A Handy Man's Guide to Copyright Infringement: Standing, Public Domain and Registration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

WDAM Radio's History of Peter & Gordon

WDAM Radio's Hit Singles History Of Peter & Gordon # Artist Title Chart Position/Year Comments 01 Peter & Gordon “A World Without Love” #1-U.S. + #1-U.K., Paul McCartney – composer. Credited to John Canada, Ireland, New Lennon & Paul McCartney. Zealand & #2-Australia & #8 in Norway/1964 01A Bobby Rydell “A World Without Love” #80/1964 (#1-Philadelphia Debuted 5/9/1964 – the same date as Peter & & #10 in Chicago) + #5- Gordon’s version. Singapore & #9-Hong Kong. 01B Supremes “A World Without Love” #7-Maylasia/1964 02 Peter & Gordon “Nobody I Know” #12-U.S. + #10-U.K./1964 John Lennon & Paul McCartney – composers. 03 Peter & Gordon “I Don’t Want To See You Again” #16/1964 John Lennon & Paul McCartney – composers. 04 Peter & Gordon “I Go To Pieces” #9-U.S. + #21-Canada, Del Shannon – composer. A-side. #11-Sweden & #26- Australia/1964 04 Lloyd Brown “I Go To Pieces” –/1965 Del Shannon – composer, producer, and second voice harmony. 04B Del Shannon “I Go To Pieces" –/1965 . 05 Peter & Gordon “Love Me Baby” #26-Australia/1964 B-side. 06 Peter & Gordon “True Love Ways” #14-U.S. + #32-U.K./1965 Buddy Holly & Norman Petty – composers, 06A Buddy Holly (& The “True Love Ways” #25-U.K./1960 & #65- Dick Jacobs U.K./1988 Orchestra) 07 Peter & Gordon “To Know You Is To Love You” #24-U.S. + #5-U.K./1965 Phil Spector – composer. 07A Teddy Bears “To Know Him Is To Love Him” #1-U.S. + #2-U.K./1958 & #66-U.K./1979 08 Peter & Gordon “Baby I’m Yours” #19-U.K./1965 08A Barbara Lewis “Baby I’m Yours” #11-Rock & #5-R&B-U.S. -

Sound Recording in the British Folk Revival: Ideology, Discourse and Practice, 1950–1975

Sound recording in the British folk revival: ideology, discourse and practice, 1950–1975 Matthew Ord Submitted in fulfilment of the degree of PhD International Centre for Music Studies Newcastle University March 2017 Abstract Although recent work in record production studies has advanced scholarly understandings of the contribution of sound recording to musical and social meaning, folk revival scholarship in Britain has yet to benefit from these insights. The revival’s recording practice took in a range of approaches and contexts including radio documentary, commercial studio productions and amateur field recordings. This thesis considers how these practices were mediated by revivalist beliefs and values, how recording was represented in revivalist discourse, and how its semiotic resources were incorporated into multimodal discourses about music, technology and traditional culture. Chapters 1 and 2 consider the role of recording in revivalist constructions of traditional culture and working class communities, contrasting the documentary realism of Topic’s single-mic field recordings with the consciously avant-garde style of the BBC’s Radio Ballads. The remaining three chapters explore how the sound of recorded folk was shaped by a mutually constitutive dialogue with popular music, with recordings constructing traditional performance as an authentic social practice in opposition to an Americanised studio sound equated with commercial/technological mediation. As the discourse of progressive rock elevated recording to an art practice associated with the global counterculture, however, opportunities arose for the incorporation of rock studio techniques in the interpretation of traditional song in the hybrid genre of folk-rock. Changes in studio practice and technical experiments with the semiotics of recorded sound experiments form the subject of the final two chapters. -

BBC 4 Listings for 5 – 11 June 2021 Page 1 of 4

BBC 4 Listings for 5 – 11 June 2021 Page 1 of 4 SATURDAY 05 JUNE 2021 Sarah and Jan are convinced that there is a link between fashion and hip-hop scenes that have fed off historic power Nanna's murder and an unsolved case from 15 years earlier. It is struggles and culture clashes, both between ancient empires and SAT 19:00 How the Celts Saved Britain (b00ktrby) now a race against time to nail the evidence. Pernille and Theis against French colonisers. She traces the story of Leopold Salvation are puzzled as they realise the case is far from closed. Troels is Senghor, a poet who became the father of Senegalese counting on winning the election and is willing to put everything independence and redefined what Africa is. She explores cities Provocative two-part documentary in which Dan Snow blows on the line. with exuberant murals and street culture that respond to the the lid on the traditional Anglo-centric view of history and past, and she meets internationally acclaimed choreographer reveals how the Irish saved Britain from cultural oblivion during Germaine Acogny, griot musician Diabel Cissokho and hip-hop the Dark Ages. SAT 00:45 The Killing (b00zth0c) legend DJ Awadi. Series 1 He follows in the footsteps of Ireland's earliest missionaries as they venture through treacherous barbarian territory to bring Episode 18 SUN 23:00 Searching for Shergar (b0b623r9) literacy and technology to the future nations of Scotland and The story of one of the world's most valuable racehorses, England. Sarah and Jan check out an abandoned warehouse to look for Shergar, who disappeared in 1983 at the height of the Troubles. -

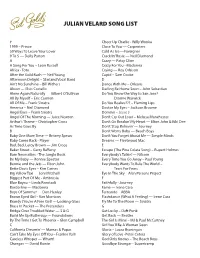

Julian Velard Song List

JULIAN VELARD SONG LIST # Cheer Up Charlie - Willy Wonka 1999 – Prince Close To You — Carpenters 50 Ways To Leave Your Lover Cold As Ice —Foreigner 9 To 5 — Dolly Parton Cracklin’ Rosie — Neil Diamond A Crazy — Patsy Cline A Song For You – Leon Russell Crazy For You - Madonna Africa - Toto Crying — Roy Orbison After the Gold Rush — Neil Young Cupid – Sam Cooke Afternoon Delight – Starland Vocal Band D Ain’t No Sunshine – Bill Withers Dance With Me – Orleans Alison — Elvis Costello Darling Be Home Soon – John Sebastian Alone Again Naturally — Gilbert O’Sullivan Do You Know the Way to San Jose? — All By Myself – Eric Carmen Dionne Warwick All Of Me – Frank Sinatra Do You Realize??? – Flaming Lips America – Neil Diamond Doctor My Eyes – Jackson Browne Angel Eyes – Frank Sinatra Domino – Jesse J Angel Of The Morning — Juice Newton Don’t Cry Out Loud – Melissa Manchester Arthur’s Theme – Christopher Cross Don’t Go Breakin’ My Heart — Elton John & Kiki Dee As Time Goes By Don’t Stop Believin’ — Journey B Don’t Worry Baby — Beach Boys Baby One More Time — Britney Spears Don’t You Forget About Me — Simple Minds Baby Come Back - Player Dreams — Fleetwood Mac Bad, Bad, Leroy Brown — Jim Croce E Baker Street – Gerry Raerty Escape (The Pina Colata Song) – Rupert Holmes Bare Necessities - The Jungle Book Everybody’s Talkin’ — Nilsson Be My Baby — Ronnie Spector Every Time You Go Away – Paul Young Bennie and the Jets — Elton John Everybody Wants To Rule The World – Bette Davis Eyes – Kim Carnes Tears For Fears Big Yellow Taxi — Joni Mitchell Eye In -

James Taylor

JAMES TAYLOR Over the course of his long career, James Taylor has earned 40 gold, platinum and multi- platinum awards for a catalog running from 1970’s Sweet Baby James to his Grammy Award-winning efforts Hourglass (1997) and October Road (2002). Taylor’s first Greatest Hits album earned him the RIAA’s elite Diamond Award, given for sales in excess of 10 million units in the United States. For his accomplishments, James Taylor was honored with the 1998 Century Award, Billboard magazine’s highest accolade, bestowed for distinguished creative achievement. The year 2000 saw his induction into both the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame and the prestigious Songwriter’s Hall of Fame. In 2007 he was nominated for a Grammy Award for James Taylor at Christmas. In 2008 Taylor garnered another Emmy nomination for One Man Band album. Raised in North Carolina, Taylor now lives in western Massachusetts. He has sold some 35 million albums throughout his career, which began back in 1968 when he was signed by Peter Asher to the Beatles’ Apple Records. The album James Taylor was his first and only solo effort for Apple, which came a year after his first working experience with Danny Kortchmar and the band Flying Machine. It was only a matter of time before Taylor would make his mark. Above all, there are the songs: “Fire and Rain,” “Country Road,” “Something in The Way She Moves,” ”Mexico,” “Shower The People,” “Your Smiling Face,” “Carolina In My Mind,” “Sweet Baby James,” “Don’t Let Me Be Lonely Tonight,” “You Can Close Your Eyes,” “Walking Man,” “Never Die Young,” “Shed A Little Light,” “Copperline” and many more. -

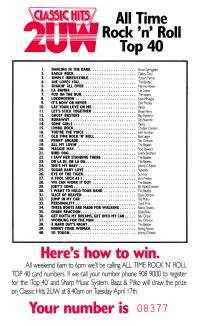

2UW All Time Rock'n'roll Top 40

All Time Rock 'n' Roll Top 40 I. DANCING IN THE DARK Bruce Springsteen 2. EAGLE ROCK Daddy Cool 3. SIMPLY IRRESISTIBLE Robert Palmer 4. SHE LOVES YOU The Beatles 5. SHAKIN' ALL OVER Normie Rowe 6. LA BAMBA Los Lobos 7. FOX ON THE RUN The Sweet 8. LOCOMOTION Kylie Minogue 9. IT'S NOW OR NEVER Elvis Presley 0. LAY YOUR LOVE ON ME Racey I. LET'S STICK TOGETHER Bryan Ferry 2. GHOST BUSTERS Ray Parker Jr 3. RUNAWAY Del Shannon 4. SOME GIRLS Racey S. LIMBO ROCK Chubby Checker 6. YOU'RE THE VOICE John Farnham 7. OLD TIME ROCK 'N' ROLL Bob Seger 8. PENNY ARCADE Roy Orbison 9. ALL MY LOVIN' The Beatles 20. MAGGIE MAY Rod Stewart 21. BIRD DOG Everly Brothers 22. I SAW HER STANDING THERE The Beatles 23. OB LA DI, OB LA DA The Beatles 24. SHE'S MY BABY Johnny O'Keefe 25. SUGAR BABY LOVE Rubettes 26. EYE OF THE TIGER Survivor 27. A FOOL SUCH AS I Elvis Presley 28. WE CAN WORK IT OUT The Beatles 29. JOEY'S SONG Bill Haley/Comets 30. I WANT TO HOLD YOUR HAND The Beatles 31. SLICE OF HEAVEN Dave Dobbyn 32. JUMP IN MY CAR Ted Mulry 33. PERSONALITY . Lloyd Price 34. THESE BOOTS ARE MADE FOR WALKING Nancy Sinatra 35. CHAIN REACTION Diana Ross 36. GET OUTTA MY DREAMS, GET INTO MY CAR Billy Ocean 37. WORKING FOR THE MAN Roy Orbison 38. A HARD DAY'S NIGHT The Beatles 39. HONKY TONK WOMAN Rolling Stones 40. -

Weißer Mann, Was Nun?

Freiburg · Mittwoch, 15. Januar 2020 http://www.badische-zeitung.de/weisser-mann-was-nun-die-tagung-queer-pop-in-freiburg Weißer Mann, was nun? Die Tagung „Queer Pop“ in Freiburg will nicht nur die Grenzen des Geschlechter-Denkens erweitern, sondern stellt dem Denken auch das Tanzen zur Seite F F O O T T O Als die Pet Shop Boys 1984 mit ihrem Al- ordnung als das Selbstverständnis quee- Unis Seminare zu Queer Pop stattgefun- O : : A C N bum „West End Girls“ ihre erfolgreichste rer Popstars wider, das immerzu chan- den, sondern die Party wird mit Perfor- H N R I E S T T T Zeit erlebten, waren sie noch Teil einer giert, sich neu erfindet und starres Scha- mances Studierender eröffnen, die quee- O E P K H O S schwul-lesbischen Subkultur, die sich in R blonen-Denken bewusst durchkreuzt. re Ästhetik auf die Bühne bringen. Dar- C O H L M Codes ausdrückte. Für das Publikum, das L Bei „Queer Pop“ geht es nicht nur um auf, wie auch heterosexuelle Menschen I D T sie an die Spitze der Charts hievte, stand Musik: Queere Strategien finden sich in sich queer inszenieren, darf man ge- ( D P A die geschlechtliche Identität der Musiker allen medialen Bereichen, vom Film über spannt sein, doch weist diese Frage auch ) zumindest nicht im Vordergrund. Anders Literatur und Mode bis zur Kunst und auf einen anderen Umstand hin: Queeres war das bei Boy George und seiner Band Fotografie. „Wir wollen uns mit queerer Denken hat sich von der reinen Auseinan- Culture Club, die etwa zur gleichen Zeit Ästhetik beschäftigen, aber auch aufzei- dersetzung mit Genderrollen hin zu durch ihr androgynes Auftreten zu welt- gen, wie diese inzwischen Diskussionen grundlegenden sozialkritischen Fragen weiten Pop-Ikonen wurden. -

Easy Listening/ Jazz/ Oldies/ Reggae

EASY LISTENING/ JAZZ/ OLDIES/ REGGAE Make You Feel My Love- Adele Lost In Love- Air Supply A Song For My Daughter- Ray Allaire Horse With No Name- America Sister Golden Hair- America Ventura Highway- America You Can Do Magic- America What A Wonderful World- Louis Armstrong So Into You- Atlanta Rhythm Section Islands In The Stream- The Bee Gees/ Kenny Rogers I’ve Gotta Get A Message To You- The Bee Gees To Love Somebody- The Bee Gees Let Your Love Flow- Bellamy Brothers You’re Beautiful- James Blunt A Mother’s Love- Jim Brickman Running On Empty- Jackson Browne Somebody’s Baby- Jackson Browne Everything- Michael Buble Hallelujah- Jeff Buckley Changes In Latitudes, Changes In Attitudes- Jimmy Buffett Cheeseburger In Paradise- Jimmy Buffett Come Monday- Jimmy Buffett Fins- Jimmy Buffett Little Miss Magic- Jimmy Buffett Margaritaville- Jimmy Buffett A Pirate Looks At 40- Jimmy Buffett Volcano- Jimmy Buffett Why Don’t We Get Drunk- Jimmy Buffett Brighter Than The Sun- Colbie Calliat Bubbly- Colbie Calliat I Do- Colbie Calliat Butterfly Kisses- Bob Carlisle In Your Eyes- David Chamberlain Cats In The Cradle- Harry Chapin Cinderella- Steven Curtis Chapman We Will Dance- Steven Curtis Chapman EASY LISTENING/ JAZZ/ OLDIES/ REGGAE Fast Car- Tracy Chapman Give Me One Reason- Tracy Chapman Georgia On My Mind- Ray Charles I Can See Clearly Now- Jimmy Cliff I Love You- Climax Blues Band You Are So Beautiful- Joe Cocker Walking In Memphis- Marc Cohn Unforgettable- Nat King Cole Against All Odds- Phil Collins A Groovy Kind Of Love- Phil Collins You Can’t -

1 THERESA WERNER: (Sounds Gavel.) Good Afternoon, and Welcome to the National Press Club. My Name Is Theresa Werner, and I Am T

NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LUNCHEON WITH JAMES TAYLOR SUBJECT: ELECTION REFORM: LIFE AS A POLITICAL SURROGATE MODERATOR: THERESA WERNER, PRESIDENT, NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LOCATION: NATIONAL PRESS CLUB BALLROOM, WASHINGTON, D.C. TIME: 12:30 P.M. EDT DATE: FRIDAY, DECEMBER 7, 2012 (C) COPYRIGHT 2008, NATIONAL PRESS CLUB, 529 14TH STREET, WASHINGTON, DC - 20045, USA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ANY REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION IS EXPRESSLY PROHIBITED. UNAUTHORIZED REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION CONSTITUTES A MISAPPROPRIATION UNDER APPLICABLE UNFAIR COMPETITION LAW, AND THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB RESERVES THE RIGHT TO PURSUE ALL REMEDIES AVAILABLE TO IT IN RESPECT TO SUCH MISAPPROPRIATION. FOR INFORMATION ON BECOMING A MEMBER OF THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB, PLEASE CALL 202-662-7505. THERESA WERNER: (Sounds gavel.) Good afternoon, and welcome to the National Press Club. My name is Theresa Werner, and I am the 105th President of the National Press Club. We are the world’s leading professional organization for journalists committed to our profession’s future through our programming and events such as this while fostering a free press worldwide. For more information about the National Press Club, please visit our website, www.press.org. To donate to programs offered to the public through our National Press Club Journalism Institute, please visit press.org/institute. On behalf of our members worldwide, I'd like to welcome our speaker and those of you attending today’s event. Our head table includes guests of our speaker as well as working journalists who are National Press Club members. And if you hear applause in our audience, we would note that members of the general public are attending so it is not necessarily a lack of journalistic objectivity. -

Top 10 Songs of 1960 Top 10 Songs of 1961 Top 10 Songs of 1962 Top

Top 10 Songs of 1960 1. Will You Love Me Tomorrow - Shirelles 2. Georgia On My Mind - Ray Charles 3. Only The Lonely - Roy Orbison 4. Let's Go, Let's Go, Let's Go - Hank Ballard & the Midnighters 5. Stay - Maurice Williams & the Zodiacs 6. Chain Gang - Sam Cooke 7. Save The Last Dance For Me - Drifters 8. Shop Around - Miracles 9. The Twist - Chubby Checker 10. Cathy's Clown - Everly Brothers Top 10 Songs of 1961 1. Stand By Me - Ben E. King 2. Crazy - Patsy Cline 3. The Wanderer - Dion 4. Runaround Sue - Dion 5. Crying - Roy Orbison 6. Hit The Road Jack - Ray Charles 7. Runaway - Del Shannon 8. Quarter To Three - Gary U.S. Bonds 9. It Will Stand - Showmen 10. Running Scared - Roy Orbison Top 10 Songs of 1962 1. Green Onions - Booker T. & the MG's 2. Bring It On Home To Me - Sam Cooke 3. You've Really Got A Hold On Me - Miracles 4. The Loco-Motion - Little Eva 5. Sherry - Four Seasons 6. I Can't Stop Loving You - Ray Charles 7. Up On The Roof - Drifters 8. Twist And Shout - Isley Brothers 9. These Arms Of Mine - Otis Redding 10. Do You Love Me - Contours Top 10 Songs of 1963 1. Louie Louie - Kingsmen 2. She Loves You - Beatles 3. I Want To Hold Your Hand - Beatles 4. Be My Baby - Ronettes 5. I Saw Her Standing There - Beatles 6. Surfin' USA - Beach Boys 7. Glad All Over - Dave Clark Five 8. It's All Right - Impressions 9. Blowin' In The Wind - Bob Dylan / Peter Paul & Mary 10. -

Otis Blackwell: Songwriter to “The King”

Country Music Hall of Fame® and Museum • Words & Music • Grades 3-6 Otis Blackwell: Songwriter to “The King” As the songwriter of two of Elvis Presley’s career-making hits, Otis Blackwell will always be linked to the man known as the King of Rock & Roll. But so many artists have recorded Blackwell’s songs that his work reaches far beyond Presley’s shadow. The many hits Blackwell wrote made him one of rock & roll’s most influential songwriters. Born February 16, 1932, in Brooklyn, New York, Blackwell grew up next to a movie theater and developed a passion for Hollywood’s singing cowboys and their western music. “Like the blues, it told a story,” he once said. “But it didn’t have the same restrictive construction. A cowboy song could do anything.” Blackwell began writing songs in his teens, but turned his attention to performing after winning a local talent show. He soon tired of the road, however, choosing instead to focus on songwriting while working a day job pressing clothes at a New York tailor shop. Presley soon followed this success with “All Shook Up,” which Blackwell penned after his publisher shook a bottle of soda and Blackwell’s demo tape of “Don’t Be Cruel” caught the ear of jokingly challenged him to write a song about it. Presley, who was then looking to expand his popularity from the South to the nation as a whole. Taking cues from Blackwell’s vocal Building on his early success, Blackwell continued to write phrasing, Presley turned the song into a 1956 sensation that topped for Presley, and he created a string of hit songs for other the country, R&B, and pop charts alike.