Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

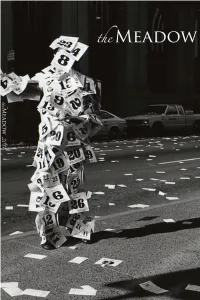

The Meadow 2011 Literary and Art Journal

MEADOW the 2011 TRUCKEE MEADOWS COMMUNITY COLLEGE Reno, Nevada The Meadow is the annual literary arts journal published ev- Editor-in-Chief ery spring by Truckee Meadows Community College in Reno, Lindsay Wilson Nevada. Students interested in the literary arts, graphic design, and creative writing are encouraged to participate on Poetry Editors the Editorial Board. Visit www.tmcc.edu/meadow for infor- Erika Bein mation and submission guidelines. Look for notices around Joe Hunt campus, in The Echo student newspaper, or contact the Editor-in-Chief at [email protected] or through the English Fiction Editor department at (775) 673-7092. Mark Maynard See our website (listed above) for information on our annual Non-Fiction Editor Cover Design and Literary and Art Contests. Only TMCC Rob Lively students are eligible for prizes. Editorial Board At this time, The Meadow is not interested in acquiring rights David Anderson to contributors’ works. All rights revert to the author or art- Melissa Cosgrove ist upon publication, and we expect The Meadow to be ac- knowledged as original publisher in any future chapbooks or Andrew Crimmins books. John Dodge JoAnn Hoskins The Meadow is indexed in The International Directory of Little Theodore Hunt Magazines and Small Presses. Janice Huntoon Our address is Editor-in-Chief, The Meadow, Truckee Mead- Arian Katsimbras ows Community College, English Department, Vista B300, Rachel Meyer 7000 Dandini Blvd., Reno, Nevada 89512. Peter Nygard The views expressed in The Meadow are solely reflective of Tony Olsen the authors’ perspectives. TMCC takes no responsibility for Drew Pearson the creative expression contained herein. -

Pieces of a Woman

PIECES OF A WOMAN Directed by Kornél Mundruczó Starring Vanessa Kirby, Shia LaBeouf, Molly Parker, Sarah Snook, Iliza Shlesinger, Benny Safdie, Jimmie Falls, Ellen Burstyn **WORLD PREMIERE – In Competition – Venice Film Festival 2020** **OFFICIAL SELECTION – Gala Presentations – Toronto International Film Festival 2020** Press Contacts: US: Julie Chappell | [email protected] International: Claudia Tomassini | [email protected] Sales Contact: Linda Jin | [email protected] 1 SHORT SYNOPSIS When an unfathomable tragedy befalls a young mother (Vanessa Kirby), she begins a year-long odyssey of mourning that touches her husband (Shia LaBeouf), her mother (Ellen Burstyn), and her midwife (Molly Parker). Director Kornél Mundruczó (White God, winner of the Prix Un Certain Regard Award, 2014) and partner/screenwriter Kata Wéber craft a deeply personal meditation and ultimately transcendent story of a woman learning to live alongside her loss. SYNOPSIS Martha and Sean Carson (Vanessa Kirby, Shia LaBeouf) are a Boston couple on the verge of parenthood whose lives change irrevocably during a home birth at the hands of a flustered midwife (Molly Parker), who faces charges of criminal negligence. Thus begins a year-long odyssey for Martha, who must navigate her grief while working through fractious relationships with her husband and her domineering mother (Ellen Burstyn), along with the publicly vilified midwife whom she must face in court. From director Kornél Mundruczó (White God, winner of the Prix Un Certain Regard Award, 2014), with artistic support from executive producer Martin Scorsese, and written by Kata Wéber, Mundruczó’s partner, comes a deeply personal, searing domestic aria in exquisite shades of grey and an ultimately transcendent story of a woman learning to live alongside her loss. -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

Mary in Film

PONT~CALFACULTYOFTHEOLOGY "MARIANUM" INTERNATIONAL MARIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE (UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON) MARY IN FILM AN ANALYSIS OF CINEMATIC PRESENTATIONS OF THE VIRGIN MARY FROM 1897- 1999: A THEOLOGICAL APPRAISAL OF A SOCIO-CULTURAL REALITY A thesis submitted to The International Marian Research Institute In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree Licentiate of Sacred Theology (with Specialization in Mariology) By: Michael P. Durley Director: Rev. Johann G. Roten, S.M. IMRI Dayton, Ohio (USA) 45469-1390 2000 Table of Contents I) Purpose and Method 4-7 ll) Review of Literature on 'Mary in Film'- Stlltus Quaestionis 8-25 lli) Catholic Teaching on the Instruments of Social Communication Overview 26-28 Vigilanti Cura (1936) 29-32 Miranda Prorsus (1957) 33-35 Inter Miri.fica (1963) 36-40 Communio et Progressio (1971) 41-48 Aetatis Novae (1992) 49-52 Summary 53-54 IV) General Review of Trends in Film History and Mary's Place Therein Introduction 55-56 Actuality Films (1895-1915) 57 Early 'Life of Christ' films (1898-1929) 58-61 Melodramas (1910-1930) 62-64 Fantasy Epics and the Golden Age ofHollywood (1930-1950) 65-67 Realistic Movements (1946-1959) 68-70 Various 'New Waves' (1959-1990) 71-75 Religious and Marian Revival (1985-Present) 76-78 V) Thematic Survey of Mary in Films Classification Criteria 79-84 Lectures 85-92 Filmographies of Marian Lectures Catechetical 93-94 Apparitions 95 Miscellaneous 96 Documentaries 97-106 Filmographies of Marian Documentaries Marian Art 107-108 Apparitions 109-112 Miscellaneous 113-115 Dramas -

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List # 20 Wild Westerns: Marshals & Gunman 2 Days in the Valley (2 Discs) 2 Family Movies: Family Time: Adventures 24 Season 1 (7 Discs) of Gallant Bess & The Pied Piper of 24 Season 2 (7 Discs) Hamelin 24 Season 3 (7 Discs) 3:10 to Yuma 24 Season 4 (7 Discs) 30 Minutes or Less 24 Season 5 (7 Discs) 300 24 Season 6 (7 Discs) 3-Way 24 Season 7 (6 Discs) 4 Cult Horror Movies (2 Discs) 24 Season 8 (6 Discs) 4 Film Favorites: The Matrix Collection- 24: Redemption 2 Discs (4 Discs) 27 Dresses 4 Movies With Soul 40 Year Old Virgin, The 400 Years of the Telescope 50 Icons of Comedy 5 Action Movies 150 Cartoon Classics (4 Discs) 5 Great Movies Rated G 1917 5th Wave, The 1961 U.S. Figure Skating Championships 6 Family Movies (2 Discs) 8 Family Movies (2 Discs) A 8 Mile A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2 Discs) 10 Bible Stories for the Whole Family A.R.C.H.I.E. 10 Minute Solution: Pilates Abandon 10 Movie Adventure Pack (2 Discs) Abduction 10,000 BC About Schmidt 102 Minutes That Changed America Abraham Lincoln Vampire Hunter 10th Kingdom, The (3 Discs) Absolute Power 11:14 Accountant, The 12 Angry Men Act of Valor 12 Years a Slave Action Films (2 Discs) 13 Ghosts of Scooby-Doo, The: The Action Pack Volume 6 complete series (2 Discs) Addams Family, The 13 Hours Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ Smarter 13 Towns of Huron County, The: A 150 Year Brother, The Heritage Adventures in Babysitting 16 Blocks Adventures in Zambezia 17th Annual Lane Automotive Car Show Adventures of Dally & Spanky 2005 Adventures of Elmo in Grouchland, The 20 Movie Star Films Adventures of Huck Finn, The Hartford Public Library DVD Title List Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. -

Preacher's Magazine Volume 67 Number 04 Randal E

Olivet Nazarene University Digital Commons @ Olivet Preacher's Magazine Church of the Nazarene 6-1-1992 Preacher's Magazine Volume 67 Number 04 Randal E. Denny (Editor) Olivet Nazarene University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/cotn_pm Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, International and Intercultural Communication Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, and the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Denny, Randal E. (Editor), "Preacher's Magazine Volume 67 Number 04" (1992). Preacher's Magazine. 602. https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/cotn_pm/602 This Journal Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Church of the Nazarene at Digital Commons @ Olivet. It has been accepted for inclusion in Preacher's Magazine by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Olivet. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Year of Preaching BRINGING THE WORD INTO THE WORLD PREACHING TO WOMEN CULTIVATING THE FINE ART OF STORY PREACHING THE THREE MOST COMMON MISTAKES EVEN GOOD PREACHERS MAKE o Godlet me preach with enthusiasm because of what Christ didnot because of what the crowds think; because of the salvation we have, not the size of the group we have. Use m e O God!, not because it's the hour for the message, but because You’ve given me a message for the hour. —Ed Towne SUITABLE FOR FRAMING y EDITORIAL Preaching— Putting Light into People's Faces by Randal E. Denny Spokane, Wash. hen Edward Rosenow was God. Pastors can do nothing with you will be left adrift on a glassy sea, a small boy, his brother more direct and eternal results than with no wind of the Spirit to carry became seriously ill. -

Catalogue 2012 Main Index 2012

CATALOGUE 2012 MAIN INDEX 2012 Welcome 3 Fiction 5 Feature Films 6 Short Films 98 TV Movies 160 Series 174 New Platforms 185 Documentary 189 Feature Films 190 Short Films 226 Television Documentaries 251 Animation 301 Feature Films 302 Short Films 310 Series 318 New Platforms 345 Videogames 353 Others 369 Sales & Production Companies 373 Title Index 395 Catalan Language Production c Steadfast in our commitment to supporting the Catalan audiovisual industry and in keeping with our annual date, we are delighted to present you with the latest edition of the Catalan Films & TV catalogue, a publication that is now time-honoured (it’s been 26 years!!!!) and recognised as an international benchmark, featuring the collection of titles of both this season and the forthcoming one. This year’s catalogue includes more than 400 works produced either entirely by Catalan producers or co-produced with other regions in Spain and abroad, covering themes and styles that range from comedy to drama, along with the genre films that have given us an excellent position in international markets in recent years. Not to be forgotten, of course, are the documentary and TV animation, both of which continue to boast a prominent niche of their own in the industry. This catalogue is one of the key tools that enable Catalan Films & TV to take part in the leading international audiovisual markets and festivals on the 2012 agenda, which has been approved by participating CF&TV members. Indeed, despite the circumstances of the world economy, the Catalan audiovisual industry is in excellent health. Pa Negre / Black Bread, for example, was the Spanish Film Academy’s proposed candidate in the race to the 2012 Oscars. -

UC San Francisco Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCSF UC San Francisco Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Jailcare: The Safety Net of a U.S. Women's Jail Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/88w6d295 Author Sufrin, Carolyn Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Jailcare: The Safely Net of a U.S. Women's Jail by Carolyn B, Sufrin DISSERTATION Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Medical Anthropology in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the ii for my parents. iii ABSTRACT Institutions of incarceration are widely understood for their punitive, depriving, and at times even violent characteristics. Yet prisons and jails also provide medical care and other services that people marginalized by poverty, addiction, racism, and other forces of structural inequality might not otherwise have. This dissertation investigates the everyday contours of care in an urban women’s jail in California. Based on six years of clinical work as an Ob/Gyn in the jail’s clinic; ethnographic fieldwork throughout the jail and its surrounding community; and over 40 interviews with jail workers, medical staff and inmates, I describe how this jail was constituted by caregiving relationships which were inextricably linked to disciplinary structures, particularly for pregnant women. Deficiencies in the public safety net, market shifts, and trenchant problems in the criminal justice system meant that cycling between jail and the streets was a normative rhythm of everyday life for many of the urban poor. Recidivism was less a statistic and more an intimate relationship between inmates and jail workers. -

Great Bellies and Boy Actors: Pregnancy Plays on the Stuart Stage, 1603-1642

GREAT BELLIES AND BOY ACTORS: PREGNANCY PLAYS ON THE STUART STAGE, 1603-1642 BY SARA B.T. THIEL DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theatre with a minor in Gender and Women’s Studies in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2017 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Andrea Stevens, Co-Chair Associate Professor Valleri Robinson, Co-Chair Associate Professor Catharine Gray Course Director Mardia J. Bishop “Great Bellies and Boy Actors: Pregnancy Plays on the Stuart Stage, 1603-1642” Abstract Before 1603, pregnant characters were seldom present on English stages; because of mounting anxiety over Elizabeth’s failure to produce an heir, representations of pregnant bodies were, perhaps wisely, rare. In contrast, after James’s succession, dramatists displayed a growing interest in staging visibly pregnant characters that drive dramatic action, despite prevalent notions of the motherless Stuart stage. For example, Felicity Dunworth has suggested that the staged mother all but disappears upon James’s arrival to the throne. Despite scholarly biases toward maternal erasure on English stages after Elizabeth’s death, I argue the gestating body was indeed a site of dramatic interest, evinced by the wide variety of pregnancy plays written by the period’s most prolific writers including Shakespeare, Jonson, Middleton, and Heywood, to name a few. In “Great Bellies and Boy Actors,” I analyze all twenty-two extant—what I term—“pregnancy plays,” first performed between 1603 and 1642. The defining characteristic of this dramatic subgenre is a pregnancy or pregnant character that drives the action of a plot in some significant way. -

Public Transportation, Material Differences, and the Power of Mobile Communities in Chicago

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2014 Moving Social Spaces: Public Transportation, Material Differences, and the Power of Mobile Communities in Chicago Gwendolyn Purifoye Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Purifoye, Gwendolyn, "Moving Social Spaces: Public Transportation, Material Differences, and the Power of Mobile Communities in Chicago" (2014). Dissertations. 1298. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/1298 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2014 Gwendolyn Purifoye LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO MOVING SOCIAL SPACES: PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION, MATERIAL DIFFERENCES, AND THE POWER OF MOBILE COMMUNITIES IN CHICAGO A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN SOCIOLOGY BY GWENDOLYN Y. PURIFOYE CHICAGO, IL AUGUST 2014 Copyright by Gwendolyn Y. Purifoye, 2014 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Successful completion of this dissertation project would have not been possible without the continual support of family, my church, friends, colleagues, and my committee. I would like to thank these many outstanding people beginning with my very wonderful, beautiful, selfless, and loving mother, Earnestine Burton. My mother has been my rock my entire life and I can never repay her for moving in with me as I began this project and for supporting me emotionally, spiritually, and in the special ways that only a mother can. -

I We Once Lived in Caves and Other Stories by Khristian Mecom A

We Once Lived in Caves and Other Stories by Khristian Mecom A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of Degree of Master of Fine Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL May 2011 i We Once Lived in Caves and Other Stories by Khristian Mecom This thesis was prepared under the direction ofthe candidate's thesis advisor, A. Papatya Bucak, M.F.A., Department of English, and has been approved by the members of her supervisory committee. It was submitted to the faculty ofthe Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters and was accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree ofMaster ofFine Arts. SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: == Wenying Xu, Ph.D. ~~IChair, Department ofEnglish MajUIlaPeIldakUf]h.D. Dean, The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters kl151 UJ/J B!"T1o!~~- Date Dean, Graduate College 11 Acknowledgements The author would like to express her sincerest gratitude to her family, especially her mother and father, for all of their support and love, without who this collection of stories would not have been possible to write. Also, she would like to thank her thesis committee members, Professor Kate Schmitt and Professor Elena Machado. And a special thanks to Professor A. Papatya Bucak, her committee chair, who has been an instrumental guide and teacher, without who the author would not be able to call herself a ‘writer.’ iii Abstract Author: Khristian Mecom Title: We Once Lived in Caves and Other Stories Institution: Florida Atlantic University Thesis Advisor: A. -

Sickness Unto Death Derek Ayeh Reviews Atul Gawande’S Being Mortal 50

1839 The New Inquiry Magazine Vol. 35 | December 2014 Traité complet de l’anatomie de l’homme: comprenant la médicine opératoire, de l’homme: comprenant de l’anatomie complet Traité The New Inquiry Magazine is licensed under a creative commons license [cc-by-nc-nd 3.0] thenewinquiry.com Cover and following images: and following Cover Editor in Chief Ayesha Siddiqi Publisher Rachel Rosenfelt Creative Director Imp Kerr Executive Editor Rob Horning Senior Editor Max Fox Managing Editor Joseph Barkeley Editors Atossa Abrahamian Rahel Aima Aaron Bady Hannah Black Adrian Chen Emily Cooke Malcolm Harris Maryam Monalisa Gharavi Willie Osterweil Alix Rule Contributing Editors Alexander Benaim Nathan Jurgenson Sarah Leonard Sarah Nicole Prickett Special Projects Will Canine Angela Chen Samantha Garcia Natasha Lennard John McElwee Editors at Large Tim Barker Jesse Darling Elizabeth Greenwood Erwin Montgomery Laurie Penny Founding Editors Rachel Rosenfelt Jennifer Bernstein Mary Borkowski essays 8. Crazy in Love by Hannah Black 13. The Honeyed Siphon by Evan Calder Williams 22. Of Suicide by Natasha Lennard 26. Weight Gains by Willie Osterweil 31. Who Cares by Laura Anne Robertson 35. Circle Circle Dot Dot by Yahdon Israel 39. The Sororal Death by Anne Boyer 42. Taking Shit From Others by Janani Balasubramanian review 45. Sickness Unto Death Derek Ayeh reviews Atul Gawande’s Being Mortal 50. The Host in the Machine column Sara Black McCulloch reviews Eula Biss’s On Immunity 55. Dear Marooned Alien Princess by Zahira Kelly BEING sick changes your relation to your into such predictably lethal contact. The past hundred days body and how you inhabit it.