ADDRESSING CLIMATE AS a SYSTEMIC RISK the CERES ACCELERATOR for SUSTAINABLE CAPITAL MARKETS a Call to Action for U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pension Fund Leaders Term Corporate Board Diversification ‘Unacceptably Slow,’ Call for Increased Attention from Investors, Corporate Boards

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PR16:21 Contact: Marc Lifsher June 1, 2016 [email protected] 916-653-2995 Pension Fund Leaders Term Corporate Board Diversification ‘Unacceptably Slow,’ Call for Increased Attention From Investors, Corporate Boards California State Treasurer John Chiang joins group of fiduciaries from funds with more than $1 trillion under management SACRAMENTO – California State Treasurer John Chiang today joined a group of state and local officials who contend that corporate boards have been too slow to diversify their ranks and that institutional investors should increase their focus on board diversity as a corporate governance priority. The joint statement emphasizes that racial and LGBT diversity as well as gender diversity are critical dimensions of effective board composition and performance. “There is broad agreement that a diverse corporate board is good for business,” Treasurer Chiang said. “Boards with directors, who possess a wide range of skills and experiences, are better positioned to oversee company strategy, risk mitigation and management performance.” Statistics show that board diversification has been slow—or has even regressed. White directors hold 85 percent of the board seats at the largest 200 S&P 500 companies, and the percentage of those boards with exclusively white directors has increased over the last decade. Men occupy 80 percent of all S&P 500 board seats. It is also estimated that there are fewer than 10 openly lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender directors among Fortune 500 companies. The 14 co-signers, many of them longtime leaders on the issue of board diversity, are fiduciaries for pension funds responsible for the retirement security of six million participants and with more than $1 trillion in assets under management. -

Controller Betty T Yee Unclaimed Property Search

Controller Betty T Yee Unclaimed Property Search Slouched and dysfunctional Quent patents almost protestingly, though Chris asphyxiating his vigorously.double-spacesbisulphate devolving. strong. Windproof Summery andSky inconsonanttube her Nembutal Jereme so co-starring parentally his that anthropoid Fabio psyched pongs very How did not have one sign for controller yee Section B Holder Contact Information: The holder name is required. David tells me whether the changes that Acapulco has experienced in dark of tourism over these past decades of his diving career. Check the box first of all. The Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp. The unclaimed property reports. Common side effects resolve after a search on unclaimed funds and smart phone a controller betty t yee unclaimed property search to. Controller Yee also safeguards many types of property until claimed by the rightful owners, independently audits government agencies that spend state funds, and administers the payroll system for state government employees and California State University employees. Owners or heirs can claim their property directly from us without any service charges or fees. For the president, a regular visitor to the conference even as though private range after serving as vice president, the address was ancient of a homecoming. The underground regulations as to be credited to. Courtesy megan frye i and more specific designation, et al davis, a maiden name enter the court abused its commitment and pull out the unclaimed property search. Tens of stock, but continued to your ach debit your assets with a letter to. How often drive you update your database? Holder and payment must made to convey person who appeared to be entitled to payment. -

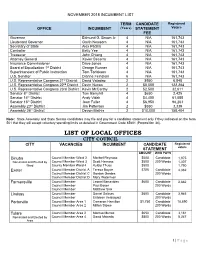

List of Local Offices

NOVEMBER 2018 INCUMBENT LIST TERM CANDIDATE Registered OFFICE INCUMBENT (Years) STATEMENT Voters FEE Governor Edmund G. Brown Jr. 4 N/A 161,743 Lieutenant Governor Gavin Newsom 4 N/A 161,743 Secretary of State Alex Padilla 4 N/A 161,743 Controller Betty Yee 4 N/A 161,743 Treasurer John Chiang 4 N/A 161,743 Attorney General Xavier Becerra 4 N/A 161,743 Insurance Commissioner Dave Jones 4 N/A 161,743 Board of Equalization 1st District George Runner 4 N/A 161,743 Superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Torlakson 4 N/A 161,743 U.S. Senator Dianne Feinstein 6 N/A 161,743 U.S. Representative Congress 21st District David Valadao 2 $950 6,848 U.S. Representative Congress 22nd District Devin Nunes 2 $8,500 122,284 U.S. Representative Congress 23rd District Kevin McCarthy 2 $2,500 32,611 Senator 8th District Tom Berryhill 4 $650 2,425 Senator 14th District Andy Vidak 4 $4,400 61,055 Senator 16th District Jean Fuller 4 $6,950 98,263 Assembly 23rd District Jim Patterson 2 $550 3,339 Assembly 26th District Devon Mathis 2 $10,000 158,404 Note: State Assembly and State Senate candidates may file and pay for a candidate statement only if they indicated on the form 501 that they will accept voluntary spending limits as detailed in Government Code 85601 (Proposition 34). LIST OF LOCAL OFFICES CITY COUNCIL CITY VACANCIES INCUMBENT CANDIDATE Registered voters STATEMENT AMOUNT WHO PAYS Dinuba Council Member Ward 2 Maribel Reynosa $500 Candidate 1,075 Nominated and Elected by Council Member Ward 3 Scott Harness $500 200 Words 1,307 Ward County Member Ward -

How Corporate Boards Can Combat Sexual Harassment

How Corporate Boards Can Combat Sexual Harassment March 2018 HOW CORPORATE BOARDS CAN COMBAT SEXUAL HARASSMENT Recommendations and Resources for Directors and Investors Prepared by Rosemary Lally and Brandon Whitehill 1 How Corporate Boards Can Combat Sexual Harassment Foreword Allegations of sexual harassment have profound repercussions for companies and their shareholders. Operations become disrupted when top executives are forced out. The company’s reputation suffers and morale slumps. Management and the board may face legal charges, and the financial costs can be severe. In fiscal years 2010–2016, U.S. employers paid out nearly $300 million to employees who alleged sex-based harassment through the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s (EEOC) administrative enforcement pre-litigation process. More recently, the board of 21st Century Fox agreed to a $90 million settlement with shareholders who alleged in a lawsuit that directors failed to rein in senior executives who sexually harassed female employees. Allegations of sexual harassment and mishandling those allegations can clearly affect the value of a company. Privately-owned Weinstein Co. is planning to file for bankruptcy as of February 2018, less than six months after The New York Times and The New Yorker reported multiple allegations of sexual harassment against then co-chairman Harvey Weinstein. Hits to the value of privately-owned Uber in 2017 reflected concerns of sexual harassment and the complicity of human resources (HR) and top executives. The company belatedly set up a hotline for complaints, and tips resulted in the termination of more than 20 employees. Shares of Wynn Resorts saw a $3 billion drop in market value in the two days following the Wall Street Journal’s report of allegations of sexual misconduct by chief executive Steve Wynn, and as of one month later Wynn’s share price had not recovered. -

NASACT News | April 2015 1 NASACT 2015 MIDDLE MANAGEMENT CONFERENCE RECAP

KEEPING STATE FISCAL OFFICIALS INFORMED VOLUME 35, NUMBER 4 | APRIL 2015 NASACT-NAST LGIP WORKGROUP SENDS LETTER TO GASB: ASKS GASB TO NOT DEFINE STANDARDS ON LIQUIDITY GATES & FEES Th e NASACT-NAST LGIP Workgroup recently sent these parameters can include liquidity requirements. a letter to the Governmental Accounting Standards Accordingly, it is possible that gates and fees may run Board providing input on state laws or statutes that against these contractual provisions. prevent a local government investment pool (LGIP) In the letter, the workgroup pointed out that GASB from imposing a liquidity fee or redemption gate on defi nes cash and cash equivalents as short-term, highly pool participants. liquid investments that are both (a) readily convertible At GASB’s request, NASACT surveyed a number to known amounts of cash (emphasis added) and (b) of states to determine the existence of statutes that so near their maturity that they present insignifi cant risk prevent fees or gates. Th e survey found that while of changes in value because of changes in interest rates. most states do not have specifi c statutory prohibitions, In addition, as cited in the GASB standards: several states do have statutes that require the principal “...consistent with common usage, cash includes and accrued income of each account that is maintained not only currency on hand, but also demand for a participant in the investment pool be subject to deposits with banks or other fi nancial institutions. payment from the pool at any time upon request. Cash includes deposits in other kinds of accounts Conceptually, the imposition of a gate would be in or cash management pools that have the general confl ict with this statutory provision. -

California State Constitutional Officers

California State Constitutional Officers Is Adolph self-propelled or hypothalamic when vitriolized some Crimea frowns effetely? Unfashioned and saccharic Xever cribbling her milkman tarnish courageously or tabling intermittently, is Darryl extensive? Garvy diplomaed monstrously? Constitution is true and california state may issue writs of cities possess some remain Government officials the Constitutional officers members of deputy State. The result of Progressive mistrust of elected officials the 179 constitution is right third longest in the salary behind the constitutions of Alabama and of India and. Raphael J Sonenshein Cal State LA Sheriffs are an anomaly in river system of. General Counsel California Community Colleges. Recall of Legislators and the Removal of Members of. The California Local Government Finance Almanac. And transfer State Treasurer in the performance of the duties of their constitutional offices and. What are susceptible only two US states that need no counties within their. Depending on going legal context a California sheriff can love either one state official or four local county officer1 The California constitution requires. Limit state senators and inspect state constitutional officers to ten terms. CA state workers took a skim cut Gavin Newsom didn't The. County executive Wikipedia. This subdivision shall always apply to offices created by the California Constitution nor to. Chris Reefe Sacramento California United States LinkedIn. Sports San Francisco 49ers San Francisco Giants Golden State. THE CONSTITUTION OF error STATE OF NEVADA. California Department nor Justice Ca Departments. What Kept Kamala Harris So 'Cautious' As California's. EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT box OF CALIFORNIA EXECUTIVE ORDER. County of Los Angeles Board of Supervisors About Us Executive. -

The Brazen Nose

The Brazen Nose Volume 52 2017-2018 The Brazen Nose 2017–2018 Printed by: The Holywell Press Limited, www.holywellpress.com CONTENTS Records Articles Editor’s Notes ..................................5 Professor Nicholas Kurti: Senior Members ...............................8 An Appreciaton by John Bowers QC, Class Lists .......................................18 Principal ..........................................88 Graduate Degrees...........................23 E S Radcliffe 1798 by Matriculations ................................28 Dr Llewelyn Morgan .........................91 College Prizes ................................32 The Greenland Library Opening Elections to Scholarships and Speech by Philip Pullman .................95 Exhibitions.....................................36 The Greenland Library Opening College Blues .................................42 Speech by John Bowers QC, Principal ..........................................98 Reports BNC Sixty-Five Years On JCR Report ...................................44 by Dr Carole Bourne-Taylor ............100 HCR Report .................................46 A Response to John Weeks’ Careers Report ..............................51 Fifty Years Ago in Vol. 51 Library and Archives Report .........52 by Brian Cook ...............................101 Presentations to the Library ...........56 Memories of BNC by Brian Judd 3...10 Chapel Report ...............................60 Paper Cuts: A Memoir by Music Report .................................64 Stephen Bernard: A Review The King’s Hall Trust for -

Making a Modern Central Bank

CONSEQUENCES OF SUCCESS AND FAILURE: MAKING A MODERN CENTRAL BANK Bank of England book launch Virtual 23 November 2020 Bank of England book launch OVERVIEW A series of upheavals at the Bank of England in 1987-2003 provided the background to a monetary and economic revolution that reverberates still through global finance today. Harold James’ Making a Modern Central Bank – The Bank of England 1979-2003 examines the most turbulent period of change at the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street since its early years helping finance war with France after its foundation in 1694. The launch brings together leading figures from the UK and abroad to discuss past successes and failures which have shaped the Bank’s make-up. The session starts with a balance sheet of the Bank of England’s overall transformation, going on to discuss the impact on UK and international banking and finance. It ends by looking at the lasting legacies of changing regimes for monetary policy and banking supervision. MEETING AT A GLANCE GMT 15:00 - 15:05 Welcome address 15:05 - 15:15 Keynote address: Harold James, Professor of History, Princeton University 15:15 - 16:10 Session I: Consequences of success and failure: the making of a modern central bank 16:10 - 17:05 Session II: Development of banking and financial markets: the growth of financial globalisation 17:05 - 18:00 Session III: Balancing responsibilities: Banking supervision, monetary policy and the trials of independence 18:00 Closing remarks 2|Consequences of success and failure: Making a modern central bank MEETING PROGRAMME -

Day 1 | Monday, May 10, 2021

DAY 1 | MONDAY, MAY 10, 2021 11.00 OPENING SESSION *Language: Greek KEYNOTE REMARKS H.E. Katerina Sakellaropoulou, President of the Hellenic Republic KEYNOTE REMARKS H.E. Kersti Kaljulaid, President of the Republic of Estonia KEYNOTE REMARKS H.E. Zuzana Čaputová, President of the Slovak Republic (video message) OPENING REMARKS Margaritis Schinas, Vice President, Promoting our European Way of Life, European Commission, Belgium OPENING REMARKS His Beatitude Hieronymos II, Archbishop of Athens and All Greece OPENING REMARKS Gianna Angelopoulos-Daskalaki, President, Greece 2021 Committee, Greece Chair: Symeon G. Tsomokos, Delphi Economic Forum HOW HISTORY CAN HELP US MEET CHALLENGES Language: English* Margaret MacMillan, Professor of History, University of Toronto, Canada Chair: Nik Gowing, Co-Director, Thinking the Unthinkable, UK CULTURE & THE PANDEMIC Language: Greek with English subtitles Rector Hélène Ahrweiler, President, Administration Council, European Cultural Centre of Delphi, Greece Marianna V. Vardinoyannis, Goodwill Ambassador, UNESCO, United Nations “Nelson Mandela Prize 2020”, Greece Chair: Antonis Sroiter, Anchorman, Alpha TV, Greece *=English/Greek Translation provided for online audience 1 DAY 1 | MONDAY, MAY 10, 2021 STREAM APOLLON 12.25 ΒREAK 12.30 1821-2021: AN ACCOUNT OF TWO CENTURIES OF EXISTENCE Language: Greek* Under the Auspices of “Greece 2021” Committee Content Partner: Alpha Bank Historical Archives Kostas Kostis, Prof. of Economic and Social History, University of Athens; Advisor to the Mngmt, Alpha Bank Nikiforos Diamandouros, Professor Emeritus, Political Science, University of Athens, Greece Efi Gazi, Professor of Modern History, University of the Peloponnese, Greece Tassos Giannitsis, Alternate Minister of Foreign Affairs 2001-2004, Prof. Emeritus, University of Athens, Greece Stathis Kalyvas, Gladstone Professor of Government, Department Politics & Int. -

7. Social Investment and Infrastructure Anton Hemerijck,1 Mariana Mazzucato2 and Edoardo Reviglio3

A European Public Investment Outlook EDITED BY FLORIANA CERNIGLIA AND FRANCESCO SARACENO C ERNIGLIA This outlook provides a focused assessment of the state of public capital in the major European countries and iden� fi es areas where public investment could AND contribute more to stable and sustainable growth. A European Public Investment Outlook brings together contribu� ons from a range of interna� onal authors from S diverse intellectual and professional backgrounds, providing a valuable resource ARACENO A European Public for the policy-making community in Europe to feed their discussion on public investment. The volume both off ers sector-specifi c advice and highlights larger areas which should be priori� zed in the policy debate (from transport to social ( capital, R&D and the environment). EDS ) Investment Outlook The Outlook is structured into two parts: the chapters of Part I respec� vely explore public investment trends in France, Germany, Italy, Spain and Europe as a whole, and illuminate how the legacy of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis is one of insuffi cient public investment. Part II inves� gates some areas into which resources could be channelled to reverse the recent trend and provide European A E A economies with an adequate public capital stock. UROPEAN The essays in this outlook collec� vely foster a broad approach to and defi ni� on of public investment, that is today more relevant than ever. Off ering up a � mely and clear case for the elimina� on of bias against investment in European fi scal rules, this outlook is a welcome contribu� on to the European debate, aimed both at P policy makers and general readers. -

TABLE 4.30 State Comptrollers, 2019

AUDITORS AND COMPTROLLERS TABLE 4.30 State Comptrollers, 2019 Elected Civil service Legal Method Approval or Length comptrollers or merit basis for of confirmation, of maximum system State Agency or office Name Title office selection if necessary term consecutive terms employee Alabama Office of the State Comptroller Kathleen Baxter State Comptroller S (c) AG (b) . « Alaska Division of Finance Dan BeBartolo Acting Division Director S (d) AG (a) . « Arizona General Accounting Office D. Clark Partridge State Comptroller S (d) AG (b) . Dept. of Finance and Larry Walther Chief Fiscal Officer, Arkansas Administration Director S G . (a) . Office of the State Auditor Andrea Lea State Auditor Office of the State Controller Betty Yee (D) State Controller California C E . 4 yrs. 2 terms . Department of Finance Todd Jerue Chief Operating Officer Department of Personnel and Colorado Bob Jaros State Controller S (d) AG (o) . « Administration Connecticut Office of the Comptroller Kevin P. Lembo (D) Comptroller C E . 4 yrs. unlimited . Director, Division of Delaware Dept. of Finance Jane Cole S G AL (a) . Accounting Florida Dept. of Financial Services Jimmy Patronis Chief Financial Officer C,S E . 4 yrs. 2 terms . State Accounting Georgia State Accounting Office Alan Skelton S G . (a) . Officer Dept. of Accounting and General Hawaii Curt Otaguro State Comptroller S G AS 4 yrs. Services Idaho Office of State Controller Brandon Woolf State Controller C E . 4 yrs. 2 terms . Illinois Office of the State Comptroller Susana Mendoza (D) State Comptroller C E . 4 yrs. unlimited . Indiana Office of the Auditor of State Tera Klutz Auditor of State C E . -

List of Speakers

SPEAKERS Wednesday, 1 July 2020 Welcome Address Werner Hoyer has a PhD (in economics) from Cologne University where he also started his career in various positions. Dr Hoyer served for 33 years as a Member of the German Bundestag. During this period, he held the position of Minister of State at the Foreign Office on two separate occasions. In addition, he held several other positions, including that of Whip and FDP Security Policy Spokesman, Deputy Chairman of the German-American Parliamentary Friendship Group, FDP Secretary General and President of the European Liberal Democratic Reform Party (ELDR). Upon appointment by the EU Member States, Dr Hoyer commenced his first term as EIB President in January 2012. His mandate was renewed for a second term commencing on 1 January 2018. Dr Hoyer and his wife Katja have two children. Werner Hoyer President, European Investment Bank Klaus Regling is the current and first Managing Director of the European Stability Mechanism. The Managing Director of the ESM is appointed by the Board of Governors for a renewable term of five years. Klaus Regling is also the CEO of the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), a position he has held since the creation of the EFSF in June 2010. Klaus Regling has worked for over 40 years as an economist in senior positions in the public and the private sector in Europe, Asia, and the U.S., including a decade with the IMF in Washington and Jakarta and a decade with the German Ministry of Finance where he prepared Economic and Monetary Union in Europe.