Resistance to Equality Elizabeth M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Criminal Justice Response to Women Who Kill an Interview with Helena Kennedy Sheila Quaid and Catherine Itzin Introduction

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sunderland University Institutional Repository The criminal justice response to women who kill An interview with Helena Kennedy Sheila Quaid and Catherine Itzin Introduction This chapter is based on an interview with Helena Kennedy QC by Catherine Itzin. It has been edited into the form of a narrative, covering a range of issues relating to women and the criminal justice system, and in particular explores the question of 'Why do women kill?'. In Helena Kennedy's experience of defending women, she asserts that most women kill in desperation, in self... defence or in the defence of their children. Women's experience of violence and escape from violence has received much critical comment and campaigning for law reform over the past few years and some cases such as Sara Thornton, Kiranjit Ahluwalia and Emma Humphreys have achieved a high public profile as campaigners have fought for their release from life sentences. All three women had sustained years of violence and abuse from their partners and had killed in their attempts to stop the violence. Who women kill Women are rarely involved in serial killing and they almost never go out and plan the anonymous killing of a victim with whom who they have no connection at all. For the most part women kill people they know and primarily these people are men. They kill within the domestic arena: they kill their husbands, their lovers, their boyfriends and sometimes they kill their children. Occasion... ally it might stretch beyond the domestic parameter, but the numbers are incredibly small, and when women kill it is when something is going very wrong with their domestic environment. -

PROVOCATION’: READRESSING the LANDMARK THAT OUTFLANKED the LAW of MURDER – a COMMENT on ‘REGINA V

Indian Journal of Legal Research & Advancements Volume 1 Issue 1, October 2020 EXPATIATION OF ‘PROVOCATION’: READRESSING THE LANDMARK THAT OUTFLANKED THE LAW OF MURDER – A COMMENT ON ‘REGINA v. Kiranjit Ahluwalia’ Ritik Gupta* ABSTRACT Metaphorically, understanding with practicality makes the concept more explicable, and the same did the case of Regina v. Kiranjit Ahluwalia (“Ahluwalia”) on which the author will be commenting in this piece. Firstly, he will expound that how this judgment broadened the compass of ‘provocation’ and influenced the whole world through a new facet respecting domestic violence and then how the three appeals performed the interrogator, that grilled the legitimacy of directions placed in the precedents in conformance with the contemporary law. Secondly, he will scrutinise the fluctuations escorted due to the inducement of this watershed moment to statues and acts and why those became desiderata to bring into effect. Thirdly, he will draw a distinction in the context of ‘provocation’ and ‘diminished responsibility’ amongst English and Indian law, and discourse that why the latter needs an overhaul. Further, he will tag the tribulations which women have to bear when the law does not perceive the circumstance in all facets. Lastly, he will conclude in a concise way and portray the remainder. TABLE OF CONTENTS * The author is a student of B.A. LL.B. (Hons.) at Fairfield Institute of Management and Technology, GGSIP University, New Delhi. He may be reached at [email protected]. The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the institution’s with which the author is affiliated. -

Gender Representations in Women's Cinema of the South Asian Diaspora

Universidad de Salamanca Facultad de Filología / Departamento de Filología Inglesa HYBRID CINEMAS AND NARRATIVES: GENDER REPRESENTATIONS IN WOMEN’S CINEMA OF THE SOUTH ASIAN DIASPORA Tesis Doctoral Jorge Diego Sánchez Directora: Olga Barrios Herrero 2015 © Photograph by Sohini Roychowdhury at Anjali Basu’s Wedding Ceremony (Kolkata, India), 2015. UNIVERSIDAD DE SALAMANCA FACULTAD DE FILOLOGÍA DEPARTAMENTO DE FILOLOGÍA INGLESA HYBRID CINEMAS AND NARRATIVES: GENDER REPRESENTATIONS IN WOMEN’S CINEMA OF THE SOUTH ASIAN DIASPORA Tesis para optar al grado de doctor presentada por Jorge Diego Sánchez Directora: Olga Barrios Herrero V°B° Olga Barrios Herrero Jorge Diego Sánchez Salamanca, 2015 1 INDEX INDEX Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ……………………………………………………………… 5 INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………………………….. 13 CHAPTER I THE MANY SOUTH ASIAS OF THE MIND: HISTORY OF THE SOUTH ASIAN DIASPORA …………………………………………………………………..………….. 27 1- Inwards Flight to the History of the South Asian Subcontinent ………………………. 32 1.1 The Indian Palimpsest. A Fractal Overview of the Historical Confrontations in the South Asian Subcontinent until the Establishment of the British Raj ………………………………………………….. 33 1.2 The Jewel of the Crown: the Colonial Encounter as the End Of the Integrating Diversity and the Beginning of a Categorising Society ……………………………………………………………… 38 1.3 The Construction of the Indian National Identity as a Postcolonial Abstraction: the Partition of the Religious, Linguistic and Social Distinctiveness ………………………………………………………….…. 43 2- Outwards Flight of South Asian Cultures: The Many Indian Diasporas …………….... 49 2.1 Raw Materials and Peoples: Indian Diaspora to the UK, Caribbean and East and South Africa during Colonial Times ……………..…….. 50 A. Arriving at the British Metropolis: Cotton, Labour Force and Colonising Education (1765 – 1947) …………………….. 51 B. Working for the Empire: Indentured Indian Diaspora in the Caribbean (1838 – 1917) …………………….…. -

School of Finance & Law Working Paper Series the Radical

School of Finance & Law Working Paper Series The Radical Potentialities of Biographical Methods for Making Difference(s) Visible by Elizabeth Mytton Bournemouth University No. 5. 1997 Bournemouth University, School of Finance & Law (Department of Accounting & Finance), Talbot Campus, Fern Barrow, Poole, Dorset. BH12 5BB Published 1997 by the School of Finance and Law, Bournemouth University, Talbot Campus, Fern Barrow, Poole, Dorset, BH12 5BB. For further details contact: Elizabeth Mytton School of Finance & Law Bournemouth University Fern Barrow Poole, BH12 5BB United Kingdom Tel: (00)- 01202 595206 Fax: (00)-1202-595261 Email: [email protected] ISBN 1-85899-043-2 Copyright is held by the individual authors. A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. Acknowledgements The author would like to thank Kerry Howell for his valuable guidance and Geoff Willcocks for the recognition of pedagogic studies and research. [The usual disclaimer applies.] For further information on the series, contact K. Howell, School of Finance & Law, Bournemouth University. The Radical Potentialities of Biographical Methods for Making Difference(s) Visible by Elizabeth Mytton Senior Lecturer School of Finance & Law Bournemouth University November 1997 The common law of England has been laboriously built up by a mythical figure - the figure of the reasonable man. (Herbert, Uncommon Law 1935) Abstract This paper is part of work in progress which explores the use of biographical methods and the radical potentialities there may be for making difference(s) visible. 'Radical potentialities' refers to the extent to which there are opportunities to effect change. This paper is primarily concerned with exploring prevailing narratives which generate epistemological assumptions creating a conceptual framework within which the law of provocation as it relates to women who kill their partners operates. -

WHO KILL: How the State Criminalises Women We Might Otherwise Be Burying TABLE of CONTENTS

WOMEN WHO KILL: how the state criminalises women we might otherwise be burying TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements 1 About the Contributors 2-3 Foreword by Harriet Wistrich, Director 4-6 Summary of Key Findings 7-12 1. Lack of protection from domestic abuse: triggers to women’s lethal violence 7 2. First responders when women kill 8 3. Court proceedings 8 4. Additional challenges 10 5. Expert evidence 11 6. After conviction 11 Introduction 13-17 The legal framework in England and Wales 15 Homicide in the context of intimate partner relationships 17 Methodology 18-21 Primary data collection 19 Women participants 20 Secondary data analysis 20 Study limitations 21 Key Findings: Prevalence and criminal justice outcomes for women 22-23 Key Findings: Criminal justice responses to women who kill 24-96 1. Lack of protection from domestic abuse: triggers to women’s lethal violence 24 2. First responders when women kill 33 3. Court proceedings 43 4. Additional challenges 73 5. Expert evidence 83 6. After conviction 90 TABLE OF CONTENTS CONT. Conclusion and Recommendations 97-106 Conclusion 97 Recommendations 98 1. Systemic change to address triggers to women’s lethal violence 98 2. When women kill: early stages of the criminal justice process 99 3. Court proceedings 101 4. Additional challenges 102 5. Expert evidence 102 6. After conviction 103 7. Further recommendations 105 8. Recommendations for further research 106 Appendix 1: Detailed methodology 107-118 Appendix 2: The intersection of domestic abuse, race and culture in cases involving Black and minority ethnic women in the criminal justice system 119-128 Appendix 3: Media analysis - women who kill 129-137 Appendix 4: The legal framework surrounding cases of women who kill 138-143 Endnotes 144-149 WOMEN WHO KILL: how the state criminalises women we might otherwise be burying Acknowledgements Research has been coordinated and written by Sophie Howes, with input from Helen Easton, Harriet Wistrich, Katy Swaine Williams, Clare Wade QC, Pragna Patel and Julie Bindel, Nic Mainwood, Hannana Siddiqui. -

Gender Equality and Cultural Claims: Testing Incompatibility Through Analysis of UK Policies on Minority 'Cultural Practices M

Gender equality and cultural claims: testing incompatibility through analysis of UK policies on minority ‘cultural practices’ 1997-2007 Moira Dustin Gender Institute, London School of Economics and Political Science Degree of PhD UMI Number: U615669 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615669 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 2 8% of chapter 3 and 25% of chapter 4 appeared in a previously published paper I co authored with my supervisor: ‘UK Initiatives on Forced Marriage: Regulation, Dialogue and Exit’ by Anne Phillips and Moira Dustin, Political Studies, October 2004, vol 52, pp531-551.1 was responsible for most of the empirical research in the paper. Apart from this, I confirm that the work presented in the thesis is my own. Moira Dustin i/la ^SL. 3 Many thanks to Anne Phillips, and also to family, friends and colleagues for their support and advice. ' h e $ £ Snlisl'i ibraryo* Political mo Economic Soenoe 4 Abstract Debates about multiculturalism attempt to resolve the tension that has been identified in Western societies between the cultural claims of minorities and the liberal values of democracy and individual choice. -

POLICING DOMESTIC VIOLENCE the Work of Southall Under the Law and New Guidelines Pertaining to Domestic Violence

CJM CRnaNALJUSnCEMATTEBS POLICING DOMESTIC VIOLENCE The work of Southall under the law and new guidelines pertaining to domestic violence. We have Black Sisters come to the conclusion that the whole complaints system, including the Police Southall Black Sisters is a women's Complaints Authority is deeply centre which has been in existence since unsatisfactory and completely 1983. It carries out a wide variety of unworkable. activities but its main work is giving The question of spousal homicide, advice and counselling to women who where domestic violence forms part of face domestic violence. Most of the the background to the case has occupied women who are clients of Southall Black us for some time. For a number of years press charges. Sisters are Asian, as the area is we have fought for convictions of men predominantly an Asian area, but we who have killed women in their families. Arguments for inaction also work with a large number of women We have also been involved in the legal Some aspects of multi-culturalism have from both minority and English case of Kiranjit Ahluwalia who was the effect of denying women from backgrounds who use our facilities as convicted of murder in December 1989. minorities access to protection from the the local women's centre. Women also We took her instructions when the appeal police. The police are particularly come from outside the immediate was being prepared. We have also worked reluctant to intervene in Asian catchment area because the centre has with Sara Thornton, also convicted of communities because of their perception acquired a national reputation. -

Interviewing the Embodiment of Political Evil

University of Huddersfield Repository Gavin, Helen Jealous Men but Evil Women: The Double Standard in Cases of Domestic Homicide Original Citation Gavin, Helen (2015) Jealous Men but Evil Women: The Double Standard in Cases of Domestic Homicide. In: Perceiving Evil: Evil, Women and the Feminine. Inter-Disciplinary Press. ISBN 978- 1-84888-005-4 This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/27269/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Jealous Men but Evil Women: The Double Standard in Cases of Domestic Homicide Helen Gavin Abstract In 1989, Sara Thornton killed her abusive husband with a knife, after years of abuse and threats to her daughter. She was convicted of murder and sentenced to life imprisonment. Also in 1989, Kiranjit Ahluwalia soaked her husband’s bedclothes with petrol and set them alight. -

Bc Chronology

How To Murder A Man And Get Away With It This is an address by The International False Rape Timeline. A conference on this subject will be held shortly, although its title is less direct and far less honest. Unsurprisingly, the event is being held on-line. As you can see, it is called Women Who Kill: how the state criminalises women we might otherwise be burying - in other words, women who are convicted of murder should not be. Ever? If you know anything about the women behind this perversion of the rule of law, you will realise that is a rhetorical question. The Centre For Women’s Justice is a registered charity, which according to its mission statement “aims to advance the human rights of women and girls in England and Wales by - holding the state to account for failures in the prevention of violence against women and girls and - challenging discrimination against women within the criminal justice system”. Don’t be deceived by the rhetoric anymore than by the name. Strangely, for a feminist organisation, it has zero commitment to diversity; all ten of its trustees are women. Biological women. The two women behind it are the lawyer Harriet Wistrich and her lover, the journalist Julie Bindel. Wistrich’s mother Enid was a formidable anti-censorship campaigner; she died last year aged 91. Sadly, the apple fell a long way from the tree; Bindel is even worse: attacking pornography and prostitution - both social evils created and perpetuated by the mythical patriarchy. Those present at this conference/meeting/launch will include the gullible Samira Ahmed, and four women who are anything but gullible: Sally Challen, Pragna Patel, Elizabeth Sheehy, and Naz Shah. -

The Depths of Dishonour: Hidden Voices and Shameful Crimes

The depths of dishonour: Hidden voices and shameful crimes An inspection of the police response to honour-based violence, forced marriage and female genital mutilation December 2015 © HMIC 2015 ISBN: 978-1-911194-64-4 www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmic Contents Foreword ................................................................................................................... 5 Summary ................................................................................................................... 8 Recommendations ................................................................................................. 17 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................ 20 Background .......................................................................................................... 20 About this inspection ............................................................................................. 22 About this report ................................................................................................... 26 2. The nature of honour-based violence (HBV), forced marriage (FM) and female genital mutilation (FGM) ............................................................................ 28 Honour-based violence ......................................................................................... 28 Forced marriage ................................................................................................... 30 Female genital mutilation -

Daily Express

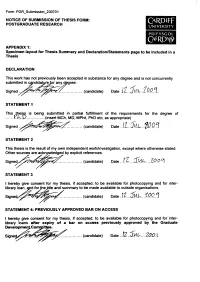

Form: PGR_Submission_200701 NOTICE OF SUBMISSION OF THESIS FORM: POSTGRADUATE RESEARCH Ca r d if f UNIVERSITY PRIFYSGOL CAERDVg) APPENDIX 1: Specimen layout for Thesis Summary and Declaration/Statements page to be included in a Thesis DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not concurrently submitted in capdidatyrefor any degree. S i g n e d ................. (candidate) Date . i.L.. 'IP .Q . STATEMENT 1 This Thesis is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Y .l \.D ..................(insert MCh, MD, MPhil, PhD etc, as appropriate) Signed (candidate) Date .. STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. Sig (candidate) Date STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loan, apd for thefitle and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signe4x^^~^^^^pS^^ ....................(candidate) Date . STATEMENT 4: PREVIOUSLY APPROVED BAR ON ACCESS I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loans after expiry of a bar on access previously approved by the Graduate Developme^Committee. (candidate) Date 3ml-....7.00.1 EXPRESSIONS OF BLAME: NARRATIVES OF BATTERED WOMEN WHO KILL IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY DAILY EXPRESS i UMI Number: U584367 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Legal Defences for Battered Women Who Kill: the Battered Woman Syndrome, Expert Testimony and Law Reform

Legal Defences for Battered Women who Kill: The Battered Woman Syndrome, Expert Testimony and Law Reform. by Juliette Casey. Submitted in satisfaction ofthe requirements for the degree ofPh.D in the University ofEdinburgh 1999. \ <, I certify that this thesis is entirely my own work and that no part ofit has been published previously in the form in which it is now presented. I dedicate this thesis to the memory ofEmma Humphreys. TABLE OF CONTENTS. Introduction 5 Part One 10 Cases for the Individualisation ofthe Reasonable Man in Provocation. .................. .. 10 Introduction 10 Chapter One ................................................................ .. 20 Interviews with Advocates ..................................................... .. 20 Introduction 20 The Advocates and their Responses . .. 21 Chapter Two................................................................ .. 38 Feminism and Law 38 Introduction 38 Part One: General Discussion ofFeminism 39 British Feminist Jurisprudence 39 American Feminist Jurisprudence 45 Part Two:Feminism, Honour and Provocation 52 Introduction 52 Honour and the Original Four Categories ofProvocation 53 The Man ofHonour, Anger as Outrage and Reason 58 The man ofHonour, Anger as Loss of SelfControl and Passion . .. 62 Feminism, Honour and Provocation in Mawgridge's Adultry Category 65 Feminism, Honour and Proportionality 67 Feminism, Honour and Reasonableness 69 Conclusion to Part One 74 Part Two 80 A Comparative Analysis ofEach ofthe Three Defences in Britain 80 Introduction 80 Chapter Three ..............................................................