Warren Jones Oral History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARSC Journal

A Discography of the Choral Symphony by J. F. Weber In previous issues of this Journal (XV:2-3; XVI:l-2), an effort was made to compile parts of a composer discography in depth rather than breadth. This one started in a similar vein with the realization that SO CDs of the Beethoven Ninth Symphony had been released (the total is now over 701). This should have been no surprise, for writers have stated that the playing time of the CD was designed to accommodate this work. After eighteen months' effort, a reasonably complete discography of the work has emerged. The wonder is that it took so long to collect a body of information (especially the full names of the vocalists) that had already been published in various places at various times. The Japanese discographers had made a good start, and some of their data would have been difficult to find otherwise, but quite a few corrections and additions have been made and some recording dates have been obtained that seem to have remained 1.Dlpublished so far. The first point to notice is that six versions of the Ninth didn't appear on the expected single CD. Bl:lhm (118) and Solti (96) exceeded the 75 minutes generally assumed (until recently) to be the maximum CD playing time, but Walter (37), Kegel (126), Mehta (127), and Thomas (130) were not so burdened and have been reissued on single CDs since the first CD release. On the other hand, the rather short Leibowitz (76), Toscanini (11), and Busch (25) versions have recently been issued with fillers. -

Eastman School of Music, Thrill Every Time I Enter Lowry Hall (For- Enterprise of Studying, Creating, and Loving 26 Gibbs Street, Merly the Main Hall)

EASTMAN NOTESFALL 2015 @ EASTMAN Eastman Weekend is now a part of the University of Rochester’s annual, campus-wide Meliora Weekend celebration! Many of the signature Eastman Weekend programs will continue to be a part of this new tradition, including a Friday evening headlining performance in Kodak Hall and our gala dinner preceding the Philharmonia performance on Saturday night. Be sure to join us on Gibbs Street for concerts and lectures, as well as tours of new performance venues, the Sibley Music Library and the impressive Craighead-Saunders organ. We hope you will take advantage of the rest of the extensive Meliora Weekend programming too. This year’s Meliora Weekend @ Eastman festivities will include: BRASS CAVALCADE Eastman’s brass ensembles honor composer Eric Ewazen (BM ’76) PRESIDENTIAL SYMPOSIUM: THE CRISIS IN K-12 EDUCATION Discussion with President Joel Seligman and a panel of educational experts AN EVENING WITH KEYNOTE ADDRESS EASTMAN PHILHARMONIA KRISTIN CHENOWETH BY WALTER ISAACSON AND EASTMAN SCHOOL The Emmy and Tony President and CEO of SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Award-winning singer the Aspen Institute and Music of Smetana, Nicolas Bacri, and actress in concert author of Steve Jobs and Brahms The Class of 1965 celebrates its 50th Reunion. A highlight will be the opening celebration on Friday, featuring a showcase of student performances in Lowry Hall modeled after Eastman’s longstanding tradition of the annual Holiday Sing. A special medallion ceremony will honor the 50th class to commemorate this milestone. The sisters of Sigma Alpha Iota celebrate 90 years at Eastman with a song and ritual get-together, musicale and special recognition at the Gala Dinner. -

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers NMAH.AC.0584 Reuben Jackson and Wendy Shay 2015 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Music Manuscripts and Sheet Music, 1919 - 1973................................... 5 Series 2: Photographs, 1939-1990........................................................................ 21 Series 3: Scripts, 1957-1981.................................................................................. 64 Series 4: Correspondence, 1960-1996................................................................. -

Network Notebook

Network Notebook Fall Quarter 2018 (October - December) 1 A World of Services for Our Affiliates We make great radio as affordable as possible: • Our production costs are primarily covered by our arts partners and outside funding, not from our affiliates, marketing or sales. • Affiliation fees only apply when a station takes three or more programs. The actual affiliation fee is based on a station’s market share. Affiliates are not charged fees for the selection of WFMT Radio Network programs on the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). • The cost of our Beethoven and Jazz Network overnight services is based on a sliding scale, depending on the number of hours you use (the more hours you use, the lower the hourly rate). We also offer reduced Beethoven and Jazz Network rates for HD broadcast. Through PRX, you can schedule any hour of the Beethoven or Jazz Network throughout the day and the files are delivered a week in advance for maximum flexibility. We provide highly skilled technical support: • Programs are available through the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). PRX delivers files to you days in advance so you can schedule them for broadcast at your convenience. We provide technical support in conjunction with PRX to answer all your distribution questions. In cases of emergency or for use as an alternate distribution platform, we also offer an FTP (File Transfer Protocol), which is kept up to date with all of our series and specials. We keep you informed about our shows and help you promote them to your listeners: • Affiliates receive our quarterly Network Notebook with all our program offerings, and our regular online WFMT Radio Network Newsletter, with news updates, previews of upcoming shows and more. -

8.112023-24 Bk Menotti Amelia EU 26-03-2010 9:41 Pagina 16

8.112023-24 bk Menotti Amelia_EU 26-03-2010 9:41 Pagina 16 Gian Carlo MENOTTI Also available The Consul • Amelia al ballo LO M CAR EN N OT IA T G I 8.669019 19 gs 50 din - 1954 Recor Patricia Neway • Marie Powers • Cornell MacNeil 8.669140-41 Orchestra • Lehman Engel Margherita Carosio • Rolando Panerai • Giacinto Prandelli Chorus and Orchestra of La Scala, Milan • Nino Sanzogno 8.112023-24 16 8.112023-24 bk Menotti Amelia_EU 26-03-2010 9:41 Pagina 2 MENOTTI CENTENARY EDITION Producer’s Note This CD set is the first in a series devoted to the compositions, operatic and otherwise, of Gian Carlo Menotti on Gian Carlo the occasion of his centenary in 2011. The recordings in this series date from the mid-1940s through the late 1950s, and will feature several which have never before appeared on CD, as well as some that have not been available in MENOTTI any form in nearly half a century. The present recording of The Consul, which makes its CD début here, was made a month after the work’s (1911– 2007) Philadelphia première. American Decca was at the time primarily a “pop” label, the home of Bing Crosby and Judy Garland, and did not yet have much experience in the area of Classical music. Indeed, this recording seems to have been done more because of the work’s critical acclaim on the Broadway stage than as an opera, since Decca had The Consul also recorded Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman with members of the original cast around the same time. -

Greenup County, You Have a of June in Pike County

J.D. Crowe Table of Contents US23CountryMusicHighway......................4 The Future Stars of Country Music.................5 “More Than Music” US 23 Driving Tour.............8 Billy Ray Cyrus........................................9 Greenbo Lake State Resort Park...................10 Jesse Stuart..........................................11 The Judds.............................................12 Boyd County Tourism.................................13 Ricky Skaggs.........................................15 Lawrence County Tourism............................16 Larry Cordle..........................................18 Loretta Lynn & Crystal Gayle.......................19 US 23: John Boy’s Country .....................20 Hylo Brown...........................................21 Johnson County Tourism..............................22 Dwight Yoakam.......................................23 Map....................................................24 The Jenny Wiley Story.............................27 Presonsburg Tourism..................................28 Elk in Eastern Kentucky..............................30 Patty Loveless.......................................33 Pikeville/Pike County Tourism........................37 The banjo on the cover of this year’s magazine is a Hatfields and McCoys...............................38 Gibson owned by JD Crowe.JDwasbornandraisedin Gary Stewart........................................39 Lexington, Kentucky, and was one of the most influential Marion Sumner.......................................39 bluegrass musicians. -

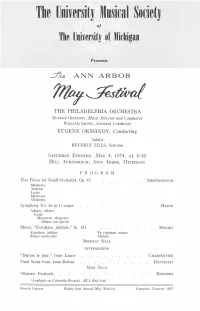

The Uuiversitj Musical Souietj of the University of Michigan

The UuiversitJ Musical SouietJ of The University of Michigan Presents ANN ARBOR THE PHILADELPHIA ORCHESTRA E UGENE ORMANDY , Music Director and Conduct01' WILLIAM SMITH, Assistant Conductor EUGENE ORMANDY, Conducting Soloist BEVERLY SILLS, Soprano SATURDAY EVENING , MAY 4, 1974, AT 8 :30 HILL AUDITORIUM , ANN ARBOR , MICHIGAN PROGRAM Five Pieces for Small Orchestra, Op. 42 SHOSTAKOVI CH Moderato Andante Largo Moderato Allegretto Symphony No. 88 in G major HAYDN Adagio; allegro La rgo Menuetto : a llegretto Allegro con spirito Motet, "Exsultate, jubilate," K. 165 MOZART Exsul tate, jubilate Tu virginum corona Fulge t arnica di es .-\lIelu ja BEVERL Y S ILLS IN TERiVIISSION " Depuis Ie jour," fr om Louise CHARPENTIER Fin al Scene from Anna Bolena DON IZETTl MISS SILLS ';'Roman Festivals R ESPIGHI *A vailable on Columbia R ecords RCA R ed Seal F ourth Concert Eighty-first Annua l May Festi n ll Complete Conce rts 3885 PROGRAM NOTES by G LENN D. MCGEOCH Five Pieces for Small Orchestra, Op. 42 DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906- ) The Fi ve Pieces, written by Shostakovich at the age of twenty-nine, were never mentioned or listed among his major works, until Ivan M artynov, in a monograph ( 1947) referred to them as "Five Fragments for Orchestra, 193 5 manuscript, op. 42." A conflict, which had begun to appear between the compose r's natura l, but advanced expression, and the Soviet official sanction came to a climax in 1934 wh en he produced his "avant guarde" opera Lady Ma cbeth of Mzensk. He was accuse d of "deliberate musical affectation " and of writing "un Soviet, eccent ric music, founded upon formalistic ideas of bourge ois musical conce ptions." Responding to this official castigation, he wrote a se ries of short, neoclassic, understated works, typical of the Fi ve Pieces on tonight's program. -

Recordings of Mahler Symphony No. 4

Recordings of Mahler Symphony No. 4 by Stan Ruttenberg, President, Colorado MahlerFest SUMMARY After listening to each recording once or twice to get the general feel, on bike rides, car trips, while on the Internet etc, I then listened more carefully, with good headphones, following the score. They are listed in the survey in about the order in which I listened, and found to my delight, and disgust, that as I went on I noticed more and more details to which attention should be paid. Lack of time and adequate gray matter prevented me from going back and re-listening all over again, except for the Mengelberg and Horenstein recordings, and I did find a few points to change or add. I found that JH is the ONLY conductor to have the piccolos play out adequately in the second movement, and Claudio Abbado with the Vienna PO is the only conductor who insisted on the two horn portamenti in the third movement.. Stan's prime picks: Horenstein, Levine, Reiner, Szell, Skrowaczewski, von Karajan, Abravanel, in that order, but the rankings are very close. Also very good are Welser- Most, and Klemperer with Radio Orchestra Berlin, and Berttini at Cologne. Not one conductor met all my tests of faithfulness to the score in all the too many felicities therein, but these did the best and at the same time produced a fine overall performance. Mengelberg, in a class by himself, should be heard for reference. Stan's soloist picks: Max Cencic (boy soprano with Nanut), in a class by himself. Then come, not in order, Davrath (Abravanel), Mathes (von Karajan), Trötschel (Klemperer BRSO), Raskin (Szell), Blegen (Levine), Della Casa (Reiner), Irmgard Seefried (Walter), Jo Vincent (Mengelberg), Ameling (Haitink RCOA), Ruth Zeisek (Gatti), Margaret Price with Horenstein, and Kiri Te Kanawa (Solti), Szell (Rattle broadcast), and Battle (Maazel). -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

Prefaces to Scalia/Ginsburg: a (Gentle) Parody of Operatic Proportions

WANG, SCALIA/GINSBURG: A (GENTLE) PARODY OF OPERATIC PROPORTIONS, 38 COLUM. J.L. & ARTS 237 (2015) Prefaces to Scalia/Ginsburg: A (Gentle) Parody of Operatic Proportions Preface by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg: Scalia/Ginsburg is for me a dream come true. If I could choose the talent I would most like to have, it would be a glorious voice. I would be a great diva, perhaps Renata Tebaldi or Beverly Sills or, in the mezzo range, Marilyn Horne. But my grade school music teacher, with brutal honesty, rated me a sparrow, not a robin. I was told to mouth the words, never to sing them. Even so, I grew up with a passion for opera, though I sing only in the shower, and in my dreams. One fine day, a young composer, librettist and pianist named Derrick Wang approached Justice Scalia and me with a request. While studying Constitutional Law at the University of Maryland Law School, Wang had an operatic idea. The different perspectives of Justices Scalia and Ginsburg on constitutional interpretation, he thought, could be portrayed in song. Wang put his idea to the “will it write” test. He composed a comic opera with an important message brought out in the final duet, “We are different, we are one”—one in our reverence for the Constitution, the U.S. judiciary and the Court on which we serve. Would we listen to some excerpts from the opera, Wang asked, and then tell him whether we thought his work worthy of pursuit and performance? Good readers, as you leaf through the libretto, check some of the many footnotes disclosing Wang’s sources, and imagine me a dazzling diva, I think you will understand why, in answer to Wang’s question, I just said “Yes.” Preface by Justice Antonin Scalia: While Justice Ginsburg is confident that she has achieved her highest and best use as a Supreme Justice, I, alas, have the nagging doubt that I could have been a contendah—for a divus, or whatever a male diva is called. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

RSTD OPERN Ma Rz April Ok 212X433

RSTD OPERN_März April_ok_212x433 12.02.13 09:40 Seite 1 Opernprogramm März 2013 März Gaetano Donizetti Anna Bolena 20.00 - 22.55 Anna Bolena: Edita Gruberova, Giovanna Seymour: Delores Ziegler, Enrico VIII.: Stefano Palatchi, Lord Rochefort: Igor Morosow, 2 Lord Riccardo Percy: José Bros, Smeton: Helene Schneiderman, Sir Hervey: José Guadalupe Reyes. Samstag Chor und Orchester des Ungarischen Rundfunks und Fernsehens, Leitung: Elio Boncompagni, 1994. März Richard Wagner Das Liebesverbot 20.00 - 22.40 Friedrich: Hermann Prey, Luzio: Wolfgang Fassler, Claudio: Robert Schunk, Antonio: Friedrich Lenz, Angelo: Kieth Engen, 5 Isabella: Sabine Hass, Mariana: Pamela Coburn, Brighella: Alfred Kuhn. Dienstag Chor der Bayerischen Staatsoper, Bayerisches Staatsorchester, Leitung: Wolfgang Sawallisch, 1983. März Georg Friedrich Händel Alessandro 20.00 - 23.20 Alessandro Magno: Max Emanuel Cencic, Rossane: Julia Lezhneva, Lisaura: Karina Gauvin, Tassile: Xavier Sabata, 7 Leonato: Juan Sancho, Clito: In-Sung Sim, Cleone: Vasily Khoroshev. Donnerstag The City of Athens Choir, Armonia Atenea, Leitung: George Petrou, 2011. März Giuseppe Verdi Aroldo 20.00 - 22.15 Aroldo: Neil Shicoff, Mina: Carol Vaness, Egberto: Anthony Michaels-Moore, Briano: Roberto Scandiuzzi, 9 Godvino: Julian Gavin, Enrico: Sergio Spina, Elena: Marina Comparato. Samstag Coro del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, Orchestra del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, Leitung: Zubin Mehta, 2001. März Wolfgang Amadé Mozart La finta giardiniera 20.00 - 23.10 Sandrina: Sophie Karthäuser, Contino Belfiore: Jeremy Ovenden, Arminda: Alex Penda, 12 Cavaliere Ramiro: Marie-Claude Chappuis, Podestà: Nicolas Rivenq, Serpetta: Sunhae Im, Roberto: Michael Nagy. Dienstag Freiburger Barockorchester, Leitung: René Jacobs, 2011. Der neue Konzertzyklus im Mozarthaus Vienna: mozartakademie 2013 „Magic Moments – Magische Momente in den Werken großer Meister“ 20.03.