Monitoring Food Security in Countries with Conflict Situations a Joint FAO/WFP Update for the Members of the United Nations Security Council

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of Pibor County, South Sudan from the Perspective of Displaced People

Researching livelihoods and services affected by conflict Livelihoods, access to services and perceptions of governance: An analysis of Pibor county, South Sudan from the perspective of displaced people Working Paper 23 Martina Santschi, Leben Moro, Philip Dau, Rachel Gordon and Daniel Maxwell September 2014 About us Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium (SLRC) aims to generate a stronger evidence base on how people make a living, educate their children, deal with illness and access other basic services in conflict-affected situations (CAS). Providing better access to basic services, social protection and support to livelihoods matters for the human welfare of people affected by conflict, the achievement of development targets such as the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and international efforts at peace- and state-building. At the centre of SLRC’s research are three core themes, developed over the course of an intensive one- year inception phase: . State legitimacy: experiences, perceptions and expectations of the state and local governance in conflict-affected situations . State capacity: building effective states that deliver services and social protection in conflict- affected situations . Livelihood trajectories and economic activity under conflict The Overseas Development Institute (ODI) is the lead organisation. SLRC partners include the Centre for Poverty Analysis (CEPA) in Sri Lanka, Feinstein International Center (FIC, Tufts University), the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU), the Sustainable Development Policy -

The Greater Pibor Administrative Area

35 Real but Fragile: The Greater Pibor Administrative Area By Claudio Todisco Copyright Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva 2015 First published in March 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organi- zation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Publications Manager, Small Arms Survey, at the address below. Small Arms Survey Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies Maison de la Paix, Chemin Eugène-Rigot 2E, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Series editor: Emile LeBrun Copy-edited by Alex Potter ([email protected]) Proofread by Donald Strachan ([email protected]) Cartography by Jillian Luff (www.mapgrafix.com) Typeset in Optima and Palatino by Rick Jones ([email protected]) Printed by nbmedia in Geneva, Switzerland ISBN 978-2-940548-09-5 2 Small Arms Survey HSBA Working Paper 35 Contents List of abbreviations and acronyms .................................................................................................................................... 4 I. Introduction and key findings .............................................................................................................................................. -

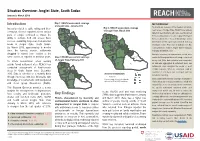

Jonglei State, South Sudan Introduction Key Findings

Situation Overview: Jonglei State, South Sudan January to March 2019 Introduction Map 1: REACH assessment coverage METHODOLOGY of Jonglei State, January 2019 To provide an overview of the situation in hard-to- Insecurity related to cattle raiding and inter- Map 3: REACH assessment coverage of Jonglei State, March 2019 reach areas of Jonglei State, REACH uses primary communal violence reported across various data from key informants who have recently arrived parts of Jonglei continued to impact the from, recently visited, or receive regular information ability to cultivate food and access basic Fangak Canal/Pigi from a settlement or “Area of Knowledge” (AoK). services, sustaining large-scale humanitarian Nyirol Information for this report was collected from key needs in Jonglei State, South Sudan. Ayod informants in Bor Protection of Civilians site, Bor By March 2019, approximately 5 months Town and Akobo Town in Jonglei State in January, since the harvest season, settlements February and March 2019. Akobo Duk Uror struggled to extend food rations to the In-depth interviews on humanitarian needs were Twic Pochalla same extent as reported in previous years. Map 2: REACH assessment coverage East conducted throughout the month using a structured of Jonglei State, February 2019 survey tool. After data collection was completed, To inform humanitarian actors working Bor South all data was aggregated at settlement level, and outside formal settlement sites, REACH has Pibor settlements were assigned the modal or most conducted assessments of hard-to-reach credible response. When no consensus could be areas in South Sudan since December found for a settlement, that settlement was not Assessed settlements 2015. -

SOUTH SUDAN Food Security Outlook Update May 2013 Crisis

SOUTH SUDAN Food Security Outlook Update May 2013 Crisis food insecurity peaks with the May-August lean season KEY MESSAGES Figure 1. Current food security outcomes, May to June 2013. • With the recent outbreak of conflict, food security outcomes are expected to be worst in Pibor County, Jonglei State, due to the impacts of prolonged, severe, and deteriorating civil security. Some food deficits (IPC Phase 3: Crisis) outcomes are expected at least through the Outlook period (September). • In Panyijiar and Mayendit counties in Unity state, as well as in Warrap and Lakes in the center of the country, intensive inter-ethnic conflict and some areas of excessive flooding in 2012 have contributed to IPC Phase 3 outcomes through August. • In the eastern flood plains of Upper Nile and northern Jonglei States (Nyirol, Uror and Ayod), poor 2012 production due to extreme flooding will lead to food deficits at the peak of the agricultural lean season through August. Source: FEWS NET Figure 2. Projected food security outcomes, July to • In the northern states, civil insecurity and restrictions to September 2013. trade and movement, though improving, are still likely to result in food deficits (IPC Phase 3: Crisis) through June/July. CURRENT SITUATION • Worsening civil security in Jonglei state has contributed to high and rising prices for sorghum (Figure 3) inconsistent with trends and levels in other parts of South Sudan. A number of schools, health centers, and Figure 3. Nominal sorghum prices in reference markets serving Pibor county. April 2013 % difference % difference Market price (SSP) vs. Mar 2013 vs. Apr 2012 Bor 5.71 Stable 35% Kapoeta 3.20 30% Unknown Source: WFP, FEWS NET Source: FEWS NET markets have closed since the end of April. -

Nyirol Final Report

South Sudan NUTRITIONAL ANTHROPOMETRIC SURVEY CHILDREN UNDER 5 YEARS OLD LANKIEN AND TUT PAYAMS, NYIROL COUNTY JONGLEI STATE 16TH AUGUST – 12TH SEPTEMBER 2007 Edward Kutondo- Survey Program Manager Imelda .V. Awino – Nutritionist Simon Tut Gony- Program Assisstant 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ACF-USA acknowledges the support, commitment and cooperation of the following institutions and persons, who enabled the team to successfully actualize survey objectives: ª Office of United States Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA) for funding the survey; ª The Sudan Relief and Rehabilitation Commission (SSSRRC) Nyirol County for availing relevant data and ensuring smooth flow of activities; ª The entire survey team for their hard work, team spirit, commitment and endurance despite the difficult terrain; ª South Sudan Ministry of Health in Jonglei State, MSF-OCA, Sudan Red Crescent, Cush Community Relief International for availing staff for capacity building; ª Parents, caretakers and the local authority for their cooperation. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS .I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................................................................4 .II. INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................................................10 .III. OBJECTIVES .............................................................................................................................................11 .IV. METHODOLOGY.......................................................................................................................................11 -

IOM SOUTH SUDAN EVENT TRACKING and RAPID NEEDS ASSESSMENT in PIBOR TOWN As of 24 May 2021

IOM SOUTH SUDAN EVENT TRACKING AND RAPID NEEDS ASSESSMENT IN PIBOR TOWN As of 24 May 2021 Assessment Recommendations: ● Humanitarian actors should immediately respond to the emergency humanitarian needs of over seven thousand internally displaced persons living in collective centres and spontaneous sites within Pibor town. While many people from areas not directly affected by violence have already returned, IDPs from the Nanaam area and Gumruk payam lost their homes and most of their belongings. They are likely to remain in Pibor until the situation stabilizes and assistance is provided for them to return. ● Humanitarian actors should assess needs and scale up the response in Gumruk Centre, which suffered its second attack in twelve months, and to other affected communities within the Greater Pibor Administrative Area (GPAA), such as those living in the border area of Kongor boma (Lekuangole payam) along the Nanaam river. Previous assessments have shown that hard-to-reach areas in GPAA face the highest levels of need across sectors and may soon become inaccessible with the onset of the rainy season and likely flooding. ● The Government of South Sudan and UNMISS peacekeepers should step up efforts to protect civilians across the GPAA and in Pibor Town and facilitate the work of humanitarian and development partners while peacebuilding actors continue to engage in, and expand, community dialogues to address the root causes of conflict in coordination with partners on the ground. Repeated failures to prevent and address conflict in Jonglei and the GPAA over the past decade-plus have resulted in the multiple displacements of a large numbers of civilians, collapse of livelihoods systems and destruction of local infrastructure, and catastrophic levels of humanitarian need. -

South Sudan: Bi-Weekly Humanitarian Situation Report Emergency Type: Humanitarian Crises Issue 21| Date: 15– 31 December 2020

South Sudan: Bi-Weekly Humanitarian Situation Report Emergency type: Humanitarian Crises Issue 21| Date: 15– 31 December 2020 KEY FIGURES COVID-19 FLOODS 3612 63 78156 3158 1,034,000 485, 000 4 7.5M 2.24M confirmed deaths Tests recoveries people Displaced Deaths People in Need of South Sudanese cases performed affected Humanitarian Refugees Assistance HIGHLIGHTS 1.67M 1.4M Internally Malnourished Children • A cumulative total of 3 612 COVID-19 confirmed cases and 63 deaths (case Displaced fatality rate of 1.7%) have been reported in the country as of 6 January 2021. • An immediate scale-up of multi-sectoral humanitarian assistance has been recommended to save lives and avert total collapse of livelihoods in the severely food insecure (IPC Phase 5) populations in Aweil South, Tonj North, 188K 483K Persons living in Malnourished Women Tonj East, Tonj South, Pibor and Akobo. PoC1 • To prevent flood affected communities from cholera, over 63 000 (88% coverage) individuals aged one year and above vaccinated against cholera in Bor South County of Jonglei state during the first round of the campaign that 73 5.82M ended on 20 December 2020. The second round of the campaign will begin Stabilization Severely Food Insecure on 10 January 2021. Centers • Out of 22 samples collected from suspected human cases in Yirol West and Yirol East, 12 samples have tested negative for Rift valley fever,Crimean- Congo hemorrhagic fever, Ebola virus, and Marburg. Results for the other samples are pending. 121 Children under one year vaccinated 066 with oral polio vaccine (20%) Initial numbers of children vaccinated 962 against measles 158 Counties with confirmed measles 10 outbreaks in 2020 PoC1 s sites with confirmed measles 1 outbreaks in 2020 Counties with malaria cases 00 surpassing their set thresholds WHO handed over the renovated buildings in Juba Teaching Hospital to the Deputy Director of the Hospital. -

The Murle Tribe: from Khartoum Applied College and a Radio/ TV Production Certificate from Omdurman Radio/ TV Training Institute

WL KNO EDGE NCE ISM SA ER IS E A TE N K N O K C E N N T N I S E S J E N A 3 V H A A The Foreign Military Studies Office (FMSO) at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, is an open source N H Z И O E P W O I T research organization of the U.S. Army. It was founded in 1986 as an innovative program that E D N E Z I A M I C O N brought together military specialists and civilian academics to focus on military and security O C C I O T N S H O E L C A I N M Z E N O T topics derived from unclassified, foreign media. Today FMSO maintains this research tradition of special insight and highly collaborative work by conducting unclassified research on foreign perspectives of defense and security issues that are understudied or unconsidered. Author Background Ahmed Osman was born in Shendi, Sudan. He graduated with an advanced diploma in journalism The Murle Tribe: from Khartoum Applied College and a radio/ TV production certificate from Omdurman Radio/ TV Training Institute. After moving to the United States in 1999 he obtained a BA in Fine Arts An Analysis of Its Conflicts and a Master’s degree in instructional technology from American Intercontinental University. In addition, he is an experienced radio producer, digital designer, instructional technologist and with the Nuer, Dinka and technical support specialist with native fluency in Arabic. Government of South Sudan AHMED OSMAN WL KNO EDGE NCE ISM SA ER IS E A TE N K N O K C E N N T N I S E S J E N A 3 V H A A N H Z И O E P W O I T E D N E Z I A M I C O N O C C I O T N S H O E L C A I N M Z E N O T Cover image: Silhouette of tribal markings belonging to a young girl from the Karo Tribe in Murle, Omo Valley, Ethiopia. -

Treatment and Prevention of Acute Malnutrition in Jonglei & Greater

Treatment and Prevention of Acute Malnutrition in Jonglei & Greater Pibor Administrative Area, Republic of South Sudan Date: Prepared by: January 31, 2018 Dr. Taban Martin Vitale I. Demographic Information 1. City & State: Bor, Jonglei State, and Greater Pibor Administrative Area, Republic of South Sudan 2. Organization: Real Medicine Foundation, South Sudan (www.realmedicinefoundation.org) United Nations Children’s Fund (www.unicef.org) 3. Project Title: Treatment and Prevention of Acute Malnutrition 4. Reporting Period: October 1, 2017 – December 31, 2017 5. Project Location (region & city/town/village): Ayod County of Jonglei State and Boma County of Greater Pibor Administrative Area 6. Target Population: Direct project beneficiaries for the year 2017 tabulated below: Table 1: SAM children directly targeted County SAM Children to Benefit SAM Children to Benefit Total from OTP from SC Ayod 2,944 440 3,384 Boma 1,469 0 1,469 Total 4,413 440 4,853 Table 2: MAM children and pregnant and lactating women (PLW) directly targeted County MAM Children to Benefit PLW to Benefit from TSFP from TSFP Ayod 4,329 3,375 Boma 1,898 1,467 Total 6,227 4,842 Direct project beneficiaries are approximately 140,517 people living in the payams assigned to RMF, and indirect beneficiaries include the whole population of the two counties, estimated to be 340,661 projected from the 2008 South Sudan Population and Housing Census. The nutrition service centers also receive beneficiaries from neighboring counties and internally displaced persons (IDPs) from various areas of Jonglei and neighboring states. II. Project Information 7. Project Goals: The overall goal of this project is to reduce the global acute malnutrition (GAM) rate to an acceptable level of less than 15% in each of the payams assigned to RMF. -

Jonglei State, South Sudan January - March 2020

Situation Overview: Jonglei State, South Sudan January - March 2020 Introduction METHODOLOGY Reported humanitarian needs increased across is likely a consequence of severe flooding Map 1: Assessment coverage in Jonglei State in To provide an indicative overview of the situation Jonglei State throughout the first quarter of which appears to have brought forward January (A), February (B) and March (C), 2020: in hard-to-reach areas of Jonglei State, REACH 2020. An early depletion of food stocks, limited the onset of the lean season from March uses primary data from key informants (KIs) who access to livestock and increasing market to January.3 Moving forward, heavy rains A B have recently arrived from, recently visited, or prices resulted in widespread food insecurity. in the coming months may further reduce receive regular information from a settlement or Moving forward, the existing humanitarian crisis humanitarian access to extremely vulnerable “Area of Knowledge” (AoK). Information for this report was collected from KIs in Bor Protection of could be exacerbated further by the direct and populations in hard-to-reach areas. Civilians (PoC) site, Bor Town and Akobo Town in indirect effects of COVID-19. • The proportion of assessed settlements January, February and March 2020. To inform humanitarian actors working outside reporting protection concerns remained Monthly interviews on humanitarian needs were formal settlement sites, REACH has conducted stable, with 79% reporting most people felt conducted using a structured survey tool. After data collection was completed, all data was assessments of hard-to-reach areas in South safe most of the time in March. However, the 0 - 4.9% aggregated at settlement level, and settlements Sudan since December 2015. -

Rapid Assessment Mission

GREATER PIBOR ADMINISTRATIVE AREA (GPAA), PIBOR COUNTY: THE BACK TO LEARNING PROGRAM RAPID ASSESSMENT MISSION (Dates: Thursday February 5th To Thursday February 12th 2015) Some of the demobilized child soldiers in Pibor County; the prime target of the Back to Learning Program Mission Report Compiled By: Johnson K. NDICHU, Programs Coordinator, Nile Hope. Tel. +211 920010325/ +211 977481400/ +211 927117916 Email: [email protected] / [email protected] 1 | P a g e Prologue ollowing the launch of the Back to Learning (BTL) Program and some maiden meetings with UNICEF, Education Sector, Nile Hope Team, spearheaded by the Programs Coordinator, launched a Rapid Assessment Mission in the Greater Pibor Administrative Area (GPAA), specifically Pibor and Gumuruk Counties from Thursday February 5th To Thursday February 12th 2015. The following individuals comprised the Mission Team: i) Johnson K. Ndichu (Programs Coordinator) ii) Ajang A. Awai (Jonglei State Coordinator) iii) Baba Sebit Baba (GPAA Field Coordinator) iv) Lazarus Kiir (Literacy and Peace-Building Project Manager); v) Ujum Ter (Education Program Assistant) The overarching objective of the Mission was to find out the general status of the various sectors (Education, WASH, Health, Nutrition, Protection, Food Security and Livelihoods) especially in Pibor County. Specifically, the Team sought to familiarize and find out the post-conflict status of education in Pibor County in terms of infrastructure, teacher availability and compensation, state of school supplies and furniture, state of School WASH, specific information from the demobilized soldiers as well as the structure of the GPAA Education Department and availability of education data. We also got to get a glimpse of who is doing what in GPAA and mainly Pibor County, that has seen multiple agencies (INGOs and NGOs) migrate to the area for myriad responses To a very large extent, the Mission can be rated as a success story. -

A/HRC/46/53 Advance Edited Version

A/HRC/46/53 Advance edited version Distr.: General 4 February 2021 Human Rights Council Forty-sixth session 22 February–19 March 2021 Agenda item 4 Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention Report of the Commission on Human Rights in South Sudan Summary In the present report, submitted pursuant to Human Rights Council resolution 43/27, the Commission on Human Rights in South Sudan provides an overview of the situation of human rights in South Sudan and updates the Council on critical developments and incidents on which the Commission has collected and preserved evidence.1 1 See also the conference room paper containing the evidence gathered by and main findings of the Commission (A/HRC/46/CRP.2), available on the webpage of the Commission (www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/CoHSouthSudan/Pages/Index.aspx). A/HRC/43/56 I. Introduction 1. In its resolution 31/20, the Human Rights Council established the Commission on Human Rights in South Sudan for a period of one year. The Commission submitted its first report to the Council at its thirty-fourth session (A/HRC/34/63). 2. In its resolution 34/25, the Human Rights Council extended the mandate of the Commission for another year, and requested it to continue to monitor and report on the situation of human rights in South Sudan, to make recommendations to prevent further deterioration of the situation, and to report and provide guidance on transitional justice, including reconciliation. 3. The Human Rights Council also requested the Commission to determine and report the facts and circumstances of, to collect and preserve evidence of, and to clarify responsibility for alleged gross violations and abuses of human rights and related crimes, including sexual and gender-based violence and ethnic violence, with a view to ending impunity and providing accountability.