Econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

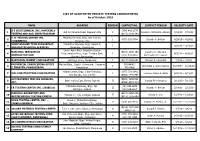

III III III III LIST of ACCREDITED PRIVATE TESTING LABORATORIES As of October 2019

LIST OF ACCREDITED PRIVATE TESTING LABORATORIES As of October 2019 NAME ADDRESS REGION CONTACT NO. CONTACT PERSON VALIDITY DATE A’S GEOTECHNICAL INC. MATERIALS (074) 442-2775 1 Old De Venecia Road, Dagupan City I Dioscoro Richard B. Alviedo 7/16/19 – 7/15/21 TESTING AND SOIL INVESTIGATION (0917) 1141-343 E. B. TESTING CENTER INC. McArthur Hi-way, Brgy. San Vicente, 2 I (075) 632-7364 Elnardo P. Bolivar 4/29/19 – 4/28/21 (URDANETA) Urdaneta City JORIZ GROUND TECH SUBSURFACE MacArthur Highway, Brgy. Surabnit, 3 I 3/20/18 – 3/19/20 AND GEOTECHNICAL SERVICES Binalonan, Pangasinan Lower Agno River Irrigation System NATIONAL IRRIGATION (0918) 8885-152 Ceferino C. Sta. Ana 4 Improvement Proj., Brgy. Tomana East, I 4/30/19 – 4/29/21 ADMINISTRATION (075) 633-3887 Rommeljon M. Leonen Rosales, Pangasinan 5 NORTHERN CEMENT CORPORATION Labayug, Sison, Pangasinan I (0917) 5764-091 Vincent F. Cabanilla 7/3/19 – 7/2/21 PROVINCIAL ENGINEERING OFFICE Malong Bldg., Capitol Compound, Lingayen, 542-6406 / 6 I Antonieta C. Delos Santos 11/23/17 – 11/22/19 (LINGAYEN, PANGASINAN) Pangasinan 542-6468 Valdez Center, Brgy. 1 San Francisco, (077) 781-2942 7 VVH CONSTRUCTION CORPORATION I Francisco Wayne B. Butay 6/20/19 – 6/19/21 San Nicolas, Ilocos Norte (0966) 544-8491 ACCURATEMIX TESTING SERVICES, (0906) 4859-531 8 Brgy. Muñoz East, Roxas, Isabela II Juanita Pine-Ordanez 3/11/19 – 3/10/21 INC. (0956) 4078-310 Maharlika Highway, Brgy. Ipil, (02) 633-6098 9 EB TESTING CENTER INC. (ISABELA) II Elnardo P. Bolivar 2/14/18 – 2/13/20 Echague, Isabela (02) 636-8827 MASUDA LABORATORY AND (0917) 8250-896 10 Marana 1st, City of Ilagan, Isabela II Randy S. -

The City in a Forest Indonesia

; Lies in the heart of the Puerto Princesa City WŚŝůŝƉƉŝŶĞ͛Ɛ͞>ĂƐƚĐŽůŽŐŝĐĂů Philippines &ƌŽŶƚŝĞƌ͟ Urban Area ; Land Area: 253,984 Hectares A Model in Sustainable Development Palawan Puerto Princesa City ; Population: 232,454 ; Annual Growth rate: 3.68% ; Urban Area is roughly 6% of ƚŚĞŝƚLJ͛ƐƚŽƚĂůůĂŶĚĂƌĞĂ Philippines ; 77% of the population reside Malaysia Brunei in the urban area The City in a Forest Indonesia TERRESTRIAL ; Richly endowed with natural resources ; Forest - 72% ; Home of the World famous Underground River ; Primary - 7.38% ; Large developable land for agriculture and agro-industries ; Secondary - 51.67% ; Good and stable peace and order ; Limestone - 0.85% ; Extra Local Authority over Environmental Issues under ; Ultramafic - 12.23% the SEP Law (Republic Act 7611) otherwise known as the Strategic Environmental Plan for Palawan ; Built-up - 1.78% COASTAL/MARINE ; Mangrove - 5,896 Has. ; The fragile environment ; Coral Reef - 3,074 Has. ; Land speculation ; Dense Seagrass - 836 Has. ; Emergence of other competitive tourist destinations ; Sparse Seagrass- 880 Has. ; Low agricultural production and productivity ; High Internal Revenue Allotment (IRA) Dependency Ratio ; TOURISM ; 2009 Tourist Income: US$50M Vision: ; 2009 Tourist Arrivals: 268,942 Towards a Model City ; Annual Growth Rate: 20% in Sustainable ; Most Number Foreign Visitors: American, Korean, German, Development Japanese, Chinese, Canadian, Australian, French & Swiss ; FISHING ; Coastline stretches over 416Kms. City Brand: ; Coastal waters cover 327,583 Has. ; Supplies more than 50% of fish The City in a Forest requirements in Metro Manila AWARDS & RECOGNITIONS of PUERTO PRINCESA CITY UNITED NATIONS GLOBAL 500 AWARD MAJOR AWARDS Hall of Fame Award Clean and Green Program :DVDPLFURFRVPRIWKH3KLOLSSLQH¶V Galing Pook Hall of Fame Award environmental drift..our forests and our seas were the favorite sources of income From A.I.M. -

Philippine Port Authority Contracts Awarded for CY 2018

Philippine Port Authority Contracts Awarded for CY 2018 Head Office Project Contractor Amount of Project Date of NOA Date of Contract Procurement of Security Services for PPA, Port Security Cluster - National Capital Region, Central and Northern Luzon Comprising PPA Head Office, Port Management Offices (PMOs) of NCR- Lockheed Global Security and Investigation Service, Inc. 90,258,364.20 27-Nov-19 23-Dec-19 North, NCR-South, Bataan/Aurora and Northern Luzon and Terminal Management Offices (TMO's) Ports Under their Respective Jurisdiction Proposed Construction and Offshore Installation of Aids to Marine Navigation at Ports of JARZOE Builders, Inc./ DALEBO Construction and General. 328,013,357.76 27-Nov-19 06-Dec-19 Estancia, Iloilo; Culasi, Roxas City; and Dumaguit, New Washington, Aklan Merchandise/JV Proposed Construction and Offshore Installation of Aids to Marine Navigation at Ports of Lipata, Goldridge Construction & Development Corporation / JARZOE 200,000,842.41 27-Nov-19 06-Dec-19 Culasi, Antique; San Jose de Buenavista, Antique and Sibunag, Guimaras Builders, Inc/JV Consultancy Services for the Conduct of Feasibility Studies and Formulation of Master Plans at Science & Vision for Technology, Inc./ Syconsult, INC./JV 26,046,800.00 12-Nov-19 16-Dec-19 Selected Ports Davila Port Development Project, Port of Davila, Davila, Pasuquin, Ilocos Norte RCE Global Construction, Inc. 103,511,759.47 24-Oct-19 09-Dec-19 Procurement of Security Services for PPA, Port Security Cluster - National Capital Region, Central and Northern Luzon Comprising PPA Head Office, Port Management Offices (PMOs) of NCR- Lockheed Global Security and Investigation Service, Inc. 90,258,364.20 23-Dec-19 North, NCR-South, Bataan/Aurora and Northern Luzon and Terminal Management Offices (TMO's) Ports Under their Respective Jurisdiction Rehabilitation of Existing RC Pier, Port of Baybay, Leyte A. -

Directory of Participants 11Th CBMS National Conference

Directory of Participants 11th CBMS National Conference "Transforming Communities through More Responsive National and Local Budgets" 2-4 February 2015 Crowne Plaza Manila Galleria Academe Dr. Tereso Tullao, Jr. Director-DLSU-AKI Dr. Marideth Bravo De La Salle University-AKI Associate Professor University of the Philippines-SURP Tel No: (632) 920-6854 Fax: (632) 920-1637 Ms. Nelca Leila Villarin E-Mail: [email protected] Social Action Minister for Adult Formation and Advocacy De La Salle Zobel School Mr. Gladstone Cuarteros Tel No: (02) 771-3579 LJPC National Coordinator E-Mail: [email protected] De La Salle Philippines Tel No: 7212000 local 608 Fax: 7248411 E-Mail: [email protected] Batangas Ms. Reanrose Dragon Mr. Warren Joseph Dollente CIO National Programs Coordinator De La Salle- Lipa De La Salle Philippines Tel No: 756-5555 loc 317 Fax: 757-3083 Tel No: 7212000 loc. 611 Fax: 7260946 E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] Camarines Sur Brother Jose Mari Jimenez President and Sector Leader Mr. Albino Morino De La Salle Philippines DEPED DISTRICT SUPERVISOR DEPED-Caramoan, Camarines Sur E-Mail: [email protected] Dr. Dina Magnaye Assistant Professor University of the Philippines-SURP Cavite Tel No: (632) 920-6854 Fax: (632) 920-1637 E-Mail: [email protected] Page 1 of 78 Directory of Participants 11th CBMS National Conference "Transforming Communities through More Responsive National and Local Budgets" 2-4 February 2015 Crowne Plaza Manila Galleria Ms. Rosario Pareja Mr. Edward Balinario Faculty De La Salle University-Dasmarinas Tel No: 046-481-1900 Fax: 046-481-1939 E-Mail: [email protected] Mr. -

Climate Change Projections for Local Planning

Climate Change Projections for Local Planning: A Practical Application of Overlay Analysis and Synthetic Impact Assessment in the Cities of Batangas, General Santos, Legazpi, Puerto Princesa and Tagbilaran Strengthening Urban Resilience for Growth with Equity (SURGE) Project CONTRACT NO. AID-492-H-15-00001 AUGUST 8, 2018 This report is made possible with the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of the International City/County Management Association and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. USAID Strengthening Urban Resilience for Growth with Equity (SURGE) Project Page 1 Climate Change Projections for Local Planning: A Practical Application of Overlay Analysis and Synthetic Impact Assessment in the Cities of Batangas, General Santos, Legazpi, Puerto Princesa and Tagbilaran Strengthening Urban Resilience for Growth with Equity (SURGE) Project CONTRACT NO. AID-492-H-15-00001 Program Title: USAID/SURGE Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID/Philippines Contract Number: AID-492-H-15-00001 Contractor: International City/County Management Association (ICMA) Date of Publication: August 8, 2018 USAID Strengthening Urban Resilience for Growth with Equity (SURGE) Project Page 2 Table of Contents ACRONYMS 10 LIST OF TABLES 11 LIST OF FIGURES 11 LIST OF BATANGAS CITY MAPS 11 LIST OF GENERAL SANTOS CITY MAPS 12 LIST OF LEGAZPI CITY MAPS 13 LIST OF PUERTO PRINCESA CITY MAPS 13 LIST OF TAGBILARAN CITY MAPS 14 ABSTRACT 15 I. INTRODUCTION 16 Background of SURGE 16 Translation and Projections 16 Climate Projections in the Philippines 17 Synthesis of Climate Change Impacts 18 Selecting Priority Sectors 18 II. -

Bacolod-Silay Airfield Lighting System Precision Approach Path Indicator

LIST OF ELECTRO-MECHANICAL SYSTEMS/EQUIPMENT INSTALLED IN AIRPORTS NATIONWIDE AIRPORT SYSTEM/EQUIPMENT Bacolod-Silay Airfield Lighting System ▪ Precision Approach Path Indicator ▪ Precision Approach Lighting System ▪ Simple Approach Lighting System ▪ Runway Edge Lights ▪ Taxiway Edge Lights ▪ Runway Threshold/End Lights ▪ Stopway and Wingbar Lights ▪ Sequential Flashing Lights ▪ Turning Pad Lights ▪ Apron Flood Lights ▪ Wind Direction Indicator Light ▪ Aerodrome Beacon ▪ Spot Number Lights ▪ Taxiway Guidance Sign Emergency and Standby Power Systems Baguio Airfield Lighting System ▪ Precision Approach Path Indicator Emergency and Standby Power Systems Basco Airfield Lighting System ▪ Precision Approach Path Indicator ▪ Aerodrome Beacon Emergency and Standby Power Systems Busuanga Airfield Lighting System ▪ Precision Approach Path Indicator Emergency and Standby Power Systems Butuan Airfield Lighting System ▪ Precision Approach Path Indicator ▪ Simple Approach Lighting System ▪ Wind Direction Indicator Light ▪ Runway Edge Lights ▪ Taxiway Edge Lights ▪ Runway Threshold/End Lights ▪ Apron Flood Lights ▪ Aerodrome Beacon Emergency and Standby Power Systems Catarman Airfield Lighting System ▪ Precision Approach Path Indicator Emergency and Standby Power Systems Caticlan Airfield Lighting System c/o TADHC ▪ Precision Approach Path Indicator ▪ Runway Threshold Identification Lights ▪ Wind Direction Indicator Light ▪ Aerodrome Beacon ▪ Runway Edge Lights ▪ Taxiway Edge Lights ▪ Runway Threshold/End Lights ▪ Runway Directional Signages ▪ Turning -

Enhancing the ASEAN Community Through Town Twinning Arrangements

Presented at the DLSU Research Congress 2017 De La Salle University, Manila, Philippines June 20 to 22, 2017 Enhancing the ASEAN Community through Town Twinning Arrangements Ma. Divina Gracia Z. Roldan Political Science Department, De La Salle University [email protected] Abstract: Philippine external relations is commonly perceived as the sole domain of national government. Yet given the move towards Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) integration and in light of current global trends where diverse players take on a role in regional affairs, there are increased opportunities for the Philippines to strengthen ties with its neighbors not only on a national but sub- national level. This paper explores how the town twinning or sister city program provides a mechanism for Philippine local government units to establish links with their ASEAN counterparts to promote trade, technical, cultural, and educational exchanges. Using document analysis and a case study approach, the paper discusses the processes and outcomes of town twinning arrangements with Cebu as a case in point. While there is much potential for increasing inflows of material resources and human capital through this mechanism, it is noted that the Philippine local government units have not maximized the benefits of town twinning arrangements within ASEAN. Only four Philippine cities namely, Bacolod, Cebu, Puerto Princesa, and Vigan have sister cities with only two ASEAN countries which are Malaysia and Indonesia. The paper argues that there is a need to impress upon policymakers that non-state actors such as, local government units, can be effective players in bringing about stronger ties in the region by means of enhanced bilateral cooperation among ASEAN towns and cities. -

Philippines PBN Implementation Plan 2011

CCIIVVIILL AAVVIIAATTIIOONN AAUUTTHHOORRIITTYY OOFF TTHHEE PPHHIILLIIPPPPIINNEESS PPBBNN IImmpplleemmeennttaattiioonn PPllaann VERSION 2.0 AIRSPACE & FLIGHT PROCEDURE DESIGN DIVISION – AIR TRAFFIC SERVICE CCoonntteennttss 1. Introduction • ICAO Mandate and PBN Global Perspective • Status of RNAV Operations in the Philippine 2. Objectives 3. Challenges 4. Development of PBN Implementation Plan 5. Implementation Plan 6. Benefits of PBN 7. Safety Assessment Civil Aviation Authority of the Philippines | Airspace and Flight Procedure Design Division 2 IInnttrroodduuccttiioonn Airspace Capacity The relentless increase of oil prices and the global financial meltdown did not dampen the air traffic growth in the Philippines. The country’s premier airport, Ninoy Aquino International Airport (NAIA), In order to decongest traffic in NAIA, ATC posted 6.46% increase in aircraft movement for the year 2010. Aircraft movement in NAIA has procedures and infrastructure improvements are more than doubled in the last ten years. currently being implemented. Runway 13 of NAIA has been upgraded to allow instrument operations. Traffic in NAIA reaches its maximum capacity Simultaneous operations between Runway 06/24 during peak hours resulting to flight delays. This and Runway 13 became possible with the increase in international and domestic traffic not implementation of LAHSO operations which only in NAIA but in other airports in the country allowed aircraft weighing 25,000 kilograms and can be attributed to the aggressive below to land on Runway 13 during VMC thereby promotion of low cost air travel attracting more increasing runway capacity. passengers who used to take the services of the shipping lines. Air Traffic Flow Management (ATFM) was implemented on the second quarter of 2010 with the same objective of increasing airport capacity while still ensuring safety and efficiency of operations. -

Ocean Observing and Information Systems in the Philippines

Ocean observing and information systems in the Philippines Cesar Villanoy Marine Science Institute University of the Philippines Philippine archipelago consists of complex system of islands, sea passages and basins with complicated topography Orographic effects important making it also challenging to conduct ocean and atmosphere observations Spatial variable wind stress produces sub-meso-scale ocean features. From Flament, Chavanne Tracks and intensity of all tropical cyclones http://eoimages.gsfc.nasa.gov/images/imagerecords/7000/7079/tropical_cyclone_map_l rg.gif Hottest of the Hotspots Observation programs • National Mapping and Resource Information Authority (operational agency for oceanograpy-also designated as the national oceanographic data center) • Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical, Astronomical Services Administration (operational meteorological agency) • Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources • Research-based observations (e.g. academic institutions) • coral monitoring, water quality in aquaculture areas • Meteorology/Oceanography • Project NOAH NAMRIA TIDE STATIONS BASCO SAN VICENTE EXISTING TIDE STATIONS = 47 CURRIMAO IOC NEAR-REAL-TIME TELEMETRY STATIONS = 6 PORT JOSE PANGANIBA SAN FERNANDO NEAR-REAL-TIME TELEMETRY STATIONS = 34 REA N MARIVELES L VIRA NON-TELEMETRY STATIONS = 7 C SUBIC BALANACA N BULA BALE LEGAZP N R I CALAPAN MANILA CORON LUBANG SAN JOSE MAMBURAO N.SAMAR CATBALOGA ODIONGAN SAN MASBATE EL NIDO BATANGAS CARLOS N SAN JOSE PULUPANDAN TACLOBAN CATICLAN CEBU SAN JOSE PUERTO PRINCESA ANTIQUE TANDAG BALINTANG -

Assessment of the Vulnerabilities and Local Capacities of Cities Development Initiative (Cdi) Cities for Building Urban Resilience

ASSESSMENT OF THE VULNERABILITIES AND LOCAL CAPACITIES OF CITIES DEVELOPMENT INITIATIVE (CDI) CITIES FOR BUILDING URBAN RESILIENCE Strengthening Urban Resilience for Growth with Equity (SURGE) Project CONTRACT NO. AID-492-H-15-00001 DECEMBER 23, 2016 This report is made possible ort of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). This report was prepared by the International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives - Local Governments for Sustainability Southeast Asia Secretariat (ICLEI- SEAS), under contract with the International City/County Management Association (ICMA). The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of ICMA. 1 ASSESSMENT OF THE VULNERABILITIES AND LOCAL CAPACITIES OF CITIES DEVELOPMENT INITIATIVE (CDI) CITIES FOR BUILDING URBAN RESILIENCE Strengthening Urban Resilience for Growth with Equity (SURGE) Project CONTRACT NO. AID-492-H-15-00001 Program Title: USAID/SURGE Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID/Philippines Contract Number: AID-492-H-15-00001 Contractor: International City/County Management Association (ICMA) Date of Publication: December 23, 2016 USAID Strengthening Urban Resilience for Growth with Equity (SURGE) Project Page ii Assessment of the Vulnerabilities and Local Capacities of Cities Development Initiative (CDI) Cities for Building Urban Resilience USAID Strengthening Urban Resilience for Growth with Equity (SURGE) Project Page iii Assessment of the Vulnerabilities and Local Capacities of Cities Development Initiative (CDI) Cities for Building Urban -

Legazpi City: Disaster Response and Resiliency Initiatives

LEGAZPI CITY: DISASTER RESPONSE AND RESILIENCY INITIATIVES GILBERT C. GONZALES Regional Director DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL RESOURCES Philippines 6TH HIGH LEVEL SEMINAR ON ENVIRONMENTALLY SUSTAINABLE CITIES JOHOR BAHRU, MALAYSIA FEBRUARY 9-10, 2015 OUTLINE OF PRESENTATION 1. LEGAZPI CITY 2. ESC MODEL CITY: PHILIPPINE FRAMEWORK 3. CITYLINKS: LEGAZPI AND FT. LAUDERDALE 4. CLIMATE CHANGE RESILIENCY 5. ESC FORUM 6. OTHER ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT INITIATIVES I. LEGAZPI CITY: LOCATION MAP LEGAZPI CITY • Coastal city with frequent problems with natural disasters but keen to improve its resiliency to adapt to climate change • Situated on the eastern of Albay province approximately 534 kilometers south of Manila (Philippine capital) and centrally located in the Bicol Region. • Total Area: 20,437.09 Has • Population : approx. 210, 615 ( as of 2013 based on National Statistics Office • Barangays: 70 (45 are located in the Urban Area and the rest are distributed in the Rural Area) DISASTER RISK AND VULNERABILITY OF LEGAZPI CITY/ALBAY 19 to 21 typhoons per year in the Philippines with 3-5 major direct hits on Albay. About 198,000 houses threatened by wind destructions and at least 350,000 people have to evacuate. Mayon Volcano Eruption threatens 3 cities and 5 municipalities 127 villages or 11,000 to 12,000 families threatened by landslides About 300,000 population out of 1.2M threatened by tsunami Eight municipalities and two cities threatened by floods. 5 II. PHILIPPINE ESC MODEL CITIES I. YEAR1 1. PALO, LEYTE: SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT 2. PUERTO PRINCESA CITY: SWM 3. LEGAZPI CITY: CLIMATE CHANGE ADAPTATION AND DISASTER RISK RESPONSE II. -

The Project for Capacity Development on Transportation Planning and Database Management in the Republic of the Philippines

Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Department of Transportation and Communications (DOTC) The Project for Capacity Development on Transportation Planning and Database Management in the Republic of the Philippines MMUTIS Update and Enhancement Project (MUCEP) Manual vol. 3 Urban Transportation Planning December 2015 ALMEC Corporation Oriental Consultants Global Co., Ltd PREFACE The acceleration of economic activities and population concentration in Metro Manila and other cities in the Philippines has caused severe social problems such as traffic congestion, traffic accidents, and deterioration of the living environment. The development of the public transportation network is crucial in tackling these problems. In addition, investment in infrastructure development is essential to realize a sustainable economic growth. Metro Manila, in particular, requires a transportation policy to facilitate a modal shift from private cars to public transportation by developing and integrating transportation networks and strengthening linkages between transportation modes. It is within this context that the Government of Japan has provided technical assistance to the Philippines’ Department of Transportation and Communications (DOTC) and other related agencies through the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) in conducting a capacity development project entitled “The Project for Capacity Development on Transportation Planning and Database Management in the Republic of the Philippines.” MUCEP, as the project is known (short for MMUTIS Update and Capacity Enhancement Project), has been carried out for more than four years, starting on 27 September 2011 and completing on 30 November 2015. The overall project goal of MUCEP is to enable the DOTC to prepare a public transportation plan for Metro Manila for strategic corridors by strengthening their capacity in transportation database management and public transportation network planning.