Reviewseviews 85

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New International Manual of Braille Music Notation by the Braille Music Subcommittee World Blind Union

1 New International Manual Of Braille Music Notation by The Braille Music Subcommittee World Blind Union Compiled by Bettye Krolick ISBN 90 9009269 2 1996 2 Contents Preface................................................................................ 6 Official Delegates to the Saanen Conference: February 23-29, 1992 .................................................... 8 Compiler’s Notes ............................................................... 9 Part One: General Signs .......................................... 11 Purpose and General Principles ..................................... 11 I. Basic Signs ................................................................... 13 A. Notes and Rests ........................................................ 13 B. Octave Marks ............................................................. 16 II. Clefs .............................................................................. 19 III. Accidentals, Key & Time Signatures ......................... 22 A. Accidentals ................................................................ 22 B. Key & Time Signatures .............................................. 22 IV. Rhythmic Groups ....................................................... 25 V. Chords .......................................................................... 30 A. Intervals ..................................................................... 30 B. In-accords .................................................................. 34 C. Moving-notes ............................................................ -

Dictionary of Braille Music Signs by Bettye Krolick

JBN 0-8444-0 9 C D E F G Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Federation of the Blind (NFB) http://archive.org/details/dictionaryofbraiOObett LIBRARY IOWA DEPARTMENT FOR THE BLIND 524 Fourth Street Des Moines, Iowa 50309-2364 Dictionary of Braille Music Signs by Bettye Krolick National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 20542 1979 MT. PLEASANT HIGH SCHOOL LIBRARY Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Krolick, Bettye. Dictionary of braille music signs. At head of title: National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, Library of Congress. Bibliography: p. 182-188 Includes index. 1. Braille music-notation. I. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. II. Title. MT38.K76 78L.24 78-21301 ISBN 0-8444-0277-X . TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD vii PREFACE ix HISTORY OF THE BRAILLE MUSIC CODE ... xi HOW TO LOCATE A DEFINITION xviii DICTIONARY OF SIGNS (A sign that contains two or more cells is listed under its first character.) . 1 •* 1 •• 16 • • •• 3 •• 17 •> 6 •• 17 •• •• 7 •• 17 •• 7 •• 17 •• •• 7 •• 17 •• •• 8 •• 18 •• •• 8 •• 18 •• •• 9 •• 19 •• •• 9 •• 19 • • •• 10 •• 20 • • •• 12 •• 20 •• 14 •• 20 •• •• 14 •• 22 • • •• •• 15 • • 27 •• •• •« •• 15 • • 29 •• • • •« 16 30 •• •• 16 • • 30 30 i: 46 ?: 31 11 47 r. 31 ;: 48 •: 31 i? 58 ?: 31 i; 78 ::' 34 :: 79 a 34 ;: si 35 ;? 86 37 ;: 90 39 ':• 96 40 ;: 102 43 i: 105 45 ;: 113 46 FORMATS FOR BRAILLE MUSIC 122 Format Identification Chart 125 Music in Parallels -

Music Braille Code, 2015

MUSIC BRAILLE CODE, 2015 Developed Under the Sponsorship of the BRAILLE AUTHORITY OF NORTH AMERICA Published by The Braille Authority of North America ©2016 by the Braille Authority of North America All rights reserved. This material may be duplicated but not altered or sold. ISBN: 978-0-9859473-6-1 (Print) ISBN: 978-0-9859473-7-8 (Braille) Printed by the American Printing House for the Blind. Copies may be purchased from: American Printing House for the Blind 1839 Frankfort Avenue Louisville, Kentucky 40206-3148 502-895-2405 • 800-223-1839 www.aph.org [email protected] Catalog Number: 7-09651-01 The mission and purpose of The Braille Authority of North America are to assure literacy for tactile readers through the standardization of braille and/or tactile graphics. BANA promotes and facilitates the use, teaching, and production of braille. It publishes rules, interprets, and renders opinions pertaining to braille in all existing codes. It deals with codes now in existence or to be developed in the future, in collaboration with other countries using English braille. In exercising its function and authority, BANA considers the effects of its decisions on other existing braille codes and formats, the ease of production by various methods, and acceptability to readers. For more information and resources, visit www.brailleauthority.org. ii BANA Music Technical Committee, 2015 Lawrence R. Smith, Chairman Karin Auckenthaler Gilbert Busch Karen Gearreald Dan Geminder Beverly McKenney Harvey Miller Tom Ridgeway Other Contributors Christina Davidson, BANA Music Technical Committee Consultant Richard Taesch, BANA Music Technical Committee Consultant Roger Firman, International Consultant Ruth Rozen, BANA Board Liaison iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................................................. -

November 2.0 EN.Pages

Over 1000 Symbols More Beautiful than Ever SMuFL Compliant Advanced Support in Finale, Sibelius & LilyPond DocumentationAn Introduction © Robert Piéchaud 2015 v. 2.0.1 published by www.klemm-music.de — November 2.0 Documentation — Summary Foreword .........................................................................................................................3 November 2.0 Character Map .........................................................................................4 Clefs ............................................................................................................................5 Noteheads & Individual Notes ...................................................................................13 Noteflags ...................................................................................................................42 Rests ..........................................................................................................................47 Accidentals (Standard) ...............................................................................................51 Microtonal & Non-Standard Accidentals ....................................................................56 Articulations ..............................................................................................................72 Instrument Techniques ...............................................................................................83 Fermatas & Breath Marks .........................................................................................121 -

Higher Home Learning Tasks

„Higher‟ Homework Workbook “Understanding Music” Listening & Literacy Replacement Copy Cost: 50p 1 “H” Homework Workbook 2016 1 HOMEWORK DUE DATES Title Date due Assignment 121 WRITING MUSIC I Assignment 122 WHAT‟S THE GENRE? I Assignment 123 TIME SIGNATURES I Assignment 124 NAME THAT STYLE I Assignment 125 LITERACY QUIZ I Assignment 126 CONCEPT MATCHING I Assignment 127 NOTE NAMING I Assignment 128 STRUCTURES & FORMS I Assignment 129 WRITING MUSIC II Assignment 130 DYNAMICS I Assignment 131 INTERVALS I Assignment 132 CONCEPT DETECTIVE WORK I Assignment 133 KEY SIGNATURES, SCALES & CHORDS I Assignment 134 WHATS THE GENRE? II Assignment 135 LITERACY QUIZ II Assignment 136 NAME THAT STYLE II Assignment 137 NOTE NAMING II Assignment 138 DEFINE THAT CONCEPT I Assignment 139 WRITING MUSIC III Assignment 140 INTERVALS II Assignment 141 KEY SIGNATURES, SCALES & CHORDS II Assignment 142 WHAT IS MINIMALISM? Assignment 143 REPETITION & SEQUENCE I 2 “H” Homework Workbook 2016 2 Title Date due Assignment 144 WHATS THE GENRE? III Assignment 145 LITERACY QUIZ III Assignment 146 CONCEPT MATCHING II Assignment 147 NOTE NAMING III Assignment 148 INSTRUMENTS OF THE ORCHESTRA I Assignment 149 WRITING MUSIC IV Assignment 150 KEY SIGNATURES, SCALES & CHORDS III Assignment 151 INTERVALS III Assignment 152 CONCEPT DETECTIVE WORK II Assignment 153 TIME SIGNATURES II Assignment 154 STRUCTURES & FORMS II Assignment 155 LITERACY QUIZ IV Assignment 156 WHATS THE GENRE? IV Assignment 157 NOTE NAMING IV Assignment 158 DEFINE THAT CONCEPT II Assignment 159 WRITING MUSIC V Assignment 160 LITERACY QUIZ V 3 “H” Homework Workbook 2016 3 ASSIGNMENT #121 Writing Music I When writing music it needs to be done as neatly as possible; the information in a piece of music is read, and has to be understood at very high speeds so neatness is VERY important. -

Repeated Musical Patterns

SECONDARY/KEY STAGE 3 MUSIC – HOOKS AND RIFFS 5 M I N UTES READING Repeated Musical Patterns 5 MINUTES READING #1 Repetition is important in music where sounds or sequences are often “Essentially my repeated. While repetition plays a role in all music, it is especially prominent contribution was to in specific styles. introduce repetition into Western music “Repetition is part and parcel of symmetry. You may find a short melody or a as the main short rhythm that you like and you repeat it through the course of a melody or ingredient without song. This sort of repetition helps to unify your melody and serves as an any melody over it, identifying factor for listeners. However, too much of a good thing can get without anything just patterns, annoying. If you repeat a melody or rhythm too often, it will start to bore the musical patterns.” listener”. (Miller, 2005) - Terry Riley “Music is based on repetition...Music works because we remember the sounds we have just heard and relate them to ones that are just now being played. Repetition, when done skillfully by a master composer, is emotionally satisfying to our brains, and makes the listening experience as pleasurable as it is”. (Levitin, 2007) During the Eighteenth Century, musical concerts were high-profile events and because someone who liked a piece of music could not listen to it again, musicians and composers had to think of a way to make the music ‘sink in’. Therefore, they would repeat parts of their songs or music at times, making Questions to think about: their music repetitive, without becoming dull. -

Musical Symbols Range: 1D100–1D1FF

Musical Symbols Range: 1D100–1D1FF This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 This file may be changed at any time without notice to reflect errata or other updates to the Unicode Standard. See https://www.unicode.org/errata/ for an up-to-date list of errata. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/ for access to a complete list of the latest character code charts. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/Unicode-14.0/ for charts showing only the characters added in Unicode 14.0. See https://www.unicode.org/Public/14.0.0/charts/ for a complete archived file of character code charts for Unicode 14.0. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the online reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0, online at https://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode14.0.0/, as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24, #29, #31, #34, #38, #41, #42, #44, #45, and #50, the other Unicode Technical Reports and Standards, and the Unicode Character Database, which are available online. See https://www.unicode.org/ucd/ and https://www.unicode.org/reports/ A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation. -

Presentation

Over 1200 Symbols More Beautiful than Ever SMuFL Compliant Advanced Support in Finale, Dorico, Sibelius & LilyPond Presentation © Robert Piéchaud 2016 v. 2.1.0 published by www.klemm-music.de — November 2 Presentation — Summary Foreword 3 November 2.1 Character Map 4 Clefs 5 Noteheads & Individual Notes 12 Noteflags 38 Rests 42 Accidentals (standard) 46 Microtonal & Non-Standard Accidentals 50 Articulations 63 Instrument Techniques 72 Fermatas & Breath Marks 105 Dynamics 110 Ornaments & Arpeggios 115 Repeated Lines & Other “Wiggles” 126 Octaves 132 Time Signatures & Other Numbers 134 Tempo Marking Items 141 Medieval Notation 145 Miscellaneous Symbols 150 Score Examples 163 Renaissance 163 Baroque 164 Bach 165 Early XXth Century 166 Ravel 167 XXIst Century 168 Requirements & Installation 169 Finale 169 Dorico 169 Sibelius 169 LilyPond 170 Free Technical Assistance 171 About the Designer 172 Credits 172 2 — November 2 Presentation — Foreword Welcome to November 2! November has been praised for years by musicians, publishers and engravers as one of the finest and most vivid fonts ever designed for music notation programs. For use in programs such as Finale, Dorico, Sibelius or LilyPond, November 2 now includes a astonishing variety of symbols, from usual shapes such as noteheads, clefs and rests to rarer characters like microtonal accidentals, special instrument techniques, early clefs or orna- ments, ranging from the Renaissance1 to today’s avant-garde music. Based on the principle that each detail means as much as the whole, crafted with ultimate care, November 2 is a font of unequalled coherence. While in tune with the most recent technologies, its inspiration comes from the art of tradi- tional music engraving. -

Proposal for Encoding Western Music Symbols in ISO/IEC 10646 Andrew Hodgson

Comments on the Proposal for Encoding Western Music Symbols in ISO/IEC 10646 Andrew Hodgson I have looked over the proposal in detail with regard to its completeness and usefulness for the purpose of supporting plain text which talks about music. My comments are all in Arial font and thus should stand out from the original clearly. In many cases I am simply providing commentary without actually suggesting changes. Any paragraph which actually suggests a change has been highlighted, by starting it with "***", so you can easily skip straight to these. A set of symbols for music has (at least) the following potential uses: 1. To provide those symbols needed for the description of music in plain text. 1. To provide a set of symbols which can be used with higher level protocols, to create a graphic rendition of music. 1. To provide a set of code values which can encode the semantics of music. I believe this proposal, as part of the Unicode standard, must be useful for #1, and I have a few suggested extensions to support this. This proposal is also useful for #2. It is not at all suitable for #3. The text should emphasis the true value of the coded set and not attempt to boost the apparent value with claims which cannot be supported. I have relatively minor comments on the proposed set of symbols. My comments on the surrounding text are more significant. These fall into two categories. 1. Objections to suggestions that this set of symbols could be used for the third purpose noted above. -

Tutorial & Reference Manual

TUTORIAL & REFERENCE MANUAL Compiled by Luis E. Juan, 2002 r. 05 2 INDEX TUTORIAL .................................................................................................................................................... 9 RUNNING ENCORE ................................................................................................................................. 9 OPENING A FILE..................................................................................................................................... 9 SPLITTING THE STAFF .......................................................................................................................... 10 SETTING THE KEY SIGNATURE.............................................................................................................. 11 ADDING A PICKUP BAR......................................................................................................................... 12 ENTERING A NOTE ............................................................................................................................... 13 MIDI PLAYBACK .................................................................................................................................. 14 ADDING MEASURE NUMBERS ............................................................................................................... 17 DRAGGING TO A NEW PITCH................................................................................................................. 17 ENTERING AN ACCIDENTAL.................................................................................................................. -

FORMAL SEMANTICS for MUSIC NOTATION CONTROL FLOW As an Example, Particle Behaviours Might Include: Distributed Behavioral Model,” in ACM 1

order, to affect the trajectories of the emitted particles. [8] C. W. Reynolds, “Flocks, herds and schools: A FORMAL SEMANTICS FOR MUSIC NOTATION CONTROL FLOW As an example, particle behaviours might include: distributed behavioral model,” in ACM 1. Bounded spaces and edge effects (e.g. SIGGRAPH Computer Graphics, 1987, vol. 21, ‘bouncing’ trajectories) pp. 25–34. Zeyu Jin Roger Dannenberg 2. Interparticle attraction or repulsion [9] T. Blackwell and M. Young, “Self-organised Carnegie Mellon University Carnegie Mellon University 3. Randomized motion (e.g. drunken walks) music,” Organised Sound, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 123– 4. Dynamical non-linear systems (e.g. Lorenz 136, 2004. School of Music, Pittsburgh, PA Computer Science Department, Pittsburgh, PA attractors, cellular automata) [10] Wilson, Scott, “Spatial Swarm Granulation.” [email protected] [email protected] 5. Flocking systems (boids, swarms) [Online]. Available: 6. Vortex and other ‘wind’ motions (may not be so http://eprints.bham.ac.uk/237/1/cr1690.pdf. effective in audio) [Accessed: 07-Feb-2013]. ABSTRACT Two other developments that would reap artistic [11] D. Smalley, “Spectromorphology: explaining benefits: sound-shapes,” Organised sound, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. Music notation includes a specification of control flow, 1. A non-linear method for creating grains instead 107–126, 1997. which governs the order in which the score is read us- of the current fixed ‘hop-size with variance’. [12] V. Pulkki, “Virtual sound source positioning using ing constructs such as repeats and endings. Music theory We imagine some kind of ‘swarm’ or ‘burst’ vector base amplitude panning,” Journal of the provides only an informal description of control flow no- algorithm could be applied to the creation times Audio Engineering Society, vol. -

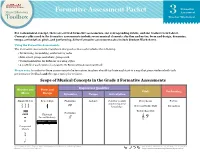

Formative Assessment Packet Formative Music Educators 3 Assessment Toolbox Teacher Worksheet

Formative Assessment Packet Formative Music Educators 3 Assessment Toolbox Teacher Worksheet For each musical concept, there are several formative assessments, one corresponding rubric, and one teacher record sheet. Concepts addressed in the formative assessments include seven musical elements: rhythm and meter, form and design, dynamics, tempo, articulation, pitch, and performing. Select formative assessments also include Student Worksheets. Using the Formative Assessments The Formative Assessments have been designed so that each includes the following: • Performing, responding, and creating tasks • Solo, small-group, and whole-group work • Varied modalities for different learning styles • A scaffold of each musical concept to its Summative Assessment task Please note: In order for these assessments to be formative, teachers should facilitate each task in a way that gives students both task performance feedback and the opportunity for revision. Scope of Musical Concepts in the Grade 3 Formative Assessments Expressive Qualities Rhythm and Form and Pitch Performing Meter Design Dynamics Tempo Articulation Simple Meters Repeat Sign Pianissimo Andante Continue to apply Steps/Leaps Posture pp and develop prior @#$ } knowledge. Notes on Treble Staff Intonation Treble/Bass Clef Fortissimo Sycore Form and Design FirstGrade 3 and Student WorkshSecondeet: 2nd Ending Endingss ff G? W 3 4 5 6 w1 2 1. 2. Ï Ï Ï & 4 Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï . Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Compound Meters P d This resource is part of Carnegie Hall’s Music Educators Toolbox (carnegiehall.org/toolbox). Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under © 2014 The Carnegie Hall Corporation http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ © Formative Music Educators Form and Design 3 Assessment Toolbox Teacher Worksheet Score Form and Design Grade 3 Student Worksheet: 2nd Endings Repeat Sign First and Second Endings 3 4 5 6 1 2 1.