Aftermath of the 1983 Beirut Bombing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jazzweek Jazz Album Chart Sept

airplay data JazzWeek Jazz Album Chart Sept. 11, 2006 powered by TW LW 2W Peak Artist Release Label TP LP +/- Weeks Stations Adds 1 1 1 1 Dr. Lonnie Smith Jungle Soul Palmetto 367 398 -31 7 73 0 2 5 NR 2 Cedar Walton One Flight Down HighNote 251 191 60 2 54 14 3 4 4 3 Frank Morgan Reflections HighNote 230 193 37 7 58 2 4 2 2 1 Regina Carter I’ll Be Seeing You (A Sentimental Journey) Verve Music Group 228 245 -17 11 61 0 5 3 3 3 Jon Faddis Teranga Koch 226 200 26 11 50 4 6 20 30 6 Winard Harper Make It Happen Piadrum 208 156 52 4 53 2 7 6 5 5 Brad Mehldau Trio House On Hill Nonesuch 189 190 -1 8 43 1 7 NR NR 7 Houston Person & Bill Charlap You Taught My Heart To Sing HighNote 189 77 112 1 50 17 9 7 14 7 Anton Schwartz Radiant Blue Anton Jazz 185 185 0 3 48 3 10 27 8 8 Buck Hill Relax Severn 181 139 42 6 47 1 11 8 16 8 Freddy Cole Because Of You HighNote 179 175 4 7 56 1 12 9 21 9 Scott Hamilton Nocturnes and Serenades Concord Jazz 178 174 4 5 49 3 12 18 18 12 The Chris Walden Big Band No Bounds Origin 178 158 20 7 42 1 12 15 13 12 Ray Barretto Standards Rican-ditioned Zoho Music 178 167 11 4 51 3 15 28 26 15 Joe Lovano Streams of Expression Blue Note 166 136 30 4 44 3 15 16 9 6 Hank Jones & Frank Wess Hank & Frank Lineage Records 166 164 2 13 37 0 17 9 6 5 Gordon Goodwin’s Big Phat Band The Phat Pack Immergent 165 174 -9 6 38 2 18 29 14 5 Eric Reed Here MAXJAZZ 163 134 29 14 46 1 19 13 6 1 Roy Hargrove Nothing Serious Verve Music Group 161 172 -11 19 56 1 20 33 39 20 Ann Hampton Calloway Blues In The Night Telarc 160 125 35 3 43 6 21 25 -

Star Channels, May 20-26

MAY 20 - 26, 2018 staradvertiser.com LEGAL EAGLES Sandra’s (Britt Robertson) confi dence is shaken when she defends a scientist accused of spying for the Chinese government in the season fi nale of For the People. Elsewhere, Adams (Jasmin Savoy Brown) receives a compelling offer. Chief Judge Nicholas Byrne (Vondie Curtis-Hall) presides over the Southern District of New York Federal Court in this legal drama, which wraps up a successful freshman season. Airing Tuesday, May 22, on ABC. WE’RE LOOKING FOR PEOPLE WHO HAVE SOMETHING TO SAY. Are you passionate about an issue? An event? A cause? ¶ũe^eh\Zga^eirhn[^a^Zk][r^fihp^kbg`rhnpbmama^mkZbgbg`%^jnbif^gm olelo.org Zg]Zbkmbf^rhng^^]mh`^mlmZkm^]'Begin now at olelo.org. ON THE COVER | FOR THE PEOPLE Case closed ABC’s ‘For the People’ wraps Deavere Smith (“The West Wing”) rounds example of how the show delves into both the out the cast as no-nonsense court clerk Tina professional and personal lives of the charac- rookie season Krissman. ters. It’s a formula familiar to fans of Shonda The cast of the ensemble drama is now part Rhimes, who’s an executive producer of “For By Kyla Brewer of the Shondaland dynasty, which includes hits the People,” along with Davies, Betsy Beers TV Media “Grey’s Anatomy,” “Scandal” and “How to Get (“Grey’s Anatomy”), Donald Todd (“This Is Us”) Away With Murder.” The distinction was not and Tom Verica (“How to Get Away With here’s something about courtroom lost on Rappaport, who spoke with Murder”). -

Introduction Chapter 1

Notes Introduction 1. Thomas S. Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, 2nd ed. (Chicago: Univer- sity of Chicago Press, 1970). 2. Ralph Pettman, Human Behavior and World Politics: An Introduction to International Relations (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1975); Giandomenico Majone, Evidence, Argument, and Persuasion in the Policy Process (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1989), 275– 76. 3. Bernard Lewis, “The Return of Islam,” Commentary, January 1976; Ofira Seliktar, The Politics of Intelligence and American Wars with Iraq (New York: Palgrave Mac- millan, 2008), 4. 4. Martin Kramer, Ivory Towers on Sand: The Failure of Middle Eastern Studies in Amer- ica (Washington, DC: Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 2000). 5. Bernard Lewis, “The Roots of Muslim Rage,” Atlantic Monthly, September, 1990; Samuel P. Huntington, “The Clash of Civilizations,” Foreign Affairs 72 (1993): 24– 49; Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of the World Order (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996). Chapter 1 1. Quoted in Joshua Muravchik, The Uncertain Crusade: Jimmy Carter and the Dilemma of Human Rights (Lanham, MD: Hamilton Press, 1986), 11– 12, 114– 15, 133, 138– 39; Hedley Donovan, Roosevelt to Reagan: A Reporter’s Encounter with Nine Presidents (New York: Harper & Row, 1985), 165. 2. Charles D. Ameringer, U.S. Foreign Intelligence: The Secret Side of American History (Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1990), 357; Peter Meyer, James Earl Carter: The Man and the Myth (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1978), 18; Michael A. Turner, “Issues in Evaluating U.S. Intelligence,” International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence 5 (1991): 275– 86. 3. Abram Shulsky, Silent Warfare: Understanding the World’s Intelligence (Washington, DC: Brassey’s [US], 1993), 169; Robert M. -

Kappale Artisti

14.7.2020 Suomen suosituin karaokepalvelu ammattikäyttöön Kappale Artisti #1 Nelly #1 Crush Garbage #NAME Ednita Nazario #Selˆe The Chainsmokers #thatPOWER Will.i.am Feat Justin Bieber #thatPOWER Will.i.am Feat. Justin Bieber (Baby I've Got You) On My Mind Powderˆnger (Barry) Islands In The Stream Comic Relief (Call Me) Number One The Tremeloes (Can't Start) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue (Doo Wop) That Thing Lauren Hill (Every Time I Turn Around) Back In Love Again LTD (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Brandy (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Bryan Adams (Hey Won't You Play) Another Somebody Done Somebody Wrong Song B. J. Thomas (How Does It Feel To Be) On Top Of The W England United (I Am Not A) Robot Marina & The Diamonds (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction The Rolling Stones (I Could Only) Whisper Your Name Harry Connick, Jr (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew (If Paradise Is) Half As Nice Amen Corner (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Shania Twain (I'll Never Be) Maria Magdalena Sandra (It Looks Like) I'll Never Fall In Love Again Tom Jones (I've Had) The Time Of My Life Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes (I've Had) The Time Of My Life Bill Medley-Jennifer Warnes (I've Had) The Time Of My Life (Duet) Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes (Just Like) Romeo And Juliet The Re˜ections (Just Like) Starting Over John Lennon (Marie's The Name) Of His Latest Flame Elvis Presley (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Elvis Presley (Reach Up For The) Sunrise Duran Duran (Shake, Shake, Shake) Shake Your Booty KC And The Sunshine Band (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay Otis Redding (Theme From) New York, New York Frank Sinatra (They Long To Be) Close To You Carpenters (We're Gonna) Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & His Comets (Where Do I Begin) Love Story Andy Williams (You Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears (You Gotta) Fight For Your Right (To Party!) The Beastie Boys 1+1 (One Plus One) Beyonce 1000 Coeurs Debout Star Academie 2009 1000 Miles H.E.A.T. -

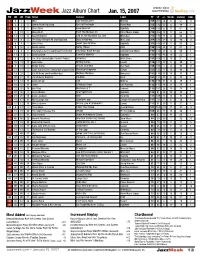

Jazzweek Jazz Album Chart Jan

airplay data JazzWeek Jazz Album Chart Jan. 15, 2007 powered by TW LW 2W Peak Artist Release Label TP LP +/- Weeks Stations Adds 1 2 7 1 MB3 Jazz Hits Volume 1 Mel Bay 259 201 58 8 57 0 2 3 2 2 Jimmy Heath Big Band Turn Up The Heath Planet Arts 255 192 63 8 49 1 3 3 3 1 Steve Turre Keep Searchin’ HighNote 254 192 62 11 61 2 4 1 10 1 Diana Krall From This Moment On Verve Music Group 218 205 13 17 55 0 5 13 13 5 Russell Malone Live at Jazz Standard, Vol. One MAXJAZZ 212 135 77 8 56 3 6 10 9 2 The Dizzy Gillespie All-Star Big Band Dizzy’s Business MCG Jazz 204 150 54 15 49 0 7 6 4 1 John Hicks Sweet Love Of Mine HighNote 203 156 47 11 55 2 8 9 16 4 Sonny Rollins Sonny, Please Doxy 198 152 46 11 57 1 9 11 8 3 Ray Charles & The Count Basie Orchestra Ray Sings, Basie Swings Concord/Hear Music 193 146 47 14 59 1 10 11 6 6 Dave Valentin Come Fly With Me HighNote 192 146 46 10 53 1 11 5 12 5 The Brian Lynch/Eddie Palmieri Project Simpatico Artist Share 181 169 12 15 51 2 12 15 19 12 Bob DeVos Shifting Sands Savant 178 131 47 6 48 3 13 7 10 2 Stefon Harris African Tarantella Blue Note 159 155 4 14 45 0 14 13 13 2 Louis Hayes & The Cannonball Legacy Band Maximum Firepower Savant 152 135 17 15 40 1 15 19 20 2 Pat Metheny and Brad Mehldau Metheny Mehldau Nonesuch 151 116 35 16 43 1 15 20 17 15 The Brubeck Brothers Intutition Koch 151 114 37 6 46 1 17 17 22 17 Lynne Arriale Live Motema 146 119 27 12 39 1 18 18 23 14 Tomo I’ll Always Know Torii Records 135 117 18 11 34 1 19 22 28 16 Ben Riley Memories of T Concord 133 105 28 10 34 1 20 23 26 2 Cedar -

Æ‚‰É”·ȯLj¾é “ Éÿ³æ¨‚Å°ˆè¼¯ ĸ²È¡Œ (ĸ“Ⱦ

æ‚‰é” Â·è¯ çˆ¾é “ 音樂專輯 串行 (专辑 & æ—¶é— ´è¡¨) Spectrum https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/spectrum-7575264/songs The Electric Boogaloo Song https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-electric-boogaloo-song-7731707/songs Soundscapes https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/soundscapes-19896095/songs Breakthrough! https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/breakthrough%21-4959667/songs Beyond Mobius https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/beyond-mobius-19873379/songs The Pentagon https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-pentagon-17061976/songs Composer https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/composer-19879540/songs Roots https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/roots-19895558/songs Cedar! https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/cedar%21-5056554/songs The Bouncer https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-bouncer-19873760/songs Animation https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/animation-19872363/songs Duo https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/duo-30603418/songs The Maestro https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-maestro-19894142/songs Voices Deep Within https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/voices-deep-within-19898170/songs Midnight Waltz https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/midnight-waltz-19894330/songs One Flight Down https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/one-flight-down-20813825/songs Manhattan Afternoon https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/manhattan-afternoon-19894199/songs Soul Cycle https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/soul-cycle-7564199/songs -

Prestige Label Discography

Discography of the Prestige Labels Robert S. Weinstock started the New Jazz label in 1949 in New York City. The Prestige label was started shortly afterwards. Originaly the labels were located at 446 West 50th Street, in 1950 the company was moved to 782 Eighth Avenue. Prestige made a couple more moves in New York City but by 1958 it was located at its more familiar address of 203 South Washington Avenue in Bergenfield, New Jersey. Prestige recorded jazz, folk and rhythm and blues. The New Jazz label issued jazz and was used for a few 10 inch album releases in 1954 and then again for as series of 12 inch albums starting in 1958 and continuing until 1964. The artists on New Jazz were interchangeable with those on the Prestige label and after 1964 the New Jazz label name was dropped. Early on, Weinstock used various New York City recording studios including Nola and Beltone, but he soon started using the Rudy van Gelder studio in Hackensack New Jersey almost exclusively. Rudy van Gelder moved his studio to Englewood Cliffs New Jersey in 1959, which was close to the Prestige office in Bergenfield. Producers for the label, in addition to Weinstock, were Chris Albertson, Ozzie Cadena, Esmond Edwards, Ira Gitler, Cal Lampley Bob Porter and Don Schlitten. Rudy van Gelder engineered most of the Prestige recordings of the 1950’s and 60’s. The line-up of jazz artists on Prestige was impressive, including Gene Ammons, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Eric Dolphy, Booker Ervin, Art Farmer, Red Garland, Wardell Gray, Richard “Groove” Holmes, Milt Jackson and the Modern Jazz Quartet, “Brother” Jack McDuff, Jackie McLean, Thelonious Monk, Don Patterson, Sonny Rollins, Shirley Scott, Sonny Stitt and Mal Waldron. -

Who Needs the Conference of Presidents?

MAY 1993 PUBLISHED BY AMERICANS FOR A SAFE ISRAEL Conference is even more fraught with danger because its WHO NEEDS THE positions are more extreme than those of the AJC. Peace Now calls for talks with the PLO, endorses Palestinian CONFERENCE OF statehood, and refuses to support Israeli sovereignty over PRESIDENTS? all of Jerusalem. Its president, Gail Pressberg, spent 14 years working for two pro-PLO organizations, and its co- Herbert Zweibon chair, Letty Pogrebin, has justified Arab rock-throwing. Numerous Peace Now board members also served in Shortly before the recent vote on whether or not leadership positions of radical groups like the Jewish to admit Americans for Peace Now to the Conference of Peace Lobby and the New Jewish Agenda. From now on, Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations, the Conference of Presidents will not able to issue any Rabbi Joseph Glaser, chairman of the Conference's resolution that does not suit Peace Now's extremist tastes. Committee on Scope and Structure, publicly warned that Whether the Conference of Presidents ever really the admission of Peace Now, with its narrow political represented American Jewry is debatable, since the lead- agenda and ruthless tactics, would "hobble and under- ers of its member-organizations are not democratically cut the purposes for which the Conference was estab- elected. The fact that Peace Now was admitted in contra- lished." Rabbi Glaser subsequently resigned from that vention of several of the Conference's own by-laws (which committee in protest over irregularities in the conduct of is what prompted Rabbi Glaser's resignation) is further the Peace Now admissions process, Peace Now was testimony to the absence of democracy and fair play admitted and it seems that the Conference of Presidents among the Conference's top brass. -

Pianodisc Music Catalog.Pdf

Welcome Welcome to the latest edition of PianoDisc's Music Catalog. Inside you’ll find thousands of songs in every genre of music. Not only is PianoDisc the leading manufacturer of piano player sys- tems, but our collection of music software is unrivaled in the indus- try. The highlight of our library is the Artist Series, an outstanding collection of music performed by the some of the world's finest pianists. You’ll find recordings by Peter Nero, Floyd Cramer, Steve Allen and dozens of Grammy and Emmy winners, Billboard Top Ten artists and the winners of major international piano competi- tions. Since we're constantly adding new music to our library, the most up-to-date listing of available music is on our website, on the Emusic pages, at www.PianoDisc.com. There you can see each indi- vidual disc with complete song listings and artist biographies (when applicable) and also purchase discs online. You can also order by calling 800-566-DISC. For those who are new to PianoDisc, below is a brief explana- tion of the terms you will find in the catalog: PD/CD/OP: There are three PianoDisc software formats: PD represents the 3.5" floppy disk format; CD represents PianoDisc's specially-formatted CDs; OP represents data disks for the Opus system only. MusiConnect: A Windows software utility that allows Opus7 downloadable music to be burned to CD via iTunes. Acoustic: These are piano-only recordings. Live/Orchestrated: These CD recordings feature live accom- paniment by everything from vocals or a single instrument to a full-symphony orchestra. -

Theater Playbills and Programs Collection, 1875-1972

Guide to the Brooklyn Theater Playbills and Programs Collection, 1875-1972 Brooklyn Public Library Grand Army Plaza Brooklyn, NY 11238 Contact: Brooklyn Collection Phone: 718.230.2762 Fax: 718.857.2245 Email: [email protected] www.brooklynpubliclibrary.org Processed by Lisa DeBoer, Lisa Castrogiovanni and Lisa Studier. Finding aid created in 2006. Revised and expanded in 2008. Copyright © 2006-2008 Brooklyn Public Library. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Creator: Various Title: Brooklyn Theater Playbills and Programs Collection Date Span: 1875-1972 Abstract: The Brooklyn Theater Playbills and Programs Collection consists of 800 playbills and programs for motion pictures, musical concerts, high school commencement exercises, lectures, photoplays, vaudeville, and burlesque, as well as the more traditional offerings such as plays and operas, all from Brooklyn theaters. Quantity: 2.25 linear feet Location: Brooklyn Collection Map Room, cabinet 11 Repository: Brooklyn Public Library – Brooklyn Collection Reference Code: BC0071 Scope and Content Note The 800 items in the Brooklyn Theater Playbills and Programs Collection, which occupies 2.25 cubic feet, easily refute the stereotypes of Brooklyn as provincial and insular. From the late 1880s until the 1940s, the period covered by the bulk of these materials, the performing arts thrived in Brooklyn and were available to residents right at their doorsteps. At one point, there were over 200 theaters in Brooklyn. Frequented by the rich, the middle class and the working poor, they enjoyed mass popularity. With materials from 115 different theaters, the collection spans almost a century, from 1875 to 1972. The highest concentration is in the years 1890 to 1909, with approximately 450 items. -

Download Your Copy of the Equinox Press Pack Here

www.equinoxjazzquintet.com The band Equinox is a collective of five like minded musicians who share the desire to celebrate a common sense of balance; that between tension and resolution, between dissonance and consonance, between the present and the past. Based in the Netherlands, Equinox is co-lead by Guitarist Dan Nicholas and bassist Johnny Daly. Nicholas comes from New York City and Daly is a native of Dublin, Ireland. Both musicians have made the Netherlands their home, inspired by the rich jazz climate they found there. Joining Nicholas and Daly in Equinox are three of the country’s top jazz musicians; the soulful and powerful tenor saxophonist Sjoerd Dijkhuizen, the elegant and adventurous pianist Bob Wijnen and master drummer Marcel Serierse. The band plays a mix of vivid original pieces, personal arrangements of standards and classic jazz repertoire by the likes of Thelonious Monk, Billy Strayhorn, Charles Mingus and Horace Silver. Equinox is deeply rooted in a wide spectrum of jazz tradition, which constantly informs the band’s musical explorations. The individual members of the band all draw inspiration from this tradition in the development of their own personal avenues of musical expression. “...Great playing and strong writing... They have forged their own musical identities while addressing the roots of the music. This is a great band that we will be hearing many great things from in the future.” Guitarist Peter Bernstein www.equinoxjazzquintet.com Guitarist Dan Nicholas grew up in New York City and New Jersey. At the age of 18 he began to study Bassist Johnny Daly is a native of with the world renowned jazz Dublin Ireland, where he paid his pianist and educator, Dr. -

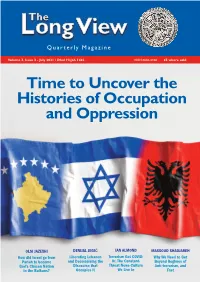

Time to Uncover the Histories of Occupation and Oppression

Quarterly Magazine Volume 3, Issue 3 - July 2021 / Dhul Hijjah 1442 ISSN 2632-3168 £5 where sold Time to Uncover the Histories of Occupation and Oppression OLSI JAZEXHI DENIJAL JEGI IAN ALMOND MASSOUD SHADJAREH ć How did Israel go from Liberating Lebanon Terrorism Got COVID: Why We Need to Get Pariah to become and Decolonising the Or, The Constant- Beyond Regimes of God’s Chosen Nation Discourse that Threat News-Culture Anti-terrorism, and in the Balkans? Occupies It We Live In Fast In the Name of Allah, the Most Beneficent, the Most Merciful he recent Israeli war on Palestinians cally the ‘threat’ of terrorism that most of Contents: has highlighted once more – despite us in the Westernised world had become the best efforts of powerful countries accustomed to on a daily basis for almost and compliant media – the brutality of the two decades. That is, until the beginning TIsraeli project of occupation. As with pre - of the pandemic. Having fallen off the 3 Olsi Jazexhi : vious such wars, the limelight soon fades news agenda almost entirely, Almond ar - How did Israel go from Pariah as ceasefires are called, and the ongoing gues that the Coronavirus crisis has ex - stifling of Palestinian life and aspirations, posed the news media as complicit in to become God’s Chosen by routine physical and psychological vio - promoting an exaggerated image of the Nation in the Balkans? lence remains invisible. The strategies – dangers society faces from ‘terrorism’. This military and political – that mask this bru - exaggeration serves the interests of elites, tality and injustice feature in two of this is - whilst simultaneously providing salacious sues’ articles.