The Criminal Justice Response to Women Who Kill an Interview with Helena Kennedy Sheila Quaid and Catherine Itzin Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Psychology: an International 11

WOMEN'S STUDIES LIBRARIAN The University ofWisconsin System EMINIST ERIODICALS A CURRENT LISTING OF CONTENTS VOLUME 13, NUMBER 3 FALL 1993 Published by Phyllis Holman Weisbard Women's Studies Librarian University of Wisconsin System 430 Memorial Library / 728 State Street Madison, Wisconsin 53706 (608) 263-5754 EMINIST ERIODICALS A CURRENT LISTING OF CONTENTS Volume 13, Number 3 Fall 1993 Periodical literature is the cutting edge of women's scholarship, feminist theory, and much ofwomen'sculture. Feminist Periodicals: A Current Listing of Contents is published by the Office of the University of Wisconsin System Women's Studies Librarian on a quarterly basis with the intent of increasing pUblic awareness of feminist periodicals. It is our hope that Feminist Periodicals will serve several purposes: to keep the reader abreast of current topics in feminist literature; to increase readers' familiarity with a wide spectrum of feminist periodicals; and to provide the requisite bibliographic information should a reader wish to subscribe to ajournal or to obtain a particular article at her library or through interlibrary lOan. (Users will need to be aware of the limitations of the new copyright law with regard to photocopying of copyrighted materials.) Tabie of contents pages from current issues of majorfeminist journals are reproduced in each issue ofFeminist Periodicals, preceded by a comprehensive annotated listing of all journals we have selected. As pUblication schedules vary enormously, not every periodical will have table of contents pages reproduced in each issue of IT. The annotated listing provides the following information on each journal: 1. Year of first publication. 2. Frequency of pUblication. -

London Reclaim the Night 2019 Still Angry After 40 Years

STILL ANGRY AFTER 40 YEARS LONDON RECLAIM THE NIGHT 2019 A MARCH TO END MALE VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN. Saturday 23rd November 2019 - Assemble at 6pm at Hanover Square, London, W1 for a women-only march http://www.reclaimthenight.co.uk LONDON RECLAIM THE NIGHT 2019 To mark the United Nations International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, take to the streets and demand justice for rape survivors, freedom from harassment, and an end to all forms of male violence. Join Reclaim the Night 2019! WHY RECLAIM THE NIGHT? • Nearly 1 in 3 women in the UK will experience domestic abuse in their lifetime • Every year around 400,000 women are sexually assaulted and 80,000 women are raped • Around 66,000 women are living with FGM in England & Wales, and 20,000 girls are at risk • 79% of women aged 18-24 recently reported that sexual harrassment was 'the norm' on nights out. • The NSPCC found that teenage girls aged 13-15 were as likely to experience abusive relationships as women aged 16 or more • Two women are murdered by their partners or ex-partners every week Reclaim The Night remains as relevant now as it did in 1977 when the first marches took place in the UK. The women only march will be followed by a rally which is open to all. Speakers include Mandu Reid (Women's Equality Party), Lee Nurse (Justice for Women) and Frances Scott (50:50 Parliament). Further details about the event including the men's vigil will be available at: www.reclaimthenight.co.uk JOIN THE FEMINIST RESURGENCE! To join LFN go to www.londonfeministnetwork.org.uk or our facebook page and follow the instructions. -

How to Organise a Reclaim the Night March

How to organise a Reclaim the Night march First of all, it’s good to point out what Reclaim the Night (RTN) is. It’s traditionally a women’s march to reclaim the streets after dark, a show of resistance and strength against sexual harassment and assault. It is to make the point that women do not have the right to use public space alone, or with female friends, especially at night, without being seen as ‘fair game’ for harassment and the threat or reality of sexual violence. We should not need chaperones (though that whole Mr Darcy scene is arguably a bit cool, as is Victorian clothing, but not the values). We should not need to have a man with us at all times to protect us from other men. This is also the reason why the marches are traditionally women-only; having men there dilutes our visi- ble point. Our message has much more symbolism if we are women together. How many marches do you see through your town centre that are made up of just women? Exactly. So do think before ruling out your biggest unique selling point. Anyway, the RTN marches first started in several cities in Britain in November 1977, when the Women’s Liberation Movement (WLM) was last at its height, a period called the Second Wave. The idea for the marches was copied from co-ordinated midnight marches across West German cities earlier that same year in April 1977. The marches came to stand for women’s protest against all forms of male violence against women, but particularly sexual vio- lence. -

Bitch the Politics of Angry Women

Bitch The Politics of Angry Women Kylie Murphy Bachelor of Arts with First Class Honours in Communication Studies This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University 2002. DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. Kylie Murphy ii ABSTRACT ‘Bitch: the Politics of Angry Women’ investigates the scholarly challenges and strengths in retheorising popular culture and feminism. It traces the connections and schisms between academic feminism and the feminism that punctuates popular culture. By tracing a series of specific bitch trajectories, this thesis accesses an archaeology of women’s battle to gain power. Feminism is a large and brawling paradigm that struggles to incorporate a diversity of feminist voices. This thesis joins the fight. It argues that feminism is partly constituted through popular cultural representations. The separation between the academy and popular culture is damaging theoretically and politically. Academic feminism needs to work with the popular, as opposed to undermining or dismissing its relevancy. Cultural studies provides the tools necessary to interpret popular modes of feminism. It allows a consideration of the discourses of race, gender, age and class that plait their way through any construction of feminism. I do not present an easy identity politics. These bitches refuse simple narratives. The chapters clash and interrogate one another, allowing difference its own space. I mine a series of sites for feminist meanings and potential, ranging across television, popular music, governmental politics, feminist books and journals, magazines and the popular press. -

Newsletter No4 09-10

Feminist Archive North Newsletter No. 4 Winter 2009-10 www.feministarchivenorth.org.uk/ blog - http://fanorth.wordpress.com/ T-shirts from the Helen John archive This bumper Newsletter celebrates Women’s ensure our materials are properly preserved, Activism, with reports on recent donations to so we have an article on the Life of a FAN and activities we have been involved in Donation, and news of a recent grant from over the last year. These activities are the the Co-op, which was only achieved through reason why it’s been so long since the last the initiative of a volunteer. issue. Primarily, the two volunteers who It’s also important that FAN makes use of usually work on the Newsletter have been new methods for the electronic age. One totally focussed on completing our Education example is the Learning Journey, which went Pack, now on-line and called a Learning live in April, as Feminist Activism – Education Journey. But more of that later. and Job Opportunities, thanks to training Here, you can read about exciting new from the MLA (Museums, Libraries & donations from the Bolton Women’s Archives). Another is the user-friendly guide Liberation Group Archive, which chronicles to blogging. the wealth of their achievements from 1971 But until everyone has the blogging habit, we to 1994, and about the ongoing work of the still include brief news items. Justice for Women campaign. The Treasures Finally, it’s good to note that this issue has series features an archive donated by the been much more of a team effort, with six veteran women’s peace campaigner Helen volunteers making contributions. -

PROVOCATION’: READRESSING the LANDMARK THAT OUTFLANKED the LAW of MURDER – a COMMENT on ‘REGINA V

Indian Journal of Legal Research & Advancements Volume 1 Issue 1, October 2020 EXPATIATION OF ‘PROVOCATION’: READRESSING THE LANDMARK THAT OUTFLANKED THE LAW OF MURDER – A COMMENT ON ‘REGINA v. Kiranjit Ahluwalia’ Ritik Gupta* ABSTRACT Metaphorically, understanding with practicality makes the concept more explicable, and the same did the case of Regina v. Kiranjit Ahluwalia (“Ahluwalia”) on which the author will be commenting in this piece. Firstly, he will expound that how this judgment broadened the compass of ‘provocation’ and influenced the whole world through a new facet respecting domestic violence and then how the three appeals performed the interrogator, that grilled the legitimacy of directions placed in the precedents in conformance with the contemporary law. Secondly, he will scrutinise the fluctuations escorted due to the inducement of this watershed moment to statues and acts and why those became desiderata to bring into effect. Thirdly, he will draw a distinction in the context of ‘provocation’ and ‘diminished responsibility’ amongst English and Indian law, and discourse that why the latter needs an overhaul. Further, he will tag the tribulations which women have to bear when the law does not perceive the circumstance in all facets. Lastly, he will conclude in a concise way and portray the remainder. TABLE OF CONTENTS * The author is a student of B.A. LL.B. (Hons.) at Fairfield Institute of Management and Technology, GGSIP University, New Delhi. He may be reached at [email protected]. The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the institution’s with which the author is affiliated. -

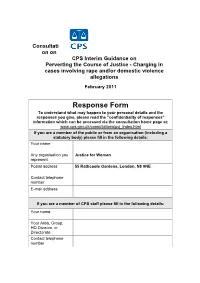

Response Form

Consultati on on CPS Interim Guidance on Perverting the Course of Justice - Charging in cases involving rape and/or domestic violence allegations February 2011 Response Form To understand what may happen to your personal details and the responses you give, please read the "confidentiality of responses" information which can be accessed via the consultation home page at: www.cps.gov.uk/consultations/pcj_index.html If you are a member of the public or from an organisation (including a statutory body) please fill in the following details: Your name Any organisation you Justice for Women represent Postal address 55 Rathcoole Gardens, London, N8 9NE Contact telephone number E-mail address If you are a member of CPS staff please fill in the following details: Your name Your Area, Group, HQ Division, or Directorate Contact telephone number Justice for Women contributes to the global effort to eradicate male violence against women, which includes sexual and domestic violence. Our focus is on the criminal justice system of England and Wales. Justice for Women works to identify and change those areas of law, policy and practice relating to male violence against women, where women are discriminated against on the basis of their gender. Justice for Women was established in 1990 as a feminist campaigning organisation that supports and advocates on behalf of women who have fought back against or killed violent male partners. Over the past twenty years, Justice for Women has developed considerable legal expertise in this area, and has been involved in a number of significant cases at the Court of Appeal that have resulted in women’s original murder convictions being overturned, including Kiranjit Ahluwahlia, Emma Humphreys, Sara Thornton and Diana Butler. -

Gender Representations in Women's Cinema of the South Asian Diaspora

Universidad de Salamanca Facultad de Filología / Departamento de Filología Inglesa HYBRID CINEMAS AND NARRATIVES: GENDER REPRESENTATIONS IN WOMEN’S CINEMA OF THE SOUTH ASIAN DIASPORA Tesis Doctoral Jorge Diego Sánchez Directora: Olga Barrios Herrero 2015 © Photograph by Sohini Roychowdhury at Anjali Basu’s Wedding Ceremony (Kolkata, India), 2015. UNIVERSIDAD DE SALAMANCA FACULTAD DE FILOLOGÍA DEPARTAMENTO DE FILOLOGÍA INGLESA HYBRID CINEMAS AND NARRATIVES: GENDER REPRESENTATIONS IN WOMEN’S CINEMA OF THE SOUTH ASIAN DIASPORA Tesis para optar al grado de doctor presentada por Jorge Diego Sánchez Directora: Olga Barrios Herrero V°B° Olga Barrios Herrero Jorge Diego Sánchez Salamanca, 2015 1 INDEX INDEX Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ……………………………………………………………… 5 INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………………………….. 13 CHAPTER I THE MANY SOUTH ASIAS OF THE MIND: HISTORY OF THE SOUTH ASIAN DIASPORA …………………………………………………………………..………….. 27 1- Inwards Flight to the History of the South Asian Subcontinent ………………………. 32 1.1 The Indian Palimpsest. A Fractal Overview of the Historical Confrontations in the South Asian Subcontinent until the Establishment of the British Raj ………………………………………………….. 33 1.2 The Jewel of the Crown: the Colonial Encounter as the End Of the Integrating Diversity and the Beginning of a Categorising Society ……………………………………………………………… 38 1.3 The Construction of the Indian National Identity as a Postcolonial Abstraction: the Partition of the Religious, Linguistic and Social Distinctiveness ………………………………………………………….…. 43 2- Outwards Flight of South Asian Cultures: The Many Indian Diasporas …………….... 49 2.1 Raw Materials and Peoples: Indian Diaspora to the UK, Caribbean and East and South Africa during Colonial Times ……………..…….. 50 A. Arriving at the British Metropolis: Cotton, Labour Force and Colonising Education (1765 – 1947) …………………….. 51 B. Working for the Empire: Indentured Indian Diaspora in the Caribbean (1838 – 1917) …………………….…. -

School of Finance & Law Working Paper Series the Radical

School of Finance & Law Working Paper Series The Radical Potentialities of Biographical Methods for Making Difference(s) Visible by Elizabeth Mytton Bournemouth University No. 5. 1997 Bournemouth University, School of Finance & Law (Department of Accounting & Finance), Talbot Campus, Fern Barrow, Poole, Dorset. BH12 5BB Published 1997 by the School of Finance and Law, Bournemouth University, Talbot Campus, Fern Barrow, Poole, Dorset, BH12 5BB. For further details contact: Elizabeth Mytton School of Finance & Law Bournemouth University Fern Barrow Poole, BH12 5BB United Kingdom Tel: (00)- 01202 595206 Fax: (00)-1202-595261 Email: [email protected] ISBN 1-85899-043-2 Copyright is held by the individual authors. A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. Acknowledgements The author would like to thank Kerry Howell for his valuable guidance and Geoff Willcocks for the recognition of pedagogic studies and research. [The usual disclaimer applies.] For further information on the series, contact K. Howell, School of Finance & Law, Bournemouth University. The Radical Potentialities of Biographical Methods for Making Difference(s) Visible by Elizabeth Mytton Senior Lecturer School of Finance & Law Bournemouth University November 1997 The common law of England has been laboriously built up by a mythical figure - the figure of the reasonable man. (Herbert, Uncommon Law 1935) Abstract This paper is part of work in progress which explores the use of biographical methods and the radical potentialities there may be for making difference(s) visible. 'Radical potentialities' refers to the extent to which there are opportunities to effect change. This paper is primarily concerned with exploring prevailing narratives which generate epistemological assumptions creating a conceptual framework within which the law of provocation as it relates to women who kill their partners operates. -

WHO KILL: How the State Criminalises Women We Might Otherwise Be Burying TABLE of CONTENTS

WOMEN WHO KILL: how the state criminalises women we might otherwise be burying TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements 1 About the Contributors 2-3 Foreword by Harriet Wistrich, Director 4-6 Summary of Key Findings 7-12 1. Lack of protection from domestic abuse: triggers to women’s lethal violence 7 2. First responders when women kill 8 3. Court proceedings 8 4. Additional challenges 10 5. Expert evidence 11 6. After conviction 11 Introduction 13-17 The legal framework in England and Wales 15 Homicide in the context of intimate partner relationships 17 Methodology 18-21 Primary data collection 19 Women participants 20 Secondary data analysis 20 Study limitations 21 Key Findings: Prevalence and criminal justice outcomes for women 22-23 Key Findings: Criminal justice responses to women who kill 24-96 1. Lack of protection from domestic abuse: triggers to women’s lethal violence 24 2. First responders when women kill 33 3. Court proceedings 43 4. Additional challenges 73 5. Expert evidence 83 6. After conviction 90 TABLE OF CONTENTS CONT. Conclusion and Recommendations 97-106 Conclusion 97 Recommendations 98 1. Systemic change to address triggers to women’s lethal violence 98 2. When women kill: early stages of the criminal justice process 99 3. Court proceedings 101 4. Additional challenges 102 5. Expert evidence 102 6. After conviction 103 7. Further recommendations 105 8. Recommendations for further research 106 Appendix 1: Detailed methodology 107-118 Appendix 2: The intersection of domestic abuse, race and culture in cases involving Black and minority ethnic women in the criminal justice system 119-128 Appendix 3: Media analysis - women who kill 129-137 Appendix 4: The legal framework surrounding cases of women who kill 138-143 Endnotes 144-149 WOMEN WHO KILL: how the state criminalises women we might otherwise be burying Acknowledgements Research has been coordinated and written by Sophie Howes, with input from Helen Easton, Harriet Wistrich, Katy Swaine Williams, Clare Wade QC, Pragna Patel and Julie Bindel, Nic Mainwood, Hannana Siddiqui. -

An Archive of the Women's Liberation Movement

Title: An Archive of The Women’s Liberation Movement: a Document of Social & Legislative Change Contributor’s Name: Polly Russell Contributor’s Address: The British Library, 96 Euston Road, London NW1 2DB Abstract: This paper offers introduction to the material available to researchers in the recently launched ‘Sisterhood & After: an Oral History of the Women’s Liberation Movement’ archive at the British Library. Drawing from the archive’s oral history recordings, I demonstrate how they can be used to examine the ways that legislative changes are experienced and raise questions about the relation between legislative change, cultural change and the Women’s Liberation Movement (WLM). The paper argues that these oral history recordings provide a unique opportunity to reflect on the ways that legislative and structural change were experienced by WLM activists in their everyday lives. Biography: Dr Polly Russell works as a Curator at The British Library where, among other things, she manages collections relating to women’s history. Polly was the British Library’s project lead for the 2010 - 2013 ‘Sisterhood & After: the Women’s Liberation Oral History Project’. Polly is currently managing a project to digitize and make freely available all issues of the feminist magazine ‘Spare Rib.’ Word count: 3993 1 Introduction: Nearly a century since women were first given the vote, issues pertaining to women’s rights and sexual equality are regularly in the news and feminist campaigns are on the rise in the UK.i This contemporary feminist moment is inextricably connected to a long history of women’s activism, of which the most well-known are the Suffragette campaigns of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and then the Women’s Liberation Movement (WLM) of the late 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. -

Gender Equality and Cultural Claims: Testing Incompatibility Through Analysis of UK Policies on Minority 'Cultural Practices M

Gender equality and cultural claims: testing incompatibility through analysis of UK policies on minority ‘cultural practices’ 1997-2007 Moira Dustin Gender Institute, London School of Economics and Political Science Degree of PhD UMI Number: U615669 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615669 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 2 8% of chapter 3 and 25% of chapter 4 appeared in a previously published paper I co authored with my supervisor: ‘UK Initiatives on Forced Marriage: Regulation, Dialogue and Exit’ by Anne Phillips and Moira Dustin, Political Studies, October 2004, vol 52, pp531-551.1 was responsible for most of the empirical research in the paper. Apart from this, I confirm that the work presented in the thesis is my own. Moira Dustin i/la ^SL. 3 Many thanks to Anne Phillips, and also to family, friends and colleagues for their support and advice. ' h e $ £ Snlisl'i ibraryo* Political mo Economic Soenoe 4 Abstract Debates about multiculturalism attempt to resolve the tension that has been identified in Western societies between the cultural claims of minorities and the liberal values of democracy and individual choice.