Jantar Mantar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

Walker's Point Strategic Action Plan MILWAUKEE

MILWAUKEE comprehensive Department of City Development Plan • June, 2015 Walker’s Point Strategic Action Plan A Plan for the Area ii Acknowledgments Neighborhood Associations and Continuum Architects + Planners Interest Groups Ursula Twombly, AIA, LEED AP Arts@Large Walker’s Point Association GRAEF The Mandel Group Greater Milwaukee Committee Larry Witzling, Principal The Harbor District Initiative Craig Huebner, Planner/Urban Designer 12th District Alderman Jose Perez University of Wisconsin - Milwaukee Urban Development Studio City of Milwaukee Department of City Development Carolyn Esswein, AICP, CNU-A, Faculty Member in Charge Rocky Marcoux, Commissioner Vanessa Koster, Planning Manager Sam Leichtling, Long Range Planning Manager Mike Maierle, former Long Range Planning Manager Greg Patin, Strategic Planning Manager Dan Casanova, Economic Development Specialist Janet Grau, Plan Project Manager Nolan Zaroff, Senior Planner GIS, Eco- nomic Development Jeff Poellmann, Planning Intern (Urban Design) Andrew Falkenburg, Planning Intern (GIS/Mapping, Editing) City of Milwaukee Redevelopment Authority David Misky, Assistant Executive Director - Secretary Department of Public Works Mike Loughran, Special Projects Manager Walker’s Point Kristin Bennett, Bicycle Coordinator Strategic Action Plan Historic Preservation Carlen Hatala, Historic Preservation Principal Researcher iii Plan Advisory Group Sean Kiebzak, Arts@Large Juli Kaufmann, Fix Development Dan Adams, Harbor District Initiative Joe Klein, HKS/Junior House Dean Amhaus, Milwaukee Water Council Anthony A. LaCroix Nick & JoAnne Anton, La Perla Scott Luber, Independence First Samer Asad, Envy Nightclub Barry Mandel, The Mandel Group Luis “Tony” Baez, El Centro Hispano Megan & Tyler Mason, Wayward Kitchen Tricia M. Beckwith, Wangard Partners Robert Monnat, The Mandel Group Kristin Bennett, Bike Ped Coordinator Cristina Morales Brigette Breitenbach, Company B Lorna Mueller, The Realty Company, LLC Mike Brenner, Brenner Brewing Co. -

Fixed Fire Fighting and Emergency Ventilation Systems for Highway Tunnels – Literature Survey and Synthesis

FIXED FIRE FIGHTING AND EMERGENCY VENTILATION SYSTEMS FOR HIGHWAY TUNNELS – LITERATURE SURVEY AND SYNTHESIS FHWA-HIF-20-016 FFFS-EVS for Highway Tunnels – Literature Survey and Synthesis January 2020 Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. FHWA-HIF-20-016 TBA TBA 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Fixed Fire Fighting and Emergency Ventilation Systems January 2020 Literature Survey and Synthesis 6. Performing Organization Code TBA 7. Principal Investigator(s): 8. Performing Organization Bill Bergeson (FHWA), Matt Bilson (WSP), Bill Connell (WSP), Bobby Report Melvin (WSP), Katie McQuade-Jones (WSP) TBA 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) WSP USA, Inc. TBA One Penn Plaza th 250 West 34 Street 11. Contract or Grant No. New York, NY, 10119 DTFH6114D00048 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Federal Highway Administration Covered U.S. Department of Transportation TBA 1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE 14. Sponsoring Agency Code Washington, DC 20590 TBA 15. Supplementary Notes 16. Abstract There is a lot of global experience with fixed fire fighting systems in road tunnels, particularly in Australia and Japan, but also in several recently constructed tunnels in the United States and Europe. The U.S. first implemented FFFS in their tunnels in the 1950s, however, this approach did not become routine, partly due to unsuccessful tests of FFFS in the Offneg Tunnel in Europe. Because FFFS were not routinely applied in all tunnels, the present-day approach can vary between planned facilities and regions, especially in critical design areas such as operational integration with the emergency ventilation system (EVS). -

GERMAN IMMIGRANTS, AFRICAN AMERICANS, and the RECONSTRUCTION of CITIZENSHIP, 1865-1877 DISSERTATION Presented In

NEW CITIZENS: GERMAN IMMIGRANTS, AFRICAN AMERICANS, AND THE RECONSTRUCTION OF CITIZENSHIP, 1865-1877 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alison Clark Efford, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Doctoral Examination Committee: Professor John L. Brooke, Adviser Approved by Professor Mitchell Snay ____________________________ Adviser Professor Michael L. Benedict Department of History Graduate Program Professor Kevin Boyle ABSTRACT This work explores how German immigrants influenced the reshaping of American citizenship following the Civil War and emancipation. It takes a new approach to old questions: How did African American men achieve citizenship rights under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments? Why were those rights only inconsistently protected for over a century? German Americans had a distinctive effect on the outcome of Reconstruction because they contributed a significant number of votes to the ruling Republican Party, they remained sensitive to European events, and most of all, they were acutely conscious of their own status as new American citizens. Drawing on the rich yet largely untapped supply of German-language periodicals and correspondence in Missouri, Ohio, and Washington, D.C., I recover the debate over citizenship within the German-American public sphere and evaluate its national ramifications. Partisan, religious, and class differences colored how immigrants approached African American rights. Yet for all the divisions among German Americans, their collective response to the Revolutions of 1848 and the Franco-Prussian War and German unification in 1870 and 1871 left its mark on the opportunities and disappointments of Reconstruction. -

General Index

General Index Italic page numbers refer to illustrations. Authors are listed in ical Index. Manuscripts, maps, and charts are usually listed by this index only when their ideas or works are discussed; full title and author; occasionally they are listed under the city and listings of works as cited in this volume are in the Bibliograph- institution in which they are held. CAbbas I, Shah, 47, 63, 65, 67, 409 on South Asian world maps, 393 and Kacba, 191 "Jahangir Embracing Shah (Abbas" Abywn (Abiyun) al-Batriq (Apion the in Kitab-i balJriye, 232-33, 278-79 (painting), 408, 410, 515 Patriarch), 26 in Kitab ~urat ai-arc!, 169 cAbd ai-Karim al-Mi~ri, 54, 65 Accuracy in Nuzhat al-mushtaq, 169 cAbd al-Rabman Efendi, 68 of Arabic measurements of length of on Piri Re)is's world map, 270, 271 cAbd al-Rabman ibn Burhan al-Maw~ili, 54 degree, 181 in Ptolemy's Geography, 169 cAbdolazlz ibn CAbdolgani el-Erzincani, 225 of Bharat Kala Bhavan globe, 397 al-Qazwlni's world maps, 144 Abdur Rahim, map by, 411, 412, 413 of al-BlrunI's calculation of Ghazna's on South Asian world maps, 393, 394, 400 Abraham ben Meir ibn Ezra, 60 longitude, 188 in view of world landmass as bird, 90-91 Abu, Mount, Rajasthan of al-BlrunI's celestial mapping, 37 in Walters Deniz atlast, pl.23 on Jain triptych, 460 of globes in paintings, 409 n.36 Agapius (Mabbub) religious map of, 482-83 of al-Idrisi's sectional maps, 163 Kitab al- ~nwan, 17 Abo al-cAbbas Abmad ibn Abi cAbdallah of Islamic celestial globes, 46-47 Agnese, Battista, 279, 280, 282, 282-83 Mu\:lammad of Kitab-i ba/Jriye, 231, 233 Agnicayana, 308-9, 309 Kitab al-durar wa-al-yawaqft fi 11m of map of north-central India, 421, 422 Agra, 378 n.145, 403, 436, 448, 476-77 al-ra~d wa-al-mawaqft (Book of of maps in Gentil's atlas of Mughal Agrawala, V. -

Next Meeting on August14th MAS Picnic Solar Eclipse

July, 2017 Next Meeting on August14th The Milwaukee Astronomical Society will hold its next meeting on Monday, August 14h, from 7 PM at the Observatory. This is going to be a combined Board / Membership Meeting, where mostly organizational and Observatory related issues will be discussed. As always, the Observatory is open on Saturday nights, and also when it is posted Inside this on the Google Group. July meeting 1 MAS Picnic 1 MAS Picnic Solar Eclipse 1 Don’t forget about our annual picnic, which will th Meeting Minutes 2 be held on Saturday, August 5 at 4:00 PM at the Observatory. Come and join us, together with your Membership 2 family and friends. Treasurer Report 2 Please bring your favorite dish to pass. Beverages and charcoal grill will be provided. Observatory 2 Director‘s Report While enjoying the fellowship, you can take the opportunity to check out the modernized Quonset if Yerkes Star Party 3 you have not done so yet. Sun observation will also MAS Campout 4 be possible. See you there, in rain or shine! In the news 5 Adopt a Scope 6 Officers/Staff 6 Keyholders 6 Solar Eclipse The upcoming total solar eclipse on August 21st is easily the most anticipated astronomical event of the year. For many who get to view one of these, it becomes a life changing event. Some even go on to chase these eclipses throughout the world. Although our Club hosts certain astronomical events such as Mercury and Venus transits, lunar eclipses, we will not be holding an open house at the observatory on August 21st for the solar eclipse. -

Jantar Mantar Strike Seeks a Sustainable Earth

STUDENT PAPER OF TIMES SCHOOL OF MEDIA GREATER NOiDA | MONDAY, OCTOBER 14, 2019 | VOL 3 , ISSUE 8 | PAGES 8 THE TIMESOF BENNETT Exploring a slice of Tibet in Delhi Trophy from the hunt Hip-hop: culture over trends The ISAC Walk 1.0 : Glimpses of Geeta Bisht, BU’s front desk executive, on Rapper’s take on today’s the photowalk to Majnu-ka-tilla winning the Super Model Hunt 2019 hip-hop industry | Page 5 | Page 4 | Page 6 BU hosts 1st inter-college sports fest, Expedite 2019 Silent walks to By ASHIMA CHOUDHARY were soul-stirring. As the the yum eateries. Even Zardicate came together was one to remember. took trophies, cash mon- Bennett University con- audience and athletes Mrs. Pratima was thrilled to mellow down the stress The crowd lit up the night ey and hampers home! fight harassment ducted its first-ever came together, the event to see the level of enthu- from the tournaments. with grooving students The stir caused by sports fest from 27th to electrified the atmosphere. siasm shown by students. The first night ended with and radium accessories. the fest was palpable as 29th of September. It Food stalls, to source In her words, “I expect- a bonfire, relaxing every- The DJ night lasted well Yashraj Saxena, former welcomed 400 students everyone’s energy, were ed it to be chaotic, but one, but it was the 28th, into the hours. Everyone head of the committee, from 16 universities from voiced his words, “We’ve the Delhi NCR region, been trying to host this Jaipur, Gwalior and a for the past two years. -

Under the Arch

Summer, 1982 Hours of operation A free publication to May 29-September 6 provide information Visitor Center, 8:00 a.m. under about the Jefferson to 10:00 p.m. National Expansion Tram Ride, 8:30 a.m. to Memorial 9:30p.m. the Museum of Westward Expansion, 8:00 a.m. to 1arc h 10:00 p.m. Inside this GATEWAY ARCH: issue How long does it take to ride to the top? Where do I A Monument purchase tickets? These and other often asked questions are answered in "Riding to For Our Time the Top." The Museum of Westward Expansion recreates one of the country's most colorful eras. The next page provides a map of the museum and two articles that explain how to view it. See It Today May 29-September 6: Monument to the Dream, a 30-minute film, documents the construction of the Gateway Arch. Shows begin at 8:15 a.m., 9:15 a.m., 10:45 a.m., 12:15 p.m., 1:45 p.m., 2:30 p.m., 3:15 p.m., 4:45 •i p.m., 6:15 p.m., 7:45 p.m. and 8:45 p.m. in Tucker Theater adja i cent to the Gateway Arch lobby. Charles M. Russell: American Artist, a 20-minute film, interprets i the life and significance of a well- known artist of the West. Shows s begin at 10:00 a.m., 11:30 a.m., •2 1:00 p.m., 4:00 p.m., 5:30 p.m. CO and 7:00 p.m. -

Education for Research, Research for Creativity Edited by Jan Słyk and Lia Bezerra

EDUCATION FOR RESEARCH RESEACH FOR CREATIVITY Edited by Jan Słyk and Lia Bezerra EDUCATION FOR RESEARCH RESEACH FOR CREATIVITY Edited by Jan Słyk and Lia Bezerra Warsaw 2016 Architecture for the Society of Knowledge, volume 1 Education for Research, Research for Creativity Edited by Jan Słyk and Lia Bezerra Assistant editor: Karolina Ostrowska-Wawryniuk Scientific board: Stefan Wrona Jerzy Wojtowicz Joanna Giecewicz Graphic design: Gabriela Waśko VOSTOK DESIGN Printing: Argraf Sp. z.o.o ul. Jagiellońska 80, 03-301 Warszawa ISBN: 978-83-941642-2-5 ISSN: 2450-8918 Publisher: Wydział Architektury Politechniki Warszawskiej ul. Koszykowa 55, 00-659 Warszawa, Polska Copywright © by Wydział Architektury Politechniki Warszawskiej Warszawa 2016, Polska All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopy, recording, scanning, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. This book is part of a project supported by a grant from Norway through the Norway Grants and co-financed by the Polish funds. The publisher makes no representation, express or implied, with regard to the accuracy of the information contained in this book and cannot accept any legal responsibility or liability for any errors or omissions that may be made. The findings and conclusions of this book are solely representative of the authors’ beliefs. Opinions, findings and other writings published in this book in no way reflect the opinion or position of the publisher, scientific board, editor, its sponsors and other affiliated institutions. CONTENTS Foreword Jan Słyk and Lia Bezerra 7 EDUCATION Developing a New PhD Curriculum for an English-speaking Doctoral Course at the Architecture for the Society of Knowledge Program, Faculty of Architecture, Warsaw University of Technology Jan Słyk, Krzysztof Koszewski, Karolina Ostrowska, Lia M. -

Robert's Roughguide to Rajasthan

Robert’s Royal Rajasthan Rider’s Roughguide in association with All work herein has been sourced and collated by Robert Crick, a participant in the 2007 Ferris Wheels Royal Rajasthan Motorcycle Safari, from various resources freely available on the Internet. Neither the author nor Ferris Wheels make any assertions as to the relevance or accuracy of any content herein. 2 CONTENTS 1 HISTORY OF INDIA - AN OVERVIEW ....................................... 3 POLITICAL INTRODUCTION TO INDIA ..................................... 4 TRAVEL ADVISORY FOR INDIA ............................................... 6 ABOUT RAJASTHAN .............................................................. 9 NEEMRANA (ALWAR) ........................................................... 16 MAHANSAR ......................................................................... 16 BIKANER ............................................................................ 17 PHALODI ............................................................................ 21 JAISALMER ......................................................................... 23 JODPHUR ........................................................................... 26 PALI .................................................................................. 28 MT ABU .............................................................................. 28 UDAIPUR ............................................................................ 31 AJMER/PUSKAR ................................................................... 36 JAIPUR -

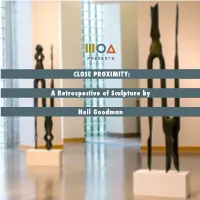

A Retrospective of Sculpture by CLOSE PROXIMITY: Neil Goodman

PRESENTS CLOSE PROXIMITY: A Retrospective of Sculpture by Neil Goodman Contents Introduction ............................. 10 Foreword ..................................19 Artist’s Statement ..................... 33 PRESENTS Interview ................................. 38 Neil Goodman Biography .......... 48 CLOSE PROXIMITY: Artwork Plates ......................... 50 A Retrospective of Sculpture by Founded in 1981 with the mission of “making art a part of everyday life”, the Museum of Outdoor Arts (MOA) is a forerunner in the placement of site-specific sculpture in Colorado. Our art collection is located at public locations throughout the Denver metro area. From commercial office parks to botanic gardens, city parks and traditional sculpture gardens; art is placed to interpret space as Neil Goodman “a museum without walls.” MOA also curates indoor galleries and hosts world-class art exhibitions and educational programs. Please visit our website to learn more about MOA. MOAonline.org MOA INDOOR GALLERY Follow Us @OutdoorArts 1000 Englewood Parkway, Second Floor, Englewood, CO 80110 Exhibiting September 15 – November 17, 2018 OUTDOOR INSTALLATION AT WESTLANDS PARK All photography by 5701 South Quebec Street, Greenwood Village, CO 80111 Heather Longway Exhibiting September 2018 – August 2019 2 CLOSE PROXIMITY: A Retrospective of Sculpture by Neil Goodman MOA, September 15 - November 17, 2018 3 4 CLOSE PROXIMITY: A Retrospective of Sculpture by Neil Goodman MOA, September 15 - November 17, 2018 5 6 CLOSE PROXIMITY: A Retrospective of Sculpture by Neil Goodman MOA, September 15 - November 17, 2018 7 8 CLOSE PROXIMITY: A Retrospective of Sculpture by Neil Goodman MOA, September 15 - November 17, 2018 9 INTRODUCTION retrospective exhibition. We all became fast the massive sculptures frame the landscape. friends and enthusiastic collaborators. -

Brad J Goldberg

BRAD J GOLDBERG 5706 GOLIAD AVENUE DALLAS, TX 75206 . W 214 821 9692 . [email protected] . WWW.BRADJGOLDBERG.COM CURRENT PROJECTS 2014- Moore Square, Raleigh, North Carolina 2013- Washington D.C. Metro Innovation Center Station 2011- Passage, Pueblo Grande Archeological Museum, Phoenix, Arizona 2009- Terminal 4 Terrazzo Floor Project, Ft. Lauderdale International Airport, Florida COMPLETED PROJECTS 2014 Trinity River Amenities Project, Dallas, Texas 2012 Water Tower, Elevated Water Tower Design/Wind Energy Project, Town of Addison, Texas 2012 Belt Line Station, Dallas Area Rapid Transit, Irving, Texas 2011 Every Place A History, Austin Animal Shelter/Betty Dunkerley Campus, Austin, Texas 2011 Water Table, Cityplace, Dallas, Texas 2011 Bollard Series, West Palm Beach County Courthouse Project, West Palm Beach, Florida 2011 Alluvium, Pinnacle/Pima Road Project, Scottsdale, Arizona 2010 Healing Stones, Solar Light Project, Children’s Hospital, Minneapolis, Minnesota 2010 DART System-Wide Lead Artist, Dallas Area Rapid Transit Projects (12 Years) 2009 Trinity Lakes Project, Conceptual Design, Design Team Member with WRT, Dallas, Texas 2009 Fair Park Station, Dallas Area Rapid Transit, Main Entrance to Fair Park, Dallas, Texas 2007 Cisterna, Stone Cistern and Wind Turbine Project, Montgomery Farm, Allen, Texas 2007 Illumination, Symantec Corporation Solar Light Project, Culver City, California 2007 Coral Eden, Miami International Airport Project, Miami, Florida 2006 Place of Origin, Land Reclamation Project, Village of Kemnay, Aberdeenshire,