A/HRC/46/53 Advance Edited Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Warrap State SOUTH SUDAN

COMMUNITY CONSULTATION REPORT Warrap State SOUTH SUDAN Bureau for Community Security South Sudan Peace and Small Arms Control and Reconciliation Commission United Nations Development Programme The Bureau for Community Security and Small Arms Control under the Ministry of Interior is the Gov- ernment agency of South Sudan mandated to address the threats posed by the proliferation of small arms and community insecurity to peace and development. The South Sudan Peace and Reconciliation Commission is mandated to promote peaceful co-existence amongst the people of South Sudan and advise the Government on matters related to peace. The United Nations Development Programme in South Sudan, through the Community Security and Arms Control Project supports the Bureau strengthen its capacity in the area of community security and arms control at the national, state, and county levels. Cover photo: © UNDP/Sun-Ra Lambert Baj COMMUNITY CONSULTATION REPORT Warrap State South Sudan Published by South Sudan Bureau for Community Security and Small Arms Control South Sudan Peace and Reconciliation Commission United Nations Development Programme MAY 2012 JUBA, SOUTH SUDAN CONTENTS Acronyms ........................................................................................................................... i Foreword ........................................................................................................................... .ii Executive Summary ......................................................................................................... -

Wetlands of the Nile Basin the Many Eco for Their Liveli This Chapt Distribution, Functions and Contribution to Contribution Livelihoods They Provide

important role particular imp into wetlands budget (Sutch 11 in the Blue N icantly 1110difi Wetlands of the Nile Basin the many eco for their liveli This chapt Distribution, functions and contribution to contribution livelihoods they provide. activities, ane rainfall (i.e. 1 Lisa-Maria Rebelo and Matthew P McCartney climate chan: food securit; currently eX' arc under tb Key messages water resour support • Wetlands occur extensively across the Nile Basin and support the livelihoods ofmillions of related ;;ervi people. Despite their importance, there are big gaps in the knowledge about the current better evalu: status of these ecosystems, and how populations in the Nile use them. A better understand systematic I ing is needed on the ecosystem services provided by the difl:erent types of wetlands in the provide. Nile, and how these contribute to local livelihoods. • While many ofthe Nile's wetlands arc inextricably linked to agricultural production systems the basis for making decisions on the extent to which, and how, wetlands can be sustainably used for agriculture is weak. The Nile I: • Due to these infi)fl11atio!1 gaps, the future contribution of wetlands to agriculture is poorly the basin ( understood, and wetlands are otten overlooked in the Nile Basin discourse on water and both the E agriculture. While there is great potential for the further development of agriculture and marsh, fen, fisheries, in particular in the wetlands of Sudan and Ethiopia, at the same time many that is stat wetlands in the basin are threatened by poor management practices and populations. which at \, In order to ensure that the future use of wetlands for agriculture will result in net benefits (i.e. -

An Article on Explosion of Ethnic Violence in Warrap State in South Sudan

South American Journal of Academic Research Special Edition May 2016 An article on explosion of ethnic violence in Warrap state In south Sudan Article by Emmanuel Moju, MSC on clinical psychology, Texila American University, South Sudan Email: [email protected] Abstract As matter of facts, ethnic conflict is an outcome of number of interrelated factors. It is important to cautiously and thoroughly study each of these factors and establish relationship among the characteristics involved. Appropriate approach is useful in an endeavor to resolve ethnic conflicts through a peaceful means. Ethnic conflict leads, among other things, to the breakdown of law and order, the disruption of economic activities, political stability, humanitarian crises and a state of uncertainty which prevent long run investment and development efforts and peace. A case on line is the conflict that broke out between the SPLA and SPLA in opposition on 15th December 2013, in South Sudan, all the developments made from independence till the date were gone. Violent ethnic conflict leads to extraordinary displacement of people including vulnerable groups such as women, children, the elderly as well as the disabled who often are seriously affected by violent conflict. Therefore, it is worthwhile to give due concern to interethnic relations and manage it cautiously and systematically. Conflict is like contagious disease. Unwise handling of conflict gives it the opportunity to widespread all of a sudden. If it occurred, conflict must be handled at its early stages. Once allowed to escalate, it would change to violence that cannot be easily remedied and control. A good example is the Central Africa Republic ongoing ethnic violence between the Muslims and the Christians (Alemayehu, Fantaw. -

Promoting Peace and Resilience in Unity State, South Sudan

BRIEF / FEBRUARY 2021 Promoting peace and resilience in Unity state, South Sudan The town of Bentiu, located in Rubkona County, is the comprising 11,529 households.1 Although people capital of the oil-rich Unity state and is predominately living in the PoC site are provided with protection and inhabited by the Nuer people. A series of waterways and humanitarian assistance, they still face challenges swamps cover large parts of the state and these provide including economic hardship, being targeted by armed pasture in the dry season for animals belonging to Nuer groups, violent crime, revenge killings inside the PoC and Dinka pastoralists, as well as other pastoralist site, and outbreaks of disease as a result of the crowded groups from neighbouring Sudan who migrate with conditions in which they live. In July 2020, UNMISS their animals into South Sudan during dry seasons in initiated consultations about its intention to re-designate search of grazing land and water. Unity state also sits the PoC sites in the country to IDP camps and hand over on some of the largest oil deposits in South Sudan and a responsibility of these camps to the government of South considerable amount of petroleum-related activity takes Sudan. People living in the Bentiu PoC site expressed place in and around Bentiu. The production of oil has concern at this plan – while conditions inside the contributed to fuelling conflicts in the state, resulting in camp are very poor, IDPs fear the threat of violence and displacement and environmental degradation. insecurity outside the PoCs if responsibility is transferred. -

Strategic Peacebuilding- the Role of Civilians and Civil Society in Preventing Mass Atrocities in South Sudan

SPECIAL REPORT Strategic Peacebuilding The Role of Civilians and Civil Society in Preventing Mass Atrocities in South Sudan The Cases of the SPLM Leadership Crisis (2013), the Military Standoff at General Malong’s House (2017), and the Wau Crisis (2016–17) NYATHON H. MAI JULY 2020 WEEKLY REVIEW June 7, 2020 The Boiling Frustrations in South Sudan Abraham A. Awolich outh Sudan’s 2018 peace agreement that ended the deadly 6-year civil war is in jeopardy, both because the parties to it are back to brinkmanship over a number S of mildly contentious issues in the agreement and because the implementation process has skipped over fundamental st eps in a rush to form a unity government. It seems that the parties, the mediators and guarantors of the agreement wereof the mind that a quick formation of the Revitalized Government of National Unity (RTGoNU) would start to build trust between the leaders and to procure a public buy-in. Unfortunately, a unity government that is devoid of capacity and political will is unable to address the fundamentals of peace, namely, security, basic services, and justice and accountability. The result is that the citizens at all levels of society are disappointed in RTGoNU, with many taking the law, order, security, and survival into their own hands due to the ubiquitous absence of government in their everyday lives. The country is now at more risk of becoming undone at its seams than any other time since the liberation war ended in 2005. The current st ate of affairs in the country has been long in the making. -

The Crisis in South Sudan

Conflict in South Sudan and the Challenges Ahead Lauren Ploch Blanchard Specialist in African Affairs September 22, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R43344 Conflict in South Sudan and the Challenges Ahead Summary South Sudan, which separated from Sudan in 2011 after almost 40 years of civil war, was drawn into a devastating new conflict in late 2013, when a political dispute that overlapped with preexisting ethnic and political fault lines turned violent. Civilians have been routinely targeted in the conflict, often along ethnic lines, and the warring parties have been accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity. The war and resulting humanitarian crisis have displaced more than 2.7 million people, including roughly 200,000 who are sheltering at U.N. peacekeeping bases in the country. Over 1 million South Sudanese have fled as refugees to neighboring countries. No reliable death count exists. U.N. agencies report that the humanitarian situation, already dire with over 40% of the population facing life-threatening hunger, is worsening, as continued conflict spurs a sharp increase in food prices. Famine may be on the horizon. Aid workers, among them hundreds of U.S. citizens, are increasingly under threat—South Sudan overtook Afghanistan as the country with the highest reported number of major attacks on humanitarians in 2015. At least 62 aid workers have been killed during the conflict, and U.N. experts warn that threats are increasing in scope and brutality. In August 2015, the international community welcomed a peace agreement signed by the warring parties, but it did not end the conflict. -

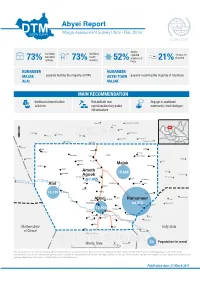

20170331 Abyei

Abyei Report Village Assessment Survey | Nov - Dec 2016 IOM OIM bomas functional functional reported villages are 73% education 73% health 52% presence of 21% deserted facilities facilities UXOs. RUMAMEER RUMAMEER MAJAK payams hosting the majority of IDPs ABYEI TOWN payams receiving the majority of returnees ALAL MAJAK MAIN SURVEY RECOMMENDATIONS MAIN RECOMMENDATION livelihood diversication Rehabilitate and Engage in sustained activities operationalize key public community-level dialogue infrastructure Ed Dibeikir Ramthil Raqabat Rumaylah Nyam Roba Nabek Umm Biura El Amma Mekeines Zerafat SUDABeida N Ed Dabkir Shagawah Duhul Kawak Al Agad Al Aza Meiram Tajiel Dabib Farouk Debab Pariang Um Khaer Langar Di@ra Raqaba Kokai Es Saart El Halluf Pagol Bioknom Pandal Ajaj Kajjam Majak Ghabush En Nimr Shigei Di@ra Ameth Nyak Kolading 15,685 Gumriak 2 Aguok Goli Ed Dahlob En Neggu Fagai 1,055 Dumboloya Nugar As Sumayh Alal Alal Um Khariet Bedheni Baar Todach Saheib Et Timsah Noong 13,130 Ed Derangis Tejalei Feid El Kok Dungoup Padit DokurAbyeia Rumameer Todyop Madingthon 68,372 Abu Qurun Thurpader Hamir Leu 12,900 Awoluum Agany Toak Banton Athony Marial Achak Galadu Arik Athony Grinঞ Agach Awal Aweragor Madul Northern Bahr Agok Unity State Lort Dal el Ghazal Abiemnom Baralil Marsh XX Population in need SOUTH SUDANMolbang Warrap State Ajakuao 0 25 50 km The boundaries on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the Government of the Republic of South Sudan or IOM. This map is for planning purposes only. IOM cannot guarantee this map is error free and therefore accepts no liability for consequential and indirect damages arising from its use. -

Local History of Ethiopia Ma - Mezzo © Bernhard Lindahl (2008)

Local History of Ethiopia Ma - Mezzo © Bernhard Lindahl (2008) ma, maa (O) why? HES37 Ma 1258'/3813' 2093 m, near Deresge 12/38 [Gz] HES37 Ma Abo (church) 1259'/3812' 2549 m 12/38 [Gz] JEH61 Maabai (plain) 12/40 [WO] HEM61 Maaga (Maago), see Mahago HEU35 Maago 2354 m 12/39 [LM WO] HEU71 Maajeraro (Ma'ajeraro) 1320'/3931' 2345 m, 13/39 [Gz] south of Mekele -- Maale language, an Omotic language spoken in the Bako-Gazer district -- Maale people, living at some distance to the north-west of the Konso HCC.. Maale (area), east of Jinka 05/36 [x] ?? Maana, east of Ankar in the north-west 12/37? [n] JEJ40 Maandita (area) 12/41 [WO] HFF31 Maaquddi, see Meakudi maar (T) honey HFC45 Maar (Amba Maar) 1401'/3706' 1151 m 14/37 [Gz] HEU62 Maara 1314'/3935' 1940 m 13/39 [Gu Gz] JEJ42 Maaru (area) 12/41 [WO] maass..: masara (O) castle, temple JEJ52 Maassarra (area) 12/41 [WO] Ma.., see also Me.. -- Mabaan (Burun), name of a small ethnic group, numbering 3,026 at one census, but about 23 only according to the 1994 census maber (Gurage) monthly Christian gathering where there is an orthodox church HET52 Maber 1312'/3838' 1996 m 13/38 [WO Gz] mabera: mabara (O) religious organization of a group of men or women JEC50 Mabera (area), cf Mebera 11/41 [WO] mabil: mebil (mäbil) (A) food, eatables -- Mabil, Mavil, name of a Mecha Oromo tribe HDR42 Mabil, see Koli, cf Mebel JEP96 Mabra 1330'/4116' 126 m, 13/41 [WO Gz] near the border of Eritrea, cf Mebera HEU91 Macalle, see Mekele JDK54 Macanis, see Makanissa HDM12 Macaniso, see Makaniso HES69 Macanna, see Makanna, and also Mekane Birhan HFF64 Macargot, see Makargot JER02 Macarra, see Makarra HES50 Macatat, see Makatat HDH78 Maccanissa, see Makanisa HDE04 Macchi, se Meki HFF02 Macden, see May Mekden (with sub-post office) macha (O) 1. -

Secretary-General's Report on South Sudan (September 2020)

United Nations S/2020/890 Security Council Distr.: General 8 September 2020 Original: English Situation in South Sudan Report of the Secretary-General I. Introduction 1. The present report is submitted pursuant to Security Council resolution 2514 (2020), by which the Council extended the mandate of the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) until 15 March 2021 and requested me to report to the Council on the implementation of the Mission’s mandate every 90 days. It covers political and security developments between 1 June and 31 August 2020, the humanitarian and human rights situation and progress made in the implementation of the Mission’s mandate. II. Political and economic developments 2. On 17 June, the President of South Sudan, Salva Kiir, and the First Vice- President, Riek Machar, reached a decision on responsibility-sharing ratios for gubernatorial and State positions, ending a three-month impasse on the allocations of States. Central Equatoria, Eastern Equatoria, Lakes, Northern Bahr el-Ghazal, Warrap and Unity were allocated to the incumbent Transitional Government of National Unity; Upper Nile, Western Bahr el-Ghazal and Western Equatoria were allocated to the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army in Opposition (SPLM/A-IO); and Jonglei was allocated to the South Sudan Opposition Alliance. The Other Political Parties coalition was not allocated a State, as envisioned in the Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan, in which the coalition had been guaranteed 8 per cent of the positions. 3. On 29 June, the President appointed governors of 8 of the 10 States and chief administrators of the administrative areas of Abyei, Ruweng and Pibor. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/24/2021 04:59:59AM Via Free Access “They Are Now Community Police” 411

international journal on minority and group rights 22 (2015) 410-434 brill.com/ijgr “They Are Now Community Police”: Negotiating the Boundaries and Nature of the Government in South Sudan through the Identity of Militarised Cattle-keepers Naomi Pendle PhD Candidate, London School of Economics, London, UK [email protected] Abstract Armed, cattle-herding men in Africa are often assumed to be at a relational and spatial distance from the ‘legitimate’ armed forces of the government. The vision constructed of the South Sudanese government in 2005 by the Comprehensive Peace Agreement removed legitimacy from non-government armed groups including localised, armed, defence forces that protected communities and cattle. Yet, militarised cattle-herding men of South Sudan have had various relationships with the governing Sudan Peoples’ Liberation Movement/Army over the last thirty years, blurring the government – non government boundary. With tens of thousands killed since December 2013 in South Sudan, questions are being asked about options for justice especially for governing elites. A contextual understanding of the armed forces and their relationship to gov- ernment over time is needed to understand the genesis and apparent legitimacy of this violence. Keywords South Sudan – policing – vigilantism – transitional justice – war crimes – security © NAOMI PENDLE, 2015 | doi 10.1163/15718115-02203006 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 (CC-BY-NC 4.0) License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/Downloaded from Brill.com09/24/2021 04:59:59AM via free access “they Are Now Community Police” 411 1 Introduction1 On 15 December 2013, violence erupted in Juba, South Sudan among Nuer sol- diers of the Presidential Guard. -

Annex a Eastern Nile Water Simulation Model

Annex A Eastern Nile Water Simulation Model Hydrological boundary conditions 1206020-000-VEB-0017, 4 December 2012, draft Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Hydraulic infrastructure 3 2.1 River basins and hydraulic infrastructure 3 2.2 The Equatorial Lakes basin 3 2.3 White Nile from Mongalla to Sobat mouth 5 2.4 Baro-Akobo-Sobat0White Nile Sub-basin 5 2.4.1 Abay-Blue Nile Sub-basin 6 2.4.2 Tekeze-Setit-Atbara Sub-basin 7 2.4.3 Main Nile Sub-basin 7 2.5 Hydrological characteristics 8 2.5.1 Rainfall and evaporation 8 2.5.2 River flows 10 2.5.3 Key hydrological stations 17 3 Database for ENWSM 19 3.1 General 19 3.2 Data availability 19 3.3 Basin areas 20 4 Rainfall and effective rainfall 23 4.1 Data sources 23 4.2 Extension of rainfall series 23 4.3 Effective rainfall 24 4.4 Overview of average monthly and annual rainfall and effective rainfall 25 5 Evaporation 31 5.1 Reference evapotranspiration 31 5.1.1 Penman-Montheith equation 32 5.1.2 Aerodynamic resistance ra 32 5.1.3 ‘Bulk’ surface resistance rs 33 5.1.4 Coefficient of vapour term 34 5.1.5 Net energy term 34 5.2 ET0 in the basins 35 5.2.1 Baro-Akobo-Sobat-White Nile 35 5.2.2 Abay-Blue Nile 36 5.2.3 Tekeze-Setit-Atbara 37 5.3 Open water evaporation 39 5.4 Open water evaporation relative to the refrence evapotranspiration 40 5.5 Overview of applied evapo(transpi)ration values 42 6 River flows 47 6.1 General 47 6.2 Baro-Akobo-Sobat-White Nile sub-basin 47 6.2.1 Baro at Gambela 47 Annex A Eastern Nile Water Simulation Model i 1206020-000-VEB-0017, 4 December 2012, draft 6.2.2 Baro upstream -

South Sudan's

Untapped and Unprepared Dirty Deals Threaten South Sudan’s Mining Sector April 2020 Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Invitation to Exploitation 4 Beneath the Battlefield: Mineral Development During Conflict 12 Indications of Possible Money Laundering 19 Recommendations 20 We are grateful for the support we receive from our donors who have helped make our work possible. To learn more about The Sentry’s funders, please visit The Sentry website at www.thesentry.org/about/. UNTAPPED AND UNPREPARED: DIRTY DEALS THREATEN SOUTH SUDAN’S MINING SECTOR TheSentry.org Executive Summary South Sudan’s mining sector has seen rapid development in recent years, and preliminary reports suggest that the industry could become an engine for major economic growth. However, ineffective accountability mechanisms, an opaque corporate landscape, and inadequate due diligence have exposed the sector to abuse by bad actors within South Sudan’s ruling clique. The Sentry has found that existing laws have proven insufficient bulwarks against abuse, raising concerns that the country’s mineral wealth could do little more than spur the kind of violent competition that has ravaged the oil sector. Although South Sudan took welcome steps to reform the mining sector in 2012, some government officials, their relatives, and their close associates have fostered a weak regulatory environment susceptible to exploitation. In one example of how the privileged few have apparently exploited kleptocratic arrangements, President Salva Kiir’s daughter partly owns a company with three active licenses, while another company with three licenses lists former Vice President James Wani Igga’s son as a shareholder. Ashraf Seed Ahmed Hussein Ali, a businessman commonly known as Al-Cardinal who was placed under Global Magnitsky sanctions in October 2019, reportedly owns the company currently holding the greatest number of licenses.1 In the gold-rich region of Kapoeta, state government officials have begun issuing licenses independently of the central government.