Germs, Vaccines, and the Rise of Allergy Carla C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Genetic Basis of Interindividual Variability in the Course of Infection

Human genetic basis of interindividual variability in the course of infection Jean-Laurent Casanovaa,b,c,d,e,1 aSt. Giles Laboratory of Human Genetics of Infectious Diseases, Rockefeller Branch, The Rockefeller University, New York, NY 10065; bHoward Hughes Medical Institute, New York, NY 10065; cLaboratory of Human Genetics of Infectious Diseases, Necker Branch, Inserm U1163, Necker Hospital for Sick Children, 75015 Paris, France; dImagine Institute, Paris Descartes University, 75015 Paris, France; and ePediatric Hematology and Immunology Unit, Assistance Publique–Hôpitaux de Paris, Necker Hospital for Sick Children, 75015 Paris, France This contribution is part of the special series of Inaugural Articles by members of the National Academy of Sciences elected in 2015. Contributed by Jean-Laurent Casanova, November 2, 2015 (sent for review September 15, 2015; reviewed by Max D. Cooper and Richard A. Gatti) The key problem in human infectious diseases was posed at the immunity (cell-autonomous mechanisms), then of cell-extrinsic turn of the 20th century: their pathogenesis. For almost any given innate immunity (phagocytosis of pathogens by professional cells), virus, bacterium, fungus, or parasite, life-threatening clinical disease and, finally, of cell-extrinsic adaptive immunity (somatic di- develops in only a small minority of infected individuals. Solving this versification of antigen-specific cells). Understanding the patho- infection enigma is important clinically, for diagnosis, prognosis, genesis of infectious diseases, particularly -

Continuous Time Individual-Level Models of Infectious Disease: Epiilmct

Continuous Time Individual-Level Models of Infectious Disease: EpiILMCT Waleed Almutiry Vineetha Warriyar K V Rob Deardon Qassim University Uinversity of Calgary University of Calgary Abstract This paper describes the R package EpiILMCT, which allows users to study the spread of infectious disease using continuous time individual level models (ILMs). The package provides tools for simulation from continuous time ILMs that are based on either spatial demographic, contact network, or a combination of both of them, and for the graphical summarization of epidemics. Model fitting is carried out within a Bayesian Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) framework. The continuous time ILMs can be implemented within either susceptible-infected-removed (SIR) or susceptible- infected-notified-removed (SINR) compartmental frameworks. As infectious disease data is often partially observed, data uncertainties in the form of missing infection times - and in some situations missing removal times - are accounted for using data augmentation techniques. The package is illustrated using both simulated and an experimental data set on the spread of the tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV) disease. Keywords: EpiILMCT, infectious disease, individual level modelling, spatial models, con- tact networks, R. 1. Introduction Innovative mathematical and mechanistic approaches to the modelling of infectious dis- eases are continuing to emerge in the literature. These can be used to understand the spread of disease through a population - whether homogeneous or heterogeneous - and enable researchers to construct predictive models to develop control strategies to disrupt arXiv:2006.00135v1 [stat.AP] 30 May 2020 disease transmission. For example, Deardon et al. (2010) introduced a class of discrete time individual-level models (ILMs) which incorporate population heterogeneities by modelling the transmission of disease given various individual-level risk factors. -

The Basic Reproduction Number As a Predictor for Epidemic Outbreaks in Temporal Networks

The basic reproduction number as a predictor for epidemic outbreaks in temporal networks Petter Holme1,2,3 and Naoki Masuda4 1Department of Energy Science, Sungkyunkwan University, 440-746 Suwon, Korea 2IceLab, Department of Physics, Umeå University, 90187 Umeå, Sweden 3Department of Sociology, Stockholm University, 10961 Stockholm, Sweden 4Department of Engineering Mathematics, University of Bristol, BS8 1UB, Bristol, UK E-mail address: [email protected] Abstract The basic reproduction number R₀—the number of individuals directly infected by an infectious person in an otherwise susceptible population—is arguably the most widely used estimator of how severe an epidemic outbreak can be. This severity can be more directly measured as the fraction people infected once the outbreak is over, Ω. In traditional mathematical epidemiology and common formulations of static network epidemiology, there is a deterministic relationship between R₀ and Ω. However, if one considers disease spreading on a temporal contact network—where one knows when contacts happen, not only between whom—then larger R₀ does not necessarily imply larger Ω. In this paper, we numerically investigate the relationship between R₀ and Ω for a set of empirical temporal networks of human contacts. Among 31 explanatory descriptors of temporal network structure, we identify those that make R₀ an imperfect predictor of Ω. We find that descriptors related to both temporal and topological aspects affect the relationship between R₀ and Ω, but in different ways. Introduction The interaction between medical and theoretical epidemiology of infectious diseases is probably not as strong as it should. Many results in the respective fields fail to migrate to the other. -

Epidemic Models

Chapter 9 Epidemic Models 9.1 Introduction to Epidemic Models Communicable diseases such as measles, influenza, and tuberculosis are a fact of life. We will be concerned with both epidemics, which are sudden outbreaks of a disease, and endemic situations, in which a disease is always present. The AIDS epidemic, the recent SARS epidemic, recurring influenza pandemics, and outbursts of diseases such as the Ebola virus are events of concern and interest to many peo- ple. The prevalence and effects of many diseases in less-developed countries are probably not as well known but may be of even more importance. Every year mil- lions, of people die of measles, respiratory infections, diarrhea, and other diseases that are easily treated and not considered dangerous in the Western world. Diseases such as malaria, typhus, cholera, schistosomiasis, and sleeping sickness are endemic in many parts of the world. The effects of high disease mortality on mean life span and of disease debilitation and mortality on the economy in afflicted countries are considerable. We give a brief introduction to the modeling of epidemics; more thorough de- scriptions may be found in such references as [Anderson & May (1991), Diekmann & Heesterbeek (2000)]. This chapter will describe models for epidemics, and the next chapter will deal with models for endemic situations, but we begin with some general ideas about disease transmission. The idea of invisible living creatures as agents of disease goes back at least to the writings of Aristotle (384 BC–322 BC). It developed as a theory in the sixteenth century. The existence of microorganisms was demonstrated by van Leeuwenhoek (1632–1723) with the aid of the first microscopes. -

Commentary Inducing Autoimmune Disease to Treat Cancer

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 96, pp. 5340–5342, May 1999 Commentary Inducing autoimmune disease to treat cancer Drew M. Pardoll Department of Oncology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 21205-2196 For many years, visions for development of successful immu- colleagues (6) discovered that the target for a melanoma- notherapy of cancer revolved around the induction of immune specific CD81 T cell clone grown from a melanoma patient was responses against tumor-specific ‘‘neoantigens.’’ However, as wild-type tyrosinase, a melanosomal enzyme selectively ex- demonstrated in a recent paper in the Proceedings by Overwijk pressed in melanocytes and responsible for one of the steps in et al. (1), the generation of tissue-specific autoimmune re- melanin biosynthesis. Subsequently, a number of investigators sponses represents an approach to cancer immunotherapy that found that their melanoma-specific CD81 T cells indeed is gaining momentum. Thus, a new principle in cancer therapy recognized melanocyte-specific antigens rather than melano- states that the ability to induce tissue-specific autoimmunity ma-specific antigens (7–10). Most of these antigens appear to will allow for the treatment of many important cancers. be melanosomal proteins, and a number of them, including The original focus on tumor-specific neoantigens derived tyrosinase, TRP-1, TRP-2, and gp100, are involved in melanin from a number of findings. Vaccination-challenge experiments biosynthesis. Other melanosomal proteins such as MART1y performed between carcinogen-induced murine tumor models Melan A have no known function but are nonetheless mela- typically demonstrated that autologous tumors vaccinated nocyte-specific tissue differentiation antigens. -

Clustering of Susceptible Individuals Within Households Can Drive an Outbreak: an Individual-Based Model Exploration

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2019.12.10.19014282; this version posted December 14, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . Clustering of susceptible individuals within households can drive an outbreak: an individual-based model exploration Elise Kuylen1,2,*, Lander Willem1, Jan Broeckhove3, Philippe Beutels1, and Niel Hens1,4 1Centre for Health Economics Research and Modelling Infectious Diseases (CHERMID), Vaccine and Infectious Disease Institute, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium 2Discipline Group Computer Sciences, Hasselt University, Hasselt, Belgium 3IDLab, Department of Mathematics and Computer Science, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium 4I-BioStat, Data Science Institute, Hasselt University, Hasselt, Belgium *[email protected] ABSTRACT When estimating important measures such as the herd immunity threshold, and the corresponding efforts required to eliminate measles, it is often assumed that susceptible individuals are uniformly distributed throughout populations. However, unvaccinated individuals may be clustered in a variety of ways, including by geographic location, by age, in schools, or in households. Here, we investigate to which extent different levels of within-household clustering of susceptible individuals may impact the risk and persistence of measles outbreaks. To this end, we apply an individual-based model, Stride, to a population of 600,000 individuals, using data from Flanders, Belgium. We compare realistic scenarios regarding the distribution of susceptible individuals within households in terms of their impact on epidemiological measures for outbreak risk and persistence. -

Lesson 1 Introduction to Epidemiology

Lesson 1 Introduction to Epidemiology Epidemiology is considered the basic science of public health, and with good reason. Epidemiology is: a) a quantitative basic science built on a working knowledge of probability, statistics, and sound research methods; b) a method of causal reasoning based on developing and testing hypotheses pertaining to occurrence and prevention of morbidity and mortality; and c) a tool for public health action to promote and protect the public’s health based on science, causal reasoning, and a dose of practical common sense (2). As a public health discipline, epidemiology is instilled with the spirit that epidemiologic information should be used to promote and protect the public’s health. Hence, epidemiology involves both science and public health practice. The term applied epidemiology is sometimes used to describe the application or practice of epidemiology to address public health issues. Examples of applied epidemiology include the following: • the monitoring of reports of communicable diseases in the community • the study of whether a particular dietary component influences your risk of developing cancer • evaluation of the effectiveness and impact of a cholesterol awareness program • analysis of historical trends and current data to project future public health resource needs Objectives After studying this lesson and answering the questions in the exercises, a student will be able to do the following: • Define epidemiology • Summarize the historical evolution of epidemiology • Describe the elements of a case -

Xii World Asthma, Allergy & Copd Forum

XII WORLD ASTHMA, ALLERGY & COPD FORUM Saint Petersburg, Russia June 29–July 2, 2019 SAINT PETERSBURG SAINT PROGRAM World Immunopathology XIII WORLD ASTHMA, Organization (WIPO) ALLERGY & COPD FORUM Saint-Petersburg, Russia July 2–5, 2020 General Information St. Pet The World Immunopathology Organization (WIPO) is a professional, non-profit organization. WIPO was created in December 2002, at the I World Congress on Immunopathology in Singapore. During these years, WIPO successfully organized many international congresses and regional and national meetings throughout See you in Saint Petersburg in 2020! the world all promoting basic and clinical research and giving an opportunity for exchanging ideas. WIPO is aimed at collecting and disseminating scientific information and providing training and continuous education in various fields of immunopathology. Aims and Mission Nowadays, immunopathology has become a multidisciplinary problem. The WIPO global mission is to promote through education and research activities worldwide: – basic and clinical research in experimental and clinical immunology, allergy and asthma, autoimmunity, immunodeficiency, AIDS, immunobiotechnology, – prevention and treatment of different manifestations of immunopathology—immune-associated disorders, – excellence in patient care in this very important area of medicine and to establish communication between specialists in various fields of medical science and practice. e We encourage to join WIPO national and regional societies as well as individual members—doctors -

Some Mathematical Models in Epidemiology

Preliminary Definitions and Assumptions Mathematical Models and their analysis Some Mathematical Models in Epidemiology by Peeyush Chandra Department of Mathematics and Statistics Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur, 208016 Email: [email protected] Peeyush Chandra Some Mathematical Models in Epidemiology Preliminary Definitions and Assumptions Mathematical Models and their analysis Definition (Epidemiology) It is a discipline, which deals with the study of infectious diseases in a population. It is concerned with all aspects of epidemic, e.g. spread, control, vaccination strategy etc. WHY Mathematical Models ? The aim of epidemic modeling is to understand and if possible control the spread of the disease. In this context following questions may arise: • How fast the disease spreads ? • How much of the total population is infected or will be infected ? • Control measures ! • Effects of Migration/ Environment/ Ecology, etc. • Persistence of the disease. Peeyush Chandra Some Mathematical Models in Epidemiology Preliminary Definitions and Assumptions Mathematical Models and their analysis Infectious diseases are basically of two types: Acute (Fast Infectious): • Stay for a short period (days/weeks) e.g. Influenza, Chickenpox etc. Chronic Infectious Disease: • Stay for larger period (month/year) e.g. hepatitis. In general the spread of an infectious disease depends upon: • Susceptible population, • Infective population, • The immune class, and • The mode of transmission. Peeyush Chandra Some Mathematical Models in Epidemiology Preliminary Definitions and Assumptions Mathematical Models and their analysis Assumptions We shall make some general assumptions, which are common to all the models and then look at some simple models before taking specific problems. • The disease is transmitted by contact (direct or indirect) between an infected individual and a susceptible individual. -

Foundations of Epidemiology

66221_CH01_5398.qxd 6/19/09 11:16 AM Page 1 © Jones and Bartlett Publishers, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION CHAPTER 1 Foundations of Epidemiology OBJECTIVES After completing this chapter, you will be able to: ■ Define epidemiology. ■ Define descriptive epidemiology. ■ Define analytic epidemiology. ■ Identify some activities performed in epidemiology. ■ Explain the role of epidemiology in public health practice and individual decision making. ■ Define epidemic, endemic, and pandemic. ■ Describe common source, propagated, and mixed epidemics. ■ Describe why a standard case definition and adequate levels of reporting are important in epidemiologic investigations. ■ Describe the epidemiology triangle for infectious disease. ■ Describe the advanced epidemiology triangle for chronic diseases and behavioral disorders. ■ Define the three levels of prevention used in public health and epidemiology. ■ Understand the basic vocabulary used in epidemiology. 66221_CH01_5398.qxd 6/19/09 11:16 AM Page 2 © Jones and Bartlett Publishers, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION 2 CHAPTER 1 ■ Foundations of Epidemiology In recent years, the important role of epidemiology has become increasingly recognized. Epidemiology is a core subject required in public health and health education programs; it is a study that provides information about public health problems and the causes of those problems. This information is then used to improve the health and social conditions of people. Epidemiology has a population focus in that epidemiologic investigations are concerned with the collective health of the people in a community or population under study. In contrast, a clinician is concerned for the health of an individual. The clinician focuses on treating and caring for the patient, whereas the epidemiologist focuses on iden- tifying the source or exposure of disease, disability or death, the number of persons exposed, and the potential for further spread. -

Population Dynamics of Infectious Diseases: a Discrete Time Model

ecological modelling 198 (2006) 183–194 available at www.sciencedirect.com journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ecolmodel Population dynamics of infectious diseases: A discrete time model Madan K. Oli a,∗, Meenakshi Venkataraman a, Paul A. Klein b, Lori D. Wendland c, Mary B. Brown c a Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, 110 Newins-Zeigler Hall, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611-0430, United States b Department of Pathology, Immunology, and Laboratory Medicine, College of Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32610-0275 c Department of Infectious Diseases and Pathology, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32610-0880, United States article info abstract Article history: Mathematical models of infectious diseases can provide important insight into our under- Received 23 June 2005 standing of epidemiological processes, the course of infection within a host, the transmis- Received in revised form 31 March sion dynamics in a host population, and formulation or implementation of infection control 2006 programs. We present a framework for modeling the dynamics of infectious diseases in dis- Accepted 18 April 2006 crete time, based on the theory of matrix population models. The modeling framework Published on line 14 June 2006 presented here can be used to model any infectious disease of humans or wildlife with dis- crete disease states, irrespective of the number of disease states. The model allows rigorous Keywords: estimation of important quantities, including the basic reproduction ratio of the disease Basic reproduction ratio R0 (R0) and growth rate of the population ( ), and permits quantification of the sensitivity of R0 Epidemiological model and to model parameters. -

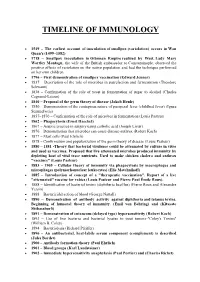

Timeline of Immunology

TIMELINE OF IMMUNOLOGY 1549 – The earliest account of inoculation of smallpox (variolation) occurs in Wan Quan's (1499–1582) 1718 – Smallpox inoculation in Ottoman Empire realized by West. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, the wife of the British ambassador to Constantinople, observed the positive effects of variolation on the native population and had the technique performed on her own children. 1796 – First demonstration of smallpox vaccination (Edward Jenner) 1837 – Description of the role of microbes in putrefaction and fermentation (Theodore Schwann) 1838 – Confirmation of the role of yeast in fermentation of sugar to alcohol (Charles Cagniard-Latour) 1840 – Proposal of the germ theory of disease (Jakob Henle) 1850 – Demonstration of the contagious nature of puerperal fever (childbed fever) (Ignaz Semmelweis) 1857–1870 – Confirmation of the role of microbes in fermentation (Louis Pasteur) 1862 – Phagocytosis (Ernst Haeckel) 1867 – Aseptic practice in surgery using carbolic acid (Joseph Lister) 1876 – Demonstration that microbes can cause disease-anthrax (Robert Koch) 1877 – Mast cells (Paul Ehrlich) 1878 – Confirmation and popularization of the germ theory of disease (Louis Pasteur) 1880 – 1881 -Theory that bacterial virulence could be attenuated by culture in vitro and used as vaccines. Proposed that live attenuated microbes produced immunity by depleting host of vital trace nutrients. Used to make chicken cholera and anthrax "vaccines" (Louis Pasteur) 1883 – 1905 – Cellular theory of immunity via phagocytosis by macrophages and microphages (polymorhonuclear leukocytes) (Elie Metchnikoff) 1885 – Introduction of concept of a "therapeutic vaccination". Report of a live "attenuated" vaccine for rabies (Louis Pasteur and Pierre Paul Émile Roux). 1888 – Identification of bacterial toxins (diphtheria bacillus) (Pierre Roux and Alexandre Yersin) 1888 – Bactericidal action of blood (George Nuttall) 1890 – Demonstration of antibody activity against diphtheria and tetanus toxins.