Twilight of the GODS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARSC Journal, Spring 1992 69 Sound Recording Reviews

SOUND RECORDING REVIEWS Chicago Symphony Orchestra: The First Hundred Years CS090/12 (12 CDs: monaural, stereo; ADD)1 Available only from the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, 220 S. Michigan Ave, Chicago, IL, for $175 plus $5 shipping and handling. The Centennial Collection-Chicago Symphony Orchestra RCA-Victor Gold Seal, GD 600206 (3 CDs; monaural, stereo, ADD and DDD). (total time 3:36:3l2). A "musical trivia" question: "Which American symphony orchestra was the first to record under its own name and conductor?" You will find the answer at the beginning of the 12-CD collection, The Chicago Symphony Orchestra: The First 100 Years, issued by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO). The date was May 1, 1916, and the conductor was Frederick Stock. 3 This is part of the orchestra's celebration of the hundredth anniversary of its founding by Theodore Thomas in 1891. Thomas is represented here, not as a conductor (he died in 1904) but as the arranger of Wagner's Triiume. But all of the other conductors and music directors are represented, as well as many guests. With one exception, the 3-CD set, The Centennial Collection: Chicago Symphony Orchestra, from RCA-Victor is drawn from the recordings that the Chicago Symphony made for that company. All were released previously, in various formats-mono and stereo, 78 rpm, 45 rpm, LPs, tapes, and CDs-as the technologies evolved. Although the present digital processing varies according to source, the sound is generally clear; the Reiner material is comparable to RCA-Victor's on-going reissues on CD of the legendary recordings produced by Richard Mohr. -

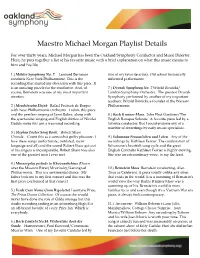

Michael Morgan Playlist

Maestro Michael Morgan Playlist Details For over thirty years, Michael Morgan has been the Oakland Symphony Conductor and Music Director. Here, he puts together a list of his favorite music with a brief explanation on what this music means to him and his life. 1.) Mahler Symphony No. 7. Leonard Bernstein two of my favorite artists. Old school historically conducts New York Philharmonic. This is the informed performance. recording that started my obsession with this piece. It is an amazing puzzle for the conductor. And, of 7.) Dvorak Symphony No. 7 Witold Rowicki/ course, Bernstein was one of my most important London Symphony Orchestra. The greatest Dvorak mentors. Symphony performed by another of my important teachers: Witold Rowicki, a founder of the Warsaw 2.) Mendelssohn Elijah. Rafael Frubeck de Burgos Philharmonic. with New Philharmonia Orchestra. I adore this piece and the peerless singing of Janet Baker, along with 8.) Bach B minor Mass. John Eliot Gardiner/The the spectacular singing and English diction of Nicolai English Baroque Soloists. A favorite piece led by a Gedda make this just a treasured recording. favorite conductor. But I could endorse any of a number of recordings by early music specialists. 3.) Stephen Foster Song Book. Robert Shaw Chorale. Count this as a somewhat guilty pleasure. I 9.) Schumann Frauenlieben und Leben. Any of the love these songs (unfortunate, outdated, racist recordings by Kathleen Ferrier. The combination of language and all) and the sound Robert Shaw got out Schumann's heartfelt song cycle and the great of his singers is incomparable. Robert Shaw was also English Contralto Kathleen Ferrier is highly moving. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

Reseña De" Giacomo Puccini: the Great Opera Collection" De Renata

Pensamiento y Cultura ISSN: 0123-0999 [email protected] Universidad de La Sabana Colombia Visbal-Sierra, Ricardo Reseña de "Giacomo Puccini: The Great Opera Collection" de Renata Tebaldi, Carlo Bergonzi, Mario del Monaco, Giulietta Simionato, et al. Pensamiento y Cultura, vol. 12, núm. 1, junio, 2009, pp. 229-231 Universidad de La Sabana Cundinamarca, Colombia Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=70111758015 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Reseñas va, sin embargo, con este encuentro el protagonista toma Giacomo Puccini: la decisión de abandonar la inmersión en el bajo mundo, en el cual no encuentra una verdadera misión en su vida, The Great Opera Collection pues comprende que la lucha violenta no transformará el mundo, sino todo lo contrario, ayudará más al caos a los (La Bohème, Tosca, Madama Butterfly, Manon Lescaut, La fan- países en vías de desarrollo. ciulla del West, Turandot, Il Trittico: Il Tabarro, Suor Angelica, Gianni Schicchi). El otro personaje con mucha más vitalidad en Buda Blues es Sebastián, un trotamundos que no se puede que- Intérpretes principales: Renata Tebaldi, Carlo Bergonzi, dar quieto en un solo lugar y busca su propia identidad Mario del Monaco, Giulietta Simionato, et al. a través de los viajes. Por eso, al inicio de la novela se en- 15 discos compactos cuentra en Kinshasa y, por amistad con Vicente, empieza a Decca 4759385 divagar sobre “La Organización” en el Congo. -

Honorary Degree Recipients 1977 – Present

Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Claire Collins Harvey, C‘37 Harry Belafonte 1977 Patricia Roberts Harris Katherine Dunham 1990 Toni Morrison 1978 Nelson Mandela Marian Anderson Marguerite Ross Barnett Ruby Dee Mattiwilda Dobbs, C‘46 1979 1991 Constance Baker Motley Miriam Makeba Sarah Sage McAlpin Audrey Forbes Manley, C‘55 Mary French Rockefeller 1980 Jesse Norman 1992 Mabel Murphy Smythe* Louis Rawls 1993 Cardiss Collins Oprah Winfrey Effie O’Neal Ellis, C‘33 Margaret Walker Alexander Dorothy I. Height 1981 Oran W. Eagleson Albert E. Manley Carol Moseley Braun 1994 Mary Brookins Ross, C‘28 Donna Shalala Shirley Chisholm Susan Taylor Eleanor Holmes Norton 1982 Elizabeth Catlett James Robinson Alice Walker* 1995 Maya Angelou Elie Wiesel Etta Moten Barnett Rita Dove Anne Cox Chambers 1983 Myrlie Evers-Williams Grace L. Hewell, C‘40 Damon Keith 1996 Sam Nunn Pinkie Gordon Lane, C‘49 Clara Stanton Jones, C‘34 Levi Watkins, Jr. Coretta Scott King Patricia Roberts Harris 1984 Jeanne Spurlock* Claire Collins Harvey, C’37 1997 Cicely Tyson Bernice Johnson Reagan, C‘70 Mary Hatwood Futrell Margaret Taylor Burroughs Charles Merrill Jewel Plummer Cobb 1985 Romae Turner Powell, C‘47 Ruth Davis, C‘66 Maxine Waters Lani Guinier 1998 Gwendolyn Brooks Alexine Clement Jackson, C‘56 William H. Cosby 1986 Jackie Joyner Kersee Faye Wattleton Louis Stokes Lena Horne Aurelia E. Brazeal, C‘65 Jacob Lawrence Johnnetta Betsch Cole 1987 Leontyne Price Dorothy Cotton Earl Graves Donald M. Stewart 1999 Selma Burke Marcelite Jordan Harris, C‘64 1988 Pearl Primus Lee Lorch Dame Ruth Nita Barrow Jewel Limar Prestage 1989 Camille Hanks Cosby Deborah Prothrow-Stith, C‘75 * Former Student As of November 2019 Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Max Cleland Herschelle Sullivan Challenor, C’61 Maxine D. -

Jenish Ysmanov Tenor

AIMARTISTS JENISH YSMANOV TENOR The tenor Jenish Ysmanov studied at the Kyrgyz National Conservatory in his home-town of Bishkek. Subsequently he participated in the Placido Domingo Academy in Valencia in Italy. He made his German debut in 2018 as Rodolfo (La bohème) at the Immling Festival, where he returned to in 2019 as Don Ottavio (Don Giovanni). In February 2020 he made his role and house debut as Rodolfo (Luisa Miller) at the Opera Ljubljana. He has already performed on international stages with the role of Rodolfo (La bohème) and has appeared at numerous opera houses in Italy as Alfredo (La traviata) and Il Duca di Mantova (Rigoletto). At the Teatro Verdi in Sassari he sang in Nino Rota's La notte di un nevrastenico and I due timidi the roles of Lui and Raimondo. He also performed as Raimondo at the Teatro Malibran in Venice. In addition to opera engagements, he participated in numerous concerts, including Gala concert in the Arena di Verona 2013, Concert in honor of Enrico Caruso in St. Petersburg 2013, Gala concert in Modena under the baton of Riccardo Muti in memory of Luciano Pavarotti's 80th birthday in 2015 and Mozart’s Requiem at the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino 2016. Jenish Ysmanov has been awarded numerous international prizes, including first prize in the Shabyt 2006 International Competition in Astana (Kazakhstan) and first prize in the 2007 Bibigul Tbelnova competition in Almaty (Kazakhstan). In 2008 he won the International Rimsky Korsakov Competition St. Petersburg, the first prize in the International Luciano Pavarotti Competition in St. -

Bellini's Norma

Bellini’s Norma - A discographical survey by Ralph Moore There are around 130 recordings of Norma in the catalogue of which only ten were made in the studio. The penultimate version of those was made as long as thirty-five years ago, then, after a long gap, Cecilia Bartoli made a new recording between 2011 and 2013 which is really hors concours for reasons which I elaborate in my review below. The comparative scarcity of studio accounts is partially explained by the difficulty of casting the eponymous role, which epitomises bel canto style yet also lends itself to verismo interpretation, requiring a vocalist of supreme ability and versatility. Its challenges have thus been essayed by the greatest sopranos in history, beginning with Giuditta Pasta, who created the role of Norma in 1831. Subsequent famous exponents include Maria Malibran, Jenny Lind and Lilli Lehmann in the nineteenth century, through to Claudia Muzio, Rosa Ponselle and Gina Cigna in the first part of the twentieth. Maria Callas, then Joan Sutherland, dominated the role post-war; both performed it frequently and each made two bench-mark studio recordings. Callas in particular is to this day identified with Norma alongside Tosca; she performed it on stage over eighty times and her interpretation casts a long shadow over. Artists since, such as Gencer, Caballé, Scotto, Sills, and, more recently, Sondra Radvanovsky have had success with it, but none has really challenged the supremacy of Callas and Sutherland. Now that the age of expensive studio opera recordings is largely over in favour of recording live or concert performances, and given that there seemed to be little commercial or artistic rationale for producing another recording to challenge those already in the catalogue, the appearance of the new Bartoli recording was a surprise, but it sought to justify its existence via the claim that it authentically reinstates the integrity of Bellini’s original concept in matters such as voice categories, ornamentation and instrumentation. -

Verdi's Rigoletto

Verdi’s Rigoletto - A discographical conspectus by Ralph Moore It is hard if not impossible, to make a representative survey of recordings of Rigoletto, given that there are 200 in the catalogue; I can only compromise by compiling a somewhat arbitrary list comprising of a selection of the best-known and those which appeal to me. For a start, there are thirty or so studio recordings in Italian; I begin with one made in 1927 and 1930, as those made earlier than that are really only for the specialist. I then consider eighteen of the studio versions made since that one. I have not reviewed minor recordings or those which in my estimation do not reach the requisite standard; I freely admit that I cannot countenance those by Sinopoli in 1984, Chailly in 1988, Rahbari in 1991 or Rizzi in 1993 for a combination of reasons, including an aversion to certain singers – for example Gruberova’s shrill squeak of a soprano and what I hear as the bleat in Bruson’s baritone and the forced wobble in Nucci’s – and the existence of a better, earlier version by the same artists (as with the Rudel recording with Milnes, Kraus and Sills caught too late) or lacklustre singing in general from artists of insufficient calibre (Rahbari and Rizzi). Nor can I endorse Dmitri Hvorostovsky’s final recording; whether it was as a result of his sad, terminal illness or the vocal decline which had already set in I cannot say, but it does the memory of him in his prime no favours and he is in any case indifferently partnered. -

She Graduates in Singing at the Conservatory of Her City

Nana Miriani Born in Tbilisi (Georgia), she graduates in singing at the Conservatory of her city. In Italy she attended the Chigiana Academy and the Course of Training and Improvement of the Academy of Singing "Arturo Toscanini" in Parma, under the guidance of Maestro Tenor Carlo Bergonzi, obtaining certificates of merit and scholarships. In 2000-2001 she attended the Specialization Course of Vocal Interpretation "Verdi Opera Studio", "Foundation Verdi Festival" at the Theatre Regio in Parma, under the guidance of Soprano Renata Scotto. She made her debut in 1998 inBusseto, playing the role of Abigaille in Nabucco by G. Verdi, conducted by Maestro Romano Gandolfi, with the Symphony Orchestra of Emilia Romagna "Arturo Toscanini" and Chorus of the Theatre Regio of Parma, in the presence of the President of the French Republic. In 2001, she sang in the Festival "Radio France", for the Opera Berlioz in Montpellier, in Cavalleria Rusticana by D. Monleone and in Resurrezione by F. Alfano, conducted by Maestro Friedemann Layer, with CD recording. During her career she played the roles of: Tosca in Tosca by G. Puccini, engaged at the Teatro alla Scala in Milan, conducted by Maestro Lorin Maazel and directed by Luca Ronconi (2006), and at the National Theatre in Bratislava (2002, 2003, 2004) Abigaille in Nabucco by G. Verdi, at the Teatro Lirico in Cagliari, conducted by Maestro Antonello Allemandi and directed by Daniele Abbado, at Theatre Bielefeld, Germany (2006), at the Wielki Theatre in Poznan, Poland (2006), at the State Opera Z. Paliashvili of Tbilisi, alongside bass Paata Burchuladze and baritone Lado Ataneli (2009), at the Festival Steinbruch Rohrdorf of Munich, Germany (2009), at the National State Opera A. -

Rigoletto Teatro A.Bonci in Cesena,Italy and This Will Be Repeated at the Ravenna Festival in April 2013

companies: Teatro alla Scala, Scarlatti Orchestra in Naples, the Swiss Italian Radio Orchestra, Teatro Regio di Parma, Claudio Monteverdi Orchestra, Haydn Orchestra in Bolzano, Orchestra Sinfonica Nazionale della RAI, Rome Symphony Orchestra. NOVEMBER 09 DECEMBER 09 Cristina Alunno mezzo-soprano after graduation she continued studying with Gabriella Morigi and she has taken master classes with Renata Scotto at the Accademia Santa Cecilia in Rome .She recently sang the title role of Dido in "Dido and Aeneas" by H.Purcell under the direction of Maestro Luca Giardini at the Rigoletto Teatro A.Bonci in Cesena,Italy and this will be repeated at the Ravenna Festival in April 2013. She performed in Madama Butterfly by G.Puccini under the direction of Maestro Paolo Olmi in Cesena. She di G.Verdi has also performed in Der Abschied by G. Mahler, at the Palazzo Albrizzi in Venice. Cristina was Lola in the Cavalleria Rusticana by P.Mascagni, in Bologna , she has performed in La Finta Giardiniera by WA Mozart in Perugia ,Italy and has performed in concerts at the Palazzo Farnese in Rome, at the Auditorium in Forma di Concerto Parco della Musica in Rome, at the Festival "Il Serchio delle Muse" in Lucca ,Italy, at the Teatro Chico Santa Cruz de la Palma, Canary Islands, and at the Ordem dos Medicos Concert Hall in Porto, Portugal. performed by Marco Simonelli graduated in singing at the Conservatory G B Martini in Bologna and continued his Giuseppe Deligia (Baritone) studies with Gabriella Morigi and with M° Luigi Roni.He has taken master classes with Renata Scotto at Monica De Rosa McKay ( Soprano) the Accademia Santa Cecilia in Rome. -

11-03-2018 Carmen Eve.Indd

GEORGES BIZET carmen conductor Opera in four acts Omer Meir Wellber Libretto by Henri Meilhac and production Sir Richard Eyre Ludovic Halévy, based on the novella by Prosper Mérimée set and costume designer Rob Howell Saturday, November 3, 2018 lighting designer 1:00–4:25 PM Peter Mumford choreographer Christopher Wheeldon revival stage director Paula Williams The production of Carmen was made possible by a generous gift from Mrs. Paul Desmarais Sr. general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2018–19 SEASON The 1,012th Metropolitan Opera performance of GEORGES BIZET’S carmen conductor Omer Meir Wellber in order of vocal appearance mor alès le dancaïre Adrian Timpau** Javier Arrey micaël a le remendado Guanqun Yu Scott Scully don josé Yonghoon Lee solo dancers Maria Kowroski zuniga Martin Harvey Richard Bernstein carmen Clémentine Margaine fr asquita Sydney Mancasola mercédès Sarah Mesko escamillo Kyle Ketelsen Saturday, November 3, 2018, 1:00–4:25PM MARTY SOHL / MET OPERA Clémentine Margaine Chorus Master Donald Palumbo in the title role of Musical Preparation Derrick Inouye, Liora Maurer, and Bizet’s Carmen Bénédicte Jourdois* Fight Director J. Allen Suddeth Assistant Stage Directors Sara Erde and Jonathon Loy Stage Band Conductor Jeffrey Goldberg Met Titles Sonya Friedman Children’s Chorus Director Anthony Piccolo Movement Coach Sara Erde Associate Costume Designer Irene Bohan Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted by Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Art for Art Theater Service GmbH, Vienna; Justo Algaba S.L., Madrid; Carelli Costumes, New York, and Metropolitan Opera Costume Department Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department This production uses gunshot effects. -

Michael Schade at a Special Release of His New Hyperion Recording “Of Ladies and Love...”

th La Scena Musicale cene English Canada Special Edition September - October 2002 Issue 01 Classical Music & Jazz Season Previews & Calendar Southern Ontario & Western Canada MichaelPerpetual Schade Motion Canada Post Publications Mail Sales Agreement n˚. 40025257 FREE TMS 1-01/colorpages 9/3/02 4:16 PM Page 2 Meet Michael Schade At a Special Release of his new Hyperion recording “Of ladies and love...” Thursday Sept.26 At L’Atelier Grigorian Toronto 70 Yorkville Ave. 5:30 - 7:30 pm Saturday Sept. 28 At L’Atelier Grigorian Oakville 210 Lakeshore Rd.E. 1:00 - 3:00 pm The World’s Finest Classical & Jazz Music Emporium L’Atelier Grigorian g Yorkville Avenue, U of T Bookstore, & Oakville GLENN GOULD A State of Wonder- The Complete Goldberg Variations (S3K 87703) The Goldberg Variations are Glenn Gould’s signature work. He recorded two versions of Bach’s great composition—once in 1955 and again in 1981. It is a testament to Gould’s genius that he could record the same piece of music twice—so differently, yet each version brilliant in its own way. Glenn Gould— A State Of Wonder brings together both of Gould’s legendary performances of The Goldberg Variations for the first time in a deluxe, digitally remastered, 3-CD set. Sony Classical celebrates the 70th anniversary of Glenn Gould's birth with a collection of limited edition CDs. This beautifully packaged collection contains the cornerstones of Gould’s career that marked him as a genius of our time. A supreme intrepreter of Bach, these recordings are an essential addition to every music collection.