulkin and effects of toxins and of deficiency states, both congenital Pvke, and food-induced aitergic illness in children by and acquired. Both authors work at University College Kaufman; liver disease and antibody formation by Hospital Medical School, and their outlook no doubt Havens, and musculo-skeletal allergy, in children by reflects the interest in the subject of Sir Roy Cameron Randolph; the influence of bacterial polysaccharides to whom the book is dedicated. -

Clemens Freiherr Von Pirquet and the Tuberculin Test

INT J TUBERC LUNG DIS 7(12):1115–1116 FOUNDERS OF OUR KNOWLEDGE © 2003 IUATLD Clemens Freiherr von Pirquet and the tuberculin test IN FEBRUARY 1909, Clemens von Pirquet pub- lished a seminal article in the Journal of the American Medical Association in which he described an intra- dermal tuberculin skin test.1 In this paper, von Pirquet not only described his pioneering first use of intrader- mal tuberculin testing, but he also reported the re- markable insights into the pathogenesis of tubercu- losis that he gained from his observations of tuberculin reactions in children. By any measure, Clemens Freiherr von Pirquet was a remarkable individual.2,3 The youngest son of a bar- onet (hence the title Freiherr), he was born on 12 May 1874 on the estate of his family at Hirschstetten near Vienna, Austria. As he had no hope of inheriting fam- ily land, he began to study for the priesthood. During a pilgrimage to Lourdes in 1894 he apparently had an Figure Clemens Freiherr von Pirquet. Pencil drawing by Theresa epiphany and decided to abandon religion and study S K Chung. Reproduced with permission from Daniel, T M (ref- erence 3). medicine, a profession his disapproving family deemed unworthy for a man of his social status. He received his medical degree from the University of Graz in The tuberculin test paper published in JAMA in 1900. After 6 months of further study in Berlin, he 1909 is a true landmark. Preceded several months undertook further training with Theodur Escherich at earlier by presentations at medical meetings and brief the Universitäts Kinderklinik of the St Anna Chil- journal reports, this elegant exposition begins by not- dren’s Hospital in Vienna. -

Immunology of the Allergic Response 1

9781405157209_4_001.qxd 4/1/08 20:03 Page 1 1 Immunology of the Allergic Response 9781405157209_4_001.qxd 4/1/08 20:03 Page 2 .. 9781405157209_4_001.qxd 4/1/08 20:03 Page 3 1 Allergy and Hypersensitivity: History and Concepts A. Barry Kay Summary The study of allergy (“allergology”) and hypersensitivity, and the associated allergic diseases, have their roots in the science of immunology but overlap with many disciplines including pharmacology, biochemistry, cell and molecular biology, and general pathology, particularly the study of inflammation. Allergic diseases involve many organs and tissues such as the upper and lower airways, the skin, and the gastrointestinal tract and therefore the history of relevant discoveries in the field are long and complex. This chapter gives only a brief account of the major milestones in the history of allergy and the concepts which have arisen from them. It deals mainly with discoveries in Fig. 1.1 A commemorative postage stamp to mark the discovery the 19th and early 20th century, particularly the events which of anaphylaxis by Charles R. Richet (1850–1935) and Paul J. Portier followed the description of anaphylaxis and culminated in the (1866–1962). discovery of IgE as the carrier of reaginic activity. An important conceptual landmark that coincided with the considerable foreign proteins to various species including dogs (Magendie increase in knowledge of immunologic aspects of hypersensitivity 1839), guinea pigs (Von Behring 1893, quoted in Becker 1999, was the Coombs and Gell classification of hypersensitivity p. 876) and rabbits (Flexner 1894, reviewed in Bulloch 1937). reactions in the 1960s. This classification is revisited and updated However it was not until the discovery of anaphylaxis by to take into account some newer finding on the initiation of the allergic response. -

Human Genetic Basis of Interindividual Variability in the Course of Infection

Human genetic basis of interindividual variability in the course of infection Jean-Laurent Casanovaa,b,c,d,e,1 aSt. Giles Laboratory of Human Genetics of Infectious Diseases, Rockefeller Branch, The Rockefeller University, New York, NY 10065; bHoward Hughes Medical Institute, New York, NY 10065; cLaboratory of Human Genetics of Infectious Diseases, Necker Branch, Inserm U1163, Necker Hospital for Sick Children, 75015 Paris, France; dImagine Institute, Paris Descartes University, 75015 Paris, France; and ePediatric Hematology and Immunology Unit, Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris, Necker Hospital for Sick Children, 75015 Paris, France This contribution is part of the special series of Inaugural Articles by members of the National Academy of Sciences elected in 2015. Contributed by Jean-Laurent Casanova, November 2, 2015 (sent for review September 15, 2015; reviewed by Max D. Cooper and Richard A. Gatti) The key problem in human infectious diseases was posed at the immunity (cell-autonomous mechanisms), then of cell-extrinsic turn of the 20th century: their pathogenesis. For almost any given innate immunity (phagocytosis of pathogens by professional cells), virus, bacterium, fungus, or parasite, life-threatening clinical disease and, finally, of cell-extrinsic adaptive immunity (somatic di- develops in only a small minority of infected individuals. Solving this versification of antigen-specific cells). Understanding the patho- infection enigma is important clinically, for diagnosis, prognosis, genesis of infectious diseases, particularly -

20190214 PDF Evolving Concepts of Allergy

Evolving concepts of allergy Further reading The concept of allergy evolved and more and more new phenomena were described and documented in the beginning of the 20th century. Nowadays, we are able to classify them based on the different cellular mechanisms underlying the distinct reactions. Read below how Type III and IV allergic reactions were discovered. Arthus reaction (nowadays Type III allergic reaction) In 1903, the French physiologist Nicolas Maurice Arthus observed local skin reactions (i.e. redness, swelling, overheated tissue and later necrosis) after subcutaneously injecting repeated doses of sterile horse serum in his patients. This actually resembled the classical signs of any skin inflammation. Surprisingly, this reaction occurred after injection of non-infectious and non-toxic substances. He called the phenomenon ‘local anaphylaxis’. Today it is known to be caused by an immune complex reaction (type III allergic reaction by Coombs and Gell). It still may happen today in individuals with high titers of protective IgG anti-tetanus antibodies. If they receive another dose of tetanus toxoid in case of a contaminated wound, the high antibody concentration interacting with the locally injected antigen form immune complexes resulting in a large local reaction (sometimes accompanied by fever). Delayed hypersensitivity (nowadays Type IV allergic reaction) Eczemas have already been known by the ancient Greeks. The word ‘eczema’ means to burn or boil and refers to the itchy and burning skin eruptions. Before the concept of allergy was established, the term ‘Dermatitis venenata’ was coined by the American Charles White in 1887. Different skin reactions upon contact with plants (including poison ivy, lacquer or primula) have been documented at that time. -

Immunology in Austria – Past and Present

Immunology in Austria – Past and Present History . At the time of the first surge of immunology during the second half of the 19 th and the beginning of the 20 th century Austrian physicians have made important contributions to this emerging new science. Rudolf Kraus was first to describe the precipitation reaction occurring after mixing soluble antigen with a specific antiserum. Max von Gruber contributed to the application of bacterial agglutination as a diagnostic tool (Gruber-Widal test). Karl Landsteiner, studying hemagglutination by sera from individual persons, discovered the ABO blood group system, made important observations in the serodiagnosis of syphilis and in 1904 described the first autoantibody and thus the first autoimmune disease, the paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria. Ernst Peter Pick modified proteins by attaching simple chemicals and showed that after their injection in animals they produced antibodies specific for the chemical (later termed hapten by Landsteiner). Löwenstein and Eisler-Terramare made the important observation, that bacterial toxins could be inactivated by formaldehyde without loosing their antigenicity. These were called toxoids and used for the immunization of animals as well as humans. Another outstanding immunologist of this period was Clemens von Pirquet, a pediatrician, well known for coining the term "allergy" in 1906. He also made important studies on serum sickness, developed a skin test for tuberculosis – the tuberculin reaction – and together with Schick, a skin test for diphtheria. Two world wars significantly impaired Austria's capacity in immunological research. Landsteiner left Austria in 1919, Ernst Peter Pick was exiled in 1938 after the "Anschluss", and Eisler-Terramare was detained in a concentration camp. -

Theodor Escherich: the First Pediatric Practice Was Essentially Limited to the Health and Illnesses of Children

MISCELLANY Theodor Escherich: The First Pediatric practice was essentially limited to the health and illnesses of children. In addition, specific training in a scientific discipline, Infectious Diseases Physician? such as microbiology, bacteriology, immunology, infectious dis- eases, and/or epidemiology, is a reasonable criterion. Additional Stanford T. Shulman,1 Herbert C. Friedmann,3 and Ronald H. Sims2 criteria should probably include an enduring commitment to 1Department of Pediatrics, Division of Infectious Diseases, Children’s Memorial the training of pediatricians with interest in infectious diseases Hospital, and 2Galter Health Sciences Library, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, and 3Department of Biochemistry and Molecular of children and significant scientific contributions that im- Biology, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois proved the understanding, therapy, and/or prevention of in- fectious diseases of childhood. Theodor Escherich (1857–1911). Theodor Escherich (fig- The career of Theodor Escherich (1857–1911) qualifies him ure 1) was born on 29 November 1857 in Ansbach, Germany, as the first pediatric infectious diseases physician. His land- to Dr. Ferdinand Escherich (1810–1880), the district medical mark bacteriologic studies identified the common colon ba- officer of health and a noted medical statistician, and his third cillus (now known as Escherichia coli), and he was very com- wife, Maria Sophie Frieder, daughter of a Bavarian army colo- mitted to pediatrics, serving as chairman of several nel. Dr. F. Escherich was concerned about high neonatal mor- prominent departments of pediatrics, including the Depart- tality rates, as well as health care for the poor, about which ment of Pediatrics at the University of Vienna and St. -

Computationally Grafting an Ige Epitope Onto a Scaffold

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.14.296392; this version posted September 15, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. BioRxiv 15 September 2020 Computationally Grafting An IgE Epitope Onto A Scaffold Sari Sabban1* Abstract Due to the increased hygienic life style of the developed world allergy is an increasing disease. Once allergy develops, sufferers are permanently trapped in a hyper immune response that makes them sensitive to innocuous substances. This paper discusses the strategy and protocol employed which designed proteins displaying a human IgE motif very close in proximity to the IgE’s FceRI receptor binding site. The motif of interest was the FG motif and it was excised and grafted onto the protein scaffold 1YN3. The new structure (scaffold + motif) was fixed-backbone sequence designed around the motif to find an amino acid sequence that would fold to the designed structure correctly. Ten computationally designed proteins showed successful folding when simulated using the AbinitioRelax folding simulation and the IgE epitope was clearly displayed in its native three dimensional structure in all of them. Such a designed protein has the potential to be used as a pan anti-allergy vaccine by guiding the immune system towards developing antibodies against this strategic location on the body’s own IgE molecule, thus neutralising it and presumably permanently shutting down a major aspect of the Th2 immune pathway. Keywords Protein Design — Epitope Grafting — Vaccine Design — Computational Structural Biology — Allergy — Type I Hypersensitivity 1Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Makka, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia *Corresponding author: [email protected] Introduction from allergic manifestations began in the second half of the last century and the incidence of allergy has now reached Allergy was first defined by Clemens von Pirquet in 1906 pandemic proportions [20].