Verdi's High C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

Jenish Ysmanov Tenor

AIMARTISTS JENISH YSMANOV TENOR The tenor Jenish Ysmanov studied at the Kyrgyz National Conservatory in his home-town of Bishkek. Subsequently he participated in the Placido Domingo Academy in Valencia in Italy. He made his German debut in 2018 as Rodolfo (La bohème) at the Immling Festival, where he returned to in 2019 as Don Ottavio (Don Giovanni). In February 2020 he made his role and house debut as Rodolfo (Luisa Miller) at the Opera Ljubljana. He has already performed on international stages with the role of Rodolfo (La bohème) and has appeared at numerous opera houses in Italy as Alfredo (La traviata) and Il Duca di Mantova (Rigoletto). At the Teatro Verdi in Sassari he sang in Nino Rota's La notte di un nevrastenico and I due timidi the roles of Lui and Raimondo. He also performed as Raimondo at the Teatro Malibran in Venice. In addition to opera engagements, he participated in numerous concerts, including Gala concert in the Arena di Verona 2013, Concert in honor of Enrico Caruso in St. Petersburg 2013, Gala concert in Modena under the baton of Riccardo Muti in memory of Luciano Pavarotti's 80th birthday in 2015 and Mozart’s Requiem at the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino 2016. Jenish Ysmanov has been awarded numerous international prizes, including first prize in the Shabyt 2006 International Competition in Astana (Kazakhstan) and first prize in the 2007 Bibigul Tbelnova competition in Almaty (Kazakhstan). In 2008 he won the International Rimsky Korsakov Competition St. Petersburg, the first prize in the International Luciano Pavarotti Competition in St. -

She Graduates in Singing at the Conservatory of Her City

Nana Miriani Born in Tbilisi (Georgia), she graduates in singing at the Conservatory of her city. In Italy she attended the Chigiana Academy and the Course of Training and Improvement of the Academy of Singing "Arturo Toscanini" in Parma, under the guidance of Maestro Tenor Carlo Bergonzi, obtaining certificates of merit and scholarships. In 2000-2001 she attended the Specialization Course of Vocal Interpretation "Verdi Opera Studio", "Foundation Verdi Festival" at the Theatre Regio in Parma, under the guidance of Soprano Renata Scotto. She made her debut in 1998 inBusseto, playing the role of Abigaille in Nabucco by G. Verdi, conducted by Maestro Romano Gandolfi, with the Symphony Orchestra of Emilia Romagna "Arturo Toscanini" and Chorus of the Theatre Regio of Parma, in the presence of the President of the French Republic. In 2001, she sang in the Festival "Radio France", for the Opera Berlioz in Montpellier, in Cavalleria Rusticana by D. Monleone and in Resurrezione by F. Alfano, conducted by Maestro Friedemann Layer, with CD recording. During her career she played the roles of: Tosca in Tosca by G. Puccini, engaged at the Teatro alla Scala in Milan, conducted by Maestro Lorin Maazel and directed by Luca Ronconi (2006), and at the National Theatre in Bratislava (2002, 2003, 2004) Abigaille in Nabucco by G. Verdi, at the Teatro Lirico in Cagliari, conducted by Maestro Antonello Allemandi and directed by Daniele Abbado, at Theatre Bielefeld, Germany (2006), at the Wielki Theatre in Poznan, Poland (2006), at the State Opera Z. Paliashvili of Tbilisi, alongside bass Paata Burchuladze and baritone Lado Ataneli (2009), at the Festival Steinbruch Rohrdorf of Munich, Germany (2009), at the National State Opera A. -

Michael Schade at a Special Release of His New Hyperion Recording “Of Ladies and Love...”

th La Scena Musicale cene English Canada Special Edition September - October 2002 Issue 01 Classical Music & Jazz Season Previews & Calendar Southern Ontario & Western Canada MichaelPerpetual Schade Motion Canada Post Publications Mail Sales Agreement n˚. 40025257 FREE TMS 1-01/colorpages 9/3/02 4:16 PM Page 2 Meet Michael Schade At a Special Release of his new Hyperion recording “Of ladies and love...” Thursday Sept.26 At L’Atelier Grigorian Toronto 70 Yorkville Ave. 5:30 - 7:30 pm Saturday Sept. 28 At L’Atelier Grigorian Oakville 210 Lakeshore Rd.E. 1:00 - 3:00 pm The World’s Finest Classical & Jazz Music Emporium L’Atelier Grigorian g Yorkville Avenue, U of T Bookstore, & Oakville GLENN GOULD A State of Wonder- The Complete Goldberg Variations (S3K 87703) The Goldberg Variations are Glenn Gould’s signature work. He recorded two versions of Bach’s great composition—once in 1955 and again in 1981. It is a testament to Gould’s genius that he could record the same piece of music twice—so differently, yet each version brilliant in its own way. Glenn Gould— A State Of Wonder brings together both of Gould’s legendary performances of The Goldberg Variations for the first time in a deluxe, digitally remastered, 3-CD set. Sony Classical celebrates the 70th anniversary of Glenn Gould's birth with a collection of limited edition CDs. This beautifully packaged collection contains the cornerstones of Gould’s career that marked him as a genius of our time. A supreme intrepreter of Bach, these recordings are an essential addition to every music collection. -

Staged Treasures

Italian opera. Staged treasures. Gaetano Donizetti, Giuseppe Verdi, Giacomo Puccini and Gioacchino Rossini © HNH International Ltd CATALOGUE # COMPOSER TITLE FEATURED ARTISTS FORMAT UPC Naxos Itxaro Mentxaka, Sondra Radvanovsky, Silvia Vázquez, Soprano / 2.110270 Arturo Chacon-Cruz, Plácido Domingo, Tenor / Roberto Accurso, DVD ALFANO, Franco Carmelo Corrado Caruso, Rodney Gilfry, Baritone / Juan Jose 7 47313 52705 2 Cyrano de Bergerac (1875–1954) Navarro Bass-baritone / Javier Franco, Nahuel di Pierro, Miguel Sola, Bass / Valencia Regional Government Choir / NBD0005 Valencian Community Orchestra / Patrick Fournillier Blu-ray 7 30099 00056 7 Silvia Dalla Benetta, Soprano / Maxim Mironov, Gheorghe Vlad, Tenor / Luca Dall’Amico, Zong Shi, Bass / Vittorio Prato, Baritone / 8.660417-18 Bianca e Gernando 2 Discs Marina Viotti, Mar Campo, Mezzo-soprano / Poznan Camerata Bach 7 30099 04177 5 Choir / Virtuosi Brunensis / Antonino Fogliani 8.550605 Favourite Soprano Arias Luba Orgonášová, Soprano / Slovak RSO / Will Humburg Disc 0 730099 560528 Maria Callas, Rina Cavallari, Gina Cigna, Rosa Ponselle, Soprano / Irene Minghini-Cattaneo, Ebe Stignani, Mezzo-soprano / Marion Telva, Contralto / Giovanni Breviario, Paolo Caroli, Mario Filippeschi, Francesco Merli, Tenor / Tancredi Pasero, 8.110325-27 Norma [3 Discs] 3 Discs Ezio Pinza, Nicola Rossi-Lemeni, Bass / Italian Broadcasting Authority Chorus and Orchestra, Turin / Milan La Scala Chorus and 0 636943 132524 Orchestra / New York Metropolitan Opera Chorus and Orchestra / BELLINI, Vincenzo Vittorio -

Sylwetki Fi I Muzyka 10/11

Sylwetki ���������������������� inaczej – Salvatore Licitra Maciej Łukasz Gołębiowski ��e wrześniu miał zaśpiewać Ernaniego w Tokio, w październiku Radamesa w Tajpej, a w listopadzie Pollione we włoskim Salerno. Już nie zaśpiewa. Kilkunastoletnia, przedwcześnie przerwana kariera mogła trwać o wiele dłużej, dając mu szansę wejścia na sam szczyt. Nie każdego młodego tenora nazywano drugim Pavarottim. Dziś obaj nie żyją, choć dzieliło ich pokolenie. 74 ������Fi i Muzyka 10/11 74-76 Licitra.indd 74 9/26/11 6:52:49 PM Sylwetki alvatore Licitra urodził się 10 sierp- bliczność od razu go pokochała. Wieści nie przyjętych przedstawień z zespołem nia 1968 roku w Bernie. Jego o pojawieniu się nowego talentu szybko La Scali. Aż w końcu otrzymał honorowe rodzina pochodziła z Sycylii, się rozeszły, a zachęcony owacjami Li- obywatelstwo Mediolanu i podpisał eks- z regionu Acate. Młodość spędził w Me- citra zgłosił się do mediolańskiej La Sca- kluzywny kontrakt z Sony. diolanie i, jak wielu tenorów przed nim, li na przesłuchanie do roli Alvara w no- Otwierając w La Scali sezon 2000/2001, wszedł do świata opery niejako przy- wej inscenizacji „Mocy przeznaczenia”. Licitra wystąpił w kontrowersyjnym padkiem i bez wielkich aspiracji. Jego Riccardo Muti docenił niezwykły głos przedstawieniu „Trubadura” przygoto- pierwszą pracą zarobkową było stanowi- oraz charyzmę debiutanta i osobiście wanym przez Mutiego. Opery tej nie sko gra&ka we włoskim wydaniu maga- podjął decyzję o jego angażu. Premiera wystawiano na deskach szacownego te- zynu „Vogue”. Coś go jednak ciągnęło do spektaklu miała miejsce w marcu 1999 atru od 22 lat, a włoski dyrygent słynie śpiewu. roku. z tego, że metodycznie i bezapelacyjnie trzyma się partytury. -

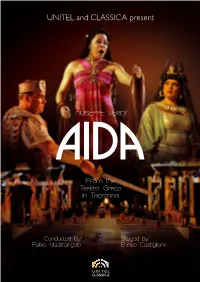

Unitel and Classica Present

Unitel and ClassiCa present GIUSEPPE VERDI AIDa From the Teatro Greco in Taormina Conducted by Staged by Fabio Mastrangelo Enrico Castiglione GIUSEPPE VERDI AIDa From the Teatro Greco in Taormina Conductor Fabio Mastrangelo rom the ancient teatro Greco in taormina, the “pearl of Orchestra Orchestra Nazionale dei the ionian sea”, comes this visually and vocally impressive Conservatori di Musica F open-air production of Giuseppe Verdi’s “aida”. evoking a “spielberg film” (Quotidiano.net), stage and video directore nrico Chorus Coro Lirico Francesco Cilea Castiglione projects video images upon the columns and ruins Chorus Master Bruno Tirotta of the 3rd-century B.C. amphitheater, creating a breathtaking Choreography Rita Colosi virtual backdrop of egyptian pillars and palms that opens onto the “nile”, in this case, the ionian sea. Complementing the aida Isabelle Kabatu virtual set is a pyramid-like monumental staircase that provides Radames Salvatore Licitra an ideal venue for the drama that unfolds. amneris Rossana Rinaldi amonasro Juan Pons Dressed in lavish egyptian-style costumes by sonia Ramfis Christophoros Stamboglis Cammarata, the performers – besides the eight soloists, a the King Antonio de’ Gobbi 100-strong chorus, a 12-member corps de ballet and 60 extras a Messenger Aldo Bruni – radiate dynamism and energy. topping the lead trio of soloists Priestess Raffaella Fraioli is the aida of isabelle Kabatu, who sings with “intensity and staged by Enrico Castiglione expressive depth” (il tempo) and who has sung this role in Berlin, Rome and the arena di Verona. an internationally acclaimed Directed by Enrico Castiglione Radames (at the Metropolitan Opera and the Bavarian state length approx. -

Publications and Translations (Selected) R

ROGER PINES – Publications and Translations (Selected) _____________________________________________________________________ Recording Companies DECCA: CD program notes for Renée Fleming’s “Guilty Pleasures” (2013), “Verismo” (2009, Grammy winner), “Four Last Songs” (2008), “Strauss Heroines” (1999), “Star-Crossed Lovers” (with Plácido Domingo 1999), and “I Want Magic!” (1998); Cecilia Bartoli’s “Sospiri” retrospective album (2010); Juan Diego Flórez’s “Bel Canto Spectacular” (2008); Jonas Kaufmann’’s “Verismo Arias” (2011), “German Arias” (2009), and “Romantic Arias” (2008); Danielle de Niese’s “Baroque Gems”(2011) and “Handel Arias” (2008); Erwin Schrott’s “Arias” (2008); Nicole Cabell’s “Soprano” (2006). DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON: program note for “Anna Netrebko at the Salzburg Festival” 3-DVD set (2014); program note for “Anna Netrebko Sings Verdi” (2013); program note and press material for “Ideale: Ben Heppner Sings Songs of Paolo Tosti” (2004); program note for re-release of Beverly Sills’s recordings of Manon (2004) and Norma (2009). EMI CLASSICS: program note for CD recital of Rachmaninoff songs by baritone Dmitri Kharitanov and pianist Leif Ove Andsnes (1999). ERATO: program note for “Wayfaring Stranger,” CD by mezzo-soprano Susanne Mentzer and guitarist Sharon Isbin (1999). RCA: program note for operatic recital by Ben Heppner (1995). SONY CLASSICS: program notes for aria recitals by soprano Nino Machaidze (2011) and tenor Vittorio Grigolo (2015, 2013, 2010); press material regarding CDs by soprano Sonya Yoncheva (2014) and tenor Salvatore Licitra (2011). VIRGIN CLASSICS: program notes for mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato’s “Diva/Divo” (2011, Grammy winner) and “ReJOYCE!” retrospective album (2014). WEST HILL RADIO ARCHIVES: program notes for “Jussi Björling – Broadcast Concerts, 1937-1960” (2010). -

The Girl of the Golden West Performer Biographies

THE GIRL OF THE GOLDEN WEST PERFORMER BIOGRAPHIES Deborah Voight (Minnie) Deborah Voigt is hailed by the worldʼs critics and audiences as todayʼs foremost dramatic soprano. The former Adler Fellow and Merola Opera Program alumna made her main stage debut in Don Carlos and has since returned to the Company in nine subsequent productions, most recently as Amelia Anckarström in Un Ballo in Maschera (2006). In addition to the role of Amelia in the 1990 production of Un Ballo in Maschera, her other performances at San Francisco Opera include Anna (Nabucco), Elisabeth (Tannhäuser), the title role of Ariadne auf Naxos, and Sieglinde (Die Walküre); these performances in La Fanciulla del West mark her role debut as Minnie. Voigt is a regular artist at the Metropolitan Opera—recent appearances there include the roles of Chrysothemis (Elektra), Senta (Der Fliegende Holländer), Isolde (Tristan und Isolde), Leonora (La Forza del Destino), the Empress (Die Frau ohne Schatten), Sieglinde, and the title roles of Tosca, Aida, Die Ägyptische Helena, and La Gioconda. She also performs regularly with Vienna State Opera (Tosca, the title roles of Salome and Ariadne auf Naxos, the Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier, Isolde, Brünnhilde in Siegfried); Paris Opera (Senta, Lady Macbeth in Macbeth); the Royal Opera, Covent Garden (Ariadne, the Empress in Die Frau ohne Schatten, and the title role of Die Ägyptische Helena); Lyric Opera of Chicago (Salome, Isolde, Sieglinde, Tosca), Barcelonaʼs Gran Teatre del Liceu (Maddalena in Andrea Chénier, the title role of La Gioconda, Isolde) and the Salzburg Festival (the title role of Die Liebe der Danae). The Illinois native was a gold medalist in the 1990 Tchaikovsky Competition and received first prize in Italyʼs Verdi Competition. -

Concerts and Master Classes June 30-July 19, 2014

Concerts and Master Classes June 30-July 19, 2014 1 About the Program In its ninth year, Westminster’s CoOPERAtive Program provides three weeks of intensive opera training for young singers. The program is presented in cooperation and consultation with professionals in the field of opera and is designed to help young singers prepare for the essential next step toward acceptance into an advanced young artist or summer apprentice program. The CoOPERAtive offers three levels of training: 1. CoOPERAtive Fellows - singers who are either current graduate students or post graduates, working toward a professional singing career. 2. CoOPERAtive Young Artists - singers who are current undergraduates in music conservatories around the country, who are preparing for graduate school. 3. CoOPERAtive Pianists - pianists who are working toward careers as coaches and conductors in opera and art song. CoOPERAtive is designed to assess the strengths of all participants, nurture their talents and assist in their skill development. Participants receive private coaching focusing on operatic style, performance techniques, dramatic presentation, language and diction, and body awareness, as well as résumé and application advice. CoOPERAtive features unique auditions in which singers are evaluated by professionals in the field of opera – advisors involved with regional opera and/or young artist programs. With their guidance, the program is customized to each singer’s needs to help improve his or her skills. Graduates of the program have been finalists in the Metropolitan Opera Council’s National Auditions and have gone on to work with opera companies throughout the United States. The public is welcome to attend master classes and concerts presented by participants at no charge. -

El Met Vuelve a Yelmo Cines the Met: Live in HD Series Triunfa En España

EL MET vuelve A YELMO CINES The Met: Live in HD series triunfa en España EL éxito de la primera temporada de retransmisiones desde el l pasado 9 de octubre metropolitan opera house de nueva york en los cines yelmo de tuvo lugar en España la primera retransmi- toda españa –THE MET: LIVE IN HD SERIES– ha animado al sión, vía satélite y en exhibidor A ofrecer durante los meses de junio Y julio una alta definición, de la temporada de verano –CON algunAS de las mejores temporada The Met: Live in HD series PRODUCCIONES DE LOS últimos AÑOS– Y A renovar su acuerdo con desde el Metropolitan Opera House el coliseo estadounidense para ofrecer, A partir del mes de Ede Nueva York. A partir de ese mo OCTUBRE, EL nuevo CURSO THE MET: LIVE IN HD 2011-12. mento y hasta el mes de mayo, 22 salas de Yelmo Cines de España de Por Belén PUEYO ciudades y provincias como Madrid, 34 ÓPERA ACTUAL LA ÓPERA DEL MET EN YELMO CINES en portada Pasquale, con Anna Netrebko; La Fanciulla del West, protagonizada por Deborah Voigt y Marcello Giordani; Nixon en China, compuesta y dirigida por John Adams; Iphigénie en Tauride, con Plácido Domingo; Capriccio, pro- tagonizada por Renée Fleming; las Metropolitan Opera / Ken HOWARD exitosas Don Carlo, Lucia di Lammer- moor, Le Comte Ory e Il Trovatore, los títulos que han sumado un mayor s e n i C número de espectadores; así como las o m l e dos primeras entregas de Der Ring des Y Nibe lungen, Das Rheingold y Die Walküre, en la nueva y espectacular Pedro Nieto, responsable de contenidos producción de Robert Lepage prota- alternativos de Yelmo Cines gonizada por un elenco de excepción −Bryn Terfel, Deborah Voigt, Jonas Kaufmann, Eva-Maria Westbroek y Stephanie Blythe, entre otros−, sin duda la apuesta más ambiciosa de una oferta que continuará el próximo curso con Siegfried y Götterdäm merung. -

Cast Change Announcement – San Diego Opera

For immediate release Tuesday, February 1, 2011 Contact: Edward Wilensky Telephone: 619.232.7636 Email: [email protected] Cast Change Announcement – San Diego Opera Emmy Award Winning Stage Director Sonja Frisell Replaces John Copley in Carmen. San Diego, CA – Emmy Award winning stage director Sonja Frisell will direct Carmen in May, replacing the originally announced director John Copley. Mr. Copley has asked to be released from this production to attend to pressing family matters in England. Sonja’s staging was last seen in San Diego for the Company’s production of Otello in 2003 with Maestro Edoardo Müller on the podium. Maestro Müller will also conduct these performances of Carmen . “John is already scheduled to return in 2012 and 2013 and I look forward to welcoming him back,” adds San Diego Opera General and Artistic Director Ian Campbell. “With Sonja, the cast has an incredibly experienced stage director who has worked both with the conductor and Salvatore Licitra who makes his Company debut with us as Don José. I’ve been a fan of Sonja’s work for a long time and look forward to seeing her treatment of this masterpiece.” Carmen opens Saturday, May 14, 2011 for four performances and was last performed by San Diego Opera in 2006. Sonja Frisell, Stage Director British Stage Director Sonja Frisell made her San Diego Opera debut directing Otello in 2003. Recent productions include Salome for Arizona Opera and a return to La Scala for L’occasione fa il ladro. Previous seasons include Don Carlo in Chicago and Washington DC, La Gioconda and La Cenerentola at La Scala, A Masked Ball in Bologna, Maometto II and Khovanschina in San Francisco, La forza del destino , Otello and The Magic Flute in Washington DC, Elena da Feltre at the Wexford Festival, Turandot in Trieste and Calgiari, Eugene Onegin with the Arizona Opera, and The Italian Girl in Algiers at Covent Garden, San Francisco and in Verona.