2021 SEG CODES Student Chapter Field Trip Report King Island, Tasmania, Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download PDF About Minerals Sorted by Mineral Name

MINERALS SORTED BY NAME Here is an alphabetical list of minerals discussed on this site. More information on and photographs of these minerals in Kentucky is available in the book “Rocks and Minerals of Kentucky” (Anderson, 1994). APATITE Crystal system: hexagonal. Fracture: conchoidal. Color: red, brown, white. Hardness: 5.0. Luster: opaque or semitransparent. Specific gravity: 3.1. Apatite, also called cellophane, occurs in peridotites in eastern and western Kentucky. A microcrystalline variety of collophane found in northern Woodford County is dark reddish brown, porous, and occurs in phosphatic beds, lenses, and nodules in the Tanglewood Member of the Lexington Limestone. Some fossils in the Tanglewood Member are coated with phosphate. Beds are generally very thin, but occasionally several feet thick. The Woodford County phosphate beds were mined during the early 1900s near Wallace, Ky. BARITE Crystal system: orthorhombic. Cleavage: often in groups of platy or tabular crystals. Color: usually white, but may be light shades of blue, brown, yellow, or red. Hardness: 3.0 to 3.5. Streak: white. Luster: vitreous to pearly. Specific gravity: 4.5. Tenacity: brittle. Uses: in heavy muds in oil-well drilling, to increase brilliance in the glass-making industry, as filler for paper, cosmetics, textiles, linoleum, rubber goods, paints. Barite generally occurs in a white massive variety (often appearing earthy when weathered), although some clear to bluish, bladed barite crystals have been observed in several vein deposits in central Kentucky, and commonly occurs as a solid solution series with celestite where barium and strontium can substitute for each other. Various nodular zones have been observed in Silurian–Devonian rocks in east-central Kentucky. -

Geology of the Berne Quadrangle Black Hills South Dakota

Geology of the Berne Quadrangle Black Hills South Dakota GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 297-F Prepared partly on behalf of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission Geology of the Berne Quadrangle Black Hills South Dakota By JACK A. REDDEN PEGMATITES AND OTHER PRECAMBRIAN ROCKS IN THE SOUTHERN BLACK HILLS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 297-F Prepared partly on behalf of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1968 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William T. Pecora, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402 CONTENTS Page Page Abstract._ _-------------_-___________-_____________ 343 Pegmatites Continued Introduction.______________________________________ 344 Mineralogy __ _____________-___-___-_-------_--- 378 Previous work__________________________________ 345 Origin.- --___-____-_-_-_---------------------_ 380 Fieldwork and acknowledgments._-_-_--__________ 345 Paleozoic and younger rocks. ________________________ 381 Geologic setting____--__-______________________ ____ 345 Deadwood Formation, __________________________ 381 Metamorphic rocks_________________________________ 347 Englewood Formation.. _ __________--____-_-__--_ 381 Stratigraphic units west of Grand Junction fault___- 347 Pahasapa Limestone- _______-_____.__-----_-- - 381 Vanderlehr Formation.._____________________ 347 Quaternary and Recent deposits. _________________ 382 Biotite-plagioclase gneiss.________________ -

The Diversity of Magmatism at a Convergent Plate

1 Flow of partially molten crust controlling construction, growth and collapse of the Variscan orogenic belt: 2 the geologic record of the French Massif Central 3 4 Vanderhaeghe Olivier1, Laurent Oscar1,2, Gardien Véronique3, Moyen Jean-François4, Gébelin Aude5, Chelle- 5 Michou Cyril2, Couzinié Simon4,6, Villaros Arnaud7,8, Bellanger Mathieu9. 6 1. GET, UPS, CNRS, IRD, 14 avenue E. Belin, F-31400 Toulouse, France 7 2. ETH Zürich, Institute for Geochemistry and Petrology, Clausiusstrasse 25, CH-8038 Zürich, Switzerland 8 3. Université Lyon 1, ENS de Lyon, CNRS, UMR 5276 LGL-TPE, F-69622, Villeurbanne, France 9 4. Université de Lyon, Laboratoire Magmas et Volcans, UJM-UCA-CNRS-IRD, 23 rue Dr. Paul Michelon, 10 42023 Saint Etienne 11 5. School of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences, Plymouth University, Plymouth,UK 12 6. CRPG, Université de Lorraine, CNRS, UMR7358, 15 rue Notre Dame des Pauvres, F-54501 13 Vandoeuvre-lès-Nancy, France 14 7. Univ d’Orléans, ISTO, UMR 7327, 45071, Orléans, France ; CNRS, ISTO, UMR 7327, 45071 Orléans, 15 France ; BRGM, ISTO, UMR 7327, BP 36009, 45060 Orléans, France 16 8. University of Stellenbosch, Department of Earth Sciences, 7602 Matieland, South Africa 17 9. TLS Geothermics, 91 chemin de Gabardie 31200 Toulouse. 18 19 [email protected] 20 +33(0)5 61 33 47 34 21 22 Key words: 23 Variscan belt; French Massif Central; Flow of partially molten crust; Orogenic magmatism; Orogenic plateau; 24 Gravitational collapse. 25 26 Abstract 27 We present here a tectonic-geodynamic model for the generation and flow of partially molten rocks and for 28 magmatism during the Variscan orogenic evolution from the Silurian to the late Carboniferous based on a synthesis 29 of geological data from the French Massif Central. -

THE PARAGENETIC RELATIONSHIP of EPIDOTE-QUARTZ HYDROTHERMAL ALTERATION WITHIN the NORANDA VOLCANIC COMPLEX, QUEBEC R' the PARAGENETIC RELATIONSHIPS of EPIDOTE-QUARTZ

TH 1848 THE PARAGENETIC RELATIONSHIP OF EPIDOTE-QUARTZ HYDROTHERMAL ALTERATION WITHIN THE NORANDA VOLCANIC COMPLEX, QUEBEC r' THE PARAGENETIC RELATIONSHIPS OF EPIDOTE-QUARTZ HYDROTHERMAL ALTERATION WITHIN THE NORANDA VOLCANIC COMPLEX, QUEBEC Frank Santaguida (B.Sc., M.Sc.) Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Earth Sciences Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario, Canada May, 1999 Copyright © 1999, Frank Santaguida i The undersigned hereby recommend to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research acceptance of the thesis, THE PARAGENETIC RELATIONSHIPS OF EPIDOTE-QUARTZ HYDROTHERMAL ALTERATION WITHIN THE NORANDA VOLCANIC COMPLEX, QUEBEC submitted by Frank Santaguida (B.Sc., M.Sc.) in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ,n. cGJI, Chairman, Department of Earth Sciences \ NW Thesis Supervisor /4, ad,/ External Examiner ii ABSTRACT Epidote-quartz alteration is conspicuous throughout the central Noranda Volcanic Complex, but its relationship to the Volcanic-Hosted Massive Sulphide (VHMS) deposits is relatively unknown. A continuum of alteration textures exist that reflect epidote abundance as well as alteration intensity. The strongest epidote-quartz alteration phase is represented by small discrete "patches" of complete groundmass replacement that are concentrated in discrete zones. The largest and most intense zones are spatially contained in mafic volcanic eruptive centres, the Old Waite Paleofissure and the McDougall- Despina Eruptive Centre. Therefore, epidote-quartz alteration is regionally semi- conformable and is not restricted to the hangingwall or footwall of the VHMS deposits. Epidote-quartz alteration is absent from the alteration pipes associated with sulphide mineralization. -

Facies and Mafic

Metamorphic Facies and Metamorphosed Mafic Rocks l V.M. Goldschmidt (1911, 1912a), contact Metamorphic Facies and metamorphosed pelitic, calcareous, and Metamorphosed Mafic Rocks psammitic hornfelses in the Oslo region l Relatively simple mineral assemblages Reading: Winter Chapter 25. (< 6 major minerals) in the inner zones of the aureoles around granitoid intrusives l Equilibrium mineral assemblage related to Xbulk Metamorphic Facies Metamorphic Facies l Pentii Eskola (1914, 1915) Orijärvi, S. l Certain mineral pairs (e.g. anorthite + hypersthene) Finland were consistently present in rocks of appropriate l Rocks with K-feldspar + cordierite at Oslo composition, whereas the compositionally contained the compositionally equivalent pair equivalent pair (diopside + andalusite) was not biotite + muscovite at Orijärvi l If two alternative assemblages are X-equivalent, l Eskola: difference must reflect differing we must be able to relate them by a reaction physical conditions l In this case the reaction is simple: l Finnish rocks (more hydrous and lower MgSiO3 + CaAl2Si2O8 = CaMgSi2O6 + Al2SiO5 volume assemblage) equilibrated at lower En An Di Als temperatures and higher pressures than the Norwegian ones Metamorphic Facies Metamorphic Facies Oslo: Ksp + Cord l Eskola (1915) developed the concept of Orijärvi: Bi + Mu metamorphic facies: Reaction: “In any rock or metamorphic formation which has 2 KMg3AlSi 3O10(OH)2 + 6 KAl2AlSi 3O10(OH)2 + 15 SiO2 arrived at a chemical equilibrium through Bt Ms Qtz metamorphism at constant temperature and = -

Part 629 – Glossary of Landform and Geologic Terms

Title 430 – National Soil Survey Handbook Part 629 – Glossary of Landform and Geologic Terms Subpart A – General Information 629.0 Definition and Purpose This glossary provides the NCSS soil survey program, soil scientists, and natural resource specialists with landform, geologic, and related terms and their definitions to— (1) Improve soil landscape description with a standard, single source landform and geologic glossary. (2) Enhance geomorphic content and clarity of soil map unit descriptions by use of accurate, defined terms. (3) Establish consistent geomorphic term usage in soil science and the National Cooperative Soil Survey (NCSS). (4) Provide standard geomorphic definitions for databases and soil survey technical publications. (5) Train soil scientists and related professionals in soils as landscape and geomorphic entities. 629.1 Responsibilities This glossary serves as the official NCSS reference for landform, geologic, and related terms. The staff of the National Soil Survey Center, located in Lincoln, NE, is responsible for maintaining and updating this glossary. Soil Science Division staff and NCSS participants are encouraged to propose additions and changes to the glossary for use in pedon descriptions, soil map unit descriptions, and soil survey publications. The Glossary of Geology (GG, 2005) serves as a major source for many glossary terms. The American Geologic Institute (AGI) granted the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (formerly the Soil Conservation Service) permission (in letters dated September 11, 1985, and September 22, 1993) to use existing definitions. Sources of, and modifications to, original definitions are explained immediately below. 629.2 Definitions A. Reference Codes Sources from which definitions were taken, whole or in part, are identified by a code (e.g., GG) following each definition. -

Metamorphic Rocks.Pdf

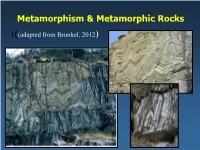

Metamorphism & Metamorphic Rocks (((adapted from Brunkel, 2012) Metamorphic Rocks . Changed rocks- with heat and pressure . But not melted . Change in the solid state . Textural changes (always) . Mineralogy changes (usually) Metamorphism . The mineral changes that transform a parent rock to into a new metamorphic rock by exposure to heat, stress, and fluids unlike those in which the parent rock formed. granite gneiss Geothermal gradient Types of Metamorphism . Contact metamorphism – – Happens in wall rock next to intrusions – HEAT is main metamorphic agent . Contact metamorphism Contact Metamorphism . Local- Usually a zone only a few meters wide . Heat from plutons intruded into “cooler” country rock . Usually forms nonfoliated rocks Types of Metamorphism . Hydrothermal metamorphism – – Happens along fracture conduits – HOT FLUIDS are main metamorphic agent Types of Metamorphism . Regional metamorphism – – Happens during mountain building – Most significant type – STRESS associated with plate convergence & – HEAT associated with burial (geothermal gradient) are main metamorphic agents . Contact metamorphism . Hydrothermal metamorphism . Regional metamorphism . Wide range of pressure and temperature conditions across a large area regional hot springs hydrothermal contact . Regional metamorphism Other types of Metamorphism . Burial . Fault zones . Impact metamorphism Tektites Metamorphism and Plate Tectonics . Fault zone metamorphism . Mélange- chaotic mixture of materials that have been crumpled together Stress (pressure) . From burial -

Tectono-Metamorphic Evolution and Timing of The

TECTONO-METAMORPHIC EVOLUTION AND TIMING OF THE MELTING PROCESSES IN THE SVECOFENNIAN TONALITE-TRONDHJEMITE MIGMATITE BELT: AN EXAMPLE FROM LUOPIOINEN, TAMPERE AREA, SOUTHERN FINLAND H. MOURI, K. KORSMÄN and H. HUHMA MOURI, H., KORSMAN, K. and HUHMA. H. 1999. Tectono-metamorphic evolution and timing of the melting processes in the Svecofennian Tonalite- Trondhjemite Migmatite Belt: An example from Luopioinen, Tampere area, southern Finland. Bulletin of the Geological Society of Finland 71, Part 1, 31- 56. The Svecofennian Orogen is in southern Finland characterized by two major migmatite belts. These are the so-called Granite Migmatite Belt, in which Kfs- rich leucosomes predominate, and the Tonalite-Trondhjemite Migmatite Belt, which is characterized by Kfs-poor leucosomes and borders the former belt in the north. The present paper deals with selected migmatitic rocks from the lat- ter belt. It is aimed to study the temporal and structural relationships of the dif- ferent leucosome generations, and to establish the pressure-temperature-time paths of this belt. The Tonalite-Trondhjemite Migmatite Belt consists mainly of migmatitic rocks with various types of synorogenic granitoids and minor mafic and ultramafic rocks. The mesosome of the migmatites consist of garnet-sillimanite-biotite-pla- gioclase-cordierite-quartz assemblages with rare K-feldspar and late andalusite. The oldest leucosomes are dominated by plagioclase and quartz, and the con- tent of K-feldspar increases in later leucosomes. Microtextural analysis in con- junction with THERMOCALC calculations and geothermometry shows that these rocks were metamorphosed at peak conditions of 700-750°C at 4-5 kbar and aH,0 = 0.4-0.7. -

Finding of Prehnite-Pumpellyite Facies Metabasites from the Kurosegawa Belt in Yatsushiro Area, Kyushu, Japan

Journal ofPrehnite Mineralogical-pumpellyite and Petrological facies metabasites Sciences, in Yatsushiro Volume 107, area, page Kyushu 99─ 104, 2012 99 LETTER Finding of prehnite-pumpellyite facies metabasites from the Kurosegawa belt in Yatsushiro area, Kyushu, Japan * * ** Kenichiro KAMIMURA , Takao HIRAJIMA and Yoshiyuki FUJIMOTO *Department of Geology and Mineralogy, Graduate School of Science, Kyoto University, Kitashirakawa Oiwakecho, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan ** Nittetsu-Kogyo Co., Ltd, 2-3-2 Marunouchi, Chiyoda, Tokyo 100-8377, Japan. Common occurrence of prehnite and pumpellyite is newly identified from metabasites of Tobiishi sub-unit in the Kurosegawa belt, Yatsushiro area, Kyushu, where Ueta (1961) had mapped as a greenschist facies area. Prehnite and pumpellyite are closely associated with chlorite, calcite and quartz, and they mainly occur in white colored veins or in amygdules in metabasites of the relevant area, but actinolite and epidote are rare in them. Pumpellyite is characterized by iron-rich composition (7.2-20.0 wt% as total iron as FeO) and its range almost overlaps with those in prehnite-pumpellyite facies metabasites of Ishizuka (1991). These facts suggest that the metabasites of the Tobiishi sub-unit suffered the prehnite-pumpellyite facies metamorphism, instead of the greenschist facies. Keywords: Prehnite-pumpellyite facies, Lawsonite-blueschist facies, Kurosegawa belt INTRODUCTION 1961; Kato et al., 1984; Maruyama et al., 1984; Tsujimori and Itaya, 1999; Tomiyoshi and Takasu, 2009). Until now, The subduction zone has an essential role for the global there is neither clear geological nor petrological evidence circulation of solid, fluid and volatile materials between suggesting what type of metamorphic rocks occupied the the surface and inside of the Earth at present. -

The Origin of Formation of the Amphibolite- Granulite Transition

The Origin of Formation of the Amphibolite- Granulite Transition Facies by Gregory o. Carpenter Advisor: Dr. M. Barton May 28, 1987 Table of Contents Page ABSTRACT . 1 QUESTION OF THE TRANSITION FACIES ORIGIN • . 2 DEFINING THE FACIES INVOLVED • • • • • • • • • • 3 Amphibolite Facies • • • • • • • • • • 3 Granulite Facies • • • • • • • • • • • 5 Amphibolite-Granulite Transition Facies 6 CONDITIONS OF FORMATION FOR THE FACIES INVOLVED • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 8 Amphibolite Facies • • • • • • • • 9 Granulite Facies • • • • • • • • • •• 11 Amphibolite-Granulite Transition Facies •• 13 ACTIVITIES OF C02 AND H20 . • • • • • • 1 7 HYPOTHESES OF FORMATION • • • • • • • • •• 19 Deep Crust Model • • • • • • • • • 20 Orogeny Model • • • • • • • • • • • • • 20 The Earth • • • • • • • • • • • • 20 Plate Tectonics ••••••••••• 21 Orogenic Events ••••••••• 22 Continent-Continent Collision •••• 22 Continent-Ocean Collision • • • • 24 CONCLUSION • . • 24 BIBLIOGRAPHY • • . • • • • 26 List of Illustrations Figure 1. Precambrian shields, platform sediments and Phanerozoic fold mountain belts 2. Metamorphic facies placement 3. Temperature and pressure conditions for metamorphic facies 4. Temperature and pressure conditions for metamorphic facies 5. Transformation processes with depth 6. Temperature versus depth of a descending continental plate 7. Cross-section of the earth 8. Cross-section of the earth 9. Collision zones 10. Convection currents Table 1. Metamorphic facies ABSTRACT The origin of formation of the amphibolite granulite transition -

Roadside Geology of Taiwan: a Field Guide

Roadside geology of taiwan: DȱHOGJXLGH 4UFQIBOJF$IFO About the cover 5IFDPWFSQIPUPEFQJDUTUIFGPMEFE HOFJTTFTJO5BSPLP/BUJPOBM1BSL "MMQIPUPTJOUIJTCPPLCZ 4UFQIBOJF$IFO 'PSNZGBNJMZ PREFACE 5IJTCPPLIBTCFFOXSJUUFOBTQBSUPGUIF 6OJWFSTJUZPG5PSPOUP`T#JH*EFBT&YQMPSJOH (MPCBM5BJXBODPNQFUJUJPO*UIBEBMXBZT CFFONZESFBNUPKVTUDBNQPVUBUBMPDBUJPO GPSBNPOUITBOELOPXFWFSZSPDLBOEPVU DSPQMJLFUIFCBDLPGNZIBOE BOEFWFOUVBMMZ XSJUFBpFMEHVJEFMJLFUIFPOFTUIBUHVJEFE NFUISPVHINZPXOHFPMPHZFEVDBUJPO *EJEO`UHFUUPTUBZGPSNPOUIT*OGBDU *XBTPOMZBCMFUPTUBZGPSPOFNPOUI CVUJU XBTTUJMMBOJODSFEJCMFFYQFSJFODF BOEUSVMZ IVNCMJOH 5BJXBO`THFPMPHZJTWFSZEJWFSTFBOE DPOUBJOTTPNBOZMPDBMTDBMFWBSJBUJPOTXIJDI BUNBOZUJNFTBSFIBSEBOEDIBMMFOHJOHUP pOE*U`TIPUBOEIVNJE NPTRVJUPFTBCPVOE BOEWFOPNPVTTOBLFTMVSLCFOFBUIUIFCSVTI #VUGPSUIPTFXIPBSFXJMMJOHUPUBLFUIFDIBM MFOHFBOEFYQFSJFODFXIBUUIJTMJUUMFJTMBOE DPVOUSZIBTUPP⒎FS ZPVXJMMOPUCFEJTBQ QPJOUFE 4UFQIBOJF C9. Tai Shan Tunnel 42 Table of contents C10. He Huan Shan 45 Southeast Coast 49 SE1. Fanshuliao Bridge 49 SE2. Baxian Cave 50 SE3. East Taiwan Ophiolite 52 Introduction i SE4. Wanrong 55 SE5. Taimali 56 Northern Coast 1 SE6. Lichi Badlands 57 N1. Yu-Ao Roadcut 1 SE7. Sanxiantai 61 N2. Yu-Ao Fishing Port 2 Southwest Coast 67 N3. Yehliu Geopark 4 N4. 13-Level Cu Refinery/Golden Waterfall 9 SW1. Wu Shan Ding 68 N5. Nanya Rock 11 SW2. Xing Yang Nu Hu Bee Farm 70 N6. Heping Dao (Peace Island) 14 SW3. Moon World 71 N7. Elephant’s Trunk/Shen Ao Promontory 16 SW4. Laterites in Southern Taiwan 74 N8. Longdong 20 N9. Bitou Cape 21 N10. Turtle Island 22 N11. Miaoli -

AM56 447.Pdf

THE AMERTCAN MINERAIOGIST, VOL. 56, MARCTI-APRIL, 1971 REFINEMENT OF THE CRYSTAL STRUCTURES OF EPIDOTE, ALLANITE AND HANCOCKITE W. A. Dorr,a.sr.,Department of Geology Universi.tyof California,Los Angeles90024. Assrnlcr Complete, three-dimensional crystal structure studies, including site-occupancy refine- ment, of a high-iron epidote, allanite, and hancockite have yielded cation distributions Car.ooCaroo(Alo gaFeo.os)Alr.oo(Alo zFeo.zo)SiaOrsH for epidote, Car oo(REo.zrCao:e)(AIs6t Feo ar)AL.oo(Alo.rzFeo$)SLOr3H for allanite, and Car.oo(PbosSro zrCao.zs) (Alo.eoFeo u)Alr.oo- (Al0 16Fe0.84)SLO13Hfor hancockite. These results when combined with those obtained in previous epidote-group refinements establish group-wide distribution trends in both the octahedral sites and the large-cation sites. Polyhedral expansion or contraction occurs at those sites involved in composition change but a simple mechanism, involving mainly rigid rotation of polyhedra, allows all other polyhedra to retain their same geometries in aII the structures examined. fNrnolucrtoN As part of a study of the structure and crystal chemistry of the epidote- group minerals, the first half of this paper reports the results of refine- ment of the crystal structures of three members of this group: allanite, hancockite, and (high-iron) epidote. Also, as an aid in assigning the ps2+, ps3+ occupancy of the sites in allanite, a preliminary Md,ssbauer spectral analysis of this mineral is presented. In the second half these structures are compared with three other members of the epidote group that were recently refined, clinozoisite (Dollase, 1968), piemontite (Dollase, 1969), and low-iron epidote (P.