Atoll Research Bulletin No. 505

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Committee Attachments Wednesday, 17 August 2016

Committee Attachments Wednesday, 17 August 2016 REPORT PAGE REPORT TITLE AND ATTACHMENT DESCRIPTION NUMBER NUMBER(S) 10.1 Chittering Bushfire Advisory Committee – 12 July 2016 1 – 47 1. “Unconfirmed” draft minutes of the Chittering Bush Fire Advisory Committee meeting held on Tuesday, 12 July 2016 2. The Constitution of the Chittering Fire Service 10.2 Audit Committee – 9 August 2016 48 – 80 1. “Unconfirmed” minutes of the Audit Committee meeting held on 4 February 2015 2. Proposal from Moore Stephens Item 10.1 - Attachment 1 MINUTES OF THE CHITTERING BUSH FIRE ADVISORY COMMITTEE TUESDAY, 12 JULY 2016 Council Chambers 6177 Great Northern Highway Bindoon Commencement: 7.05pm Closure: 8.05pm Page 1 Item 10.1 - Attachment 1 These minutes will be confirmed at the Chittering Bushfire Advisory Committee to be held on 11 October 2016. SIGNED BY _____________________________________ Person presiding at the meeting at which minutes were confirmed DATE _____________________________________ Disclaimer The purpose of this Council meeting is to discuss and, where possible, make resolutions about items appearing on the agenda. Whilst Council has the power to resolve such items and may in fact, appear to have done so at the meeting, no person should rely on or act on the basis of such decision or on any advice or information provided by a member or officer, or on the content of any discussion occurring, during the course of the meeting. Persons should be aware that the provisions of the Local Government Act 1995 (section 5.25 (e)) establish procedures for revocation or rescission of a Council decision. No person should rely on the decisions made by Council until formal advice of the Council decision is received by that person. -

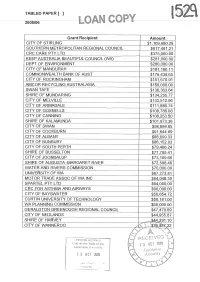

Tabled Paper [I

TABLED PAPER [I 2005/06 Grant Recipient Amount CITY OF STIRLING 1,109,680.28 SOUTHERN METROPOLITAN REGIONAL COUNCIL $617,461.21 CRC CARE PTY LTD $375,000.00 KEEP AUSTRALIA BEAUTIFUL COUNCIL (WA) $281,000.00 DEPT OF ENVIRONMENT $280,000.00 ITY OF MANDURAH $181,160.11 COMMONWEALTH BANK OF AUST $176,438.65 CITY OF ROCKINGHAM $151,670.91 AMCOR RECYCLING AUSTRALASIA 50,000.00 SWAN TAFE $136,363.64 SHIRE OF MUNDARING $134,255.77 CITY OF MELVILLE $133,512.96 CITY OF ARMADALE $111,880.74 CITY OF GOSNE LS $108,786.08 CITY OF CANNING $108,253.50 SHIRE OF KALAMUNDA $101,973.36 CITY OF SWAN $98,684.85 CITY OF COCKBURN $91,644.69 CITY OF ALBANY $88,699.33 CITY OF BUNBURY $86,152.03 CITY OF SOUTH PERTH $79,466.24 SHIRE OF BUSSELTON $77,795.41 CITY OF JOONDALUP $73,109.66 SHIRE OF AUGUSTA -MARGARET RIVER $72,598.46 WATER AND RIVERS COMMISSION $70,000.00 UNIVERSITY OF WA $67,272.81 MOTOR TRADE ASSOC OF WA INC $64,048.30 SPARTEL PTY LTD $64,000.00 CRC FOR ASTHMA AND AIRWAYS $60,000.00 CITY OF BAYSWATER $50,654.72 CURTIN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY $50,181.00 WA PLANNING COMMISSION $50.000.00 GERALDTON GREENOUGH REGIONAL COUN $47,470.69 CITY OF NEDLANDS $44,955.87_ SHIRE OF HARVEY $44,291 10 CITY OF WANNEROO 1392527_ 22 I Il 2 Grant Recisien Amount SHIRE OF MURRAY $35,837.78 MURDOCH UNIVERSITY $35,629.83 TOWN OF KWINANA $35,475.52 PRINTING INDUSTRIES ASSOCIATION $34,090.91 HOUSING INDUSTRY ASSOCIATION $33,986.00 GERALDTON-GREENOUGH REGIONAL COUNCIL $32,844.67 CITY OF FREMANTLE $32,766.43 SHIRE OF MANJIMUP $32,646.00 TOWN OF CAMBRIDGE $32,414.72 WA LOCAL GOVERNMENT -

NOTICE of MEETING Elected Members

NOTICE OF MEETING Elected Members Please be advised that the next Ordinary Meeting of Council will be held in Council Chambers, Home Island on Wednesday, 25 March 2020 commencing at 4.00pm. Andrea Selvey Chief Executive Officer DISCLAIMER The advice and information contained herein is given by and to the Council without liability or responsibility for its accuracy. Before placing any reliance on this advice or information, a written inquiry should be made to the Council giving entire reasons for seeking the advice or information and how it is proposed to be used. Please note this agenda contains recommendations which have not yet been adopted by Council. Members of the public should note that in any discussion regarding any planning or other application that any statement or intimation of approval made by any member or officer of the Shire during the course of any meeting is not intended to be and is not to be taken as notice of approval from the Shire. No action should be taken on any item discussed at a Council meeting prior to written advice on the resolution of the Council being received. Any plans or documents contained in this document may be subject to copyright law provisions (Copyright Act 1968, as amended) and the express permission of the copyright owner(s) should be sought prior to the reproduction. PO Box 1094, Home Island, Cocos (Keeling) Islands INDIAN OCEAN 6799 Tel: (08) 9162 6649 Fax:(08) 9162 6668 Email: [email protected] AGENDA OF THE ORDINARY MEETING OF COUNCIL 25 MARCH 2020 OUR VALUES Service Provide the best service we can. -

Agenda Attachments

Agenda Attachments July 2018 ATTACHMENT 7.1.1 PREVIOUS ORDINARY COUNCIL MEETING MINUTES ATTACHMENT 7.2.1. CENTRAL COUNTRY ZONE MEETING MINUTES ATTACHMENT 7.2.2 CENTRAL COUNTRY ZONE SPECIAL EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE MEETING MINUTES ATTACHMENT 7.2.3 ROE TOURISM ASSOCIATION MEETING MINUTES ATTACHMENT 8.1.2 ACCOUNTS FOR PAYMENT – JUNE 2018 ATTACHMENT 8.1.3 ACCOUNTS FOR PAYMENT – CREDIT CARDS ATTACHMENT 8.1.4 MONTHLY FINANCIALS – JUNE 2018 (Attachment provided seperately) ATTACHMENT 8.1.5 PROPOSED SCHEDULE OF FEES AND CHARGES 2018/19 (Attachment provided seperately) ATTACHMENT 8.2.1 REVISED CORPORATE BUSINESS PLAN ATTACHMENT 8.2.2 REVISED WORKFORCE PLAN ATTACHMENT 15.1 AGENDA WALGA AGM 2018 MINUTES ORDINARY COUNCIL MEETING TUESDAY 19 JUNE 2018 Strengthening our community now to grow and prosper into the future THIS DOCUMENT CAN BE MADE AVAILABLE (ON REQUEST) IN OTHER FORMATS FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITY Minutes - Ordinary Council Meeting – Tuesday 19 June 2018 CONTENTS 1 DECLARATION OF OPENING ........................................................................................................................................ 3 2 ATTENDANCE/APOLOGIES/LEAVE OF ABSENCE ...................................................................................................... 3 3 PUBLIC QUESTION TIME ............................................................................................................................................... 3 4 MEMORIALS ................................................................................................................................................................... -

Gazette 103 of 2021

Original Document Creator: Bruce Smith WESTERN 2111 AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT ISSN 1448-949X (print) ISSN 2204-4264 (online) PRINT POST APPROVED PP665002/00041 PERTH, TUESDAY, 15 JUNE 2021 No. 103 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY GEOFF O. LAWN, GOVERNMENT PRINTER © STATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA CONTENTS PART 1 Page City of Gosnells—Standing Orders Amendment Local Law 2021 ........................................... 2113 Workers’ Compensation and Injury Management (Section 10) Notice 2021 ........................... 2114 ——— PART 2 Fire and Emergency Services .................................................................................................... 2115 Health ......................................................................................................................................... 2118 Justice ......................................................................................................................................... 2118 Local Government ...................................................................................................................... 2119 Planning ..................................................................................................................................... 2119 Public Notices ............................................................................................................................. 2121 IMPORTANT COPYRIGHT NOTICE © State of Western Australia This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by -

Western Councillor ISSUE 104 | OCT/NOV 2019

Western Councillor ISSUE 104 | OCT/NOV 2019 COASTAL RISE BUSSELTON P06 MANAGEMENT PLANNING P09 DIRECT FLIGHTS Local governments working together. At LGIS, protecting our local government members is what we do. We make sure our members have the right cover to suit their needs. If disaster strikes, our local government specialists help get them, and their community, back on their feet as soon as possible. It’s our members who make Western Australia such a great place to live – their roads get us around, we meet in their libraries and recreation centres, they manage our waste, and provide connection for the elderly. Every day they provide the countless services and support which makes us a community. We believe that’s worth protecting. To find out how you can get the most out of your LGIS membership, visit lgiswa.com.au or call 9483 8888. LOCAL GOVERNMENT Peer Support Team BRINGING CLARITY TO A practical way to provide mediation and conciliation support to Local Governments COMPLEXITY in Western Australia. The Peer Support Team is of confl ict and reduce the need for an initiative between the WA formal investigations or enquiries. The team will meet with the affected Australia’s Local Government sector. Local Government Association (WALGA) and Local Government Councillors and staff individually, as Our team of highly experienced lawyers strive for clarity and well as in a group setting, allowing Professionals WA. excellence in our legal advice to our clients. all parties to freely express their The team was formed to provide views in a neutral environment. conciliation, negotiation and The team will then assist the Local manage and solve the legal issues that face your Local mediation support to Local Government to develop outcomes Government. -

Agenda Audit Committee Meeting 16 November 2016

Agenda Audit Committee Meeting 16 November 2016 Notice of an Audit Committee Meeting The next Audit Committee Meeting of the Shire of Coorow will be held on Wednesday 16 November 2016, at the Leeman Recreation Centre, from 4.30pm. Peter Crispin Chief Executive Officer Agenda for Audit Committee Meeting to be held Wednesday 16 November 2016 Page 1 DISCLAIMER No responsibility whatsoever is implied or accepted by Shire of Coorow for any act, omission or statement or intimation occurring during Council/Committee meetings or during formal/informal conversations with Staff. Shire of Coorow disclaims any liability for any loss whatsoever and howsoever caused arising out of reliance by any person or legal entity on any such act, omission or statement or intimation occurring during Council/Committee meetings or discussions. Any person or legal entity who acts or fails to act in reliance upon any statement does so at that person's or legal entity's own risk. In particular and without derogating in any way from the broad disclaimer above, in any discussion regarding any planning application or application for a licence, any statement or limitation of approval made by a member or officer of Shire of Coorow during the course of any meeting is not intended to be and is not taken as notice of approval from Shire of Coorow. The Shire of Coorow warns that anyone who has an application lodged with Shire of Coorow must obtain and only should rely on WRITTEN CONFIRMATION of the outcome of the application, and any conditions attaching to the decision made by the Shire of Coorow in respect of the application. -

Minutes of Kimberley Regional Group

JOINT MEETING OF THE KIMBERLEY ZONE OF WALGA AND KIMBERLEY REGIONAL GROUP UNCONFIRMED MINUTES 3:30PM, 3 SEPTEMBER 2018 Council Chambers, Shire of Wyndham East Kimberley, Kununurra Minutes – Kimberley Regional Group 3 September 2018 Page 2 of 31 SHIRE OF BROOME KIMBERLEY REGIONAL GROUP MONDAY 3 SEPTEMBER 2018 INDEX – MINUTES 1. DECLARATION OF OPENING / ANNOUNCEMENT OF VISITORS ...................................... 3 2. RECORD OF ATTENDANCE / APOLOGIES ......................................................................... 3 3. DECLARATION OF INTERESTS ............................................................................................... 4 4. CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES .............................................................................................. 4 5. BUSINESS ARISING FROM PREVIOUS MEETING .................................................................. 4 6. PRESENTATIONS FROM REPRESENTATIVES.......................................................................... 4 7. REPORTS FROM REPRESENTATIVES ...................................................................................... 5 8. REPORTS FROM KIMBERLEY COUNTRY ZONE .................................................................... 6 8.1 STATE COUNCIL MEETING AGENDA AND PRESIDENT'S REPORT SEPTEMBER 2018 .............................................................................................................................. 6 9. REPORTS FROM KIMBERLEY REGIONAL GROUP ............................................................. 18 9.1 2018/19 KIMBERLEY -

Regional Climate Alliance Program Expression of Interest to Form a Climate Alliance Application Guidelines

Regional Climate Alliance Program Expression of Interest to Form a Climate Alliance Application Guidelines May 2021 Image: Denmark Inlet (Source: WALGA) [email protected] www.walga.asn.au 08 9213 2000 Acknowledgement The WA Local Government Association (WALGA) acknowledges the Traditional Owners of the land and pays respects to Elders past, present and emerging. Image: ‘Untitled’ (Derbari Yerrigan-Swan River)’ by Jade Orchid Dolman Penangke (Source: WALGA) Regional Climate Alliance Program-Application Guidelines Contents Introduction 2 Program overview 6 Purpose of the Program 6 Program Funding 6 Regional Climate Alliance Coordinator Position 7 Regional Climate Alliance Project Funding 7 Eligibility Criteria 8 Program Timeframes 10 How to apply 11 Advice and guidance 11 Assessment 12 Assessment Criteria 12 The Application and Assessment Process 12 Notification of assessment outcome 13 Key dates 13 Requirements for successful recipients 14 Program launch and promotion 14 Alliance Funding Agreement with WALGA 14 Project management 14 Payment of funding 14 Progress reporting 15 Program completion and evaluation 15 Legislative and Regulatory Requirements 16 Tax Implications 16 Acknowledging the State Government and WALGA’s support 16 Insurance requirements 16 Disclaimer 17 Privacy policy 17 References 17 Introduction The Western Australian Local Government Association (WALGA) is inviting Local Governments to submit an Expression of Interest to establish a climate alliance under the Regional Climate Alliance Program. The Program is an initiative under the State Government’s Western Australian Climate Policy and aims to support regional Local Governments to take action on climate change, energy and sustainability through regional partnerships. The Department of Water and Environmental Regulation (DWER), the lead agency for the initiative, has partnered with WALGA to administer the Program. -

Interpretation Plan for the Shire of Cocos (Keeling) Islands

Interpretation Plan for the Shire of Cocos (Keeling) Islands Paul Bridges & Val Humphrey in association with Denise Cook September 2008 Title page image, opposite: The end of the Jukong race, October 2007 Home Island, 1987 Cover images: Jukong race winner, October 2007 School tour dancers, April 2007 Aerial mosaic image of Direction, Prison and Home Islands, 1987 Sections also used on title page and Figures 5,6,7 and 8. Courtesy of United Photo & Graphic Services www.unitedphoto.com.au T: (03) 9877 3922 Interpretation Plan for the Shire of Cocos (Keeling) Islands A guide to telling the stories of the people and places of the Cocos Islands, for the benefit of visitors and for future generations of the community, using the Copra Industrial Precinct as the hub. Paul Bridges & Val Humphrey in association with Denise Cook September 2008 Cocos (Keeling) Islands – Interpretation Plan 2008 Wedding of Jumanie and Jalfaizal, May 2007 Interpretation Plan for the Shire of Cocos (Keeling) Islands Part I: Project overview ..................................................................1 1. Acknowledgements................................................................................. 1 2. Executive Summary ................................................................................ 3 2.1 Background 3 2.2 Purpose 3 2.3 Key Themes 3 2.4 Implementation of the Interpretation Plan 4 3. Staging Plan & List of Recommendations................................................... 6 3.1 Stages of implementation and indicative costs 6 3.2 List of Recommendations -

Our Strategic Plan

Our tools Robust, efficient, user-friendly, flexible, agile, reliant, compliant Outcomes Strategies Efficient, effective • Work within a framework and governance structure and responsive which is current and effective business • Respond effectively to changes in our environment by operations that maintaining a strategic focus meet current and • Maintain an appropriate and effective approach to risk emerging needs management • Ensure accurate and reliable technical advice is available Sound information • Ensure IT systems are efficient, effective and systems supported that support • Capitalise where possible on our existing systems to operational needs improve our business operations • Have an approach to IT that recognises and addresses operational and strategic business requirements • Continuously improve internal and external accessibility and useability of our tools Sound financial • Maintain a strong, sound and transparent financial management of management approach our business • Use accurate business data that informs management decision-making • Continuously improve our processes to ensure qual- ity and compliance of internal financial management practices Audit methodology • Ensure our methodology remains current and tools are current, compliant reliable and compliant Appendix 1: Our strategic plan As this is the final year of the OAG Strategic Plan 2016-2020, our Executive will finalise a new 5-year strategic plan by the end of 2020. Our people Motivated, innovative, collaborative, accountable, valued, skilled, Our tools knowledgeable -

Minutes Ordinary Meeting of Council 31 March 2021, 4.00Pm Council Chambers, Home Island

Shire of Cocos (Keeling) Islands Shire of Cocos (Keeling) Islands Minutes Ordinary Meeting of Council 31 March 2021, 4.00pm Council Chambers, Home Island MINUTES OF THE ORDINARY MEETING OF COUNCIL 31 MARCH 2021 OUR VALUES Service Provide the best service we can. We serve the community and each other. Accountability We take responsibility for our own actions. We do what we say we will do. Mistakes are an opportunity to learn. Support We support our team and our community. Look for opportunities to help each other. Respect We respect and value others. Our interactions are always respectful towards others. Integrity We will be honest and transparent with all our dealings. Maintain confidentiality. Trust each other. Achievement Being proactive and enabling the outcomes. Be creative and think outside the square. 1 | P a g e MINUTES OF THE ORDINARY MEETING OF COUNCIL 31 MARCH 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 OPENING/ANNOUNCEMENTS OF VISITORS 4 2 ATTENDANCE/APOLOGIES/LEAVE OF ABSENCE (PREVIOUSLY APPROVED) 4 3 RESPONSE TO PREVIOUS PUBLIC QUESTIONS TAKEN ON NOTICE 4 4 PUBLIC QUESTION TIME 5 5 LEAVE OF ABSENCE 5 5.1 LEAVE OF ABSENCE (PREVIOUSLY APPROVED) 6 5.2 APPLICATION FOR LEAVE OF ABSENCE 6 6 PETITIONS/DEPUTATIONS/PRESENTATIONS 6 7 CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES OF PREVIOUS MEETINGS 6 7.1 ORDINARY COUNCIL MEETING HELD ON 24 FEBRUARY 2021 6 8 ANNOUNCEMENTS BY THE PRESIDING MEMBER AND COUNCILLORS 7 9 DECLARATION OF INTERESTS 7 10 REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS 7 REPORTS OF OFFICERS AND RECOMMENDATIONS OF COMMITTEE 7 10.1 FINANCE 7 10.1.1 MONTHLY STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL ACTIVITY FOR THE MONTH ENDING 28 7 FEBRUARY 2021 10.1.2 SCHEDULE OF ACCOUNTS PAID FOR PERIOD 1 FEBRUARY 2021 TO 28 FEBRUARY 11 2021 10.2.