This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020 1 REGA PLANAR 3 TURNTABLE. A Rega Planar 3 8 ASSORTED INDIE/PUNK MEMORABILIA. turntable with Pro-Ject Phono box. £200.00 - Approximately 140 items to include: a Morrissey £300.00 Suedehead cassette tape (TCPOP 1618), a ticket 2 TECHNICS. Five items to include a Technics for Joe Strummer & Mescaleros at M.E.N. in Graphic Equalizer SH-8038, a Technics Stereo 2000, The Beta Band The Three E.P.'s set of 3 Cassette Deck RS-BX707, a Technics CD Player symbol window stickers, Lou Reed Fan Club SL-PG500A CD Player, a Columbia phonograph promotional sticker, Rock 'N' Roll Comics: R.E.M., player and a Sharp CP-304 speaker. £50.00 - Freak Brothers comic, a Mercenary Skank 1982 £80.00 A4 poster, a set of Kevin Cummins Archive 1: Liverpool postcards, some promo photographs to 3 ROKSAN XERXES TURNTABLE. A Roksan include: The Wedding Present, Teenage Fanclub, Xerxes turntable with Artemis tonearm. Includes The Grids, Flaming Lips, Lemonheads, all composite parts as issued, in original Therapy?The Wildhearts, The Playn Jayn, Ween, packaging and box. £500.00 - £800.00 72 repro Stone Roses/Inspiral Carpets 4 TECHNICS SU-8099K. A Technics Stereo photographs, a Global Underground promo pack Integrated Amplifier with cables. From the (luggage tag, sweets, soap, keyring bottle opener collection of former 10CC manager and music etc.), a Michael Jackson standee, a Universal industry veteran Ric Dixon - this is possibly a Studios Bates Motel promo shower cap, a prototype or one off model, with no information on Radiohead 'Meeting People Is Easy 10 Min Clip this specific serial number available. -

иÑÐлбуð¼

Ð¥Ð¾Ð»Ð¸Ñ ÐÐ »Ð±ÑƒÐ¼ ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (Ð ´Ð¸ÑÐ ºÐ¾Ð³Ñ€Ð°Ñ„иÑÑ ‚а & график) Butterfly https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/butterfly-518974/songs Hollies Sing Dylan https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/hollies-sing-dylan-2081061/songs Would You Believe? https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/would-you-believe%3F-576533/songs Confessions of the Mind https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/confessions-of-the-mind-2992460/songs Distant Light https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/distant-light-3030708/songs Write On https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/write-on-8038412/songs Hollies Sing Hollies https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/hollies-sing-hollies-3139369/songs In The Hollies Style https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/in-the-hollies-style-1931072/songs Another Night https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/another-night-2852363/songs Romany https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/romany-3441132/songs Russian Roulette https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/russian-roulette-7382118/songs A Crazy Steal https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/a-crazy-steal-4656171/songs Hollies' Greatest https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/hollies%27-greatest-5881387/songs Here I Go Again https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/here-i-go-again-5737334/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-hollies%27-greatest-hits- The Hollies' Greatest Hits 16844238/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-hollies%27-greatest-hits- The Hollies' Greatest Hits 7739955/songs -

The Hollies Stop.Stop.Stop Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Hollies Stop.Stop.Stop mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Pop Album: Stop.Stop.Stop Country: Netherlands Released: 1979 Style: Pop Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1621 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1536 mb WMA version RAR size: 1989 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 489 Other Formats: MOD AUD AAC MIDI MP4 WAV TTA Tracklist A1 What's Wrong With The Way I Live A2 Pay You Back With Interest A3 Tell Me To My Face A4 Clown A5 Suspicious Look In Your Eyes A6 It's You B1 High Classed B2 Peculiar Situation B3 What Went Wrong B4 Crusader B5 Don't Even Think About Changing B6 Stop! Stop! Stop Credits Directed By [Accompaniment Directed By] – Mike Vickers (tracks: B1, B3, B4) Photography By – Henry Diltz Producer – Ron Richards Written-By – Clarke-Hicks-Nash Notes Stemra Super Sound (EMI) Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout: 51759-A-2 Matrix / Runout: 51759-B-2 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year For Certain Because... (LP, PMC 7011 The Hollies Parlophone PMC 7011 UK 1966 Album, Mono) Stop! Stop! Stop! (LP, Album, LP-9339 The Hollies Imperial LP-9339 US 1967 Mono) For Certain Because... (LP, PMC 7011 The Hollies Parlophone PMC 7011 India 1966 Album, Mono) For Certain Because... (LP, XEX 618 The Hollies Odeon XEX 618 Spain 1967 Album) For Certain Because... (LP, MT-1057 The Hollies Odeon MT-1057 Venezuela 1966 Album, Mono) Related Music albums to Stop.Stop.Stop by The Hollies The Hollies - For Certain Because... The Hollies - Stop In The Name Of Love The Hollies - Bus Stop / Don't Run And Hide The Hollies - 1963-1966 Hollies, The - Stop In The Name Of Love The Hollies - Stop! Stop! Stop! The Hollies - The Best Of The Hollies The Hollies - Stop Stop Stop / It's You The Hollies - Original Album Series The Hollies - Hollies' Greatest The Hollies - Evolution The Hollies - Bus Stop. -

The History of Rock Music: 1955-1966

The History of Rock Music: 1955-1966 Genres and musicians of the beginnings History of Rock Music | 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-75 | 1976-89 | The early 1990s | The late 1990s | The 2000s | Alpha index Musicians of 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-76 | 1977-89 | 1990s in the US | 1990s outside the US | 2000s Back to the main Music page Inquire about purchasing the book (Copyright © 2009 Piero Scaruffi) The Flood 1964-1965 (These are excerpts from my book "A History of Rock and Dance Music") The Tunesmiths TM, ®, Copyright © 2005 Piero Scaruffi All rights reserved. The Beach Boys' idea of wedding the rhythm of rock'n'roll and the melodies of pop music was taken to its logical conclusion in Britain by the bands of the so- called "Mersey Sound". The most famous of them, the Beatles, became the object of the second great swindle of rock'n'roll. In 1963 "Beatlemania" hit Britain, and in 1964 it spread through the USA. They became even more famous than Presley, and sold records in quantities that had never been dreamed of before them. Presley had proven that there was a market for rock'n'roll in the USA. Countless imitators proved that a similar market also existed in Europe, but they had to twist and reshape the sound and the lyrics. Britain had a tradition of importing forgotten bluesmen from the USA, and became the center of the European recording industry. European rock'n'roll was less interested in innuendos, more interested in dancing, and obliged to merge with the strong pop tradition. -

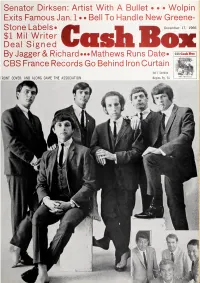

Deal Signed by Jagger& Richard •••Mathews Runs Date* CBS France Records Go Behind Iron Curtain

Senator Dirksen: Artist With A Bullet • • • Wolpin Exits Famous Jan. 1 • • Bell To Handle New Greene- Stone Labels* $1 Mil Writer Deal Signed By Jagger& Richard •••Mathews Runs Date* CBS France Records Go Behind Iron Curtain Int'l Section FRONT COVER: AND ALONG CAME THE ASSOCIATION Begins Pg. 55 p All the dimensions of a#l smash! *smm 1 4-439071 P&ul Revere am The THE single of '66 B THE SPIRIT OP *67 from this brand PAUL REVERE tiIe RAIDERS INCLUDING: HUNGRY THE GREAT AIRPLANE new album— STRIKE GOOD THING LOUISE 1001 ARABIAN NIGHTS CL2595/CS9395 (Stereo) Where the good things are. On COLUMBIA RECORDS ® "COLUMBIA ^MAPCAS REG PRINTED IN U SA GashBim Cash Bock Vol. XXVIII—Number 22 December 17, 1966 (Publication Office) 1780 Broadway New York, N. Y. 10019 (Phone: JUdson 6-2640) CABLE ADDRESS: CASHBOX, N. Y. JOE ORLECK Chairman of the Board GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher NORMAN ORLECK Executive Vice President MARTY OSTROW Vice President LEON SCHUSTER Disk Industry—1966 Treasurer IRV LICHTMAN Editor in Chief EDITORIAL TOM McENTEE Associate Editor RICK BOLSOM ALLAN DALE EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS MIKE MARTUCCI JERRY ORLECK BERNIE BLAKE The past few issues of Cash Box Speaking of deals, 1966 was marked Director Advertising of have told the major story of 1966. by a continuing merger of various in- ^CCOUNT EXECUTIVES While there were other developments dustry factors, not merely on a hori- STAN SO I PER BILL STUPER of considerable importance when the zontal level (label purchases of labels), Hollywood HARVEY GELLER, long-range view is taken into account, but vertical as well (ABC's purchase of ED ADLUM the record business is still a business a wholesaler, New Deal). -

November 1990

FEATURES INSIDE COLLARLOCK In an almost silent way, Mark Gauthier of Collarlock has been BOBBY a major contributor to the recent drum rack revolution. In ELLIOTT this special industry profile, Gauthier explains the nuts and LA. STUDIO Not too many bands have bolts (and much more) of build- remained together—and suc- ing the unique ROUND TABLE cessful—as long as the Hollies. Collarlock system. Bobby Elliott's drumming has • by Rick Van Horn been an integral part of the 30 Colaiuta, Keltner, Porcaro, Mason, Baird, Fongheiser, and band's sound since they began Schaeffer—seven of the most recording. Find out why drum- respected and requested drum- mers like Phil Collins and Cozy mers recording today. Put 'em Powell understand the value of in a room together and press Elliott's contributions to the the record button, and what Hollies' timeless MD TRIVIA have you got? Read music. on...and LEARN. •by Simon Goodwin 26 CONTEST • by Robyn Flans 18 Win a set of Paiste Sound Formula Cymbals! 64 Cover Photo: Lissa Wales COLUMNS Education 56 ROCK PERSPECTIVES The Benefits Of A Four-Piece Kit Equipment BY ANDY NEWMARK 36 PRODUCT 66 ROCK 'N' CLOSE-UP Departments JAZZ CLINIC Corder Celebrity Applying Cross Drumkit News Rhythms To The 4 EDITOR'S Drumset Part 2 BY RICK VAN HORN OVERVIEW UPDATE BY ROD MORGENSTEIN 8 38 Remo Legacy Michael Hodges, Drumheads 6 READERS' Marillion's Ian Mosley, 68 THE MACHINE BY RICK MATTINGLY PLATFORM Jerry Fehily of SHOP Hothouse Flowers, Drum Machines 40 Vic Firth Signature Bobby Z, plus News A To Z Drumsticks 12 ASK A PRO BY RIC FURLEY BY RICK MATTINGLY 14 IT'S Profiles STRICTLY 42 Nady SongStarter QUESTIONABLE 74 BY ADAM BUDOFSKY PORTRAITS TECHNIQUE 58 Rhythmic Rudimental IMPAC Snare 124 DRUM MARKET Dom Um Romao Progressions: Part 6 Replacement BY FRANK COLON BY JOE MORELLO BY WILLIAM F. -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

The Annotated Pratchett File, V7a.5

The Annotated Pratchett File, v7a.5 Collected and edited by: Leo Breebaart <[email protected]> Assistant Editor: Mike Kew <[email protected]> Organisation: Unseen University Newsgroups: alt.fan.pratchett,alt.books.pratchett Archive name: apf–7a.5.3.5 Last modified: 25 July 2002 Version number: 7a.5.3.5 Contents 1 Preface to v7a.5 5 2 Introduction 7 3 Editorial Comments for v7a.5 9 PAGE NUMBERS . 9 OTHER ANNOTATIONS . 10 4 Discworld Annotations 11 THE COLOUR OF MAGIC . 11 THE LIGHT FANTASTIC . 22 EQUAL RITES . 28 MORT.................................... 32 SOURCERY . 39 WYRD SISTERS . 48 PYRAMIDS . 59 GUARDS! GUARDS! . 71 ERIC . 79 MOVING PICTURES . 84 REAPER MAN . 94 WITCHES ABROAD . 106 SMALL GODS . 118 LORDS AND LADIES . 132 MEN AT ARMS . 148 SOUL MUSIC . 164 INTERESTING TIMES . 187 2 APF v7a.5.3.4, April 2002 MASKERADE . 193 FEET OF CLAY . 199 HOGFATHER . 215 JINGO . 231 THE LAST CONTINENT . 244 CARPE JUGULUM . 258 THE FIFTH ELEPHANT . 271 THE TRUTH . 271 THIEF OF TIME . 271 THE LAST HERO . 271 THE AMAZING MAURICE AND HIS EDUCATED RODENTS . 272 NIGHT WATCH . 272 THE WEE FREE MEN . 272 THE 2003 DISCWORLD NOVEL . 272 THE 2004 DISCWORLD NOVEL . 273 THE DISCWORLD COMPANION . 273 THE SCIENCE OF DISCWORLD . 276 THE SCIENCE OF DISCWORLD II: THE GLOBE . 276 THE STREETS OF ANKH-MORPORK . 276 THE DISCWORLD MAPP . 276 A TOURIST GUIDE TO LANCRE . 276 DEATH’S DOMAIN . 277 5 Other Annotations 279 GOOD OMENS . 279 STRATA . 295 THE DARK SIDE OF THE SUN . 296 TRUCKERS . 298 DIGGERS . 300 WINGS . 301 ONLY YOU CAN SAVE MANKIND . 302 JOHNNY AND THE DEAD . -

Artist / Bandnavn Album Tittel Utg.År Label/ Katal.Nr

ARTIST / BANDNAVN ALBUM TITTEL UTG.ÅR LABEL/ KATAL.NR. LAND LP KOMMENTAR A 80-talls synthpop/new wave. Fikk flere hitsingler fra denne skiva, bl.a The look of ABC THE LEXICON OF LOVE 1983 VERTIGO 6359 099 GER LP love, Tears are not enough, All of my heart. Mick fra den første utgaven av Jethro Tull og Blodwyn Pig med sitt soloalbum fra ABRAHAMS, MICK MICK ABRAHAMS 1971 A&M RECORDS SP 4312 USA LP 1971. Drivende god blues / prog rock. Min første og eneste skive med det tyske heavy metal bandet. Et absolutt godt ACCEPT RESTLESS AND WILD 1982 BRAIN 0060.513 GER LP album, med Udo Dirkschneider på hylende vokal. Fikk opplevd Udo og sitt band live på Byscenen i Trondheim november 2017. Meget overraskende og positiv opplevelse, med knallsterke gitarister, og sønnen til Udo på trommer. AC/DC HIGH VOLTAGE 1975 ATL 50257 GER LP Debuten til hardrocker'ne fra Down Under. AC/DC POWERAGE 1978 ATL 50483 GER LP 6.albumet i rekken av mange utgivelser. ACKLES, DAVID AMERICAN GOTHIC 1972 EKS-75032 USA LP Strålende låtskriver, albumet produsert av Bernie Taupin, kompisen til Elton John. HEADLINES AND DEADLINES – THE HITS WARNER BROS. A-HA 1991 EUR LP OF A-HA RECORDS 7599-26773-1 Samlealbum fra de norske gutta, med låter fra perioden 1985-1991 AKKERMAN, JAN PROFILE 1972 HARVEST SHSP 4026 UK LP Soloalbum fra den glimrende gitaristen fra nederlandske progbandet Focus. Akkermann med klassisk gitar, lutt og et stor orkester til hjelp. I tillegg rockere som AKKERMAN, JAN TABERNAKEL 1973 ATCO SD 7032 USA LP Tim Bogert bass og Carmine Appice trommer. -

The Hollies Éÿ³æ¨‚Å°ˆè¼¯ ĸ²È¡Œ (ĸ“Ⱦ‘ & Æ—¶É—´È¡¨)

The Hollies 音樂專輯 串行 (专辑 & 时间表) Butterfly https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/butterfly-518974/songs Hollies Sing Dylan https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/hollies-sing-dylan-2081061/songs Would You Believe? https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/would-you-believe%3F-576533/songs Confessions of the Mind https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/confessions-of-the-mind-2992460/songs Distant Light https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/distant-light-3030708/songs Write On https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/write-on-8038412/songs Hollies Sing Hollies https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/hollies-sing-hollies-3139369/songs In The Hollies Style https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/in-the-hollies-style-1931072/songs Another Night https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/another-night-2852363/songs Romany https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/romany-3441132/songs Russian Roulette https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/russian-roulette-7382118/songs A Crazy Steal https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/a-crazy-steal-4656171/songs Hollies' Greatest https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/hollies%27-greatest-5881387/songs Here I Go Again https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/here-i-go-again-5737334/songs https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-hollies%27-greatest-hits- The Hollies' Greatest Hits 16844238/songs https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-hollies%27-greatest-hits- The Hollies' Greatest Hits 7739955/songs https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/dear-eloise-%2F-king-midas-in-reverse- -

Freewheelin 195 Contents

freewheelin-on-line take four Freewheelin’ 202 June 2002 We are not the only ones who are forging ahead with an exciting new concept involving the use of the internet. The BBC in conjunction with the National Gallery have set up the first – only online- major art show exhibiting 100 ‘weather’ paintings taken from 50 UK galleries and museums. The exhibition, which has the title‘Painting The Weather’ can be found at www.bbc.co.uk/paintingtheweather and if you visit this wonderful site you will be able to marvel at the works of many artists who have used the weather as a symbol in the expression of their art. Following this theme, ‘the weather’ just happens to be central to this month’s Freewheelin’ cover. And as we are in the midst of an English summer, we have to be talking stormy weather. The framed backdrop is a painting taken from the aforesaid ‘net exhibition and is by that great painter of English weather J.M.W. Turner (1775- 1851). In the foreground, the pvc weather-proofs are modelled by Bob and Sara which is quite apt because a (wicked?) messenger sent him to her in a tropical storm in the first place. The distance between them on such a wet day suggests that he may have already looked elsewhere for some shelter from the storm. Bob’s eyes and the eye of the storm are dark and parallel and to this day I am truly not sure if it was Turner’s lashing rain or Dylan’s blinding tears that soaked my page and caused my letters to run. -

Beatles Venezuelan LP's, Identification Guide

Venezuelan LP Releases Identification Guide Last Updated 25 De 18 Rainbow Odeon Label Venezuela would have to wait until the end of 1963 before they could hear an album of Beatles songs. When the Beatles released that first LP through Odeon, the label was using a colorful "rainbow" design, a popular backdrop that remained through the end of 1965. These early albums were released in mono only. LP's originally released on this label style Catalog Number Estos Son Los Beatles (With the Beatles) OLP 371 Surfing con Los Beatles en Accion OLP 382 Yeah Yeah Yeah (A Hard Day's Night) OLP 409 Beatles Hits OLP 416 Beatles '65 OLP 447 Help! (cover has US album graphics) OLP 474 Rubber Soul OLP 509 NOTE 1: The Surfing LP is a unique compilation, featuring... Side 1, "Can't Buy Me Love"; "You Can't Do That"; "Ask Me Why"; "A Taste of Honey"; "Do You Want to Know a Secret"; "Please, Please Me"; Side 2, "I Want to Hold Your Hand"; "She Loves You"; "I'll Get You"; "Thank You Girl"; "From Me to You"; and "Twist and Shout." NOTE 2: The Hits LP is a unique compilation, containing... Side 1, "Chains"; "Things We Said Today"; "Any Time at All"; "When I Get Home"; Please, Please Me"; "Slow Down"; Side 2, "Tell Me Why"; "Misery"; "Boys"; "There's a Place"; "Anna"; "I Wanna Be Your Man"; and "Komm, Gib Mir Deine Hand." NOTE 3: The '65 LP is also unique, featuring... Side 1, "She's a Woman"; "I'll be Back"; "I'm a Loser"; "Rock and Roll Music"; "Baby's in Black"; "What You're Doing"; Side 2, "Honey, Don't"; "Mr.