Ruled with a Pen: Land, Language, and the Invention of Maine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Boundaries of Nationality in Mid-18Th Century Nova Scotia*

GEOFFREY PLANK The Two Majors Cope: The Boundaries of Nationality in Mid-18th Century Nova Scotia* THE 1750S BEGAN OMINOUSLY IN Nova Scotia. In the spring of 1750 a company of French soldiers constructed a fort in a disputed border region on the northern side of the isthmus of Chignecto. The British built a semi-permanent camp only a few hundred yards away. The two armies faced each other nervously, close enough to smell each other's food. In 1754 a similar situation near the Ohio River led to an imperial war. But the empires were not yet ready for war in 1750, and the stand-off at Chignecto lasted five years. i In the early months of the crisis an incident occurred which illustrates many of *' the problems I want to discuss in this essay. On an autumn day in 1750, someone (the identity of this person remains in dispute) approached the British fort waving a white flag. The person wore a powdered wig and the uniform of a French officer. He carried a sword in a sheath by his side. Captain Edward Howe, the commander of the British garrison, responded to the white flag as an invitation to negotiations and went out to greet the man. Then someone, either the man with the flag or a person behind him, shot and killed Captain Howe. According to three near-contemporary accounts of these events, the man in the officer's uniform was not a Frenchman but a Micmac warrior in disguise. He put on the powdered wig and uniform in order to lure Howe out of his fort. -

General Index

General Index Italicized page numbers indicate figures and tables. Color plates are in- cussed; full listings of authors’ works as cited in this volume may be dicated as “pl.” Color plates 1– 40 are in part 1 and plates 41–80 are found in the bibliographical index. in part 2. Authors are listed only when their ideas or works are dis- Aa, Pieter van der (1659–1733), 1338 of military cartography, 971 934 –39; Genoa, 864 –65; Low Coun- Aa River, pl.61, 1523 of nautical charts, 1069, 1424 tries, 1257 Aachen, 1241 printing’s impact on, 607–8 of Dutch hamlets, 1264 Abate, Agostino, 857–58, 864 –65 role of sources in, 66 –67 ecclesiastical subdivisions in, 1090, 1091 Abbeys. See also Cartularies; Monasteries of Russian maps, 1873 of forests, 50 maps: property, 50–51; water system, 43 standards of, 7 German maps in context of, 1224, 1225 plans: juridical uses of, pl.61, 1523–24, studies of, 505–8, 1258 n.53 map consciousness in, 636, 661–62 1525; Wildmore Fen (in psalter), 43– 44 of surveys, 505–8, 708, 1435–36 maps in: cadastral (See Cadastral maps); Abbreviations, 1897, 1899 of town models, 489 central Italy, 909–15; characteristics of, Abreu, Lisuarte de, 1019 Acequia Imperial de Aragón, 507 874 –75, 880 –82; coloring of, 1499, Abruzzi River, 547, 570 Acerra, 951 1588; East-Central Europe, 1806, 1808; Absolutism, 831, 833, 835–36 Ackerman, James S., 427 n.2 England, 50 –51, 1595, 1599, 1603, See also Sovereigns and monarchs Aconcio, Jacopo (d. 1566), 1611 1615, 1629, 1720; France, 1497–1500, Abstraction Acosta, José de (1539–1600), 1235 1501; humanism linked to, 909–10; in- in bird’s-eye views, 688 Acquaviva, Andrea Matteo (d. -

Hclassification

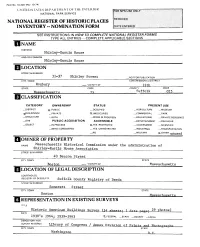

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THh INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC ShirleyrEustis Rouse AND/OR COMMON Shirley'-Eustis House LOCATION STREETS NUMBER 31^37 Shirley Street -NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Roxbury _ VICINITY OF 12th STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 9^ Suffolk 025 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT ^PUBLIC —OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM -^BUILDING(S) _PRIVATE X-UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS X-YES. RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED _YES. UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY x-OTHER unused OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Massachusetts Historical Commission under the administration of ShirleyrEustis Eouse Association_________________________ STREETS NUMBER 4Q Beacon Street CITY. TOWN STATE Boston VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS. ETC Suffolk County Registry of Deeds STREETS NUMBER Somerset Street CITY. TOWN STATE Boston Mas s achtis e t t s REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey (14 sheets. 1 29 photos) DATE 1930 f-s 1964. 1939^1963 FEDERAL _STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress / Annex Division of Prints and CITY. TOWN STATE Washington n.r DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE .EXCELLENT ^DETERIORATED —UNALTERED __ORIGINALSITE _GOOD _RUINS ^ALTERED DATE. -FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The house, constructed from 1741 to 1756 for Governor William Shirley of Massachusetts became somewhat of a colonial showplace with its imposing facades and elaborate interior designs. -

John Clarence Webster Fonds

The Osler Library of the History of Medicine McGill University, Montreal Canada Osler Library Archive Collections P11 JOHN CLARENCE WEBSTER FONDS PARTIAL INVENTORY LIST This is a guide to one of the collections held by the Osler Library of the History of Medicine, McGill University. Visit the Osler Library Archive Collections homepage for more information P11: JOHN CLARENCE WEBSTER FONDS TITLE: John Clarence Webster fonds DATES: 1892-1952. EXTENT: 13,8 cm of textual records. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH: John Clarence Webster was born 21 October 1863 in Shediac, New Brunswick, which was also where he did his primary studies. He graduated from Mount Allison College in Sackville, New Brunswick in 1882 with a Bachelor of Arts degree. In 1883, he began his medical studies at the University of Edinburgh where he graduated with a Bachelor of Medicine and a Masters in Surgery in 1888. During the course of his medical training he went to Leipzig and Berlin. He worked as an assistant in the Department of Midwifery and Diseases of Women at the University of Edinburgh until his return to Canada in 1896. He settled in Montreal and was appointed Lecturer in Gynecology at McGill University and Assistant Gynecologist to the Royal Victoria Hospital. In 1899, he accepted an offer to fill the Chair of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Rush Medical College, affiliated with the University of Chicago. He also worked in Hospital at the Presbyterian Hospital, the Central Free Dispensary, and at the St Anthony’s and St Joseph’s Hospitals in Chicago. He retired in 1920. During his career he won prizes, and received many scholarships and honours. -

Education, Instruction and Apprenticeship at the London Foundling Hospital C.1741 - 1800

Fashioning the Foundlings – Education, Instruction and Apprenticeship at the London Foundling Hospital c.1741 - 1800 Janette Bright MRes in Historical Research University of London September 2017 Institute of Historical Research School of Advanced Study Index Chapter One – Introduction Pages 2 - 14 Chapter Two – Aims and objectives Pages 14 - 23 Chapter Three - Educating the Foundlings: Pages 24 - 55 schooling and vocational instruction Chapter Four – Apprenticeship Pages 56 - 78 Chapter Five – Effectiveness and experience: Pages 79 - 97 assessing the outcomes of education and apprenticeship Chapter Six – Final conclusions Pages 98 - 103 Appendix – Prayers for the use of the foundlings Pages 104 - 105 Bibliography Pages 106 - 112 3 Chapter one: introduction Chapter One: Introduction Despite the prominence of the word 'education' in the official title of the London Foundling Hospital, that is 'The Hospital for the Maintenance and Education of Exposed and Deserted Young Children', it is surprising to discover this is an under researched aspect of its history. Whilst researchers have written about this topic in a general sense, gaps and deficiencies in the literature still exist. By focusing on this single component of the Hospital’s objectives, and combining primary sources in new ways, this study aims to address these shortcomings. In doing so, the thesis provides a detailed assessment of, first, the purpose and form of educational practice at the Hospital and, second, the outcomes of education as witnessed in the apprenticeship programme in which older foundlings participated. In both cases, consideration is given to key shifts in education and apprenticeship practices, and to the institutional and contextual forces that prompted these developments over the course of the eighteenth century. -

Folklore and Etymological Glossary of the Variants from Standard French in Jefferson Davis Parish

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1934 Folklore and Etymological Glossary of the Variants From Standard French in Jefferson Davis Parish. Anna Theresa Daigle Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Daigle, Anna Theresa, "Folklore and Etymological Glossary of the Variants From Standard French in Jefferson Davis Parish." (1934). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 8182. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/8182 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FOLKLORE AND ETYMOLOGICAL GLOSSARY OF THE VARIANTS FROM STANDARD FRENCH XK JEFFERSON DAVIS PARISH A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF SHE LOUISIANA STATS UNIVERSITY AND AGRICULTURAL AND MECHANICAL COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULLFILLMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE DEPARTMENT OF ROMANCE LANGUAGES BY ANNA THERESA DAIGLE LAFAYETTE LOUISIANA AUGUST, 1984 UMI Number: EP69917 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI Dissertation Publishing UMI EP69917 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). -

2019 Coram Accounts Designed FINAL Lowres.Pdf

Contents Reports Reference and administrative details 3 Chairman’s Report 5 Trustees’ Report 8 Independent Auditor’s Report 31 Accounts Consolidated statement of financial activities 34 Charity statement of financial activities 36 Balance sheets 38 Consolidated statement of cash flows 39 Prinicipal accounting policies 40 Notes to the accounts 45 Appendix Comparative statement of financial activities 78 Comparative notes to the financial statements 82 Last year... 10% 25,882 of adoptions in England Teachers subscribed were made possible by to SCARF Coram services 138,505 2,004 Children and parents helped Schools reached through Coram Life Education 427,621 4,016 Children supported by Coram’s Volunteers education and early years services 7,405 2,897,729 Professionals trained or Digital users of Coram’s advised specialist advice services 1 2 Reports Reference and administrative details The Thomas Coram Foundation for Children (Coram) President and Chairman Sir David Bell General Committee (Charity Trustees) Paul Curran – Vice Chairman Ade Adetosoye Robert Aitken Geoff Berridge - Honorary Treasurer Yogesh Chauhan Jenny Coles Judge Celia Dawson Tony Gamble William Gore Kim Johnson Dr Pui-Ling Li Jill Pay Jonathan Portes Dr Judith Trowell Chief Executive (CEO) Dr Carol Homden CBE Director of Operations Renuka Jeyarajah-Dent Chief Finance Officer Velou Singara Managing Director of Human Resources Christine Kelly Principal office Coram Community Campus, 41 Brunswick Square, London, WC1N 1AZ Telephone 020 7520 0300 Facsmile 020 7520 0301 Website -

A History of the Spiritan Missionaries in Acadia and North America 1732-1839 Henry J

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Duquesne Studies Spiritan Series Spiritan Collection 1-1-1962 Knaves or Knights? A History of the Spiritan Missionaries in Acadia and North America 1732-1839 Henry J. Koren C.S.Sp. Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/spiritan-dsss Recommended Citation Koren, H. J. (1962). Knaves or Knights? A History of the Spiritan Missionaries in Acadia and North America 1732-1839. Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/spiritan-dsss/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Spiritan Collection at Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Duquesne Studies Spiritan Series by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. Spiritan Collection Duquesne University The Gumberg Library Congregation of the Holy Spirit USA Eastern Province SPtRITAN ARCHIVES U.S.A. g_ / / Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/duquesnestudiess04henr DUQUESNE STUDIES Spiritan Series 4 KNAVES OR KNIGHTS? : DUQUESNE STUDIES Spiritan Series Volume One— Henry J. Koren. C S.Sp., THE SPIRI- TAN S. A History of the Congregation of the Holy Ghost. XXIX and 641 pages. Illustrated. Price: paper $5.75, cloth $6.50. ,,lt is a pleasure to meet profound scholarship and interesting writing united. " The American Ecclesias- tical Review. Volume Two— Adrian L. van Kaam, C.S.Sp., A LIGHT TO THE GENTILES. The Life-Story of the Venerable Francis Lihermann. XI and 312 pages. Illustrated Price: paper $4.00, cloth $4.75. ,,A splendid example or contemporary hagiography at its best." America. -

Finding Aid to the Alexander Wadsworth Longfellow

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Finding Aid Alexander Wadsworth Longfellow Jr. (1854-1934) Papers, 1864-1979 (Bulk dates: 1872-1934) Catalog No. LONG 35725; Individual Numbers: LONG 5157, 33379-33380 Longfellow National Historic Site Cambridge, Massachusetts 1. LONGFELLOW NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE 105 BRATTLE STREET CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS FINDING AID FOR THE ALEXANDER WADSWORTH LONGFELLOW JR. (1854-1934) PAPERS, 1864-1979 BULK DATES ( : 1872-1934) COLLECTION: LONG 35725 INDIVIDUAL CATALOG NUMBERS: LONG 5175, 33379-33380 Accessions: LONG-1 PREPARED BY MARGARET WELCH Northeast Museum Services Center FALL 2005 REVISED FALL 2006 Cover Illustration: Alexander Wadsworth Longfellow (1854-1934), by the photographer Marceau, ca. 1920. He is holding an American Architect Magazine. 3007-3-2-4-59, Longfellow Family Photograph Collection, Box 35, Env. 12. Illustration Above: Alexander Wadsworth Longfellow (1854-1934), February 1876. This is one of the Harvard senior photographs taken by William Notman. 3007-3-2- 4-1, Longfellow Family Photograph Collection, Box 34, Env. 32. Images courtesy of the Longfellow National Historic Site. CONTENTS Preface.............................................................................................................................................. i Restrictions .................................................................................................................................... iii Introduction......................................................................................................................................1 -

Penhallow's Indian Wars Seems to Have Been Predestined to Become a Scarce Book

PENH ALLOWS INDIAN WARS A Facsimile Reprint of the First Edition, Printed in Boston in 1726 With the Notes of Earlier Editors and Additions from the Original Manuscript Notes, Index and Introduction by EDWARD WHEELOCK BOSTON 1924 no."/ The edition of this reprint is limited to 250 copies Introduction Penhallow's History of the Indian Wars is one of the rarest books of its class. When it first appeared it doubtless was read by some who may have been able to recall the setting up of the first printing press in New England; to most of its early readers the impressions of that first press were familiar objects. Though we may thus associate the book with the earliest of New England imprints, its age alone does not account for the scarcity of surviving copies, for many older books are more common. Its disappearance seems better explained by the fact that matters concerning the Indians were, excepting possibly religious controversies, of the greatest interest to the readers of that time and that such books as these were literally read to pieces; they were issued moreover in only small editions for relatively few readers, as there were probably not 175,000 people in the New England Colonies in 1726. Here, moreover, the facilities for the preserva- tion of printed matter were in general poor; too often in the outlying settlements the leaky cup- board was the library and the hearth with its flickering pine knot was the study. At the writer's elbow lies a copy of Penhallow's rare History, the mutilated survivor of a fireplace ii INTRODUCTION. -

This Week in New Brunswick History

This Week in New Brunswick History In Fredericton, Lieutenant-Governor Sir Howard Douglas officially opens Kings January 1, 1829 College (University of New Brunswick), and the Old Arts building (Sir Howard Douglas Hall) – Canada’s oldest university building. The first Baptist seminary in New Brunswick is opened on York Street in January 1, 1836 Fredericton, with the Rev. Frederick W. Miles appointed Principal. Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) becomes responsible for all lines formerly January 1, 1912 operated by the Dominion Atlantic Railway (DAR) - according to a 999 year lease arrangement. January 1, 1952 The town of Dieppe is incorporated. January 1, 1958 The city of Campbellton and town of Shippagan become incorporated January 1, 1966 The city of Bathurst and town of Tracadie become incorporated. Louis B. Mayer, one of the founders of MGM Studios (Hollywood, California), January 2, 1904 leaves his family home in Saint John, destined for Boston (Massachusetts). New Brunswick is officially divided into eight counties of Saint John, Westmorland, Charlotte, Northumberland, King’s, Queen’s, York and Sunbury. January 3, 1786 Within each county a Shire Town is designated, and civil parishes are also established. The first meeting of the New Brunswick Legislature is held at the Mallard House January 3, 1786 on King Street in Saint John. The historic opening marks the official business of developing the new province of New Brunswick. Lévite Thériault is elected to the House of Assembly representing Victoria January 3, 1868 County. In 1871 he is appointed a Minister without Portfolio in the administration of the Honourable George L. Hatheway. -

Wabanaki Textiles, Clothing, and Costume. Bruce J. Bourque and Laureen A

Uncommon Threads: Wabanaki Textiles, Clothing, and Costume. Bruce J. Bourque and Laureen A. LaBar. Augusta, ME: Maine State Museum with the University of Washington Press, 2009. 192 pp.* Reviewed by Rhonda S. Fair In May of 2009, the Maine State Museum launched an exhibit of 100 Wabanaki objects; Bruce Bourque and Laureen LaBar curated the exhibit and wrote the companion book, Uncommon Threads: Wabanaki Textiles, Clothing, and Costume. Much more than a catalog of the objects on display, this book provides an examination of the history, art, and culture of the Maritime Peninsula’s indigenous population. After a very brief introduction, Bourque and LaBar divide their subject matter into four chapters, the first of which provides an overview of the Native peoples of the Maritime Peninsula. Though related to other Algonquian-speaking tribes along the eastern seaboard, the Wabanaki differed in some significant ways. For instance, the Wabanaki groups did not practice agriculture based on corn, beans, and squash, preferring instead to hunt and gather a significant portion of their diet. As did other Native peoples on the coast, they had early contact with Europeans, first with fishermen and fur traders, and later, with colonists and soldiers. Also like their neighbors, the Iroquois, the Wabanki formed a coalition of affiliated tribal groups. Frank Speck described this as the Wabanaki Confederacy. He observed that the Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, Maliseet, and Micmac had an identifiable national identity and met in common to discuss matters that would impact the confederacy as a whole. Agreements by the confederacy were documented not by written words, but with woven shell beads, or wampum.