Introduction: Legacies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EQL Paper 20200315

EQL -- an extremely easy to learn knowledge graph query language, achieving high-speed and precise search Han Liu Shantao Liu Beijing Lemon Flower Technology Co., Ltd. 2020.3.15 Abstract: EQL , also named as Extremely Simple Query Language , can be widely used in the fields of knowledge graph, precise search, strong artificial intelligence, database, smart speaker, patent search and other fields. EQL adopts the principle of minimalism in design and pursues simplicity and easy to learn so that everyone can master it quickly. In the underlying implementation, through the use of technologies such as NLP and knowledge graph in artificial intelligence , as well as technologies in the field of big data and search engine, EQL ensure high- speed and precise information search, thereby helping users better tap into the wealth contained in data assets. EQL language and λ calculus are interconvertible, that reveals the mathematical nature of EQL language,and lays a solid foundation for rigor and logical integrity of EQL language. In essence, any declarative statement is equivalent to a spo fact statement. The mathematical abstract form of the spo fact statement is s: p: o (q1: v1, q2: v2 ..... qn: vn), s:p:o is subject:predicate:object, or entity : attribute : attribute value. (q1: v1, q2: v2 ..... qn: vn) are called modifiers to express more details, n is 0 or a natural number; any question statement is equivalent to one or more spo question statements, the basic form of each spo question statement is to replace any symbol of the spo fact statements with the ?x, for example, s: p:?x (q1: v1, q2: v2), or s: p: o (q1:?x, q2: v2, q3: v3). -

Download Moving House: Stories, Paweðłâ•I Huelle, Harcourt Brace & Co., 1995

Moving house: stories, PaweЕ‚ Huelle, Harcourt Brace & Co., 1995, 0151627312, 9780151627318, 248 pages. Stories deal with angels, devils, family disagreements, a hidden village, and a grandfather building his own submarine. DOWNLOAD HERE Moving house a novel, Katharine Moore, 1986, Business & Economics, 154 pages. You Can't Get Lost in Cape Town , ZoГ« Wicomb, 1987, Fiction, 214 pages. The South African novel of identity that "deserves a wide audience on a par with Nadine Gordimer.". The Dangerous Joy of Dr. Sex and Other True Stories , Pagan Kennedy, 2008, Literary Collections, 247 pages. Presents a collection of literary writings that feature eccentrics and visionaries intent on transforming the world according to their peculiar ambitions.. House of day, house of night , Olga Tokarczuk, Antonia Lloyd-Jones, Feb 12, 2003, Fiction, 293 pages. Richly imagined, weaving in anecdote with recipes and gossip, "House of Day, House of Night" is an epic of a small place. In Nowa Ruda, a small town in Silesia, Poland, the .... Pierwsza miЕ‚oЕ›Д‡ i inne opowiadania, PaweЕ‚ Huelle, 1996, , 251 pages. Pornografia/ Pornography , Witold Gombrowicz, 2009, Fiction, 225 pages. During the German occupation of Poland, two men who have abandoned Warsaw for the countryside occupy themselves by trying to force a tryst between two teenagers on a local farm .... The Darkest Clearing , Brian Railsback, Apr 1, 2004, Fiction, 327 pages. Equal parts intimate character study and page-turning thriller, this novel explores the extremes of both genres, combining a fascinating story with timely reflections on 21st .... Mercedes-Benz from Letters to Hrabal, PaweЕ‚ Huelle, 2005, History, 154 pages. -

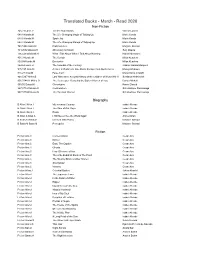

Read 2020 Book Lists

Translated Books - March - Read 2020 Non-Fiction 325.73 Luise.V Tell Me How It Ends Valeria Luiselli 648.8 Kondo.M The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up Marie Kondo 648.8 Kondo.M Spark Joy Marie Kondo 648.8 Kondo.M The Life-Changing Manga of Tidying Up Marie Kondo 741.5944 Satra.M Embroideries Marjane Satrapi 784.2092 Ozawa.S Absolutely on Music Seiji Ozawa 796.42092 Murak.H What I Talk About When I Talk About Running Haruki Murakami 801.3 Kunde.M The Curtain Milan Kundera 809.04 Kunde.M Encounter Milan Kundera 864.64 Garci.G The Scandal of the Century Gabriel Garcia Marquez 915.193 Ishik.M A River In Darkness: One Man's Escape from North Korea Masaji Ishikawa 918.27 Crist.M False Calm Maria Sonia Cristoff 940.5347 Aleks.S Last Witnesses: An Oral History of the Children of World War II Svetlana Aleksievich 956.704431 Mikha.D The Beekeeper: Rescuing the Stolen Women of Iraq Dunya Mikhail 965.05 Daoud.K Chroniques Kamel Daoud 967.57104 Mukas.S Cockroaches Scholastique Mukasonga 967.57104 Mukas.S The Barefoot Woman Scholastique Mukasonga Biography B Allen.I Allen.I My Invented Country Isabel Allende B Allen.I Allen.I The Sum of Our Days Isabel Allende B Allen.I Allen.I Paula Isabel Allende B Altan.A Altan.A I Will Never See the World Again Ahmet Altan B Khan.N Satra.M Chicken With Plums Marjane Satrapi B Satra.M Satra.M Persepolis Marjane Satrapi Fiction Fiction Aira.C Conversations Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C Dinner Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C Ema, The Captive Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C Ghosts Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C How I Became a Nun Cesar -

Creative Writing Workshops - by Marjorie H Morgan! to Be Used Alongside the Podcast

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Creative Writing Workshops - by Marjorie H Morgan! to be used alongside the podcast MT Productions 1 of 28 Marjorie H Morgan Sessions Week 1 Introduction to Creative Writing, Writer’s Toolbox and character development Week 2 Flash Fiction and short stories Week 3 Poetry - written and performance Week 4 Blogs and journaling ! ! MT Productions 2 of 28 Marjorie H Morgan Week 1 ! ! Introduction to Creative Writing, Writer’s Toolbox and character development ! ! 10 Rules of Writing 1) Read. Read. Read. 2) Write. ! Write what you know - your POV! Write interests what intrigues you! Write what you don’t know! Write - don’t be perfect, just write (the way you write) 3) Listen.! Listen to your writing! Listen to other people talking! Listen to dialogue 4) Have a story.! Protaganist! Antagonist! Build drama - suspense! Show, don’t tell 5) Edit.! Read you draft ALOUD! Do not be afraid to change what you have written 6) Share.! Constructive criticism 7) Practice.! Take/make time to write! Make it a regular habit 8) Go for a walk.! Inspiration - narrative triggers! Keep human - see people, go places! Make notes - writer’s notebook 9) Finish what you are writing. 10) Be honest. Tell the Truth.! ! MT Productions 3 of 28 Marjorie H Morgan What’s in the Writer’s Toolbox? Toolbox! Vocabulary Grammar (dialogue)! Words / sentences / paragraphs Experience Observation Plots Settings Characterisation - internal/external worlds Style ! ! MT Productions 4 of 28 Marjorie H Morgan In these pandemic times, and beyond, it’s useful to remember -

English 200, Microfiction: an Introduction to the Very Short Story

Dr William Nelles [email protected] English 200, Microfiction: An Introduction to the Very Short Story Description Narrative fiction is traditionally divided into two major categories, the novel and the short story, with the transitional category of the novella serving to cover very long short stories or very short novels. But over the last thirty years or so there has been a publishing boom in what some critics consider a new genre of the very short story, variously labeled as “microfiction,” “flash fiction,” or “sudden fiction.” This new form seems to be an indirect descendant of such ancient literary types as the parable, fable, fabliau, and myth, on the one hand, and a relative of such nonliterary modern forms as the pop song, music video, TV commercial, cartoon, and comic strip, on the other. We will read, discuss, and write about a series of critical essays on the topic and a large number of very short stories (most of them under one page in length) to analyze their characteristics and to consider their relationship to some of these other very short forms. Texts Steve Moss, ed. The World’s Shortest Stories (0762403004) Steve Moss and John M. Daniel, eds. World's Shortest Stories of Love and Death (0762406984) Jerome Stern, ed. Micro Fiction: An Anthology of Really Short Stories (0393314328) The texts are available from the UMD campus bookstore, but can usually be found even cheaper at online stores. Please use the ISBN numbers to be sure you’re getting the right books. We will also be reading a series of critical essays on microfiction: these will be made available online through the course site. -

Sudden Flash Youth : 65 Short-Short Stories / Edited by Christine Perkins- Hazuka, Tom Hazuka, and Mark Budman

F l a S h S u d d e n Y o u t h 65 Short-Short Stories e d i t e d b Y Christine Perkins-hazuka, tom hazuka, and Mark budman a Karen and Michael braziller book P e r S e a b o o ks / n e w Y o r K Compilation copyright © 2011 by Christine Perkins-hazuka, tom hazuka, and Mark budman For copyright information for individual stories, please see acknowledgments on pages 207–211. all rights reserved. no part of this publication may be reproduced or trans- mitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, digital, electronic, or any information storage and retrieval system without prior permission in writing from the publisher. requests for permission to reprint or to make copies, and for any other infor- mation should be addressed to the publisher: Persea books, inc. 277 broadway new York, new York 10007 library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data Sudden flash youth : 65 short-short stories / edited by Christine Perkins- hazuka, tom hazuka, and Mark budman. -- 1st ed. p. cm. iSbn 978-0-89255-371-6 (alk. paper) 1. Short stories, american. i. Perkins-hazuka, Christine. ii. hazuka, tom. iii. budman, Mark. PS648.S5S84 2011 813.008’035235—dc23 011021284 designed by rita lascaro Manufactured in the united States of america First edition Contents editors’ note __ ix Tamazunchale robert ShaPard__ 3 Chalk Meg KearneY__ 6 Twins PaMela Painter__ 9 First Virtual Kathleen o’donnell__ 10 Heartland daPhne beal__ 14 Confession Stuart DybeK__ 18 Sleeping Katharine weber__ 19 1951 riChard bausch__ 21 Little BrothertM bruCe holland rogerS__ 24 Currents hannah bottomy Voskuil__ 28 After bill KonigSberg__ 30 Accident daVe eggerS__ 33 Homeschool Insider: The Fighting Pterodactyls ron CarlSon__ 35 Forgotten anne Mazer__ 38 After He Left Matt hlinaK__ 42 The Flowers aliCe walKer__ 43 Homeward Bound toM hazuKa__ 45 A Car Pia z. -

Udal Liburutegi Nagusia - Biblioteca Municipal Central

Udal Liburutegi Nagusia - Biblioteca Municipal Central Euskaraz. Iñigo Aranbarri (dinamatzailea) Ekitaldi aretoa / Sala de Actividades (San Jerónimo) 19:30 1 2 5 3 0 n I Irailak 17 Septiembre Deklaratzekorik ez / Beñat Sarasola Urriak 8 Octubre Hezurren erretura / Miren Agur Meabe Azaroak 5 Noviembre Esnearen kolorekoa / Nall Leyshon Abenduak 3 Diciembre Basa / Miren Amuriza Urtarrilak 14 Enero Babilonia / Joan Mari Irigoien Otsailak 11 Febrero Trikua esnatu da : euskaratik feminismora eta feminismotik euskarara / Lorea Agirre Dorronsoro Martxoak 10 Marzo Aldibereko / Ingeborg Bachmann Apirilak 7 Abril Urtaroak eta zeinuak / Jon Gerediaga Maiatzak 12 Mayo Miñan / Amets Arzallus www.donostiakultura.eus/liburutegiak @DK_Liburutegiak [email protected] En castellano. Amaia García (dinamizadora) Ekitaldi aretoa / Sala de Actividades (San Jerónimo) 19:30 Irailak 17 Septiembre El quinto hijo / Doris Lessing Urriak 22 Octubre Gloria / Vladimir Nabokov Azaroak 26 Noviembre Yo voy, tú vas, él va / Jenny Erpenbeck Abenduak 17 Diciembre Ordesa / Manuel Vilas (escritor invitado) Urtarrilak 28 Enero El rumor del oleaje / Yukio Mishima Otsailak 25 Febrero Persuasión / Jane Austen Martxoak 31 Marzo La campana de cristal / Sylvia Plath Apirilak 28 Abril Mañana tendremos otros nombres / Patricio Pron (escritor invitado) 1 2 Maiatzak 26 Mayo El desierto de los tártaros / Dino Buzzati 5 3 0 n I Ekainak 30 Junio Mejor hoy que mañana / Nadine Gordimer www.donostiakultura.eus/liburutegiak @DK_Liburutegiak [email protected] In english. Slawka Grabowska (coordinator) Ekitaldi aretoa / Sala de Actividades (San Jerónimo) 18:45 Irailak 16 Septiembre The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie / Muriel Spark Urriak 14 Octubre In a Free State / V.S. Naipaul Azaroak 11 Noviembre Lolly Willowes / Sylvia Townsend Warner Abenduak 9 Diciembre Pygmalion / George Bernard Shaw Urtarrilak 14 Enero The Man in the High Castle / Philip K. -

SYLLABUS HUMS 619-01: August 6-10 Flash Fiction/Prose Poetry: An

SYLLABUS HUMS 619-01: August 6-10 Flash Fiction/Prose Poetry: An Immersive Reading and Writing Workshop Instructor: Martine Bellen Email: [email protected] Room: Downey Hall 100 Though flash fiction (short short stories) and prose poetry have been known to rub elbows from time to time, readers of flash fiction will tend to discuss texts in terms of character, plot, conflict, while readers of prose poetry will deliberate about sound devices, figurative language, and rhythm. In this workshop, close readings of these two genres will be conducted, investigating, side by side, how they work as a means to explore fresh avenues of entry into fiction and poetry, using the other as a springboard to more deeply navigate each genre. In the reading component of the workshop, we will learn how ordinary prose can be heightened to create extraordinary word environments for both fiction and poetry and in the creative writing component, we will apply to our writing the techniques identified in discussions about texts. All participants will be expected to write both flash fiction and prose poetry and to workshop both genres. Texts (can be found at bookstore or ordered online): 1. David Lehman (editor), GREAT AMERICAN PROSE POEMS (Scribner) 2. James Thomas, Denise Thomas & Tom Hazuka (editors), FLASH FICTION: 72 VERY SHORT STORIES (W.W. Norton & Company) 3. THE COLLECTED WRITINGS OF JOE BRAINARD (The Library of America) 4. Harryette Mullen, SLEEPING WITH THE DICTIONARY (University of California Press) 5. Barbara Henning, LOOKING UP HARRYETTE MULLEN: INTERVIEWS ON SLEEPING WITH THE DICTIONARY AND OTHER WORKS (Belladonna) Oral presentations: prepare a 15-minute oral presentation on the author (and his or her book/prose) that you’re assigned. -

MFA in Writing Projected Schedule Spring I 21 (Jan-March)

MFA in Writing Projected Schedule Spring 2021-Spring 2022 NOTE: This schedule is for tentative planning purposes only and is subject to change. Click on each course number linked below to view course description, class type, and textbook info. Course numbers that do not have links below will be listed on the Curriculum page when they are offered. The bold portion of each course title is the portion that appears in the student portal; refer to the course number, instructor name, and term dates when self-enrolling in classes. Spring I 21 (Jan-March) MARY ANDERSON: IMF 53713 Selected Emphases in Fiction VI: American Women Short-Story Masters I RON AUSTIN: IMF 53702 Selected Emphases in Fiction: Magical Realism Lit & Workshop CHRISTOPHER CANDICE: ON-CAMPUS CLASS: IMF 55100 Fiction Craft Foundations WM ANTHONY CONNOLLY: IMF 52306 Focused Nonfiction Workshop: Lyric & Personal Essays TONY D’SOUZA: IMF 52211 Focused Fiction Workshop I IMF 53707 Selected Emphases in Fiction: African American Literature CHARLENE ENGLEKING: IMF 54407 Genre Fiction Workshop: Sci-Fi Lit + Workshop: Neil Gaiman - Charlene Engleking PATRICIA FEENEY: IMF 52318 Focused Nonfiction Workshop IX: Writing About Trauma: Putting the Hard Stuff on Paper (Craft/Literature) LISA HAAG: IMF 56200 Classic Foundational Literature: Creative Nonfiction IMF 52301 Focused Nonfiction Workshop: Flash Nonfiction KENDRA HAYDEN: IMF 53716 Selected Emphases in Fiction IX: Latin American Literature II DAVID HOLLINGSWORTH: IMF 51602 Fiction Genres: Fiction Craft & Workshop EVE JONES: IMF 52104 -

Flash Fiction

Flash Fiction An introduction to very short stories! Contents Introducing Flash Fiction 3 ‘Something to Tell You’ by Aidan Chambers 4 ‘Chocolate’ by Kevin Crossley-Holland 5 ‘My Problem is I Don’t Know When to Stop’ by Morris Gleitzman 6 ‘Making Friends’ by Chris Higgins 7 ‘Routine’ by Calum Kerr 8 ‘The Monster’ by Jon Mayhew 9 ‘An Easy Cure for Insomnia’ by Pratima Mitchell 10 ‘Flower of the Fern’ by Jan Pienkowski 11 ‘The Dragon’ by Angie Sage 12 More Flash Fiction! 13 Writing your own Flash Fiction 14 Flash Fiction Mind Map 15 2 Introducing Flash Fiction Welcome to the Beyond Booked Up Flash Fiction collection! So what is Flash Fiction? Put simply, it’s a very short story. It’s normally between 300 and 500 words in length, but it could be as short as 50 words! Because it’s so short, it normally captures one single event, offering just a glimpse of a moment in time. This collection is designed to give you a peek into the world of Flash Fiction. The stories we’ve chosen offer something for everyone – from the laugh-out- loud humour of ‘Chocolate’ to the intriguing science fiction of ‘Routine’. The one thing these stories have in common is that they’re short – less than 500 words each – so you can read them in a flash! We hope that after reading the stories you’ll be feeling inspired to write one of your own. At the back of this booklet we’ve included some writing tips from Calum Kerr, author and founder of National Flash Fiction Day. -

Must Do Must

Books! Books! Books! There is no end to knowledge. All you need to do is flip through the pages to get that extra dose of BOOKS infotainment. So simply read on... 03 SELMA LAGERLOF DORIS LESSING NOBEL NOD FOR: Telling stories rooted NOBEL NOD FOR: Writing about how in the sagas of her homeland and why we live The Swedish writer was the first woman In 2007, the British-Zimbabwean author to win the award in became the oldest person 1909. Besides writ- to win the Nobel at ing, she pursued 88. Her work was women’s issues mostly centred and helped Jewish writer Nelly Sachs around political, feminist issues; and escape Nazi persecution in WWII. race relations in Zimbabwe. READ SHIKASTA: Published in 1979, the READ THE WONDERFUL ADVENTURES OF science fiction novel is about the his- NILS: The 1906 story follows the life tory of a planet, Shikasta, under the of a boy named Nils Holgersson. influence of three galactic empires. SVETLANA ALEXIEVICH TONI MORRISON NOBEL NOD FOR: Giving voice to the NOBEL NOD FOR: Depicting the historical post-Soviet individual role of African-American women in society The investigative journalist was the first Awarded the Nobel in 1993, the laure- woman from Belarus to receive the ate’s best-selling work explored award in 2015. Her books depict life black identity in America, and during, and after, the Soviet Union in particular, offered an idea through the experience of indi- of what it means to live in a vidual – and was presented as a black woman’s body. -

Hint Fiction: an Anthology of Stories in 25 Words Or Fewer / Edited by Robert Swartwood.—1St Ed

Further praise for Hint Fiction “The stories in Robert Swartwood’s Hint Fiction have some serious velocity. Some explode, some needle, some bleed, and some give the reader room to dream. They’re fun and addictive, like puzzles or haiku or candy. I’ve finished mine but I want more.” —Stewart O’Nan *hint fiction hint fiction An Anthology of Stories in 25 Words or Fewer Edited by Robert Swartwood W. W. NORTON & COMPANY * New York London “Before Perseus” by Ben White. First published in PicFic, October 30, 2009. “Claim” by Gwendolyn Joyce Mintz. First published in Sexy Stranger, February 2006, issue 4. “Corrections & Clarifications” by Robert Swartwood. First published in elimae, October 2008. “Found Wedged in the Side of a Desk Drawer in Paris, France, 23 December 1989” by Nick Mamatas. First published in Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet, May 2003, issue 12. “Free Enterprise” by Kelly Spitzer. First published in elimae, December 2007. “The End or the Beginning” by James Frey © Big Jim Industries. “The Mall” by Robley Wilson © Blue Garage Co. “The Widow’s First Year” by Joyce Carol Oates © Ontario Review, Inc. Copyright © 2011 by Robert Swartwood Individual contributions copyright © by the contributor All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hint fiction: an anthology of stories in 25 words or fewer / edited by Robert Swartwood.—1st ed. p. cm. ISBN: 978-0-393-34022-8 1. Short stories, American. 2. American fiction—21st century. I. Swartwood, Robert. PS648.S5H56 2010 813'.010806—dc22 2010016056 W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y.