Sickness Unto Death Derek Ayeh Reviews Atul Gawande’S Being Mortal 50

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

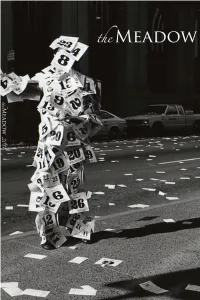

The Meadow 2011 Literary and Art Journal

MEADOW the 2011 TRUCKEE MEADOWS COMMUNITY COLLEGE Reno, Nevada The Meadow is the annual literary arts journal published ev- Editor-in-Chief ery spring by Truckee Meadows Community College in Reno, Lindsay Wilson Nevada. Students interested in the literary arts, graphic design, and creative writing are encouraged to participate on Poetry Editors the Editorial Board. Visit www.tmcc.edu/meadow for infor- Erika Bein mation and submission guidelines. Look for notices around Joe Hunt campus, in The Echo student newspaper, or contact the Editor-in-Chief at [email protected] or through the English Fiction Editor department at (775) 673-7092. Mark Maynard See our website (listed above) for information on our annual Non-Fiction Editor Cover Design and Literary and Art Contests. Only TMCC Rob Lively students are eligible for prizes. Editorial Board At this time, The Meadow is not interested in acquiring rights David Anderson to contributors’ works. All rights revert to the author or art- Melissa Cosgrove ist upon publication, and we expect The Meadow to be ac- knowledged as original publisher in any future chapbooks or Andrew Crimmins books. John Dodge JoAnn Hoskins The Meadow is indexed in The International Directory of Little Theodore Hunt Magazines and Small Presses. Janice Huntoon Our address is Editor-in-Chief, The Meadow, Truckee Mead- Arian Katsimbras ows Community College, English Department, Vista B300, Rachel Meyer 7000 Dandini Blvd., Reno, Nevada 89512. Peter Nygard The views expressed in The Meadow are solely reflective of Tony Olsen the authors’ perspectives. TMCC takes no responsibility for Drew Pearson the creative expression contained herein. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

Pieces of a Woman

PIECES OF A WOMAN Directed by Kornél Mundruczó Starring Vanessa Kirby, Shia LaBeouf, Molly Parker, Sarah Snook, Iliza Shlesinger, Benny Safdie, Jimmie Falls, Ellen Burstyn **WORLD PREMIERE – In Competition – Venice Film Festival 2020** **OFFICIAL SELECTION – Gala Presentations – Toronto International Film Festival 2020** Press Contacts: US: Julie Chappell | [email protected] International: Claudia Tomassini | [email protected] Sales Contact: Linda Jin | [email protected] 1 SHORT SYNOPSIS When an unfathomable tragedy befalls a young mother (Vanessa Kirby), she begins a year-long odyssey of mourning that touches her husband (Shia LaBeouf), her mother (Ellen Burstyn), and her midwife (Molly Parker). Director Kornél Mundruczó (White God, winner of the Prix Un Certain Regard Award, 2014) and partner/screenwriter Kata Wéber craft a deeply personal meditation and ultimately transcendent story of a woman learning to live alongside her loss. SYNOPSIS Martha and Sean Carson (Vanessa Kirby, Shia LaBeouf) are a Boston couple on the verge of parenthood whose lives change irrevocably during a home birth at the hands of a flustered midwife (Molly Parker), who faces charges of criminal negligence. Thus begins a year-long odyssey for Martha, who must navigate her grief while working through fractious relationships with her husband and her domineering mother (Ellen Burstyn), along with the publicly vilified midwife whom she must face in court. From director Kornél Mundruczó (White God, winner of the Prix Un Certain Regard Award, 2014), with artistic support from executive producer Martin Scorsese, and written by Kata Wéber, Mundruczó’s partner, comes a deeply personal, searing domestic aria in exquisite shades of grey and an ultimately transcendent story of a woman learning to live alongside her loss. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 NOTE TO USERS The original manuscript received by UMI contains pages with slanted print. Pages were microfilmed as received. This reproduction is the best copy available UMI WOMEN AND THE DYNAMIC INTERACTION OF TRADITIONAL AND CLINICAL MEDICINE ON THE BLACK SEA COAST OF TURKEY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Sylvia Wing Onder, M. -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

Copyright by Jessica Lyle Anaipakos 2012

Copyright by Jessica Lyle Anaipakos 2012 The Thesis Committee for Jessica Lyle Anaipakos Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Celebrity and Fandom on Twitter: Examining Electronic Dance Music in the Digital Age APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Shanti Kumar Janet Staiger Celebrity and Fandom on Twitter: Examining Electronic Dance Music in the Digital Age by Jessica Lyle Anaipakos, B.S. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin December 2012 Dedication To G&C and my twin. Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the guidance, encouragement, knowledge, patience, and positive energy of Dr. Shanti Kumar and Dr. Janet Staiger. I am sincerely appreciative that they agreed to take this journey with me. I would also like to give a massive shout out to the Radio-Television-Film Department. A big thanks to my friends Branden Whitehurst and Elvis Vereançe Burrows and another thank you to Bob Dixon from Seven Artist Management for allowing me to use Harper Smith’s photograph of Skrillex from Electric Daisy Carnival. v Abstract Celebrity and Fandom on Twitter: Examining Electronic Dance Music in the Digital Age Jessica Lyle Anaipakos, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2012 Supervisor: Shanti Kumar This thesis looks at electronic dance music (EDM) celebrity and fandom through the eyes of four producers on Twitter. Twitter was initially designed as a conversation platform, loosely based on the idea of instant-messaging but emerged in its current form as a micro-blog social network in 2009. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Mary in Film

PONT~CALFACULTYOFTHEOLOGY "MARIANUM" INTERNATIONAL MARIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE (UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON) MARY IN FILM AN ANALYSIS OF CINEMATIC PRESENTATIONS OF THE VIRGIN MARY FROM 1897- 1999: A THEOLOGICAL APPRAISAL OF A SOCIO-CULTURAL REALITY A thesis submitted to The International Marian Research Institute In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree Licentiate of Sacred Theology (with Specialization in Mariology) By: Michael P. Durley Director: Rev. Johann G. Roten, S.M. IMRI Dayton, Ohio (USA) 45469-1390 2000 Table of Contents I) Purpose and Method 4-7 ll) Review of Literature on 'Mary in Film'- Stlltus Quaestionis 8-25 lli) Catholic Teaching on the Instruments of Social Communication Overview 26-28 Vigilanti Cura (1936) 29-32 Miranda Prorsus (1957) 33-35 Inter Miri.fica (1963) 36-40 Communio et Progressio (1971) 41-48 Aetatis Novae (1992) 49-52 Summary 53-54 IV) General Review of Trends in Film History and Mary's Place Therein Introduction 55-56 Actuality Films (1895-1915) 57 Early 'Life of Christ' films (1898-1929) 58-61 Melodramas (1910-1930) 62-64 Fantasy Epics and the Golden Age ofHollywood (1930-1950) 65-67 Realistic Movements (1946-1959) 68-70 Various 'New Waves' (1959-1990) 71-75 Religious and Marian Revival (1985-Present) 76-78 V) Thematic Survey of Mary in Films Classification Criteria 79-84 Lectures 85-92 Filmographies of Marian Lectures Catechetical 93-94 Apparitions 95 Miscellaneous 96 Documentaries 97-106 Filmographies of Marian Documentaries Marian Art 107-108 Apparitions 109-112 Miscellaneous 113-115 Dramas -

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List # 20 Wild Westerns: Marshals & Gunman 2 Days in the Valley (2 Discs) 2 Family Movies: Family Time: Adventures 24 Season 1 (7 Discs) of Gallant Bess & The Pied Piper of 24 Season 2 (7 Discs) Hamelin 24 Season 3 (7 Discs) 3:10 to Yuma 24 Season 4 (7 Discs) 30 Minutes or Less 24 Season 5 (7 Discs) 300 24 Season 6 (7 Discs) 3-Way 24 Season 7 (6 Discs) 4 Cult Horror Movies (2 Discs) 24 Season 8 (6 Discs) 4 Film Favorites: The Matrix Collection- 24: Redemption 2 Discs (4 Discs) 27 Dresses 4 Movies With Soul 40 Year Old Virgin, The 400 Years of the Telescope 50 Icons of Comedy 5 Action Movies 150 Cartoon Classics (4 Discs) 5 Great Movies Rated G 1917 5th Wave, The 1961 U.S. Figure Skating Championships 6 Family Movies (2 Discs) 8 Family Movies (2 Discs) A 8 Mile A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2 Discs) 10 Bible Stories for the Whole Family A.R.C.H.I.E. 10 Minute Solution: Pilates Abandon 10 Movie Adventure Pack (2 Discs) Abduction 10,000 BC About Schmidt 102 Minutes That Changed America Abraham Lincoln Vampire Hunter 10th Kingdom, The (3 Discs) Absolute Power 11:14 Accountant, The 12 Angry Men Act of Valor 12 Years a Slave Action Films (2 Discs) 13 Ghosts of Scooby-Doo, The: The Action Pack Volume 6 complete series (2 Discs) Addams Family, The 13 Hours Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ Smarter 13 Towns of Huron County, The: A 150 Year Brother, The Heritage Adventures in Babysitting 16 Blocks Adventures in Zambezia 17th Annual Lane Automotive Car Show Adventures of Dally & Spanky 2005 Adventures of Elmo in Grouchland, The 20 Movie Star Films Adventures of Huck Finn, The Hartford Public Library DVD Title List Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. -

Artist Title Genre 10 Years Beautiful - No Lyrics - Pop 10Cc I'm Not in Love Rock 12 Stones Way I Fell, the - No Lyrics - Worship 1975, the Chocolate - No Lyrics - RM

Artist Title Genre 10 Years Beautiful - No Lyrics - Pop 10cc I'm Not In Love Rock 12 Stones Way I Fell, The - No Lyrics - Worship 1975, The Chocolate - No Lyrics - RM 2 Chainz & Wiz Khalifa We Own It (Fast & Furious) - No Lyrics - Rap 2 Chainz ftg. Drake & Lil Wayne I Do It - No Lyrics - Rap 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun Pop 3 Doors Down Better Life, The Pop 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The Pop 3 Doors Down Duck And Run Pop 3 Doors Down So I Need You Pop 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes Pop 3 Doors Down Loser Pop 3 Doors Down Here By Me Pop 3 Doors Down Be Like That Pop 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) Pop 3 Doors Down Here Without You Pop 3 Doors Down Every Time You Go - No Lyrics - Pop 3 Doors Down When You're Young - No Lyrics - Pop 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone - No Lyrics - Pop 3 Doors Down Let Me Go Pop 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself - No Lyrics - Pop 3 Doors Down Live For Today Pop 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier - No Lyrics - Pop 3 Doors Down Train - No Lyrics - Pop 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Pop 3 Doors Down ftg. Bob Seger Landing In London Pop 3 Of Hearts Arizona Rain - No Lyrics - Country 3 Of Hearts Love Is Enough - No Lyrics - Country 38 Special Hold On Loosely - No Lyrics - Pop 38 Special If I'd Been The One Pop 3oh!3 ftg. -

Lowering the Bar: the Effects of Misogyny in Rap Music

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Capstone Projects and Master's Theses Capstone Projects and Master's Theses 5-2021 Lowering the Bar: The Effects of Misogyny in Rap Music John-Paul Mackey Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes_all This Capstone Project (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects and Master's Theses at Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lowering the Bar The Effects of Misogyny in Rap Music John-Paul Mackey California State University, Monterey Bay Music & Performing Arts May 2021 Mackey 1 Table of Contents Introduction 3 The Context of Rap Music 3 Definition and Aesthetics 3 Origins 4 Early History 5 Consumption and Popularity 8 Backlash and Criticism 9 The Context of Misogyny and Misogynoir 10 Misogyny, Misogynoir, and Hegemonic Masculinity 10 Origins 12 Sociological Impact 14 Health and Behavioral Impact 15 Impact on the Media 16 The Proliferation of Misogynistic Rap 18 History 18 Other Characteristics 19 Women’s Role 20 Deflections and Dismissals 22 Responsibility for Misogynistic Rap 23 Common Misogynistic Themes in Rap 26 Overview 26 Objectification of Women 27 Mackey 2 Derogatory Terms and Stereotypes 31 Distrust and Suspicion of Women 33 Violence Against Women 35 Misogyny in Eminem’s Music 38 Effects of Misogynistic Rap 39 Desensitization 39 Reduced Self-Esteem 41 Health and Behavioral Impact 42 Sociological Impact 43 Financial Rewards 45 Promotion and Airplay 46 Misogyny in Other Genres 47 A Changing Climate 49 Backlash and Criticism of Misogynistic Rap 49 The Role of Feminism 51 Topics by Female Rappers 53 Positive Developments 56 Looking Forward 61 Works Cited 65 Mackey 3 Introduction On July 12, 2020, rapper Megan Thee Stallion was shot in the foot, allegedly by fellow musician Tory Lanez. -

The Sanctioned Antiblackness of White Monumentality: Africological Epistemology As Compass, Black Memory, and Breaking the Colonial Map

THE SANCTIONED ANTIBLACKNESS OF WHITE MONUMENTALITY: AFRICOLOGICAL EPISTEMOLOGY AS COMPASS, BLACK MEMORY, AND BREAKING THE COLONIAL MAP A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Christopher G. Roberts May 2018 Examining Committee Members: Molefi K. Asante, Advisory Chair, Africology and African American Studies Amari Johnson, Africology and African American Studies Benjamin Talton, History Serie McDougal III, External Member, San Francisco State University © Copyright 2018 by Christopher G. Roberts All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT In the cities of Richmond, Virginia; Charleston South Carolina; New Orleans, Louisiana; and Baltimore, Maryland, this dissertation endeavors to find out what can be learned about the archaeology(s) of Black memory(s) through Africological Epistemic Visual Storytelling (AEVS); their silences, their hauntings, their wake work, and their healing? This project is concerned with elucidating new African memories and African knowledges that emerge from a two-tier Afrocentric analysis of Eurocentric cartography that problematizes the dual hegemony of the colonial archive of public memory and the colonial map by using an Afrocentric methodology that deploys a Black Digital Humanities research design to create an African agentic ritual archive that counters the colonial one. Additionally, this dissertation explains the importance of understanding the imperial geographic logics inherent in the hegemonically quotidian cartographies of Europe and the United States that sanction white supremacist narratives of memory and suppress spatial imaginations and memories in African communities primarily, but Native American communities as well. It is the hope of the primary researcher that from this project knowledge will be gained about how African people can use knowledge gained from analyzing select monuments/sites of memorialization for the purposes of asserting agency, resisting, and possibly breaking the supposed correctness of the colonial map.