Long Wait and Other Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Able to You and Your Family

1. Events and Activity Guide April - June Parks and Recreation Bristol, Tennessee Inside This Issue Welcome to the Bristol, Tennessee Parks & Recreation’s activity guide. We hope you will enjoy the many amenities and programs PG.4 available to you and your family. We continue to encourage you to make positive lifestyle choices in your pursuit of healthy and Check out our parks, active living. Select one of our active programs and get your body playgrounds and facilities moving, or get outside and enjoy one of our well-maintained parks. We believe that staying active and being more health- conscious can be sustained over time through being active. PG.6 Steele Creek Golf Course PG.13 Senior Adult Trips PG.25 Movies in the Park PG.30 Senior Lunch Program PG. 34 Swim Lesson Information The Downtown Center is a multi-use venue located in the middle of historic downtown Bristol. The center hosts the Sounds of Summer Concert Series each year beginning in June and going through the end of September. It is also home to State Street Farmer’s Market. YOU CAN RENT OUR PICNIC SHELTERS! they are great for family reunions birthday parties or get togethers! Check out details on page 5 Contact Information Table of Contents Parks and Recreation Director: 2 - General Information 3 - Contact Information Terry Napier- 423- 764-4023 4 - Parks, Playground & Facilities 5 - Rentals & Rates Recreation: 6 - Steele Creek Golf Course Beth Carter- 423-989-5275 7 - Steele Creek Disc Golf Karen McCook-423-764-4048 8- Haynesfield Pool Hours 9-12 - Senior Adult Weekly -

Jazzweek Jazz Album Chart Sept

airplay data JazzWeek Jazz Album Chart Sept. 11, 2006 powered by TW LW 2W Peak Artist Release Label TP LP +/- Weeks Stations Adds 1 1 1 1 Dr. Lonnie Smith Jungle Soul Palmetto 367 398 -31 7 73 0 2 5 NR 2 Cedar Walton One Flight Down HighNote 251 191 60 2 54 14 3 4 4 3 Frank Morgan Reflections HighNote 230 193 37 7 58 2 4 2 2 1 Regina Carter I’ll Be Seeing You (A Sentimental Journey) Verve Music Group 228 245 -17 11 61 0 5 3 3 3 Jon Faddis Teranga Koch 226 200 26 11 50 4 6 20 30 6 Winard Harper Make It Happen Piadrum 208 156 52 4 53 2 7 6 5 5 Brad Mehldau Trio House On Hill Nonesuch 189 190 -1 8 43 1 7 NR NR 7 Houston Person & Bill Charlap You Taught My Heart To Sing HighNote 189 77 112 1 50 17 9 7 14 7 Anton Schwartz Radiant Blue Anton Jazz 185 185 0 3 48 3 10 27 8 8 Buck Hill Relax Severn 181 139 42 6 47 1 11 8 16 8 Freddy Cole Because Of You HighNote 179 175 4 7 56 1 12 9 21 9 Scott Hamilton Nocturnes and Serenades Concord Jazz 178 174 4 5 49 3 12 18 18 12 The Chris Walden Big Band No Bounds Origin 178 158 20 7 42 1 12 15 13 12 Ray Barretto Standards Rican-ditioned Zoho Music 178 167 11 4 51 3 15 28 26 15 Joe Lovano Streams of Expression Blue Note 166 136 30 4 44 3 15 16 9 6 Hank Jones & Frank Wess Hank & Frank Lineage Records 166 164 2 13 37 0 17 9 6 5 Gordon Goodwin’s Big Phat Band The Phat Pack Immergent 165 174 -9 6 38 2 18 29 14 5 Eric Reed Here MAXJAZZ 163 134 29 14 46 1 19 13 6 1 Roy Hargrove Nothing Serious Verve Music Group 161 172 -11 19 56 1 20 33 39 20 Ann Hampton Calloway Blues In The Night Telarc 160 125 35 3 43 6 21 25 -

Star Channels, May 20-26

MAY 20 - 26, 2018 staradvertiser.com LEGAL EAGLES Sandra’s (Britt Robertson) confi dence is shaken when she defends a scientist accused of spying for the Chinese government in the season fi nale of For the People. Elsewhere, Adams (Jasmin Savoy Brown) receives a compelling offer. Chief Judge Nicholas Byrne (Vondie Curtis-Hall) presides over the Southern District of New York Federal Court in this legal drama, which wraps up a successful freshman season. Airing Tuesday, May 22, on ABC. WE’RE LOOKING FOR PEOPLE WHO HAVE SOMETHING TO SAY. Are you passionate about an issue? An event? A cause? ¶ũe^eh\Zga^eirhn[^a^Zk][r^fihp^kbg`rhnpbmama^mkZbgbg`%^jnbif^gm olelo.org Zg]Zbkmbf^rhng^^]mh`^mlmZkm^]'Begin now at olelo.org. ON THE COVER | FOR THE PEOPLE Case closed ABC’s ‘For the People’ wraps Deavere Smith (“The West Wing”) rounds example of how the show delves into both the out the cast as no-nonsense court clerk Tina professional and personal lives of the charac- rookie season Krissman. ters. It’s a formula familiar to fans of Shonda The cast of the ensemble drama is now part Rhimes, who’s an executive producer of “For By Kyla Brewer of the Shondaland dynasty, which includes hits the People,” along with Davies, Betsy Beers TV Media “Grey’s Anatomy,” “Scandal” and “How to Get (“Grey’s Anatomy”), Donald Todd (“This Is Us”) Away With Murder.” The distinction was not and Tom Verica (“How to Get Away With here’s something about courtroom lost on Rappaport, who spoke with Murder”). -

A Process Evaluation of the NCVLI Victims' Rights Clinics

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Finally Getting Victims Their Due: A Process Evaluation of the NCVLI Victims’ Rights Clinics Author: Robert C. Davis, James Anderson, Julie Whitman, Susan Howley Document No.: 228389 Date Received: September 2009 Award Number: 2007-VF-GX-0004 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Finally Getting Victims Their Due: A Process Evaluation of the NCVLI Victims’ Rights Clinics Abstract Robert C. Davis James Anderson RAND Corporation Julie Whitman Susan Howley National Center for Victims of Crime August 29, 2009 This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. -

A Country Doctor and Selected Stories and Sketches, by Sarah Orne Jewett

The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Country Doctor and Selected Stories and Sketches, by Sarah Orne Jewett This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: A Country Doctor and Selected Stories and Sketches Author: Sarah Orne Jewett Release Date: March 8, 2005 [EBook #15294] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A COUNTRY DOCTOR AND *** Produced by Suzanne Shell, Wendy Bertsch and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at www.pgdp.net. A COUNTRY DOCTOR AND SELECTED STORIES AND SKETCHES by Sarah Orne Jewett Published 1884 Click here for SELECTED STORIES AND SKETCHES A Country Doctor CONTENTS I. THE LAST MILE II. THE FARM-HOUSE KITCHEN III. AT JAKE AND MARTIN'S IV. LIFE AND DEATH V. A SUNDAY VISIT VI. IN SUMMER WEATHER VII. FOR THE YEARS TO COME VIII. A GREAT CHANGE IX. AT DR. LESLIE'S X. ACROSS THE STREET XI. NEW OUTLOOKS XII. AGAINST THE WIND XIII. A STRAIGHT COURSE XIV. MISS PRINCE OF DUNPORT XV. HOSTESS AND GUEST XVI. A JUNE SUNDAY XVII. BY THE RIVER XVIII. A SERIOUS TEA-DRINKING XIX. FRIEND AND LOVER XX. ASHORE AND AFLOAT XXI. AT HOME AGAIN I THE LAST MILE It had been one of the warm and almost sultry days which sometimes come in November; a maligned month, which is really an epitome of the other eleven, or a sort of index to the whole year's changes of storm and sunshine. -

Kappale Artisti

14.7.2020 Suomen suosituin karaokepalvelu ammattikäyttöön Kappale Artisti #1 Nelly #1 Crush Garbage #NAME Ednita Nazario #Selˆe The Chainsmokers #thatPOWER Will.i.am Feat Justin Bieber #thatPOWER Will.i.am Feat. Justin Bieber (Baby I've Got You) On My Mind Powderˆnger (Barry) Islands In The Stream Comic Relief (Call Me) Number One The Tremeloes (Can't Start) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue (Doo Wop) That Thing Lauren Hill (Every Time I Turn Around) Back In Love Again LTD (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Brandy (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Bryan Adams (Hey Won't You Play) Another Somebody Done Somebody Wrong Song B. J. Thomas (How Does It Feel To Be) On Top Of The W England United (I Am Not A) Robot Marina & The Diamonds (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction The Rolling Stones (I Could Only) Whisper Your Name Harry Connick, Jr (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew (If Paradise Is) Half As Nice Amen Corner (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Shania Twain (I'll Never Be) Maria Magdalena Sandra (It Looks Like) I'll Never Fall In Love Again Tom Jones (I've Had) The Time Of My Life Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes (I've Had) The Time Of My Life Bill Medley-Jennifer Warnes (I've Had) The Time Of My Life (Duet) Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes (Just Like) Romeo And Juliet The Re˜ections (Just Like) Starting Over John Lennon (Marie's The Name) Of His Latest Flame Elvis Presley (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Elvis Presley (Reach Up For The) Sunrise Duran Duran (Shake, Shake, Shake) Shake Your Booty KC And The Sunshine Band (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay Otis Redding (Theme From) New York, New York Frank Sinatra (They Long To Be) Close To You Carpenters (We're Gonna) Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & His Comets (Where Do I Begin) Love Story Andy Williams (You Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears (You Gotta) Fight For Your Right (To Party!) The Beastie Boys 1+1 (One Plus One) Beyonce 1000 Coeurs Debout Star Academie 2009 1000 Miles H.E.A.T. -

Eastern Progress 1992-1993 Eastern Progress

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Eastern Progress 1992-1993 Eastern Progress 3-4-1993 Eastern Progress - 04 Mar 1993 Eastern Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: http://encompass.eku.edu/progress_1992-93 Recommended Citation Eastern Kentucky University, "Eastern Progress - 04 Mar 1993" (1993). Eastern Progress 1992-1993. Paper 23. http://encompass.eku.edu/progress_1992-93/23 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Eastern Progress at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Eastern Progress 1992-1993 by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ACCENT ACTIVITIES SPORTS WEEKEND FORECAST FRIDAV: Rain likely, Clothes galore ^^d& Mountain music OVC in Rupp high In the 40» Consignment shop offers *^F^Tl Colonels hope for a SATURDAY: Dry and cool, Alabama gives crowd high In the 40s variety of duds for low prices Wr money's worth tournament victory SUNDAY: Dry, high in the Page B-l Page B-5 Page B-6 1 Ztiakl THE EASTERN PROGRESS Vol. 71/No. 23 14 pages March 4,1993 Student publication of Eastern Kentucky University, Richmond, Ky. 40475 The Eastern Progress, 1993 Midterm grades, new grading policy spark debate ■ Faculty senate reports or papers or providing written inform the students of their progress ■ Student senate implementing the system were rea- there is no 'grandma clause' in it. If notification of clinical performance, at least once prior to midterm, this sons cited in the proposal for forming someone receives half their grades votes for student said Russ Enzic, associate vice presi- could be done simply by returning one calls for the new committee. -

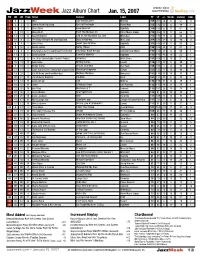

Jazzweek Jazz Album Chart Jan

airplay data JazzWeek Jazz Album Chart Jan. 15, 2007 powered by TW LW 2W Peak Artist Release Label TP LP +/- Weeks Stations Adds 1 2 7 1 MB3 Jazz Hits Volume 1 Mel Bay 259 201 58 8 57 0 2 3 2 2 Jimmy Heath Big Band Turn Up The Heath Planet Arts 255 192 63 8 49 1 3 3 3 1 Steve Turre Keep Searchin’ HighNote 254 192 62 11 61 2 4 1 10 1 Diana Krall From This Moment On Verve Music Group 218 205 13 17 55 0 5 13 13 5 Russell Malone Live at Jazz Standard, Vol. One MAXJAZZ 212 135 77 8 56 3 6 10 9 2 The Dizzy Gillespie All-Star Big Band Dizzy’s Business MCG Jazz 204 150 54 15 49 0 7 6 4 1 John Hicks Sweet Love Of Mine HighNote 203 156 47 11 55 2 8 9 16 4 Sonny Rollins Sonny, Please Doxy 198 152 46 11 57 1 9 11 8 3 Ray Charles & The Count Basie Orchestra Ray Sings, Basie Swings Concord/Hear Music 193 146 47 14 59 1 10 11 6 6 Dave Valentin Come Fly With Me HighNote 192 146 46 10 53 1 11 5 12 5 The Brian Lynch/Eddie Palmieri Project Simpatico Artist Share 181 169 12 15 51 2 12 15 19 12 Bob DeVos Shifting Sands Savant 178 131 47 6 48 3 13 7 10 2 Stefon Harris African Tarantella Blue Note 159 155 4 14 45 0 14 13 13 2 Louis Hayes & The Cannonball Legacy Band Maximum Firepower Savant 152 135 17 15 40 1 15 19 20 2 Pat Metheny and Brad Mehldau Metheny Mehldau Nonesuch 151 116 35 16 43 1 15 20 17 15 The Brubeck Brothers Intutition Koch 151 114 37 6 46 1 17 17 22 17 Lynne Arriale Live Motema 146 119 27 12 39 1 18 18 23 14 Tomo I’ll Always Know Torii Records 135 117 18 11 34 1 19 22 28 16 Ben Riley Memories of T Concord 133 105 28 10 34 1 20 23 26 2 Cedar -

Æ‚‰É”·ȯLj¾é “ Éÿ³æ¨‚Å°ˆè¼¯ ĸ²È¡Œ (ĸ“Ⱦ

æ‚‰é” Â·è¯ çˆ¾é “ 音樂專輯 串行 (专辑 & æ—¶é— ´è¡¨) Spectrum https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/spectrum-7575264/songs The Electric Boogaloo Song https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-electric-boogaloo-song-7731707/songs Soundscapes https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/soundscapes-19896095/songs Breakthrough! https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/breakthrough%21-4959667/songs Beyond Mobius https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/beyond-mobius-19873379/songs The Pentagon https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-pentagon-17061976/songs Composer https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/composer-19879540/songs Roots https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/roots-19895558/songs Cedar! https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/cedar%21-5056554/songs The Bouncer https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-bouncer-19873760/songs Animation https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/animation-19872363/songs Duo https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/duo-30603418/songs The Maestro https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-maestro-19894142/songs Voices Deep Within https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/voices-deep-within-19898170/songs Midnight Waltz https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/midnight-waltz-19894330/songs One Flight Down https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/one-flight-down-20813825/songs Manhattan Afternoon https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/manhattan-afternoon-19894199/songs Soul Cycle https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/soul-cycle-7564199/songs -

Prestige Label Discography

Discography of the Prestige Labels Robert S. Weinstock started the New Jazz label in 1949 in New York City. The Prestige label was started shortly afterwards. Originaly the labels were located at 446 West 50th Street, in 1950 the company was moved to 782 Eighth Avenue. Prestige made a couple more moves in New York City but by 1958 it was located at its more familiar address of 203 South Washington Avenue in Bergenfield, New Jersey. Prestige recorded jazz, folk and rhythm and blues. The New Jazz label issued jazz and was used for a few 10 inch album releases in 1954 and then again for as series of 12 inch albums starting in 1958 and continuing until 1964. The artists on New Jazz were interchangeable with those on the Prestige label and after 1964 the New Jazz label name was dropped. Early on, Weinstock used various New York City recording studios including Nola and Beltone, but he soon started using the Rudy van Gelder studio in Hackensack New Jersey almost exclusively. Rudy van Gelder moved his studio to Englewood Cliffs New Jersey in 1959, which was close to the Prestige office in Bergenfield. Producers for the label, in addition to Weinstock, were Chris Albertson, Ozzie Cadena, Esmond Edwards, Ira Gitler, Cal Lampley Bob Porter and Don Schlitten. Rudy van Gelder engineered most of the Prestige recordings of the 1950’s and 60’s. The line-up of jazz artists on Prestige was impressive, including Gene Ammons, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Eric Dolphy, Booker Ervin, Art Farmer, Red Garland, Wardell Gray, Richard “Groove” Holmes, Milt Jackson and the Modern Jazz Quartet, “Brother” Jack McDuff, Jackie McLean, Thelonious Monk, Don Patterson, Sonny Rollins, Shirley Scott, Sonny Stitt and Mal Waldron. -

Weekly

May WEEKLY SUN MON Tur INFO THU FRISAT no, 1 6 7 23 45 v4<..\k, 9 10 1112 13 14 15 $3.00 As?,9030. 8810 85 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 $2.80 plus .20 GST A 2_4 2330 243125 26 27 28 29 Volume 57 No. 14 -512 13 AA22. 2303 Week Ending April 17, 1993 .k2't '1,2. 282 25 No. 1 ALBUM ARE YOU GONNA GO MY WAY Lenny Kravitz TELL ME WHAT YOU DREAM Restless Heart WHO IS IT Michael Jackson SOMEBODY LOVE ME Michael W. Smith LOOKING THROUGH ERIC CLAPTON PATIENT EYES Unplugged PM Dawn Reprise - CDW-45024-P I FEEL YOU Depeche Mode LIVING ON THE EDGE Aerosmith YOU BRING ON THE SUN Londonbeat RUNNING ON FAITH CAN'T DO A THING Eric Clapton (To Stop Me) Chris Isaak to LOOK ME IN THE EYES oc Vivienne Williams IF YOU BELIEVE IN ME thebeANts April Wine coVapti FLIRTING WITH A HEARTACHE Ckade Dan Hill LOITA LOVE TO GIVE 0etex s Daniel Lanois oll.v-oceve,o-c1e, DON'T WALK AWAY Jade NOTHIN' MY LOVE CAN'T FIX DEPECHE MODE 461100'. Joey Lawrence ; Songs Of Faith And Devotion c.,25seNps CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 10,000 FLYING THE CULT Blue Rodeo Pure Cult BIG TIME DWIGHT YOAKAM I PUT A SPELL ON YOU LEONARD COHEN This Time Bryan Ferry The Future ALBUM PICK DANIEL LANOIS HARBOR LIGHTS ALADDIN . For The Beauty Of Wynona Bruce Hornsby Soundtrack HOTHOUSE FLOWERS COUNTRY Songs From The Rain ADDS HIT PICK JUST AS I AM Ricky Van Shelton No. -

Cledus T. Judd to Dixie Chicks

Sound Extreme Entertainment Karaoke Show with Host 828-551-3519 [email protected] www.SoundExtreme.net In The Style Of Title Genre Cledus T. Judd If Shania Was Mine Country Cledus T. Judd Jackson (Alan That Is) Country Cledus T. Judd My Cellmate Thinks I'm Sexy Country & Pop Cledus T. Judd Shania I'm Broke Country Cledus T. Judd Tree's On Fire Holiday Cledus T. Judd Where The Grass Don't Grow Country Click Five, The Just The Girl Country & Pop Climax Blues Band Couldn't Get It Right Pop / Rock Clint Black Better Man Country & Pop Clint Black Burn One Down Country Clint Black Desperado Country Clint Black Killin' Time Country & Pop Clint Black Loving Blind Country Clint Black Nobody's Home Country Clint Black Nothings News Country Clint Black One More Payment Country Clint Black Put Yourself In My Shoes Country & Pop Clint Black Strong One, The Country Clint Black This Nightlife Country Clint Black We Tell Ourselves Country Clint Black When My Ship Comes In Country Clint Black Where Are You Now Country Clint Daniels Letter, The Country & Pop Clint Daniels When I Grow Up Country Clint Holmes Playground In My Mind Pop Clinton Gregory If It Weren't For Country Music (I'd Go Crazy) Country Clinton Gregory One Shot At A Time Country Clinton Gregory Rocking The Country Country Clinton Gregory Satisfy Me And I'll Satisfy You Country Club Nouveau Lean On Me Pop Coasters, The Charlie Brown Country & Pop Coasters, The Little Egypt Oldies Sound Extreme Entertainment www.SoundExtreme.net www.SoundExtremeWeddings.com www.CrocodileSmile.net 360 King Rd.