Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metabolism of Contraceptive Steroids. a Thesis For

1. I fit-- 'IN VITRO ' METABOLISM OF CONTRACEPTIVE STEROIDS. A THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 1976 . FIRYAL SULTANAUkAN.MSc. THE ROYAL POSTGRADUATE MEDICAL SCHOOL, LONDON. 2. A B S T R A C T. A comparative in vitro' investigation of the effect of various substituent groups on the structurally related synthetic 19-norprogestogens (norethisterone norgestrel, lynestrenol and their esterified derivatives) in the rabbit hepatic and extrahepatic tissues is described. Using total tissue homogenates, the study indicated that various structural modifications of the progestogens resulted in compounds with varying degrees of resistance to metabolism. (The esterified derivatives were metabolised at a comparatively slower rate than the non-esterified progestogens). However, the route of metabolism was not affected by these modifications as compared to natural steroids. Amongst the extrahepatic tissues small intestine, lung and skeletal muscle tissue metabolised the progestogens but at a slower rate than in the liver. Mainly ring-A reduced metabolites were identified. In contrast to the study with total liver homogenates, in the microsomal fraction of rabbit liver ring-A reduced and hydroxylated products were identified from d-, dl- and 1-norgestrel. d-norgestrel followed the reductive and oxidative pathways equally, whereas dl- and 1-norgestrel were mainly hydroxylated. In comparison to testosterone d-, dl- and 1-norgestrel were metabolised at a slower rate. As compared to dehydroepiandrosterone and ethynyloestradiol, the rate of sulphate conjugation of the 19-norprogestogens was relatively slower in the liver. Gastrointestinal and lung tissues also sulphated these compounds. The 19-norprogestogens were conjugated at C-17, dehydroepiandrosterone at C-3 and ethynyloestradiol at both C-3 and C-17 in the liver. -

Chemistry of Pyrroles

CHEMISTRY OF PYRROLES CHEMISTRY OF PYRROLES Boris A. Trofimov Al’bina I. Mikhaleva Elena Yu Schmidt Lyubov N. Sobenina Boca Raton London New York CRC Press is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group 6000 Broken Sound Parkway NW, Suite 300 Boca Raton, FL 33487-2742 © 2015 by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC CRC Press is an imprint of Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa business No claim to original U.S. Government works Version Date: 20140815 International Standard Book Number-13: 978-1-4822-3243-1 (eBook - PDF) This book contains information obtained from authentic and highly regarded sources. Reasonable efforts have been made to publish reliable data and information, but the author and publisher cannot assume responsibility for the validity of all materials or the consequences of their use. The authors and publishers have attempted to trace the copyright holders of all material reproduced in this publication and apologize to copyright holders if permission to publish in this form has not been obtained. If any copyright material has not been acknowledged please write and let us know so we may rectify in any future reprint. Except as permitted under U.S. Copyright Law, no part of this book may be reprinted, reproduced, transmit- ted, or utilized in any form by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying, microfilming, and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the publishers. For permission to photocopy or use material electronically from this work, please access www.copyright. -

Hazardous Substances (Chemicals) Transfer Notice 2006

16551655 OF THURSDAY, 22 JUNE 2006 WELLINGTON: WEDNESDAY, 28 JUNE 2006 — ISSUE NO. 72 ENVIRONMENTAL RISK MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY HAZARDOUS SUBSTANCES (CHEMICALS) TRANSFER NOTICE 2006 PURSUANT TO THE HAZARDOUS SUBSTANCES AND NEW ORGANISMS ACT 1996 1656 NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE, No. 72 28 JUNE 2006 Hazardous Substances and New Organisms Act 1996 Hazardous Substances (Chemicals) Transfer Notice 2006 Pursuant to section 160A of the Hazardous Substances and New Organisms Act 1996 (in this notice referred to as the Act), the Environmental Risk Management Authority gives the following notice. Contents 1 Title 2 Commencement 3 Interpretation 4 Deemed assessment and approval 5 Deemed hazard classification 6 Application of controls and changes to controls 7 Other obligations and restrictions 8 Exposure limits Schedule 1 List of substances to be transferred Schedule 2 Changes to controls Schedule 3 New controls Schedule 4 Transitional controls ______________________________ 1 Title This notice is the Hazardous Substances (Chemicals) Transfer Notice 2006. 2 Commencement This notice comes into force on 1 July 2006. 3 Interpretation In this notice, unless the context otherwise requires,— (a) words and phrases have the meanings given to them in the Act and in regulations made under the Act; and (b) the following words and phrases have the following meanings: 28 JUNE 2006 NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE, No. 72 1657 manufacture has the meaning given to it in the Act, and for the avoidance of doubt includes formulation of other hazardous substances pesticide includes but -

Cumulative Cross Index to Iarc Monographs

PERSONAL HABITS AND INDOOR COMBUSTIONS volume 100 e A review of humAn cArcinogens This publication represents the views and expert opinions of an IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, which met in Lyon, 29 September-6 October 2009 LYON, FRANCE - 2012 iArc monogrAphs on the evAluAtion of cArcinogenic risks to humAns CUMULATIVE CROSS INDEX TO IARC MONOGRAPHS The volume, page and year of publication are given. References to corrigenda are given in parentheses. A A-α-C .............................................................40, 245 (1986); Suppl. 7, 56 (1987) Acenaphthene ........................................................................92, 35 (2010) Acepyrene ............................................................................92, 35 (2010) Acetaldehyde ........................36, 101 (1985) (corr. 42, 263); Suppl. 7, 77 (1987); 71, 319 (1999) Acetaldehyde associated with the consumption of alcoholic beverages ..............100E, 377 (2012) Acetaldehyde formylmethylhydrazone (see Gyromitrin) Acetamide .................................... 7, 197 (1974); Suppl. 7, 56, 389 (1987); 71, 1211 (1999) Acetaminophen (see Paracetamol) Aciclovir ..............................................................................76, 47 (2000) Acid mists (see Sulfuric acid and other strong inorganic acids, occupational exposures to mists and vapours from) Acridine orange ...................................................16, 145 (1978); Suppl. 7, 56 (1987) Acriflavinium chloride ..............................................13, -

G.P. Ellis (3).Pdf

Progress in Medicinal Chemistry 16 This Page Intentionally Left Blank Progress in Medicinal Chemistry 16 Edited by G.P. ELLIS, D.SC., PH.D.,F.R.I.C. Department of Chemistry, University of Wales Institute of Science and Technology, King Edward VII Avenue, Card& CFl 3NU and G.B. WEST, B.PHARM., D.SC., PH.D., F.I.BIOL. Department of Paramedical Sciences, North East London Polytechnic, Romford Road, London El5 4LZ 1979 NORTH-HOLLAND PUBLISHING COMPANY AMSTERDAM.NEW YORK.OXFORD 0Elsevier/North-Holland Biomedical Press - 1979 AN rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system. or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic. mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN for the series: 0 7204 7400 0 ISBN for this volume: 0 7204 0667 6 PUBLISHERS : Elsevier North-Holland Biomedical Press 335 Jan van Galenstraat, P.O. Box 21 1 Amsterdam, The Netherlands SOLE DISTRIBUTORS FOR THE U.S.A. AND CANADA: Elsevier/North-Holland Inc. 52 Vanderbilt Avenue New York, N.Y. 10017, U.S.A. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA Main entry under title: Progress in medicinal chemistry. London, Butterworths, 1961-1973 (Vols. 1-9). Amsterdam, North-Holland Publishing Co., 1974- (Vols. 10- ). Editors: 1961- G.P. Ellis and G.B. West. Includes bibliography. 1. Pharmacology-Collected works. 2. Chemistry, Medical and Pharmaceutical. I. Ellis, Gwynn Pennant, ed. 11. West, Geoffrey Buckle, 1961- ed. 111. Title: Medicinal chemistry. RS402.P78 615'.19 62-27 12 Photosetting by Thornson Press (India) Limited, New Delhi Printed in The Netherlands Preface We have pleasure in presenting five reviews in this volume. -

Book of Abstracts

BOOK OF ABSTRACTS Book of abstracts 7ENQO Sociedade Portuguesa de Química 16th-18th July 2007 Lisboa, Portugal Email: [email protected] URL: www.dq.fct.unl.pt/7enqo Editor: Sociedade Portuguesa de Química Editorial Coordinator: Abel Vieira Eurico Cabrita Maria Manuel Marques ISBN: 978-989-8124-00-5 7th Portuguese National Meeting of Organic Chemistry 7th Portuguese National Meeting of Organic Chemistry 7th Portuguese National Meeting of Organic Chemistry Welcome It is normal for the organisers of a meeting to express their hopes at the outset that all will go well, and to make a few general statements about how significant the gathering will be. The National Meetings of Organic Chemistry – best known as ENQOs, have in the past created in the life of the Division of Organic Chemistry of the Portuguese Chemical Society (SPQ) the opportunity for its members to meet every two years, exchange views and discuss their scientific achievements. Hopefully the 7ENQO will achieve the outstanding success of previous gatherings. This year, during the last day devoted to the 1st Portuguese-French Meeting, colleagues from France will meet with Portuguese organic chemists to pave the way for a closer scientific collaboration in the future. Indeed such is the way science, in general, and chemistry, in particular, will have to move if our European Nations are to remain scientifically relevant, in view of the speed of progress and discovery occurring in other blocks around the world. Every journey is made of small steps. Let us hope that the 7ENQO will represent yet another step in the already long life of SPQ and an occasion for gauging the progress of our science and enjoying our city. -

Spectra Library Index Ichem/SDBS Raman Library

Ichem / SDBS Raman スタンダードライブラリー 株式会社 エス・ティ・ジャパン S p e c t r a L i b r a r y I n d e x (Ver. 40) Ichem / SDBS Raman Library ライブラリー名:ラマンスタンダードライブラリー 商品番号:60001-40 株式会社 エス・ティ・ジャパン 〒103-0014 東京都中央区日本橋蛎殻町 1-14-10 Tel: 03-3666-2561 Fax:03-3666-2658 http://www.stjapan.co.jp 1 【販売代理店】(株)テクノサイエンス Tel:043-206-0155 Fax:043-206-0188 https://www.techno-lab-co.jp/ Ichem / SDBS Raman スタンダードライブラリー 株式会社 エス・ティ・ジャパン ((1,2-DIETHYLETHYLENE)BIS(P-PHENYLENE))DIACETATE ((2-(3-BENZYLSULFONYL-4-METHYLCYCLOHEXYL)PROPYL)SULFONYLMETHYL)BENZENE ((2,4,6-TRIOXOHEXAHYDRO-5-PYRIMIDINYL)IMINO)DIACETIC ACID ((2-CARBOXYETHYL)IMINO)DIACETIC ACID ((2-HYDROXYETHYL)IMINO)DIACETIC ACID ((2-NITROBENZYL)IMINO)DIACETIC ACID ((2-SULFOETHYL)IMINO)DIACETIC ACID ((3-(1-BROMO-1-METHYLETHYL)-7-OXO-1,3,5-CYCLOHEPTATRIEN-1-YL)OXY)DIFLUOROBORANE ((N-BENZYLOXYCARBONYL-L-ISOLEUCYL)-L-PROLYL-L-PHENYLALANYL)-N(OMEGA)-NITRO-L-ARGININE 4-NITROBENZYL ESTER (-)-2-AMINO-1-BUTANOL (-)-2-AMINO-6-MERCAPTOPURINE RIBOSIDE (-)-6,8-P-MENTHADIEN-2-OL (-)-DIACETYL-L-TARTARIC ACID (-)-DIBENZOYL-L-TARTARIC ACID (-)-DI-P-ANISOYL-L-TARTARIC ACID (-)-DI-P-TOLUOYL-L-TARTARIC ACID (-)-KAURENE (-)-MENTHOL (-)-MYRTENOL (-)-N,N,N',N'-TETRAMETHYL-D-TARTARDIAMIDE (-)-N,N'-DIBENZYL-D-TARTRAMIDE (+)-1,3,3-TRIMETHYLNORBORNANE-2-ONE (+)-2-(2,4,5,7-TETRANITRO-9-FLUORENYLIDENEAMINOOXY)PROPIONIC ACID (+)-2-AMINO-1-BUTANOL (+)-2-PINENE (+)-3,9-DIBROMOCAMPHOR (+)-3-CARENE (+)-5-BROMO-2'-DEOXYURIDINE (+)-AMMONIUM 3-BROMO-8-CAMPHORSULFONATE (+)-CAMPHOR (+)-CAMPHOR OXIME (+)-CAMPHORIC ACID (+)-CATECHIN (+)-DI-P-ANISOYL-D-TARTARIC -

Agents Classified by the IARC Monographs, Volumes 1–123

Agents Classified by the IARC Monographs, Volumes 1–123 1 CAS No. Agent Group0B Volume Year 026148-68-5 A-alpha-C (2-Amino-9H-pyrido[2,3-b]indole) 2B 40, Sup 7 1987 000083-32-9 Acenaphthene 3 92 2010 025732-74-5 Acepyrene (3,4-dihydrocyclopenta[cd]pyrene) 3 92 2010 000075-07-0 Acetaldehyde 2B 36, Sup 7, 71 1999 000075-07-0 Acetaldehyde associated with consumption of alcoholic 1 100E 2012 beverages 000060-35-5 Acetamide 2B 7, Sup 7, 71 1999 000103-90-2 Acetaminophen (see Paracetamol) Acheson process, occupational exposure associated with 1 111 2017 059277-89-3 Aciclovir 3 76 2000 Acid mists, strong inorganic 1 54, 100F 2012 000494-38-2 Acridine orange 3 16, Sup 7 1987 008018-07-3 Acriflavinium chloride 3 13, Sup 7 1987 000107-02-8 Acrolein 3 63, Sup 7 1995 000079-06-1 Acrylamide 2A 60, Sup 7 1994 (NB: Overall evaluation upgraded to Group 2A with supporting evidence from other relevant data) 000079-10-7 Acrylic acid 3 19, Sup 7, 71 1999 Acrylic fibres 3 19, Sup 7 1987 000107-13-1 Acrylonitrile 2B 71 1999 Acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene copolymers 3 19, Sup 7 1987 000050-76-0 Actinomycin D 3 10, Sup 7 1987 023214-92-8 Adriamycin 2A 10, Sup 7 1987 (NB: Overall evaluation upgraded to Group 2A with supporting evidence from other relevant data) 003688-53-7 AF-2 [2-(2-Furyl)-3-(5-nitro-2-furyl)acrylamide] 2B 31, Sup 7 1987 001402-68-2 Aflatoxins (B1, B2, G1, G2, M1) 1 Sup 7, 56, 2012 82, 100F, 002757-90-6 Agaritine 3 31, Sup 7 1987 Alcoholic beverages 1 44, 96, 100E 2012 000116-06-3 Aldicarb 3 53 1991 000309-00-2 Aldrin (see Dieldrin, and aldrin metabolized to dieldrin) Aloe vera, whole leaf extract 2B 108 2016 000107-05-1 Allyl chloride 3 36, Sup 7, 71 1999 000057-06-7 Allyl isothiocyanate 3 73, Sup 7 1999 002835-39-4 Allyl isovalerate 3 36, Sup 7, 71 1999 Alpha particles (see Radionuclides) Aluminium production 1 34, Sup 7, 2012 92, 100F 000915-67-3 Amaranth 3 8, Sup 7 1987 1 Agents Classified by the IARC Monographs, Volumes 1–123 1 CAS No. -

AB 2588 EICG Appendix a Combined List of Substances

AB 2588 EICG Regulation Appendix A - PRELIMINARY DRAFT PROPOSAL FOR PUBLIC REVIEW Overview of Proposed Additions to AB2588's Emission Inventory Criteria and Guidelines Regulation, Appendix A CARB requirements, by statute (Health & Safety Code Section 44300) The AB 2588 Air Toxics “Hot Spots” Program (Statute; Health and Safety Code (H&SC) Sections 44300) requires CARB to compile and maintain a list of substances for assessing toxic air pollutants. In our assessment, we consider specific international, national, state, and other lists of chemicals explicitly referenced in the Statute, as well as under our own CARB authority. There are seven sources from which the chemical substances are required to be considered for inclusion on the Hot Spots list. (1) CARB’s Toxic Air Contaminants (TACs) (2) US EPA Hazardous Air Pollutants (HAPs) (3) International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) (4) Proposition 65 (5) National Toxicology Program (NTP) (6) Hazard Evaluation System and Information Service (HESIS) (7) Explicit provision of CARB authority By statute, CARB is required to list all of the chemical substances found in the list above in Appendix A of the EICG, unless the substance meets the following criteria: (1) No evidence exists that it has been detected in the air (2) The substance is not manufactured or used in California CARB has divided the list into three appendices as described here: A-I are substances for which emissions are required to be quantified A-II are substances for which production, use, or other presence must be reported A-III are substances which need not be reported unless manufactured by the facility Additional information Over the past decade, many new chemical substances have emerged. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2009/0118236A1 Erion Et Al

US 200901 18236A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2009/0118236A1 Erion et al. (43) Pub. Date: May 7, 2009 (54) NOVEL PHOSPHORUS-CONTAINING Publication Classification THYROMMETCS (51) Int. Cl. (76) Inventors: Mark D. Erion, Del Mar, CA (US); gt. 5% CR Hongjian Jiang, San Diego, CA A6II 3/662 CR (US); Serge H. Boyer, San Diego, ( .01) CA (US) C07F 9/59 (2006.01) A6IP5/4 (2006.01) Correspondence Address: 9."66 :08: STERNE KESSLER GOLDSTEIN & FOX P.L. L.C 9 9 C07F 9/58 (2006.01) 1100 NEW YORKAVENUE, N.W. C07F 9/38 (2006.01) WASHINGTON, DC 20005 (US) (52) U.S. Cl. ............. 514/89;568/15: 514/130; 514/119; 564/15: 514/114: 546/22:568/12: 514/110; (21) Appl. No.: 10/580,134 436/5O1 (22) PCT Filed: Nov. 19, 2004 (57) ABSTRACT The present invention relates to compounds of phosphonic (86). PCT No.: PCT/USO4/39024 acid containing T3 mimetics, Stereoisomers, pharmaceuti S371 (c)(1) cally acceptable salts, co-crystals, and prodrugs thereof and (2), (4).te: May 30, 2007 pharmaceutically acceptable salts and co-crystals of the pro s 9 drugs, as well as their preparation and uses for preventing and/or treating metabolic diseases such as obesity, NASH, Related U.S. Application Data hypercholesterolemia and hyperlipidemia, as well as associ (60) Provisional application No. 60/523,830, filed on Nov. ated conditions such as atherosclerosis, coronary heart dis 19, 2003, provisional application No. 60/598.524, ease, impaired glucose tolerance, metabolic syndromex and filed on Aug. -

Industrial Chemicals, Ashfords Dictionary, Chemical Name Index

2 Chemical name index A A ACA 4-AA ACA AA ACAC AA acamprosate calcium AAA acarbose AABA ACB AADMC 7-ACCA AAEM ACE AAMX acebutolol AAOA aceclidine AAOC aceclofenac AAOT acemetacin AAPP acenaphthene AAPT acenocoumarol 4-ABA acephate ABA acepromazine abacavir acequinocyl ABAH acesulfame-K abamectin acetaldehyde ABFA acetaldehyde ethyl phenethyl diacetal ABL acetaldehyde oxime ABPA acetaldehyde n-propyl phenethyl diacetal ABS acetaldoxime ABS acetal resins O-ABTF acetal resins P-ABTF acetamide ACN acetamidine hydrochloride 7-ACA 5-acetamido-2-aminobenzenesulfonic acid 7-ANCA 6-acetamido-2-aminophenol-4-sulfonic acid Name Index: Ashford’s Dictionary of Industrial Chemicals 3-acetamidoaniline 3-acetamidoaniline acetic acid, s-butyl ester 4-acetamidoaniline acetic acid, calcium salt p-acetamidoanisole acetic acid, chromium salt 4-acetamidobenzenesulfonyl chloride acetic acid, cinnamyl ester 2-acetamidocinnamic acid acetic acid, citronellyl ester 3-acetamido-2-hydroxyaniline-5-sulfonic acid acetic acid, cobalt salt 1-acetamido-7-hydroxynaphthalene acetic acid, decahydro-β-naphthyl ester 8-acetamido-1-hydroxynaphthalene-3,6-disulfonic acid acetic acid, dicyclopentenyl ester 1-acetamido-7-naphthol acetic acid, diethylene glycol monobutyl ether ester 4-acetamidonitrobenzene acetic acid, 2-ethoxyethyl ester p-acetamidophenol acetic acid, ethoxypropyl ester 3-acetamidopropylsulfonic acid, calcium salt acetic acid, ethyl diglycol ester 5-acetamido-2,4,6-triiodo-N-methylisophthalamic acid acetic acid, ethylene glycol diester 4-acetamido-2-ethoxybenzoic -

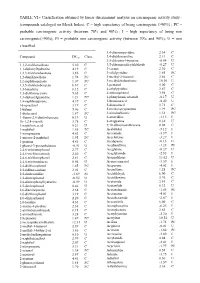

TABLE VI.- Classification Obtained by Linear Discriminant Analysis on Carcinogenic Activity Study : (Compounds Cataloged on Merck Index)

TABLE VI.- Classification obtained by linear discriminant analysis on carcinogenic activity study : (compounds cataloged on Merck Index). C = high expectancy of being carcinogenic (>90%) ; PC = probable carcinogenic activity (between 70% and 90%) ; I = high expectancy of being non carcinogenic(>90%); PI = probable non carcinogenic activity (between 70% and 90%); U = non classified. 3,4-diaminopyridine 2.34 C Compound DFcarc Class. 3,4-dichloroaniline 2.13 C 3,5-dibromo-l-tyrosine -0.54 U 1,1,2-trichloroethane 5.30 C 3,5-dibromosalicylaldehyde -0.27 U 1,1-diphenylhydrazine 4.19 C 3-carene 2.30 C 1,2,3-trichlorobenzene 3.86 C 3-ethylpyridine 1.85 PC 1,2-dianilinoethane 1.74 PC 3-methyl-2-butanol 3.66 C 1,2-naphthoquinone 1.07 PC 3-methylcholanthrene 10.30 U 1,3,5-trichlorobenzene 6.67 C 3-pentanol 5.00 C 1,3-butadiene 8.12 C 4-ethylpyridine 2.87 C 1,3-dichloroacetone 5.65 C 4-nitrosophenol 3.98 C 1,3-diphenylguanidine 1.21 PC 4-phenylsemicarbazide -0.17 U 1,4-naphthoquinone 4.37 C 5-bromouracil -0.42 U 16-epiestriol 3.19 C 5-diazouracil 3.71 C 1-butene 5.06 C 5-methoxytryptamine 1.99 PC 1-dodecanol 1.87 PC 5-nitrobarbituric 1.51 PC 1-fluoro-2,4-dinitrobenzene 0.19 U 6-azauridine -3.15 I 1h-1,2,4-triazole 3.75 C 8-azaguanine 0.30 U 1-naphthoic,acid 0.21 U 9,10-dibromoanthracene 8.02 C 1-naphthol 1.65 PC Acebutolol -5.12 I 1-nitropropane 4.63 C Acecainide -3.39 I 1-nitroso-2-naphthol 1.95 PC Aceclofenac -3.27 I 1-pentene 4.41 C Acedapsone -0.13 U 1-phenyl-3-pyrazolidinone -0.91 U Acediasulfone -1.23 PI 2,4,6-tribromophenol 2.77 C Aceglatone