R[-Re FUEFTE-.¡E-!-]S Eirat¡E C¡F Sr"¡¡Uv !-Mesrees! a Euumarv

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lobsters-Identification, World Distribution, and U.S. Trade

Lobsters-Identification, World Distribution, and U.S. Trade AUSTIN B. WILLIAMS Introduction tons to pounds to conform with US. tinents and islands, shoal platforms, and fishery statistics). This total includes certain seamounts (Fig. 1 and 2). More Lobsters are valued throughout the clawed lobsters, spiny and flat lobsters, over, the world distribution of these world as prime seafood items wherever and squat lobsters or langostinos (Tables animals can also be divided rougWy into they are caught, sold, or consumed. 1 and 2). temperate, subtropical, and tropical Basically, three kinds are marketed for Fisheries for these animals are de temperature zones. From such partition food, the clawed lobsters (superfamily cidedly concentrated in certain areas of ing, the following facts regarding lob Nephropoidea), the squat lobsters the world because of species distribu ster fisheries emerge. (family Galatheidae), and the spiny or tion, and this can be recognized by Clawed lobster fisheries (superfamily nonclawed lobsters (superfamily noting regional and species catches. The Nephropoidea) are concentrated in the Palinuroidea) . Food and Agriculture Organization of temperate North Atlantic region, al The US. market in clawed lobsters is the United Nations (FAO) has divided though there is minor fishing for them dominated by whole living American the world into 27 major fishing areas for in cooler waters at the edge of the con lobsters, Homarus americanus, caught the purpose of reporting fishery statis tinental platform in the Gul f of Mexico, off the northeastern United States and tics. Nineteen of these are marine fish Caribbean Sea (Roe, 1966), western southeastern Canada, but certain ing areas, but lobster distribution is South Atlantic along the coast of Brazil, smaller species of clawed lobsters from restricted to only 14 of them, i.e. -

The World Lobster Market

GLOBEFISH RESEARCH PROGRAMME The world lobster market Volume 123 GRP123coverB5.indd 1 23/01/2017 15:06:37 FAO GLOBEFISH RESEARCH PROGRAMME VOL. 123 The world lobster market by Graciela Pereira Helga Josupeit FAO Consultants Products, Trade and Marketing Branch Fisheries and Aquaculture Policy and Resources Division Rome, Italy FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2017 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. ISBN 978-92-5-109631-4 © FAO, 2017 FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. -

Tristan Da Cunha Fisheries Detailed Report 2017

Tristan da Cunha The Tristan da Cunha Archipelago is a group of volcanic islands in the South Atlantic (37o-41 o S; 9o-13o W), which includes the main island of Tristan da Cunha (96 km2), Gough Island (65 km2), Inaccessible Island (14 km2), Nightingale Island (3 km2) and two small islands close to Nightingale. The island group is situated around 1200 nautical miles south of St Helena and 1500 miles WSW of Cape Town, South Africa (Figure TdC-1). The island is part of the British Overseas Territory of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha, with the Governor based on St Helena. The Administrator is the Governor’s representative on Tristan da Cunha. Figure TdC-1. The South Atlantic Ocean showing the location of the Tristan da Cunha island group. The three northern islands (Tristan, Nightingale and Inaccessible) lie north of the Subtropical Convergence STC), a circumpolar oceanic front located at approximately 42˚S where the sea surface temperature (SST) drops sharply. Gough Island lies in the path of the STC, which moves north of the island during winter months. Average SST at Tristan da Cunha in the austral summer range from 15- 19˚C, and in winter it declines to 13-15˚C. At Gough Island SST is on average 3˚C cooler than at the Tristan group during all months. The tidal range is small, but trade winds and frequent storms means that the marine environment is high energy with frequent physical disturbance. The Tristan da Cunha 200 nautical mile Exclusive Fishing Zone (EFZ; Figure TdC-2) was established in 1983 and covers an area of 754,000 km2. -

Tesis De Yuniel Méndez Martínez

Programa de Estudios de Posgrado REQUERIMIENTOS DE PROTEÍNA Y ENERGÍA EN JUVENILES DE LANGOSTINO DE RÍO Macrobrachium americanum (Bate, 1868) TESIS Que para obtener el grado de Doctor en Ciencias Uso, Manejo y Preservación de los Recursos Naturales (Orientación en Acuicultura) P r e s e n t a Yuniel Méndez Martínez La Paz, Baja California Sur, marzo 2017. Comité Tutorial Dr. Edilmar Cortés Jacinto Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste S.C Director de Tesis Dra. María Concepción Lora Vilchis Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste S.C Co-tutor Dra. Guadalupe Fabiola Arcos Ortega Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste S.C Co-tutor Dr. Luis Rafael Martínez Córdova Universidad de Sonora Co-tutor Dr. Marcelo Ulises García Guerrero Centro Interdisciplinario de Investigación para el Desarrollo Integral Regional, Unidad Oaxaca-IPN Co-tutor Comité Revisor de Tesis Dr. Edilmar Cortés Jacinto Dra. María Concepción Lora Vilchis Dra. Guadalupe Fabiola Arcos Ortega Dr. Luis Rafael Martínez Córdova Dr. Marcelo Ulises García Guerrero Jurado de Examen Dr. Edilmar Cortés Jacinto Dra. María Concepción Lora Vilchis Dra. Guadalupe Fabiola Arcos Ortega Dr. Luis Rafael Martínez Córdova Dr. Marcelo Ulises García Guerrero Suplentes Dr. Stig Yamasaki Granados Dr. Ángel Isidro Campa Córdova ACTA DE LIBERACIÓN DE TESIS En la Ciudad de La Paz, B. C. S., siendo las 10:00 horas del día 10 del Mes de febrero del 2017, se procedió por los abajo firmantes, miembros de la Comisión Revisora de Tesis avalada por la Dirección de Estudios de Posgrado y Formación de Recursos Humanos del Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste, S. -

Fish, Crustaceans, Molluscs, Etc Capture Production by Species Items Indian Ocean, Western C-51 Poissons, Crustacés, Mollusques

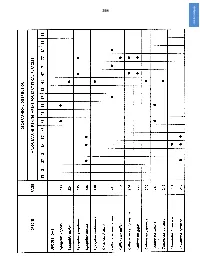

507 Fish, crustaceans, molluscs, etc Capture production by species items Indian Ocean, Western C-51 Poissons, crustacés, mollusques, etc Captures par catégories d'espèces Océan Indien, ouest (a) Peces, crustáceos, moluscos, etc Capturas por categorías de especies Océano Índico, occidental English name Scientific name Species group Nom anglais Nom scientifique Groupe d'espèces 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 Nombre inglés Nombre científico Grupo de especies t t t t t t t Hilsa shad Tenualosa ilisha 24 20 783 13 561 10 324 6 901 6 916 7 516 23 215 Bloch's gizzard shad Nematalosa nasus 24 250 271 350 414 340 325 325 Milkfish Chanos chanos 25 198 183 126 173 133 109 119 Leopard flounder Bothus pantherinus 31 80 77 76 75 87 75 83 Lefteye flounders nei Bothidae 31 25 18 31 30 30 30 30 Tonguefishes Cynoglossidae 31 1 025 1 042 1 057 1 075 1 090 1 123 1 256 Indian halibut Psettodes erumei 31 6 270 6 543 6 787 6 810 6 003 6 709 5 960 Flatfishes nei Pleuronectiformes 31 13 383 28 726 30 608 46 670 44 218 36 770 36 470 Common mora Mora moro 32 - - - 21 114 110 51 Unicorn cod Bregmaceros mcclellandi 32 267 547 922 1 765 95 66 28 Cape hakes Merluccius capensis, M.paradoxus 32 4 14 21 17 12 13 5 Bombay-duck Harpadon nehereus 33 134 034 119 923 175 166 183 062 105 039 103 046 135 231 Greater lizardfish Saurida tumbil 33 3 393 2 976 4 353 6 398 4 496 5 475 5 314 Brushtooth lizardfish Saurida undosquamis 33 33 15 24 9 9 12 10 Lizardfishes nei Synodontidae 33 16 213 10 734 20 792 23 981 42 714 57 247 68 811 Giant catfish Arius thalassinus 33 1 185 1 -

Climatic Change Drives Dynamic Source–Sink Relationships in Marine Species with High Dispersal Potential

Received: 22 September 2020 | Revised: 17 December 2020 | Accepted: 23 December 2020 DOI: 10.1002/ece3.7204 ORIGINAL RESEARCH Climatic change drives dynamic source–sink relationships in marine species with high dispersal potential Catarina N. S. Silva1 | Emma F. Young2 | Nicholas P. Murphy3 | James J. Bell4 | Bridget S. Green5 | Simon A. Morley2 | Guy Duhamel6 | Andrew C. Cockcroft7 | Jan M. Strugnell1,3 1Centre for Sustainable Tropical Fisheries and Aquaculture, James Cook University, Abstract Townsville, Qld, Australia While there is now strong evidence that many factors can shape dispersal, the mech- 2 British Antarctic Survey, Cambridge, UK anisms influencing connectivity patterns are species-specific and remain largely 3Department of Ecology, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Vic., Australia unknown for many species with a high dispersal potential. The rock lobsters Jasus 4School of Biological Sciences, Victoria tristani and Jasus paulensis have a long pelagic larval duration (up to 20 months) and University of Wellington, Wellington, New inhabit seamounts and islands in the southern Atlantic and Indian Oceans, respec- Zealand tively. We used a multidisciplinary approach to assess the genetic relationships be- 5Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies, University of Tasmania, Hobart, TAS, tween J. tristani and J. paulensis, investigate historic and contemporary gene flow, Australia and inform fisheries management. Using 17,256 neutral single nucleotide polymor- 6Département Adaptations du Vivant, BOREA, MNHN, Paris, France phisms we found low but significant genetic differentiation. We show that patterns 7Department of Agriculture, Forestry and of connectivity changed over time in accordance with climatic fluctuations. Historic Fisheries, South African Government, Cape migration estimates showed stronger connectivity from the Indian to the Atlantic Town, South Africa Ocean (influenced by the Agulhas Leakage). -

Climate Change Impacts on the Distribution of Coastal Lobsters

Marine Biology (2018) 165:186 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-018-3441-9 SHORT NOTE Climate change impacts on the distribution of coastal lobsters Joana Boavida‑Portugal1,2 · Rui Rosa2 · Ricardo Calado3 · Maria Pinto4 · Inês Boavida‑Portugal5 · Miguel B. Araújo1,6,7 · François Guilhaumon8,9 Received: 17 January 2018 / Accepted: 26 October 2018 / Published online: 16 November 2018 © Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2018 Abstract Coastal lobsters support important fsheries all over the world, but there is evidence that climate-induced changes may jeopardize some stocks. Here we present the frst global forecasts of changes in coastal lobster species distribution under climate change, using an ensemble of ecological niche models (ENMs). Global changes in richness were projected for 125 coastal lobster species for the end of the century, using a stabilization scenario (4.5 RCP). We compared projected changes in diversity with lobster fsheries data and found that losses in suitable habitat for coastal lobster species were mainly projected in areas with high commercial fshing interest, with species projected to contract their climatic envelope between 40 and 100%. Higher losses of spiny lobsters are projected in the coasts of wider Caribbean/Brazil, eastern Africa and Indo-Pacifc region, areas with several directed fsheries and aquacultures, while clawed lobsters are projected to shifts their envelope to northern latitudes likely afecting the North European, North American and Canadian fsheries. Fisheries represent an important resource for local and global economies and understanding how they might be afected by climate change scenarios is paramount when developing specifc or regional management strategies. -

Lobsters, Spiny-Rock Lobsters Capture Production by Species, Fishing Areas

361 Lobsters, spiny-rock lobsters Capture production by species, fishing areas and countries or areas B-43 Homards, langoustes Captures par espèces, zones de pêche et pays ou zones Bogavantes, langostas Capturas por especies, áreas de pesca y países o áreas Species, Fishing area Espèce, Zone de pêche 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 Especie, Área de pesca t t t t t t t t t t Longlegged spiny lobster Langouste diablotin Langosta duende Panulirus longipes 2,29(01)001,01 LOJ 61 China,Taiwan 7 8 13 10 11 31 17 20 15 14 Japan 1 300 1 401 1 335 1 193 1 120 1 215 1 186 1 297 1 199 1 100 Korea Rep 734 554 1 111 1 093 1 151 1 303 704 589 615 508 61 Fishing area total 2 041 1 963 2 459 2 296 2 282 2 549 1 907 1 906 1 829 1 622 Species total 2 041 1 963 2 459 2 296 2 282 2 549 1 907 1 906 1 829 1 622 Ornate spiny lobster Langouste ornée Langosta ornamentada Panulirus ornatus 2,29(01)001,06 NUR 51 Tanzania ... ... ... 495 476 471 497 493 565 557 51 Fishing area total ... ... ... 495 476 471 497 493 565 557 Species total ... ... ... 495 476 471 497 493 565 557 Caribbean spiny lobster Langouste blanche Langosta común del Caribe Panulirus argus 2,29(01)001,08 SLC 31 Anguilla 220 F 232 131 115 128 144 140 134 207 F 290 Antigua Barb 318 165 103 175 229 156 106 170 165 F 165 F Bahamas 6 977 6 896 7 138 9 692 8 505 9 761 6 088 6 569 6 526 8 482 Belize 630 642 624 672 833 660 652 650 855 774 Bermuda 31 31 38 39 45 47 31 38 35 30 Bonaire/Eust .. -

5. Index of Scientific and Vernacular Names

click for previous page 277 5. INDEX OF SCIENTIFIC AND VERNACULAR NAMES A Abricanto 60 antarcticus, Parribacus 209 Acanthacaris 26 antarcticus, Scyllarus 209 Acanthacaris caeca 26 antipodarum, Arctides 175 Acanthacaris opipara 28 aoteanus, Scyllarus 216 Acanthacaris tenuimana 28 Arabian whip lobster 164 acanthura, Nephropsis 35 ARAEOSTERNIDAE 166 acuelata, Nephropsis 36 Araeosternus 168 acuelatus, Nephropsis 36 Araeosternus wieneckii 170 Acutigebia 232 Arafura lobster 67 adriaticus, Palaemon 119 arafurensis, Metanephrops 67 adriaticus, Palinurus 119 arafurensis, Nephrops 67 aequinoctialis, Scyllarides 183 Aragosta 120 Aesop slipper lobster 189 Aragosta bianca 122 aesopius, Scyllarus 216 Aragosta mauritanica 122 affinis, Callianassa 242 Aragosta mediterranea 120 African lobster 75 Arctides 173 African spear lobster 112 Arctides antipodarum 175 africana, Gebia 233 Arctides guineensis 176 africana, Upogebia 233 Arctides regalis 177 Afrikanische Languste 100 ARCTIDINAE 173 Agassiz’s lobsterette 38 Arctus 216 agassizii, Nephropsis 37 Arctus americanus 216 Agusta 120 arctus, Arctus 218 Akamaru 212 Arctus arctus 218 Akaza 74 arctus, Astacus 218 Akaza-ebi 74 Arctus bicuspidatus 216 Aligusta 120 arctus, Cancer 217 Allpap 210 Arctus crenatus 216 alticrenatus, Ibacus 200 Arctus crenulatus 218 alticrenatus septemdentatus, Ibacus 200 Arctus delfini 216 amabilis, Scyllarus 216 Arctus depressus 216 American blunthorn lobster 125 Arctus gibberosus 217 American lobster 58 Arctus immaturus 224 americanus, Arctus 216 arctus lutea, Scyllarus 218 americanus, -

Fisheries Centre Research Reports 2015 Volume 23 Number 1

ISSN 1198-6727 MARINE FISHERIES CATCHES OF SUBANTARCTIC ISLANDS, 1950 TO 2010 Fisheries Centre Research Reports 2015 Volume 23 Number 1 ISSN 1198-6727 Fisheries Centre Research Reports 2015 Volume 23 Number 1 Marine Fisheries Catches of SubAntarctic Islands, 1950 to 2010 Fisheries Centre, University of British Columbia, Canada Marine Fisheries Catches of SubAntarctic Islands, 1950 to 2010 edited by Maria Lourdes D. Palomares and Daniel Pauly Fisheries Centre Research Reports 23(1) 48 pages © published 2015 by The Fisheries Centre, University of British Columbia 2202 Main Mall Vancouver, B.C., Canada, V6T 1Z4 ISSN 1198-6727 Marine Fisheries Catches of SubAntarctic Islands, 1950-2010, Palomares, MLD and Pauly D (eds.) Marine Fisheries Catches of SubAntarctic Islands, 1950 to 2010. M.L.D. Palomares and D. Pauly (editors) Fisheries Centre Research Reports 23(1) Fisheries Centre, University of British Columbia Table of Contents Page Preface ii Fisheries of the Falkland Islands and the South M.L.D. Palomares and D. Pauly 1 Georgia, South Sandwich and South Orkney Islands The fish and fisheries of Bouvet Island A. Padilla, K. Zylich, D. Zeller and D. 21 Pauly A short history of the fisheries of Crozet Islands P. Pruvost, G. Duhamel, N. Gasco, 31 and M.L.D. Palomares La pêche aux îles Saint Paul et Amsterdam (with P. Pruvost, G. Duhamel, 37 an extended English abstract) F. Le Manach, and M.L.D. Palomares i Marine Fisheries Catches of SubAntarctic Islands, 1950 to 2010, Palomares, M.L.D., Pauly, D. (eds.) Preface This report presents catch 'reconstructions' for six groups of islands that are part of, or near the sub- Antarctic convergence: France's Crozet and St Paul & Amsterdam, Norway’s Bouvet Island and the United Kingdom's Falkland, South Georgia and South Sandwich, and Orkney Islands. -

Crustacean Biology Journal of Crustacean Biology Journal of Crustacean Biology (2017) 1–7

Journal of Crustacean Biology Journal of Crustacean Biology Journal of Crustacean Biology (2017) 1–7. doi:10.1093/jcbiol/rux051 Density and gender segregation effects in the culture of the caridean ornamental red cherry shrimp Neocaridina davidi Bouvier, 1904 (Caridea: Atyidae) Nicolás D. Vazquez1,2, Karine Delevati-Colpo3, Daniela E. Sganga1,2 and Laura S. López-Greco1,2 1Laboratorio de Biología de la Reproducción y el Crecimiento de Crustáceos, Departamento de Biodiversidad y Biología Experimental, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Ciudad Universitaria C1428EGA, Buenos Aires, Argentina; 2Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas-Instituto de Biodiversidad y Biología Experimental y Aplicada, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Ciudad Universitaria C1428EGA, Buenos Aires, Argentina; and 3Instituto de Limnología Dr. Raúl A. Ringuelet, Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, La Plata, 1900, Buenos Aires, Argentina Correspondence: L.S. López-Greco: e-mail: [email protected] (Received 15 March 2017; accepted 4 May 2017) ABSTRACT The effect of density on growth, sex ratio, survival, and biochemical composition of the red cherry shrimp, Neocaridina davidi Bouvier, 1904, was studied to determine optimum rear- ing conditions in this ornamental species. It was tested whether gender segregation affected growth and survival of the species. To test the effect of density (Experiment 1), hatched –1 juvenile shrimp were kept at three different densities: 2.5, 5, and 10 individuals l (D2.5, D5 and D10, respectively). To test the effect of gender segregation (Experiment 2), 30-day juve- niles were reared in three conditions: culture with only females, culture with only males, and mixed culture (females: males 1:1) at 5 individuals l–1 density. -

Click for Next Page Click for Previous Page 265

264 click for next page click for previous page 265 4. BIBLIOGRAPHY Albert, F., 1898. La langosta de Juan Fernandez i la posibilidad de su propagación en la costa Chilena. Revista Chilena Historia natural, 2:5-11, 17-23,29-31, 1 tab Alcock, A., 1901. A descriptive catalogue of the Indian deep-Sea Crustacea Decapoda Macrura and Anomala in the Indian Museum. Being a revised account of the deep-sea species collected by the Royal Indian Marine Survey Ship Investigator: 1-286, i-iv, pls 1-3 Alcock, A. & A.R.S. Anderson, 1896. Illustrations of the Zoology of the Royal Indian Marine Surveying Steamer Investigator, under the command of Commander CF. Oldham, R.N. Crustacea (4):pls 1-6-27 Alcock, A. & A.F. McArdle, 1902. Illustrations of the Zoology of the Royal Indian Marine Survey Ship Investigator, under the command of Captain T.H. Heming, R.N. Crustacea, (10), pls 56-67 Allsopp, W.H.L., 1968. Report to the government of British Honduras (Belize) on investigations into marine fishery management, research and development policy for Spiny Lobster fisheries. Report U.N. Development Program FAO, TA 2481 :i-xii, 1-86, figs 1-15 Arana Espina, P. & C.A. Melo Urrutia, 1973. Pesca comercial’de Jasus frontalis en las Islas Robinson Crusoe y Santa Clara. (1971-1972). La Langosta de Juan Fernández II. Investigaciones Marinas, Valparaiso, 4(5):135-152, figs 1-5. For no. I see next item, for III see Pizarro et al., 1974, for IV see Pavez Carrera et al., 1974 Arana Espina, P.