Lusitanization and Bakhtinian Perspectives on the Role Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Portuguese Language in Angola: Luso-Creoles' Missing Link? John M

Portuguese language in Angola: luso-creoles' missing link? John M. Lipski {presented at annual meeting of the AATSP, San Diego, August 9, 1995} 0. Introduction Portuguese explorers first reached the Congo Basin in the late 15th century, beginning a linguistic and cultural presence that in some regions was to last for 500 years. In other areas of Africa, Portuguese-based creoles rapidly developed, while for several centuries pidginized Portuguese was a major lingua franca for the Atlantic slave trade, and has been implicated in the formation of many Afro- American creoles. The original Portuguese presence in southwestern Africa was confined to limited missionary activity, and to slave trading in coastal depots, but in the late 19th century, Portugal reentered the Congo-Angola region as a colonial power, committed to establishing permanent European settlements in Africa, and to Europeanizing the native African population. In the intervening centuries, Angola and the Portuguese Congo were the source of thousands of slaves sent to the Americas, whose language and culture profoundly influenced Latin American varieties of Portuguese and Spanish. Despite the key position of the Congo-Angola region for Ibero-American linguistic development, little is known of the continuing use of the Portuguese language by Africans in Congo-Angola during most of the five centuries in question. Only in recent years has some attention been directed to the Portuguese language spoken non-natively but extensively in Angola and Mozambique (Gonçalves 1983). In Angola, the urban second-language varieties of Portuguese, especially as spoken in the squatter communities of Luanda, have been referred to as Musseque Portuguese, a name derived from the KiMbundu term used to designate the shantytowns themselves. -

A Discourse Analysis of Code-Switching Practices Among Angolan Migrants in Cape Town, South Africa

A Discourse Analysis of Code-Switching Practices among Angolan Migrants in Cape Town, South Africa Dinis Fernando da Costa (2865747) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Department of Linguistics, University of the Western Cape SUPERVISOR: PROF. Charlyn Dyers June 2010 i Abstract A Discourse Analysis of Code-Switching Practices among Angolan Migrants in Cape Town, South Africa Dinis Fernando da Costa This thesis is an extension of my BA (Honours) research essay, completed in 2008. This thesis is a more in-depth study of the issues involved in code switching among Angolan migrants living in Cape Town by increasing the scope of the research. The significance of this study lies in the fact that code-switching practices of Angolans in the Diaspora has not yet been investigated, and I hope that this potentially rich vein of research will be taken up by future studies. In this thesis, I explore the code-switching practices of long-term Angolans migrants in Cape Town when they interact with those who have been here for a much shorter period. In my Honours research essay, I revealed a tendency among those who have lived in Cape Town for some time to code-switch from Portuguese to English even in the presence of more recent migrants from Angola, who have little or no mastery of English. This thesis thus considers the effects of space, discourses of power, language ideologies and attitudes on the patterns of inter- and intra-sentential code-switching by these long-term migrants in interaction with each other as well as with the more recent “Angolan arrivals” in Cape Town. -

Table of Contents

José N’dongala Kizombalove Methodology – teachers course Kizomba teachers course José N’dongala Kizombalove Methodology Teachers Course KIZOMBA TEACHERS1 COURSE José N’dongala Kizombalove Methodology – teachers course Kizomba teachers course José N’dongala Kizombalove Methodology Teachers Course Syllabus « José N’dongala Kizombalove Methodology » teachers course by José Garcia N’dongala. Copyright © First edition, January 2012 by José Garcia N’dongala President Zouk Style vzw/asbl (Kizombalove Academy) KIZOMBA TEACHERS COURSE 2 José N’dongala Kizombalove Methodology – teachers course Kizomba teachers course “Vision without action is a daydream. Action without vision is a nightmare” Japanese proverb “Do not dance because you feel like it. Dance because the music wants you to dance” Kizombalove proverb Kizombalove, where sensuality comes from… 3 José N’dongala Kizombalove Methodology – teachers course Kizomba teachers course All rights reserved. No part of this syllabus may be stored or reproduced in any way, electronically, mechanically or otherwise without prior written permission from the Author. 4 José N’dongala Kizombalove Methodology – teachers course Kizomba teachers course Table of contents 1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 9 2 DANCE AND MUSIC ................................................................................................. 12 2.1 DANCING A HUMAN PHENOMENON ......................................................................... -

Dissertation.Pdf

Declaration I hereby declare that AN ANALYSIS OF VERBAL AFFIXES IN KIKONGO WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO FORM AND FUNCTION is to the best of my knowledge and belief, original and my own work. The material has not been submitted, either in whole or part, for a degree at this or any other institution of learning. The contents of this study are the product of my intellect, except where due acknowledgement is made in the text or somewhere else. The strengths and weaknesses of this work are wholly my own. ………………………………….. Mbiavanga Fernando Abstract The relation between verbal affixes and their effect on the predicate argument structure of the verbs that host them has been the focus of many studies in linguistics, with special reference to Bantu languages in recent years. Given the colonial policy on indigenous languages in Angola, Kikongo, as is the case of other Bantu languages in that country, has not been sufficiently studied. This study explores the form and function of six verbal affixes, including the order in which they occur in the verb stem. The study maintains that the applicative and causative are valency-increasing verbal affixes and, as such, give rise to double object constructions in Kikongo. The passive, reciprocal, reflexive and stative are valency-decreasing and, as such, they reduce the valency of the verb by one object. This study also suggests that Kikongo is a symmetrical object language in which both objects appear to have equal status. ii Ded ication In memory of my father, and for my mother who always believes that ‘mungwa kani kunsuka zenzila’ better late than never iii Acknowledgements ‘If the LORD does not build the house, the work of the builders is useless; if the LORD does not protect the city, it does no good for the sentries to stand guard. -

Angola – Researched and Compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on 11 March 2011

Angola – Researched and compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on 11 March 2011. Information on whether the following languages Lingala and Bakongo/Kicongo are spoken in Angola. A report by the Home Office UK Border Agency under the heading ‘Geography’ states: “Angola is located in southern Africa, bordering the South Atlantic Ocean, between Namibia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It also has borders with the Republic of the Congo, Namibia and Zambia. The overall land area of the country is 1,246,700 sq km. The ethnic groups that make up the Angolan population are the Ovimbundu (37%), Kimbundu (25%), Bakongo (13%), mestico (mixed European and native African) (2%), European (1%), and other ethnic groups (22%)…”(United Kingdom Border Agency (1 September 2010) Country of Origin Information Report – Angola pg. 6 par. 1.02) It also states: “According to Travlang.com (accessed on 16 June 2010), the official language of Angola is Portuguese. Other languages spoken include Umbundu, Kimbundu, Kongo, Chokwe, Lwena and Lunda. As regards the languages spoken by the people of Cabinda, Ethnologue (accessed on 22 July 2010) lists Koongo (aka Kongo, Kikongo, Kikoongo, Congo, Cabinda) and Yombe (aka Kiyombe, Kiombi, Lombe and Bayombe) as the languages spoken in that province. According to a Global Security report about Cabinda, “Cabindês is the National Language of Cabinda. However, a large number of Cabinda Citizens speak French. The Cabindans at least, for the literate among them, are 90% French speaking and only 10% speak Portuguese.” (ibid) A report by the United States Department of State states: “Ethnic groups: Ovimbundu 37%, Kimbundu 25%, Bakongo 13%, mixed racial 2%, European 1%. -

Revising the Bantu Tree

Cladistics Cladistics (2018) 1–20 10.1111/cla.12353 Revising the Bantu tree Peter M. Whiteleya, Ming Xuea and Ward C. Wheelerb,* aDivision of Anthropology, American Museum of Natural History, 200 Central Park West, New York, NY, 10024-5192, USA; bDivision of Invertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History, 200 Central Park West, New York, NY, 10024-5192, USA Accepted 15 June 2018 Abstract Phylogenetic methods offer a promising advance for the historical study of language and cultural relationships. Applications to date, however, have been hampered by traditional approaches dependent on unfalsifiable authority statements: in this regard, historical linguistics remains in a similar position to evolutionary biology prior to the cladistic revolution. Influential phyloge- netic studies of Bantu languages over the last two decades, which provide the foundation for multiple analyses of Bantu socio- cultural histories, are a major case in point. Comparative analyses of basic lexica, instead of directly treating written words, use only numerical symbols that express non-replicable authority opinion about underlying relationships. Building on a previous study of Uto-Aztecan, here we analyse Bantu language relationships with methods deriving from DNA sequence optimization algorithms, treating basic vocabulary as sequences of sounds. This yields finer-grained results that indicate major revisions to the Bantu tree, and enables more robust inferences about the history of Bantu language expansion and/or migration throughout sub-Saharan Africa. “Early-split” versus “late-split” hypotheses for East and West Bantu are tested, and overall results are com- pared to trees based on numerical reductions of vocabulary data. Reconstruction of language histories is more empirically based and robust than with previous methods. -

The Angolan Revolution, Vol. I: the Anatomy of an Explosion (1950-1962)

The Angolan revolution, Vol. I: the anatomy of an explosion (1950-1962) http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.crp2b20033 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org The Angolan revolution, Vol. I: the anatomy of an explosion (1950-1962) Author/Creator Marcum, John Publisher Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press (Cambridge) Date 1969 Resource type Books Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Angola, Portugal, United States, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, Congo, Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Coverage (temporal) 1950 - 1962 Source Northwestern University Libraries, Melville J. Herskovits Library of African Studies, 967.3 M322a, v. -

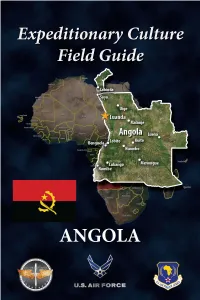

ECFG-Angola-2020R.Pdf

About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success. ECFG The guide consists of 2 parts: Part 1 introduces “Culture General,” the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment. Angola Part 2 presents “Culture Specific” Angola, focusing on unique cultural features of Angolan society and is designed to complement other pre-deployment training. It applies culture- general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society. All human beings have culture, and individuals within a culture share a general set of beliefs and values. -

TEACHING ESL in ANGOLA 1 Teaching English As a Second

TEACHING ESL IN ANGOLA 1 Teaching English as a Second Language in Angola Dare Guild Education 408: Critical Aspects of Teaching English as a Second Language Robin Rhodes-Crowell May 4, 2018 TEACHING ESL IN ANGOLA 2 Abstract: This paper explores the historical context of the Republic of Angola and the current education system in the country’s state of reparation following three decades of war. The Civil War, which ended recently in 2002, left many without access to school, low literacy levels, and many destroyed school buildings. In its wake, many teachers were rushed to start teaching, and there still are not enough. Here are the effects of war on an education system and what Angola needs from future English as a Second Language (ESL) teachers. Introduction: The Republic of Angola is a country heavy in history. The capital of Angola is Luanda and there is a country population of approximately 28.8 million (The World Bank, 2018). As a formal Portuguese colony, the most widespread use of a single language is Portuguese, which is spoken by approximately seventy-one percent of the country. There are an estimated thirty-nine other languages spoken within Angola, including many African Languages. The three co- primary languages of Angola include Umbundu, Kimbundu, and Kikongo (Oyebade, 2007). Both English and French are taught in Angola, depending on the region one is more commonly taught than the other. “Western education is greatly valued in Angola, and it is seen as a means to enhance social and economic status” (Oyebade, 2007). Qualified teachers and qualified English teachers are both in high demand in Angola, however in order to understand the current struggle in Angola’s education system a better understanding of their historical background is vital. -

1. a Survey of African Languages Harald Hammarström

1. A survey of African languages Harald Hammarström 1.1. Introduction The African continent harbors upwards of 2,000 spoken indigenous languages – more than a fourth of the world’s total. Using ISO 639-3 language/dialect divisions and including extinct languages for which evidence exists, the tally comes to 2,169. The main criterion for the ISO 639-3 language identification is mutual intelligibil- ity, but these divisions are not infrequently conflated with sociopolitical criteria. This causes the tally to be higher than if the language/dialect division were to be based solely on intelligibility. Based solely on mutual intelligibility, the number would be approximately 85 % of the said figure (Hammarström 2015: 733), thus around 1,850 mutually unintelligible languages in Africa. A lower count of 1,441 is obtained by treating dialect chains whose endpoints are not mutually intelligible as one and the same language (Maho 2004). The amount of information available on the language situation varies across different areas of Africa, but the entire continent has been surveyed for spoken L1 languages on the surface at least once. However, so-called “hidden” languages that escaped earlier surveys continue to be discovered every year. These are all languages that are spoken by a (usually aging) fraction of a population who other- wise speak another (already known) language. The least surveyed areas of Africa include Northern Nigeria, Eastern Chad, South Sudan and various spots in the Republic of Congo, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Angola. The situation is entirely different with respect to sign languages (cf. Padden 2010: 19). -

A Sociolinguistic Study at the Regional Hospital of Malanje (Angola)

ISSN: 2317-2347 – v. 9, n. 2 (2020) Todo o conteúdo da RLR está licenciado sob Creative Commons Atribuição 4.0 Internacional For a linguistic policy in health services: a sociolinguistic study at the Regional Hospital of Malanje (Angola) / Por uma política linguística nos serviços de saúde: um estudo sociolinguístico do Hospital Regional de Malanje (Angola) Ezequiel Pedro José Bernardo * Master in Sociolinguistics, assistant professor at the Higher Institute of Educational Sciences / ISCED- Cabinda / Angola. Head of Portuguese Language Teaching and Research Department. http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2649-1501 Alexandre António Timbane ** Post-Doctor in Orthographic Studies at the State University of São Paulo Júlio de Mesquita Filho-UNESP (2015), Post-Doctor in Forensic Linguistics at the Federal University of Santa Catarina-UFSC (2014), Doctor of Linguistics and Portuguese Language (2013) by UNESP, Master in Mozambican Linguistics and Literature (2009) from Eduardo Mondlane University - Mozambique (UEM). He holds a BA and BA in Teaching French as a Foreign Language (2005) from the Pedagogical University-Mozambique (UP). Professor at UNILAB (Campus dos Malês, BA), member of the Africa-Brazil Research Group: knowledge production, civil society, development and global citizenship. http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2061-9391 Received: May, 22th, 2020. Approved: June, 03th, 2020. How to cite this article: BERNARDO, Ezequiel Pedro José; TIMBANE, Alexandre António. For a linguistic policy in health services: a sociolinguistic study at the Regional Hospital of Malanje (Angola). Revista Letras Raras. Campina Grande, v. 9, n. 2, p. 268-290, jun. 2020. * [email protected] ** [email protected] http://dx.doi.org/10.35572/rlr.v9i2.1584 268 ISSN: 2317-2347 – v. -

The Bantoid Languages

THE BANTOID LANGUAGES Roger Blench DRAFT ONLY NOT TO BE QUOTED WITHOUT PERMISSION Roger Blench Kay Williamson Educational Foundation 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/ Fax. 0044-(0)1223-560687 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0)7967-696804 E-mail [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm The Bantoid languages: a monograph Draft not for circulation. Front matter TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................................... 1 2. THEORIES AND METHODS................................................................................................................... 1 2.1 Lexicostatistics and other mathematical methods ..............................................................................................1 2.2 Shared innovations ................................................................................................................................................2 2.3 Historical reconstruction.......................................................................................................................................3 3. HISTORICAL OVERVIEW...................................................................................................................... 3 4. [EAST] BENUE-CONGO........................................................................................................................... 8 4.1 Overview.................................................................................................................................................................8