I We Once Lived in Caves and Other Stories by Khristian Mecom A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

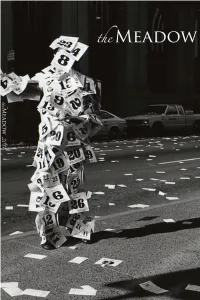

The Meadow 2011 Literary and Art Journal

MEADOW the 2011 TRUCKEE MEADOWS COMMUNITY COLLEGE Reno, Nevada The Meadow is the annual literary arts journal published ev- Editor-in-Chief ery spring by Truckee Meadows Community College in Reno, Lindsay Wilson Nevada. Students interested in the literary arts, graphic design, and creative writing are encouraged to participate on Poetry Editors the Editorial Board. Visit www.tmcc.edu/meadow for infor- Erika Bein mation and submission guidelines. Look for notices around Joe Hunt campus, in The Echo student newspaper, or contact the Editor-in-Chief at [email protected] or through the English Fiction Editor department at (775) 673-7092. Mark Maynard See our website (listed above) for information on our annual Non-Fiction Editor Cover Design and Literary and Art Contests. Only TMCC Rob Lively students are eligible for prizes. Editorial Board At this time, The Meadow is not interested in acquiring rights David Anderson to contributors’ works. All rights revert to the author or art- Melissa Cosgrove ist upon publication, and we expect The Meadow to be ac- knowledged as original publisher in any future chapbooks or Andrew Crimmins books. John Dodge JoAnn Hoskins The Meadow is indexed in The International Directory of Little Theodore Hunt Magazines and Small Presses. Janice Huntoon Our address is Editor-in-Chief, The Meadow, Truckee Mead- Arian Katsimbras ows Community College, English Department, Vista B300, Rachel Meyer 7000 Dandini Blvd., Reno, Nevada 89512. Peter Nygard The views expressed in The Meadow are solely reflective of Tony Olsen the authors’ perspectives. TMCC takes no responsibility for Drew Pearson the creative expression contained herein. -

Pieces of a Woman

PIECES OF A WOMAN Directed by Kornél Mundruczó Starring Vanessa Kirby, Shia LaBeouf, Molly Parker, Sarah Snook, Iliza Shlesinger, Benny Safdie, Jimmie Falls, Ellen Burstyn **WORLD PREMIERE – In Competition – Venice Film Festival 2020** **OFFICIAL SELECTION – Gala Presentations – Toronto International Film Festival 2020** Press Contacts: US: Julie Chappell | [email protected] International: Claudia Tomassini | [email protected] Sales Contact: Linda Jin | [email protected] 1 SHORT SYNOPSIS When an unfathomable tragedy befalls a young mother (Vanessa Kirby), she begins a year-long odyssey of mourning that touches her husband (Shia LaBeouf), her mother (Ellen Burstyn), and her midwife (Molly Parker). Director Kornél Mundruczó (White God, winner of the Prix Un Certain Regard Award, 2014) and partner/screenwriter Kata Wéber craft a deeply personal meditation and ultimately transcendent story of a woman learning to live alongside her loss. SYNOPSIS Martha and Sean Carson (Vanessa Kirby, Shia LaBeouf) are a Boston couple on the verge of parenthood whose lives change irrevocably during a home birth at the hands of a flustered midwife (Molly Parker), who faces charges of criminal negligence. Thus begins a year-long odyssey for Martha, who must navigate her grief while working through fractious relationships with her husband and her domineering mother (Ellen Burstyn), along with the publicly vilified midwife whom she must face in court. From director Kornél Mundruczó (White God, winner of the Prix Un Certain Regard Award, 2014), with artistic support from executive producer Martin Scorsese, and written by Kata Wéber, Mundruczó’s partner, comes a deeply personal, searing domestic aria in exquisite shades of grey and an ultimately transcendent story of a woman learning to live alongside her loss. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 NOTE TO USERS The original manuscript received by UMI contains pages with slanted print. Pages were microfilmed as received. This reproduction is the best copy available UMI WOMEN AND THE DYNAMIC INTERACTION OF TRADITIONAL AND CLINICAL MEDICINE ON THE BLACK SEA COAST OF TURKEY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Sylvia Wing Onder, M. -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

Execution's Doorstep: True Stories of the Innocent and Near Damned

Execution’s Doorstep Execution’s Doorstep True Stories of the Innocent and Near Damned LESLIE LYTLE Northeastern University Press Boston published by university press of new england hanover and london Northeastern University Press Published by University Press of New England, One Court Street, Lebanon, NH 03766 www.upne.com © 2008 by Northeastern University Press Printed in the United States of America 54321 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writ- ing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Members of educational institutions and organizations wishing to photocopy any of the work for classroom use, or authors and publishers who would like to obtain permission for any of the material in the work, should contact Permissions, University Press of New Eng- land, One Court Street, Lebanon, NH 03766. The statistical information and circumstances recounted in Execution’s Doorstep reflect infor- mation available prior to January 1, 2008. Song lyrics on page 233 COURTESY OF RANDAL PADGETT Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lytle, Leslie. Execution's doorstep : true stories of the innocent and near damned / Leslie Lytle. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978–1–55553–678–7 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Trials (Murder)—United States. 2. Judicial error—United States. 3. Compensation for judicial error—United States. 4. Death row inmates—United States—Biography. I. Title. kf221.m8l98 2008 345.73′02523—dc22 2008024996 University Press of New England is a member of the Green Press Initiative. -

Other Worldly Glimpses

Rhode Island College Digital Commons @ RIC Honors Projects Overview Honors Projects 4-18-2020 Other Worldly Glimpses Jordan Payeur [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects Part of the Fiction Commons Recommended Citation Payeur, Jordan, "Other Worldly Glimpses" (2020). Honors Projects Overview. 169. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects/169 This Honors is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Projects at Digital Commons @ RIC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects Overview by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RIC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OTHER WORLDLY GLIMPSES By Jordan Payeur An Honors Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in The Department of English The School of Arts and Sciences Rhode Island College 2020 2 Author’s Note For my honors project, I decided to develop my series of short stories to reflect the different types of worlds that are built within the fantasy genre. Modernly, the terms “low fantasy” and “high fantasy” have begun to be defined as the subgenres of fantasy. These two terms have been debated, some writers and/or readers having slightly different opinions on what each encompasses. In general, low fantasy is defined as a world in which there are fantastical elements, but the story takes place within the world we live. High fantasy, on the other hand, is a world imagined by the author, entirely separate from our world (though there are various things within these other worlds that may resemble ours). The first short story in this series, “What a Life”, is a modern fairytale that represents the more tradition fantasy genre. -

1997 Railroad Employee Fatalities

U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Railroad Administration 1997 Railroad Employee Fatalities: A Comprehensive Study Office of Safety July 2001 Washington, DC 20590 ® Memorandum U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Railroad Administration Date: June 18, 2001 Subject: 1997 Railroad Employee Fatalities: A Comprehensive Study From: George A. Gavalla / W - £ . Associate Administrator for Safety To: Distribution On behalf of the Office of Safety, I am pleased to distribute this report, entitled “1997 Railroad Employee Fatalities: A Comprehensive Study,” designed to promote and enhance awareness of many unsafe behaviors and conditions that typically contribute to railroad employee fatalities. By furthering our understanding of the causes of railroad employee fatalities, this report is intended to assist railroad industry stakeholders in their efforts to prevent similar tragedies. In addition to the individual narrative reports (provided in the past), this document contains the following new materials: • Yard and accident scene diagrams which accompany 28 narrative reports for calendar year 1997; • Narrative matrix entitled “Analysis of 1997 Employee Fatalities,” which highlights important elements of each fatality, particularly the possible contributing factors. This format allows the reader to walk through and analyze each fatality scenario, identifying ways the fatalities could have been prevented; • • Findings which help to identify who the majority of fatally injured employees were (i.e. craft, job position, age group, years of service); when they were fatally injured (i.e. time of year, time of day); where the incidents occurred (i.e. region, type of railroad); and most importantly, why they occurred in terms of possible contributing factors; and • Bar and pie charts which illustrate the above findings. -

Aerial Arial : a Lesson in Strength and Stamina. Ashley Elizabeth Smith University of Louisville

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2014 Aerial arial : a lesson in strength and stamina. Ashley Elizabeth Smith University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Ashley Elizabeth, "Aerial arial : a lesson in strength and stamina." (2014). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1356. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/1356 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The nivU ersity of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The nivU ersity of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AERIAL ARIAL: A LESSON IN STRENGTH AND STAMINA By Ashley Elizabeth Smith B.A., University of Kentucky, 2009 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Colleges of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Masters of Fine Arts Department of Theatre Arts University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 2014 Copyright 2014 by Ashley Elizabeth Smith All rights reserved AERIAL ARIAL: A LESSON IN STRENGTH AND STAMINA By Ashley Elizabeth Smith B.A., University of Kentucky, 2009 A Thesis Approved on April 7, 2014 By the following Thesis Committee ___________________________________________________________ Dr. Amy Steiger ___________________________________________________________ Erin Crites ___________________________________________________________ Dr. Julia C. Dietrich ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to the strongest women I know my mother Ms. -

Mary in Film

PONT~CALFACULTYOFTHEOLOGY "MARIANUM" INTERNATIONAL MARIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE (UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON) MARY IN FILM AN ANALYSIS OF CINEMATIC PRESENTATIONS OF THE VIRGIN MARY FROM 1897- 1999: A THEOLOGICAL APPRAISAL OF A SOCIO-CULTURAL REALITY A thesis submitted to The International Marian Research Institute In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree Licentiate of Sacred Theology (with Specialization in Mariology) By: Michael P. Durley Director: Rev. Johann G. Roten, S.M. IMRI Dayton, Ohio (USA) 45469-1390 2000 Table of Contents I) Purpose and Method 4-7 ll) Review of Literature on 'Mary in Film'- Stlltus Quaestionis 8-25 lli) Catholic Teaching on the Instruments of Social Communication Overview 26-28 Vigilanti Cura (1936) 29-32 Miranda Prorsus (1957) 33-35 Inter Miri.fica (1963) 36-40 Communio et Progressio (1971) 41-48 Aetatis Novae (1992) 49-52 Summary 53-54 IV) General Review of Trends in Film History and Mary's Place Therein Introduction 55-56 Actuality Films (1895-1915) 57 Early 'Life of Christ' films (1898-1929) 58-61 Melodramas (1910-1930) 62-64 Fantasy Epics and the Golden Age ofHollywood (1930-1950) 65-67 Realistic Movements (1946-1959) 68-70 Various 'New Waves' (1959-1990) 71-75 Religious and Marian Revival (1985-Present) 76-78 V) Thematic Survey of Mary in Films Classification Criteria 79-84 Lectures 85-92 Filmographies of Marian Lectures Catechetical 93-94 Apparitions 95 Miscellaneous 96 Documentaries 97-106 Filmographies of Marian Documentaries Marian Art 107-108 Apparitions 109-112 Miscellaneous 113-115 Dramas -

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List # 20 Wild Westerns: Marshals & Gunman 2 Days in the Valley (2 Discs) 2 Family Movies: Family Time: Adventures 24 Season 1 (7 Discs) of Gallant Bess & The Pied Piper of 24 Season 2 (7 Discs) Hamelin 24 Season 3 (7 Discs) 3:10 to Yuma 24 Season 4 (7 Discs) 30 Minutes or Less 24 Season 5 (7 Discs) 300 24 Season 6 (7 Discs) 3-Way 24 Season 7 (6 Discs) 4 Cult Horror Movies (2 Discs) 24 Season 8 (6 Discs) 4 Film Favorites: The Matrix Collection- 24: Redemption 2 Discs (4 Discs) 27 Dresses 4 Movies With Soul 40 Year Old Virgin, The 400 Years of the Telescope 50 Icons of Comedy 5 Action Movies 150 Cartoon Classics (4 Discs) 5 Great Movies Rated G 1917 5th Wave, The 1961 U.S. Figure Skating Championships 6 Family Movies (2 Discs) 8 Family Movies (2 Discs) A 8 Mile A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2 Discs) 10 Bible Stories for the Whole Family A.R.C.H.I.E. 10 Minute Solution: Pilates Abandon 10 Movie Adventure Pack (2 Discs) Abduction 10,000 BC About Schmidt 102 Minutes That Changed America Abraham Lincoln Vampire Hunter 10th Kingdom, The (3 Discs) Absolute Power 11:14 Accountant, The 12 Angry Men Act of Valor 12 Years a Slave Action Films (2 Discs) 13 Ghosts of Scooby-Doo, The: The Action Pack Volume 6 complete series (2 Discs) Addams Family, The 13 Hours Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ Smarter 13 Towns of Huron County, The: A 150 Year Brother, The Heritage Adventures in Babysitting 16 Blocks Adventures in Zambezia 17th Annual Lane Automotive Car Show Adventures of Dally & Spanky 2005 Adventures of Elmo in Grouchland, The 20 Movie Star Films Adventures of Huck Finn, The Hartford Public Library DVD Title List Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. -

ADJS Top 200 Song Lists.Xlsx

The Top 200 Australian Songs Rank Title Artist 1 Need You Tonight INXS 2 Beds Are Burning Midnight Oil 3 Khe Sanh Cold Chisel 4 Holy Grail Hunter & Collectors 5 Down Under Men at Work 6 These Days Powderfinger 7 Come Said The Boy Mondo Rock 8 You're The Voice John Farnham 9 Eagle Rock Daddy Cool 10 Friday On My Mind The Easybeats 11 Living In The 70's Skyhooks 12 Dumb Things Paul Kelly 13 Sounds of Then (This Is Australia) GANGgajang 14 Baby I Got You On My Mind Powderfinger 15 I Honestly Love You Olivia Newton-John 16 Reckless Australian Crawl 17 Where the Wild Roses Grow (Feat. Kylie Minogue) Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds 18 Great Southern Land Icehouse 19 Heavy Heart You Am I 20 Throw Your Arms Around Me Hunters & Collectors 21 Are You Gonna Be My Girl JET 22 My Happiness Powderfinger 23 Straight Lines Silverchair 24 Black Fingernails, Red Wine Eskimo Joe 25 4ever The Veronicas 26 Can't Get You Out Of My Head Kylie Minogue 27 Walking On A Dream Empire Of The Sun 28 Sweet Disposition The Temper Trap 29 Somebody That I Used To Know Gotye 30 Zebra John Butler Trio 31 Born To Try Delta Goodrem 32 So Beautiful Pete Murray 33 Love At First Sight Kylie Minogue 34 Never Tear Us Apart INXS 35 Big Jet Plane Angus & Julia Stone 36 All I Want Sarah Blasko 37 Amazing Alex Lloyd 38 Ana's Song (Open Fire) Silverchair 39 Great Wall Boom Crash Opera 40 Woman Wolfmother 41 Black Betty Spiderbait 42 Chemical Heart Grinspoon 43 By My Side INXS 44 One Said To The Other The Living End 45 Plastic Loveless Letters Magic Dirt 46 What's My Scene The Hoodoo Gurus -

Vanguard Label Discography Was Compiled Using Our Record Collections, Schwann Catalogs from 1953 to 1982, a Phono-Log from 1963, and Various Other Sources

Discography Of The Vanguard Label Vanguard Records was established in New York City in 1947. It was owned by Maynard and Seymour Solomon. The label released classical, folk, international, jazz, pop, spoken word, rhythm and blues and blues. Vanguard had a subsidiary called Bach Guild that released classical music. The Solomon brothers started the company with a loan of $10,000 from their family and rented a small office on 80 East 11th Street. The label was started just as the 33 1/3 RPM LP was just gaining popularity and Vanguard concentrated on LP’s. Vanguard commissioned recordings of five Bach Cantatas and those were the first releases on the label. As the long play market expanded Vanguard moved into other fields of music besides classical. The famed producer John Hammond (Discoverer of Robert Johnson, Bruce Springsteen Billie Holiday, Bob Dylan and Aretha Franklin) came in to supervise a jazz series called Jazz Showcase. The Solomon brothers’ politics was left leaning and many of the artists on Vanguard were black-listed by the House Un-American Activities Committive. Vanguard ignored the black-list of performers and had success with Cisco Houston, Paul Robeson and the Weavers. The Weavers were so successful that Vanguard moved more and more into the popular field. Folk music became the main focus of the label and the home of Joan Baez, Ian and Sylvia, Rooftop Singers, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Doc Watson, Country Joe and the Fish and many others. During the 1950’s and early 1960’s, a folk festival was held each year in Newport Rhode Island and Vanguard recorded and issued albums from the those events.