Real but Fragile: the Greater Pibor Administrative Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Interaction Between International Aid and South Sudanese

Lost in Translation: The interaction between international humanitarian aid and South Sudanese accountability systems September 2020 This research was conducted by the Conflict Sensitivity Resource Facility (CSRF) in August and September 2019 and was funded by the UK, Swiss, Dutch and Canadian donor missions in South Sudan. The CSRF is implemented by a consortium of the NGOs Saferworld and swisspeace. It is intended to support conflict-sensitive aid programming in South Sudan. This research would not have been possible without the South Sudanese and international aid actors who generously gave their time and insights. It is dedicated to the South Sudanese aid workers who tirelessly balance their personal and professional cultures to deliver assistance to those who need it. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................ 1 Recommendations ............................................................................................................................................. 2 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Background ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 Methodology and limitations ........................................................................................................................... -

Republic of South Sudan "Establishment Order

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN "ESTABLISHMENT ORDER NUMBER 36/2015 FOR THE CREATION OF 28 STATES" IN THE DECENTRALIZED GOVERNANCE SYSTEM IN THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN Order 1 Preliminary Citation, commencement and interpretation 1. This order shall be cited as "the Establishment Order number 36/2015 AD" for the creation of new South Sudan states. 2. The Establishment Order shall come into force in thirty (30) working days from the date of signature by the President of the Republic. 3. Interpretation as per this Order: 3.1. "Establishment Order", means this Republican Order number 36/2015 AD under which the states of South Sudan are created. 3.2. "President" means the President of the Republic of South Sudan 3.3. "States" means the 28 states in the decentralized South Sudan as per the attached Map herewith which are established by this Order. 3.4. "Governor" means a governor of a state, for the time being, who shall be appointed by the President of the Republic until the permanent constitution is promulgated and elections are conducted. 3.5. "State constitution", means constitution of each state promulgated by an appointed state legislative assembly which shall conform to the Transitional Constitution of South Sudan 2011, amended 2015 until the permanent Constitution is promulgated under which the state constitutions shall conform to. 3.6. "State Legislative Assembly", means a legislative body, which for the time being, shall be appointed by the President and the same shall constitute itself into transitional state legislative assembly in the first sitting presided over by the most eldest person amongst the members and elect its speaker and deputy speaker among its members. -

The Black Christs of the Black Christs of by J. Penn De

The Black Christs of Africa A Bible of Poems By J. Penn de Ngong Above all, I am not concerned with Poetry. My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity. Wilfred Owen, British Poet Poem 22 petition for partition We, the auto-government of the Republic of Ruralia, Voicing the will of the democratic public of Ruralia, Are writing to your Theocratic Union of Urbania. Our grievances are on the following discontentment: Firstly, your purely autocratic Government of Urbania, Has solely dishonoured and condemned the document That we all signed – and codenamed – “Bible of Peace”. You’ve violated its gospel, the cause of our fatal disagreement; Wealth: You’re feeding our autonomous nation with ration apiece. In your annual tour, compare our city – Metropollutant – of Ruralia With its posh sister city of Urbania, proudly dubbed Metropolitania. All our resources, on our watching, are consumed up in Urbania. Our intellectuals and workforce are abundant but redundant. Henceforth, right here, we demarcate to be independent! You are busy strategizing to turn Ruralia into Somalia: Yourselves landlords, creating warlords, tribal militia, And bribing our politicians to speak out your voice, And turning our villages into large ghettos of slum, And our own towns into large cities of Islam. With these experiences, we’ve no choice, But t’ ask, demand, fight... for our voice. They oft’ say the end justifies the means, We, Ruralians, must reform all our ruins; The first option: thru the ballot, Last action: bullet! J. Penn de Ngong (John Ngong Alwong Alith as known in his family) came into this world on a day nobody knows. -

Strategic Peacebuilding- the Role of Civilians and Civil Society in Preventing Mass Atrocities in South Sudan

SPECIAL REPORT Strategic Peacebuilding The Role of Civilians and Civil Society in Preventing Mass Atrocities in South Sudan The Cases of the SPLM Leadership Crisis (2013), the Military Standoff at General Malong’s House (2017), and the Wau Crisis (2016–17) NYATHON H. MAI JULY 2020 WEEKLY REVIEW June 7, 2020 The Boiling Frustrations in South Sudan Abraham A. Awolich outh Sudan’s 2018 peace agreement that ended the deadly 6-year civil war is in jeopardy, both because the parties to it are back to brinkmanship over a number S of mildly contentious issues in the agreement and because the implementation process has skipped over fundamental st eps in a rush to form a unity government. It seems that the parties, the mediators and guarantors of the agreement wereof the mind that a quick formation of the Revitalized Government of National Unity (RTGoNU) would start to build trust between the leaders and to procure a public buy-in. Unfortunately, a unity government that is devoid of capacity and political will is unable to address the fundamentals of peace, namely, security, basic services, and justice and accountability. The result is that the citizens at all levels of society are disappointed in RTGoNU, with many taking the law, order, security, and survival into their own hands due to the ubiquitous absence of government in their everyday lives. The country is now at more risk of becoming undone at its seams than any other time since the liberation war ended in 2005. The current st ate of affairs in the country has been long in the making. -

South Sudan Village Assessment Survey

IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY SOUTH SUD AN IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX SOUTH SUDAN SOUTH SUDAN VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY DATA COLLECTION: August-November 2019 COUNTIES: Bor South, Rubkona, Wau THEMATIC AREAS: Shelter and Land Ownership, Access and Communications, Livelihoods, Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies, Health, WASH, Education, Protection 1 IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY SOUTH SUD AN CONTENTS RUBKONA COUNTY OVERVIEW 15 DISPLACEMENT DYNAMICS 15 RETURN PATTERNS 15 PAYAM CONTEXTUAL INFORMATION 16 KEY FINDINGS 17 Shelter and Land Ownership 17 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 Access and Communications 17 LIST OF ACRONYMS 3 Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies 17 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 Livelihoods 18 BACKROUND 6 Health 19 WASH 19 METHODOLOGY 6 Education 20 LIMITATIONS 7 Protection 20 WAU COUNTY OVERVIEW 8 BOR SOUTH COUNTY OVERVIEW 21 DISPLACEMENT DYNAMICS 8 RETURN PATTERNS 8 DISPLACEMENT DYNAMICS 21 PAYAM CONTEXTUAL INFORMATION 9 RETURN PATTERNS 21 KEY FINDINGS 10 PAYAM CONTEXTUAL INFORMATION 22 KEY FINDINGS 23 Shelter and Land Ownership 10 Access and Communications 10 Shelter and Land Ownership 23 Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies 10 Access and Communications 23 Livelihoods 11 Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies 23 Health 12 Livelihoods 24 WASH 13 Health 25 Protection 13 Education 26 Education 14 WASH 27 Protection 27 2 3 IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY SOUTH SUD AN LIST OF ACRONYMS AIDS: Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome -

Upper Nile State, South Sudan June 2017

Situation Overview: Upper Nile State, South Sudan June 2017 SUDAN Introduction previous REACH assessments of hard-to- presence returned to the averages from April reach areas of Upper Nile State. (22% June, 42% May, 28% April).1 This may Despite a potential respite in fighting in lower MANYO be indicative of the slowing of movement due This Situation Overview outlines displacement counties along the western bank, dispersed to the rainy season. Although fighting that took RENK and access to basic services in Upper Nile fighting and widespread displacements trends place in Panyikang and Fashoda appeared to in June 2017. The first section analyses continued into June and impeded the provision subside, clashes between armed groups armed displacement trends in Upper Nile State. of primary needs and access to basic services groups reportedly commenced in Manyo and The second section outlines the population for assessed settlements. Only 45% of assessed Renk Counties, causing the local population to MELUT dynamics in the assessed settlements, as well settlements reported adequate access to food flee across the border as well as to Renk Town.2 and half reported access to healthcare facilities as access to food and basic services for both FASHODA These clashes may have also contributed to across Upper Nile State, while the malnutrition, MABAN IDP and non-displaced communities. MALAKAL a lack of IDPs, with no assessed settlement malaria and cholera concerns reported in May PANYIKANG BALIET Baliet, Maban, Melut and Renk Counties had in Manyo reporting an IDP presence in June, continued into June. LONGOCHUK less than 5% settlement coverage (Map 1), compared to 50% in May. -

The Crisis in South Sudan

Conflict in South Sudan and the Challenges Ahead Lauren Ploch Blanchard Specialist in African Affairs September 22, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R43344 Conflict in South Sudan and the Challenges Ahead Summary South Sudan, which separated from Sudan in 2011 after almost 40 years of civil war, was drawn into a devastating new conflict in late 2013, when a political dispute that overlapped with preexisting ethnic and political fault lines turned violent. Civilians have been routinely targeted in the conflict, often along ethnic lines, and the warring parties have been accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity. The war and resulting humanitarian crisis have displaced more than 2.7 million people, including roughly 200,000 who are sheltering at U.N. peacekeeping bases in the country. Over 1 million South Sudanese have fled as refugees to neighboring countries. No reliable death count exists. U.N. agencies report that the humanitarian situation, already dire with over 40% of the population facing life-threatening hunger, is worsening, as continued conflict spurs a sharp increase in food prices. Famine may be on the horizon. Aid workers, among them hundreds of U.S. citizens, are increasingly under threat—South Sudan overtook Afghanistan as the country with the highest reported number of major attacks on humanitarians in 2015. At least 62 aid workers have been killed during the conflict, and U.N. experts warn that threats are increasing in scope and brutality. In August 2015, the international community welcomed a peace agreement signed by the warring parties, but it did not end the conflict. -

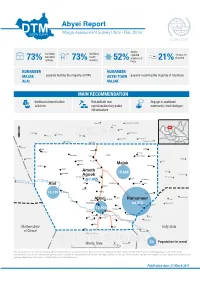

20170331 Abyei

Abyei Report Village Assessment Survey | Nov - Dec 2016 IOM OIM bomas functional functional reported villages are 73% education 73% health 52% presence of 21% deserted facilities facilities UXOs. RUMAMEER RUMAMEER MAJAK payams hosting the majority of IDPs ABYEI TOWN payams receiving the majority of returnees ALAL MAJAK MAIN SURVEY RECOMMENDATIONS MAIN RECOMMENDATION livelihood diversication Rehabilitate and Engage in sustained activities operationalize key public community-level dialogue infrastructure Ed Dibeikir Ramthil Raqabat Rumaylah Nyam Roba Nabek Umm Biura El Amma Mekeines Zerafat SUDABeida N Ed Dabkir Shagawah Duhul Kawak Al Agad Al Aza Meiram Tajiel Dabib Farouk Debab Pariang Um Khaer Langar Di@ra Raqaba Kokai Es Saart El Halluf Pagol Bioknom Pandal Ajaj Kajjam Majak Ghabush En Nimr Shigei Di@ra Ameth Nyak Kolading 15,685 Gumriak 2 Aguok Goli Ed Dahlob En Neggu Fagai 1,055 Dumboloya Nugar As Sumayh Alal Alal Um Khariet Bedheni Baar Todach Saheib Et Timsah Noong 13,130 Ed Derangis Tejalei Feid El Kok Dungoup Padit DokurAbyeia Rumameer Todyop Madingthon 68,372 Abu Qurun Thurpader Hamir Leu 12,900 Awoluum Agany Toak Banton Athony Marial Achak Galadu Arik Athony Grinঞ Agach Awal Aweragor Madul Northern Bahr Agok Unity State Lort Dal el Ghazal Abiemnom Baralil Marsh XX Population in need SOUTH SUDANMolbang Warrap State Ajakuao 0 25 50 km The boundaries on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the Government of the Republic of South Sudan or IOM. This map is for planning purposes only. IOM cannot guarantee this map is error free and therefore accepts no liability for consequential and indirect damages arising from its use. -

Secretary-General's Report on South Sudan (September 2020)

United Nations S/2020/890 Security Council Distr.: General 8 September 2020 Original: English Situation in South Sudan Report of the Secretary-General I. Introduction 1. The present report is submitted pursuant to Security Council resolution 2514 (2020), by which the Council extended the mandate of the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) until 15 March 2021 and requested me to report to the Council on the implementation of the Mission’s mandate every 90 days. It covers political and security developments between 1 June and 31 August 2020, the humanitarian and human rights situation and progress made in the implementation of the Mission’s mandate. II. Political and economic developments 2. On 17 June, the President of South Sudan, Salva Kiir, and the First Vice- President, Riek Machar, reached a decision on responsibility-sharing ratios for gubernatorial and State positions, ending a three-month impasse on the allocations of States. Central Equatoria, Eastern Equatoria, Lakes, Northern Bahr el-Ghazal, Warrap and Unity were allocated to the incumbent Transitional Government of National Unity; Upper Nile, Western Bahr el-Ghazal and Western Equatoria were allocated to the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army in Opposition (SPLM/A-IO); and Jonglei was allocated to the South Sudan Opposition Alliance. The Other Political Parties coalition was not allocated a State, as envisioned in the Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan, in which the coalition had been guaranteed 8 per cent of the positions. 3. On 29 June, the President appointed governors of 8 of the 10 States and chief administrators of the administrative areas of Abyei, Ruweng and Pibor. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/24/2021 04:59:59AM Via Free Access “They Are Now Community Police” 411

international journal on minority and group rights 22 (2015) 410-434 brill.com/ijgr “They Are Now Community Police”: Negotiating the Boundaries and Nature of the Government in South Sudan through the Identity of Militarised Cattle-keepers Naomi Pendle PhD Candidate, London School of Economics, London, UK [email protected] Abstract Armed, cattle-herding men in Africa are often assumed to be at a relational and spatial distance from the ‘legitimate’ armed forces of the government. The vision constructed of the South Sudanese government in 2005 by the Comprehensive Peace Agreement removed legitimacy from non-government armed groups including localised, armed, defence forces that protected communities and cattle. Yet, militarised cattle-herding men of South Sudan have had various relationships with the governing Sudan Peoples’ Liberation Movement/Army over the last thirty years, blurring the government – non government boundary. With tens of thousands killed since December 2013 in South Sudan, questions are being asked about options for justice especially for governing elites. A contextual understanding of the armed forces and their relationship to gov- ernment over time is needed to understand the genesis and apparent legitimacy of this violence. Keywords South Sudan – policing – vigilantism – transitional justice – war crimes – security © NAOMI PENDLE, 2015 | doi 10.1163/15718115-02203006 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 (CC-BY-NC 4.0) License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/Downloaded from Brill.com09/24/2021 04:59:59AM via free access “they Are Now Community Police” 411 1 Introduction1 On 15 December 2013, violence erupted in Juba, South Sudan among Nuer sol- diers of the Presidential Guard. -

South Sudan's

Untapped and Unprepared Dirty Deals Threaten South Sudan’s Mining Sector April 2020 Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Invitation to Exploitation 4 Beneath the Battlefield: Mineral Development During Conflict 12 Indications of Possible Money Laundering 19 Recommendations 20 We are grateful for the support we receive from our donors who have helped make our work possible. To learn more about The Sentry’s funders, please visit The Sentry website at www.thesentry.org/about/. UNTAPPED AND UNPREPARED: DIRTY DEALS THREATEN SOUTH SUDAN’S MINING SECTOR TheSentry.org Executive Summary South Sudan’s mining sector has seen rapid development in recent years, and preliminary reports suggest that the industry could become an engine for major economic growth. However, ineffective accountability mechanisms, an opaque corporate landscape, and inadequate due diligence have exposed the sector to abuse by bad actors within South Sudan’s ruling clique. The Sentry has found that existing laws have proven insufficient bulwarks against abuse, raising concerns that the country’s mineral wealth could do little more than spur the kind of violent competition that has ravaged the oil sector. Although South Sudan took welcome steps to reform the mining sector in 2012, some government officials, their relatives, and their close associates have fostered a weak regulatory environment susceptible to exploitation. In one example of how the privileged few have apparently exploited kleptocratic arrangements, President Salva Kiir’s daughter partly owns a company with three active licenses, while another company with three licenses lists former Vice President James Wani Igga’s son as a shareholder. Ashraf Seed Ahmed Hussein Ali, a businessman commonly known as Al-Cardinal who was placed under Global Magnitsky sanctions in October 2019, reportedly owns the company currently holding the greatest number of licenses.1 In the gold-rich region of Kapoeta, state government officials have begun issuing licenses independently of the central government. -

An Analysis of Pibor County, South Sudan from the Perspective of Displaced People

Researching livelihoods and services affected by conflict Livelihoods, access to services and perceptions of governance: An analysis of Pibor county, South Sudan from the perspective of displaced people Working Paper 23 Martina Santschi, Leben Moro, Philip Dau, Rachel Gordon and Daniel Maxwell September 2014 About us Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium (SLRC) aims to generate a stronger evidence base on how people make a living, educate their children, deal with illness and access other basic services in conflict-affected situations (CAS). Providing better access to basic services, social protection and support to livelihoods matters for the human welfare of people affected by conflict, the achievement of development targets such as the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and international efforts at peace- and state-building. At the centre of SLRC’s research are three core themes, developed over the course of an intensive one- year inception phase: . State legitimacy: experiences, perceptions and expectations of the state and local governance in conflict-affected situations . State capacity: building effective states that deliver services and social protection in conflict- affected situations . Livelihood trajectories and economic activity under conflict The Overseas Development Institute (ODI) is the lead organisation. SLRC partners include the Centre for Poverty Analysis (CEPA) in Sri Lanka, Feinstein International Center (FIC, Tufts University), the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU), the Sustainable Development Policy