The Bayeux Tapestry: Norman and English Perspectives Intertwined

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bayeux Tapestry Writing Assignment You Do Not Have to Be A

Bayeux Tapestry Writing Assignment You do not have to be a needlepoint enthusiast to appreciate the magnificent Bayeux Tapestry, which chronicles the events leading up to the conquest of England by Duke William of Normandy in the year 1066. Technically speaking it is not a tapestry at all – but an embroidery, stitched with wool on a linen background by a team of needle workers. But the interesting question is: was it made just to celebrate a great victory? To answer this question you have to consider the political situation at the time. Duke William claimed that the King, Edward the Confessor, had promised him the throne of England. However this event had not been properly witnessed or recorded. He also claimed that Harold, the future King of England, had previously sworn allegiance to him. But Harold had been imprisoned in France at that time, and his actions could have been misunderstood. On Edward’s death, William of Normandy had expected to ascend the English throne. But instead Harold disputed his claims, insisting that the Kingdom had been bequeathed to him by the dying monarch, and was duly crowned King. William replied to this by invading England, defeating the English army and killing King Harold at the Battle of Hastings. Now the new King William had to ensure that history told the story his way. What better way to achieve this than with a huge 230 feet long tapestry – a priceless work of art, which would be preserved for centuries, and confirm his right, and that of his successors, to the throne of England. -

Cremation Grave Textiles Examples from Vendel Upper Class in the Vendel and Viking Periods

Journal of Nordic Archaeological Science 13, pp. 59–74 (2002) Cremation grave textiles Examples from Vendel upper class in the Vendel and Viking Periods Anita Malmius Few are aware of the fact that organic material such as textiles and leather can survive in cremation graves. Even fewer are aware that charred textile fragments contain almost the same information as unburnt prehistoric textiles. This fact provides the opportunity for comparing textiles from different groups in society, for studying textile development, and for gaining access to a much greater textile material based on the numerous crema- tion graves. In this article the outfits of the men buried in the cremation graves in “Vendla’s Mound”, dated to the Vendel and Viking Periods, are compared with those buried in the contemporaneous boat-graves in Vendel. Introduction strong materialistic attitudes to death and life thereafter. The In an overview of Scandinavian textile- and leatherworking, buried person has been provided with a full set of equipment Eva Andersson (1995: 16) observes that the textile craft for the after-life. Thanks to the custom of equipping the tends to be mentioned only in passing in the archaeological dead with rich grave-goods, we can today obtain insights literature and research discussions, and that dress is primar- into some aspects of the culture of buried persons. But only ily seen as a complement to buckles and other ornaments. certain categories of objects have been laid down in the The reason for this would seem to be ‘the shortage of finds graves – already their contempories made choices as to what and other evidence’, but also, ‘poor knowledge of what has was at the time considered suitable and representative. -

Anglo- Saxon England and the Norman Conquest, 1060-1066

1.1 Anglo- Saxon society Key topic 1: Anglo- Saxon England and 1.2 The last years of Edward the Confessor and the succession crisis the Norman Conquest, 1060-1066 1.3 The rival claimants for the throne 1.4 The Norman invasion The first key topic is focused on the final years of Anglo-Saxon England, covering its political, social and economic make-up, as well as the dramatic events of 1066. While the popular view is often of a barbarous Dark-Ages kingdom, students should recognise that in reality Anglo-Saxon England was prosperous and well governed. They should understand that society was characterised by a hierarchical system of government and they should appreciate the influence of the Church. They should also be aware that while Edward the Confessor was pious and respected, real power in the 1060s lay with the Godwin family and in particular Earl Harold of Wessex. Students should understand events leading up to the death of Edward the Confessor in 1066: Harold Godwinson’s succession as Earl of Wessex on his father’s death in 1053 inheriting the richest earldom in England; his embassy to Normandy and the claims of disputed Norman sources that he pledged allegiance to Duke William; his exiling of his brother Tostig, removing a rival to the throne. Harold’s powerful rival claimants – William of Normandy, Harald Hardrada and Edgar – and their motives should also be covered. Students should understand the range of causes of Harold’s eventual defeat, including the superior generalship of his opponent, Duke William of Normandy, the respective quality of the two armies and Harold’s own mistakes. -

Virginia Theological Seminary Gothic France: 21-31 May 2021

Virginia Theological Seminary Gothic France: 21-31 May 2021 SAMPLE OF PROGRAM* Day 1: Friday, May 21, 2021 Arrival in Paris on your own Group Welcome Dinner in a restaurant Lodging in a 4 * boutique hotel in the 5th or 6th arrondissement of Paris (Hotel des Saint-Pères or similar) Day 2: Saturday May 22, 2021 Meet your private tour bus and 2 guides at your hotel for a guided day in Paris. Guided visit of the church of St Pierre de Montmartre, one of the oldest extant churches in Paris, and the Sacré Coeur Basilica with its mosaic of Christ in Glory. Lunch on your own in historic Montmartre After lunch, meet your tour bus for a guided visit of the St Denis Basilica to learn about the birth of Gothic architecture Return to the hotel at the end of the day. Dinner on your own Lodging in a 4 * boutique hotel in the 5th or 6th arrondissement of Paris (Hotel des Saint-Pères or similar) Day 3: Sunday, May 23, 2021 Meet your private tour bus and your 2 guides in front of your hotel for a day trip to Chartres. Guided tour of Notre Dame de Chartres Cathedral, a unique example of early gothic architecture, th and its 13 century Labyrinth Group Lunch in a restaurant Free time to explore the town of Chartres Return to Paris with your tour bus at the end of the day Dinner on your own Lodging in a 4 * boutique hotel in the 5th or 6th arrondissement of Paris (Hotel des Saint-Pères or similar) Day 4: Monday, May 24, 2021 Meet your 2 guides at your hotel for a guided day in Paris (transport pass provided) Guided visit of Notre Dame Cathedral (the exterior), an iconic masterpiece of Gothic architecture, ravaged by fire in April 2019. -

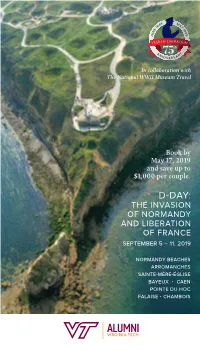

2019 Flagship Vatech Sept5.Indd

In collaboration with The National WWII Museum Travel Book by May 17, 2019 and save up to $1,000 per couple. D-DAY: THE INVASION OF NORMANDY AND LIBERATION OF FRANCE SEPTEMBER 5 – 11, 2019 NORMANDY BEACHES ARROMANCHES SAINTE-MÈRE-ÉGLISE BAYEUX • CAEN POINTE DU HOC FALAISE • CHAMBOIS NORMANDY CHANGES YOU FOREVER Dear Alumni and Friends, Nothing can match learning about the Normandy landings as you visit the ery places where these events unfolded and hear the stories of those who fought there. The story of D-Day and the Allied invasion of Normandy have been at the heart of The National WWII Museum’s mission since they opened their doors as The National D-Day Museum on June 6, 2000, the 56th Anniversary of D-Day. Since then, the Museum in New Orleans has expanded to cover the entire American experience in World War II. The foundation of this institution started with the telling of the American experience on D-Day, and the Normandy travel program is still held in special regard – and is considered to be the very best battlefield tour on the market. Drawing on the historical expertise and extensive archival collection, the Museum’s D-Day tour takes visitors back to June 6, 1944, through a memorable journey from Pegasus Bridge and Sainte-Mère-Église to Omaha Beach and Pointe du Hoc. Along the way, you’ll learn the timeless stories of those who sacrificed everything to pull-off the largest amphibious attack in history, and ultimately secured the freedom we enjoy today. Led by local battlefield guides who are experts in the field, this Normandy travel program offers an exclusive experience that incorporates pieces from the Museum’s oral history and artifact collections into presentations that truly bring history to life. -

The Bayeux Tapestry

The Bayeux Tapestry The Bayeux Tapestry A Critically Annotated Bibliography John F. Szabo Nicholas E. Kuefler ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London Published by Rowman & Littlefield A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB Copyright © 2015 by John F. Szabo and Nicholas E. Kuefler All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Szabo, John F., 1968– The Bayeux Tapestry : a critically annotated bibliography / John F. Szabo, Nicholas E. Kuefler. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4422-5155-7 (cloth : alk. paper) – ISBN 978-1-4422-5156-4 (ebook) 1. Bayeux tapestry–Bibliography. 2. Great Britain–History–William I, 1066–1087– Bibliography. 3. Hastings, Battle of, England, 1066, in art–Bibliography. I. Kuefler, Nicholas E. II. Title. Z7914.T3S93 2015 [NK3049.B3] 016.74644’204330942–dc23 2015005537 ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed -

2018 | 2 Éric Bournazel, Mutations

2018 | 2 Éric Bournazel, Mutations. Recueil d’articles d’histoire du Mittelalter – Moyen Âge (500– droit, Paris (Éditions Panthéon-Assas) 2017, 530 p., 1 ill., 1500) ISBN 979-10-90429-96-3, EUR 35,00. DOI: 10.11588/frrec.2018.2.48295 rezensiert von | compte rendu rédigé par Patrick Demouy, Reims Seite | page 1 Le titre de ce recueil fait référence au grand livre qu’Éric Bournazel a publié avec Jean-Pierre Poly en 1980, »La mutation féodale (Xe–XIIe siècles)«. Traduit en espagnol, italien et anglais, il est devenu un classique réédité et a alimenté les débats historiographiques. Ceux-ci ne sont pas relancés. Éric Bournazel, qui s’est affirmé comme un spécialiste des premiers Capétiens et de la féodalité, nous offre un florilège d’histoire institutionnelle et juridique, sans s’interdire des réflexions anthropologiques et des excursions loin du domaine qui est a priori le sien, signe d’une curiosité toujours en éveil. On en jugera par les titres des cinq sections regroupant 29 articles: »Les cercles du pouvoir«; »Jus et Ars«; »Imaginaires«,»idées«, idéologies«; »Le gouvernement des femmes«; »Échappées sportives«. Le fil conducteur de la première partie est le processus de récupération de la féodalité par la royauté. Au cours du XIIe siècle se développe une royauté suzeraine qui domine les hommes parce qu’elle domine les fiefs. D’où le concept de mouvance, ce rapport immuable entre les terres qui entraîne la chaîne des hommages. Suger utilise le terme de fief pour définir les principautés et les intégrer dans une pyramide au sommet de laquelle se trouve le roi, ou plutôt la Couronne, une abstraction distincte de la personne physique et mortelle du souverain, un concept qui a pris forme pendant l’absence de Louis VII, parti à la croisade (1147–1149). -

Gale Owen-Crocker (Ed.), the Bayeux Tapestry. Collected Papers, Aldershot, Hampshire (Ashgate Publishing) 2012, 374 P

Francia-Recensio 2013/1 Mittelalter – Moyen Âge (500–1500) Gale Owen-Crocker (ed.), The Bayeux Tapestry. Collected Papers, Aldershot, Hampshire (Ashgate Publishing) 2012, 374 p. (Variorum Collected Studies Series, CS1016), ISBN 978-1-4094-4663-7, GBP 100,00. rezensiert von/compte rendu rédigé par George Beech, Kalamazoo, MI Scholarly interest in the Bayeux Tapestry has heightened to a remarkable degree in recent years with an increased outpouring of books and articles on the subject. Gale Owen-Crocker has contributed to this perhaps more than anyone else and her publications have made her an outstanding authority on the subject. And the fact that all but three of the seventeen articles published in this collection date from the past ten years shows the degree to which her fascination with the tapestry is alive and active today. Since her own specialty has been the history of textiles and dress one might expect that these articles would deal mainly with the kinds of materials used in the tapestry, the system of stitching, and the like. But this is not so. Although she does indeed treat these questions she also approaches the tapestry from a number of other perspectives. After an eight page introduction to the whole collection the author groups the first three articles under the heading of »Textile«. I. »Behind the Bayeux Tapestry«, 2009. In this article she describes the first examination of the back of the tapestry in 1982–1983 which was accomplished by looking under earlier linings which had previously covered it, and the light which this shed on various aspects of its production – questions of color, type of stitching used, and later repairs. -

Sett Decisions

TRANSCRIPT Sett Decisions Before we begin weaving cloth, there is a bit of crucial information that we need that determines the feel and the function of the fabric, and that is sett. Sett is to weaving what gauge is to knitting. In knitting, you can take a yarn, say like a fingering weight yarn, and you can knit it on tiny, skinny needles to produce tiny, little stitches that will produce a very tight, firm fabric. That might be suitable for something like socks, like I knit my socks on 2.25 millimeter needles and I make a fabric that’s so firm and stiff that it can stand up like cardboard. You want that because that kind of fabric that is firm and stuff affords a certain kind of durability that you want for your socks. You may not want that kind of durability for any other garment that you’re gonna be wearing. So you can take that same fingering weight yarn and then knit it on much larger size needles and produce a larger stitch which then produces a loose, draped, soft fabric that is perfect for a shawl. It’s the same idea with weaving. Sett is kind of like gauge. Think about the range of fabrics that you could create with a loom. Think about a very firm, stiff, durable, tightly woven fabric. What would that be good for? That might be good for something like upholstery fabric something that needs a lot of durability. And think about something like the cloth that you wear in your shirt. -

Dark Age Tablet Weaving

Dark Age Tablet Weaving for Viking and Anglo-Saxon re-enactors 1 Introduction Tablet weaving, also known as card weaving, is a method of using square tablets with holes in the corners to weave narrow decorative bands made of wool, linen or silk threads. Tablet weaving was widespread in Europe and Britain in the first millenium AD and is an excellent craft for historical re-enactors as it is portable, interesting, little known nowadays and you can make beautiful bands to decorate your outfit. However, creating replicas of Dark Age bands is challenging. Many of the surviving historic bands are difficult to weave, and so most re-enactors either buy in tablet-weaving or weave simplified bands, and may use patterns and techniques that aren't appropriate to the Dark Ages. The aim of this document is to describe the characteristic styles and methods of Dark Age tablet- weaving. There is also information about materials, equipment and tablet-weaving techniques. Perhaps the most striking theme of the historic bands is inventiveness, and the advantage of the historic techniques is that they allow the weaver to create a far wider range of patterns than the modern methods, which were mostly developed in the 19th and 20th centuries as tablet-weaving was 'rediscovered' in Europe1. This document isn't exhaustive, and I recommend that the interested reader explore further patterns and techniques. There are many good patterns available online. Just remember, as I once read on the internet, the first instruction in tablet weaving is “remove the cat”. Please contact me with any comments or corrections. -

Re-Embroidering the Bayeux Tapestry in Film and Media: the Flip Side of History in Opening and End Title Sequences

Exemplaria Medieval, Early Modern, Theory ISSN: 1041-2573 (Print) 1753-3074 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/yexm20 Re-embroidering the Bayeux Tapestry in Film and Media: The Flip Side of History in Opening and End Title Sequences Richard Burt To cite this article: Richard Burt (2007) Re-embroidering the Bayeux Tapestry in Film and Media: The Flip Side of History in Opening and End Title Sequences, Exemplaria, 19:2, 327-350, DOI: 10.1179/175330707X212895 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1179/175330707X212895 Published online: 18 Jul 2013. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 148 View related articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=yexm20 EXEMPLARIA, VOL. 19, NO. 2, SUMMER 2007, 327 – 350 Re-embroidering the Bayeux Tapestry in Film and Media: The Flip Side of History in Opening and End Title Sequences RICHARD BURT University of Florida This essay explores homologies between the Tapestry and cinema, focusing on the opening title sequences of several fi lms that cite the Bayeux Tapestry, including The Vikings; Robin Hood, Prince of Thieves; Bedknobs and Broomsticks; Blackadder; and La Chanson de Roland. The cinematic adaptation of a medieval artifact such as the Bayeux Tapestry suggests that history, whether located in the archive, museum, or movie medievalism, always has a more or less obscure and parodic fl ip side, and that history, written or cinematic, tells a narrative disturbed by uncanny hauntings -

What Is History?

Year 7: Unit 1 – What is History? Timeline KEY TERMS The Romans invade England and begin their Someone’s view of an event. These points of view can be different depending upon 43 AD Interpretation 350 year rule. your experiences or situation. Sources are pieces of information that help historians to learn about the past. For 793 The Vikings first invade England. Source example, letters, diaries, photographs. They were made at the time. 1066 William of Normandy conquers England. Chronology This is the arrangement of dates or events in time order. 1215 The Magna Carta is created. BC means ‘Before Christ’ and refers to the years before 1AD. Also known as BCE BC The Black Death reaches England and kills which stands for ‘Before Common Era’. 1348 one-third of the population. AD means ‘Anno Domini’ which is Latin for ‘in the year of our Lord’. This refers to the AD Henry VIII begins to break away from the years after 1AD. 1533 Catholic Church and starts the Church of England. Decade A decade is a period of ten years in time. The first time Britain set up control in Century A century is a period of one-hundred years in time. 1607 another country (Jamestown in America). The Medieval period is also known as the ‘Middle Ages’. This was a period between Medieval This started the British Empire. the 6th century to the 15th century. 1914- The First World War. This refers to a source which was made at the time of an event. For example, a diary Primary Source 1918 written by a soldier during the First World War.