The Incredible Shrinking Universe of Stocks the Causes and Consequences of Fewer U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Response: Just Eat Takeaway.Com N. V

NON- CONFIDENTIAL JUST EAT TAKEAWAY.COM Submission to the CMA in response to its request for views on its Provisional Findings in relation to the Amazon/Deliveroo merger inquiry 1 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 1. In line with the Notice of provisional findings made under Rule 11.3 of the Competition and Markets Authority ("CMA") Rules of Procedure published on the CMA website, Just Eat Takeaway.com N.V. ("JETA") submits its views on the provisional findings of the CMA dated 16 April 2020 (the "Provisional Findings") regarding the anticipated acquisition by Amazon.com BV Investment Holding LLC, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Amazon.com, Inc. ("Amazon") of certain rights and minority shareholding of Roofoods Ltd ("Deliveroo") (the "Transaction"). 2. In the Provisional Findings, the CMA has concluded that the Transaction would not be expected to result in a substantial lessening of competition ("SLC") in either the market for online restaurant platforms or the market for online convenience groceries ("OCG")1 on the basis that, as a result of the Coronavirus ("COVID-19") crisis, Deliveroo is likely to exit the market unless it receives the additional funding available through the Transaction. The CMA has also provisionally found that no less anti-competitive investors were available. 3. JETA considers that this is an unprecedented decision by the CMA and questions whether it is appropriate in the current market circumstances. In its Phase 1 Decision, dated 11 December 20192, the CMA found that the Transaction gives rise to a realistic prospect of an SLC as a result of horizontal effects in the supply of food platforms and OCG in the UK. -

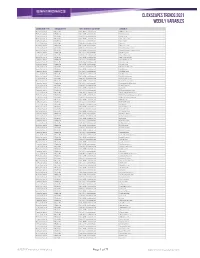

Clickscapes Trends 2021 Weekly Variables

ClickScapes Trends 2021 Weekly VariableS Connection Type Variable Type Tier 1 Interest Category Variable Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 1075koolfm.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 8tracks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 9gag.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment abs-cbn.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment aetv.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ago.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment allmusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amazonvideo.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amphitheatrecogeco.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment applemusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archambault.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archive.org Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment artnet.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment atomtickets.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audiobooks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audioboom.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandcamp.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandsintown.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment barnesandnoble.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bellmedia.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bgr.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bibliocommons.com -

Online Transportation Price War: Indonesian Style

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Klaipeda University Open Journal Systems SAKTI HENDRA PRAMUDYA ONLINE TRANSPORTATION PRICE WAR: INDONESIAN STYLE ONLINE TRANSPORTATION PRICE WAR: INDONESIAN STYLE Sakti Hendra Pramudya1 Universitas Bina Nusantara (Indonesia), University of Pécs (Hungary) ABStrAct thanks to the brilliant innovation of the expanding online transportation companies, the Indonesian people are able to obtain an affor- dable means of transportation. this three major ride-sharing companies (Go-Jek, Grab, and Uber) provide services which not only limited to transportation service but also providing services for food delivery, courier service, and even shopping assistance by utili- zing gigantic armada of motorbikes and cars which owned by their ‘driver partners’. these companies are competing to gain market share by implementing the same strategy which is offering the lowest price. this paper would discuss the Indonesian online trans- portation price war by using price comparison analysis between three companies. the analysis revealed that Uber was the winner of the price war, however, their ‘lowest price strategy’ would lead to their downfall not only in Indonesia but in all of South East Asia. KEYWOrDS: online transportation companies, price war, Indonesia. JEL cODES: D40, O18, O33 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15181/rfds.v29i3.2000 Introduction the idea of ride-hailing was unfamiliar to Indonesian people. Before the inception (and followed by the large adoption) of smartphone applications in Indonesia, the market of transportation service was to- tally different. the majority of middle to high income Indonesian urban dwellers at that time was using the conventional taxi as their second option of transportation after their personal car or motorbike. -

Meituan 美團 (The “Company”) Is Pleased to Announce the Audited Consolidated Results of the Company for the Year Ended December 31, 2020

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. (A company controlled through weighted voting rights and incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) (Stock code: 3690) ANNOUNCEMENT OF THE RESULTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2020 The Board of Directors (the “Board”) of Meituan 美團 (the “Company”) is pleased to announce the audited consolidated results of the Company for the year ended December 31, 2020. These results have been audited by the Auditor in accordance with International Standards on Auditing, and have also been reviewed by the Audit Committee. In this announcement, “we,” “us” or “our” refers to the Company. KEY HIGHLIGHTS Financial Summary Unaudited Three Months Ended December 31, 2020 December 31, 2019 As a As a percentage percentage Year-over- Amount of revenues Amount of revenues year change (RMB in thousands, except for percentages) Revenues 37,917,504 100.0% 28,158,253 100.0% 34.7% Operating (loss)/profit (2,852,696) (7.5%) 1,423,860 5.1% (300.3%) (Loss)/profit for the period (2,244,292) (5.9%) 1,460,285 5.2% (253.7%) Non-IFRS Measures: Adjusted EBITDA (589,128) (1.6%) 2,178,650 7.7% (127.0%) Adjusted net (loss)/profit (1,436,520) (3.8%) 2,270,219 8.1% (163.3%) Year Ended December 31, 2020 -

Southeast Asia New Economy

July 29, 2020 Strategy Focus Southeast Asia New Economy Understanding ASEAN's Super Apps • Grab and Gojek started as ride hailing companies and have expanded to food and parcel delivery, e-wallet and other daily services, solidifying their "Super App" status in ASEAN. • Bloomberg reported in April 2019 that both companies had joined the "decacorn" ranks, valuing Grab at US$14bn and Gojek at US$10bn. • Both Grab and Gojek have stated their intentions to list by 2023/24. Building on our June 14, 2020 ASEAN Who’s Who report, we take a closer look at Grab and Gojek, two prominent Southeast Asian app providers that achieved Super App status. Practicality vs. time spent: The ASEAN population spends 7-10 hours online daily (Global Web Index as of 3Q19), of which 80% is on social media and video streaming sites. While ride hailing services command relatively low usage hours, the provision of a reliable alternative to ASEAN's (except for Singapore's) underdeveloped public transport has made both "must own" apps. Based on June 2020 App Annie data, 29% and 27% of the ASEAN population had downloaded the Grab and Gojek apps, respectively. Merchant acquisition moving to center stage: A price war and exorbitant incentives/ subsidies characterized customer acquisition strategies until Grab acquired Uber’s Southeast Asian operations in March 2018. We now see broader ride hailing pricing discipline. Grab and Gojek have turned to merchant acquisition as their focus shifts to online food delivery business (and beyond). ASEAN TAMs for ride hailing of US$25bn and online food delivery of US$20bn by 2025E: Our sector models focus on ASEAN’s middle 40% household income segment, which we see as the target audience for both businesses. -

At the Global Food Safety Conference 2018

+17TH EDITION GFSC 1,200 DELEGATES 2018 CONTENT in numbers 86% +80% 53 of delegates rank this event plan to join us better than other countries The Global Food Safety Conference � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 4 Mike Taylor, Former FDA Deputy Commissioner � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 16 5 again in 2019 comparable events Programme at a Glance � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 5 Xiaoqun He, Deputy Director General of Registration DAYS Department, CNCA � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 16 of sessions, Michel Leporati, Executive Secretary, ACHIPIA meetings and DAY 1: TUESDAY 6TH MARCH 2018 events (Agencia Chilena para la Calidad e Inocuidad Alimentaria) � � � 17 PRE-CONFERENCE SESSION: Dr. Stephen Ostroff, Deputy Commissioner, Office of Foods GFSI & YOU & Veterinary Medicine, U.S. Food & Drug Administration, FDA � � � � 17 Katsuki Kishi, General Manager, Quality Management Depart- Jason Feeney, CEO, FSA � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 17 ment, ÆON Retail Co., Ltd. � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 6 Bill Jolly, Chief Assurance Strategy Officer, New Zealand 8 8 3 4 3rd Andy Ransom, CEO, Rentokil Initial � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 6 Ministry for Primary Industries � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 17 65 36 Special Tech Discovery GFSI award iteration Peter Freedman, Managing Director, The Consumer Speakers Exhibitors -

Food Delivery Platforms: Will They Eat the Restaurant Industry's Lunch?

Food Delivery Platforms: Will they eat the restaurant industry’s lunch? On-demand food delivery platforms have exploded in popularity across both the emerging and developed world. For those restaurant businesses which successfully cater to at-home consumers, delivery has the potential to be a highly valuable source of incremental revenues, albeit typically at a lower margin. Over the longer term, the concentration of customer demand through the dominant ordering platforms raises concerns over the bargaining power of these platforms, their singular control of customer data, and even their potential for vertical integration. Nonetheless, we believe that restaurant businesses have no choice but to embrace this high-growth channel whilst working towards the ideal long-term solution of in-house digital ordering capabilities. Contents Introduction: the rise of food delivery platforms ........................................................................... 2 Opportunities for Chained Restaurant Companies ........................................................................ 6 Threats to Restaurant Operators .................................................................................................... 8 A suggested playbook for QSR businesses ................................................................................... 10 The Arisaig Approach .................................................................................................................... 13 Disclaimer .................................................................................................................................... -

On-Demand Grocery Disruption

QUARTERLY SHAREHOLDER LETTER Topic: On-demand Grocery Disruption 31 March 2021 Dear Shareholder, Until the great Covid boost of 2020, grocery shopping was slower to move online than many categories. Demand was muted for a few reasons: groceries have lowish ticket sizes – lower, at least, than consumer electronics or high fashion – and low margins; people tend to buy food from companies they trust (particularly fresh food); shopping behaviour is sticky due to the relatively habitual, high frequency nature of grocery shopping, and barriers such as delivery fees were off-putting. On the other hand, the supply side struggled with complicated supply chains and difficult-to-crack economics. However, the lengthy Covid pandemic has encouraged people to experiment at a time when the level of digital adoption has made it a whole lot easier for suppliers to reach scale. Unsurprisingly, recent surveys indicate that most people who tried online grocery shopping during the pandemic will continue to do it post Covid. We therefore expect continued growth in online grocery penetration, and within online grocery, on-demand services that deliver in a hurry are likely to keep growing faster, from less than 10% of the total online grocery bill in most markets today. Ready when you are This letter focuses on the threats and opportunities facing companies from the growth in on-demand grocery shopping. We look at on-demand specifically as we think it will be the most relevant channel for online groceries in EM, and could be the most disruptive. The Fund is exposed to the trend in several ways. -

Boston San Francisco Munich London

Internet & Digital Media Monthly August 2018 BOB LOCKWOOD JERRY DARKO Managing Director Senior Vice President +1.617.624.7010 +1.415.616.8002 [email protected] [email protected] BOSTON SAN FRANCISCO HARALD MAEHRLE LAURA MADDISON Managing Director Senior Vice President +49.892.323.7720 +44.203.798.5600 [email protected] [email protected] MUNICH LONDON INVESTMENT BANKING Raymond James & Associates, Inc. member New York Stock Exchange/SIPC. Internet & Digital Media Monthly TECHNOLOGY & SERVICES INVESTMENT BANKING GROUP OVERVIEW Deep & Experienced Tech Team Business Model Coverage Internet / Digital Media + More Than 75 Investment Banking Professionals Globally Software / SaaS + 11 Senior Equity Research Technology-Enabled Solutions Analysts Transaction Processing + 7 Equity Capital Markets Professionals Data / Information Services Systems | Semiconductors | Hardware + 8 Global Offices BPO / IT Services Extensive Transaction Experience Domain Coverage Vertical Coverage Accounting / Financial B2B + More than 160 M&A and private placement transactions with an Digital Media Communications aggregate deal value of exceeding $25 billion since 2012 E-Commerce Consumer HCM Education / Non-Profit + More than 100 public equities transactions raising more than Marketing Tech / Services Financial $10 billion since 2012 Supply Chain Real Estate . Internet Equity Research: Top-Ranked Research Team Covering 25+ Companies . Software / Other Equity Research: 4 Analysts Covering 40+ Companies RAYMOND JAMES / INVESTMENT BANKING OVERVIEW . Full-service firm with investment banking, equity research, institutional sales & trading and asset management – Founded in 1962; public since 1983 (NYSE: RJF) – $6.4 billion in FY 2017 revenue; equity market capitalization of approximately $14.0 billion – Stable and well-capitalized platform; over 110 consecutive quarters of profitability . -

India Internet a Closer Look Into the Future We Expect the India Internet TAM to Grow to US$177 Bn by FY25 (Excl

EQUITY RESEARCH | July 27, 2020 | 10:48PM IST India Internet A Closer Look Into the Future We expect the India internet TAM to grow to US$177 bn by FY25 (excl. payments), 3x its current size, with our broader segmental analysis driving the FY20-25E CAGR higher to 24%, vs 20% previously. We see market share likely to shift in favour of Reliance Industries (c.25% by For the exclusive use of [email protected] FY25E), in part due to Facebook’s traffic dominance; we believe this partnership has the right building blocks to create a WeChat-like ‘Super App’. However, we do not view India internet as a winner-takes-all market, and highlight 12 Buy names from our global coverage which we see benefiting most from growth in India internet; we would also closely watch the private space for the emergence of competitive business models. Manish Adukia, CFA Heather Bellini, CFA Piyush Mubayi Nikhil Bhandari Vinit Joshi +91 22 6616-9049 +1 212 357-7710 +852 2978-1677 +65 6889-2867 +91 22 6616-9158 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 85e9115b1cb54911824c3a94390f6cbd Goldman Sachs India SPL Goldman Sachs & Co. LLC Goldman Sachs (Asia) L.L.C. Goldman Sachs (Singapore) Pte Goldman Sachs India SPL Goldman Sachs does and seeks to do business with companies covered in its research reports. As a result, investors should be aware that the firm may have a conflict of interest that could affect the objectivity of this report. -

Internet Technology in the Economic Sector: Gojek Expansion in Southeast Asia Rina Tridana1

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 558 Proceedings of the Asia-Pacific Research in Social Sciences and Humanities Universitas Indonesia Conference (APRISH 2019) Internet Technology in the Economic Sector: Gojek Expansion in Southeast Asia Rina Tridana1 1 Universitas Indonesia *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Current political and economic developments and even daily social life cannot be separated from the Internet. The Internet makes it possible to read the news, express our thoughts, shop, check the latest movies, or even book a flight or a hotel room. This is only a short list of the activities that can be done on the Internet with the help of a cell phone and various applications that are installed to increase the users‘ mobility. Keywords: Internet, Economics, Southeast Asia, Gojek, Neoliberalism 1. INTRODUCTION 4.88% a year later. After that economic growth tended Current political and economic developments and to increase from 5.03% to 5.07% in 2017, and it has even daily social life cannot be separated from the improved since then. Internet. The Internet makes it possible to read the Even though Indonesian economic growth slowed news, express our thoughts, shop, check the latest in 2014 because of the impact of the 2008 economic movies, or even book a flight or a hotel room. This is recession, Indonesia‘s economic growth has surpassed only a short list of the activities that can be done on other ASEAN countries. 2 According to the the Internet with the help of a cell phone and various International Monetary Fund‘s Report of October applications that increase the user‘s mobility. -

Global Consumer Survey List of Brands June 2018

Global Consumer Survey List of Brands June 2018 Brand Global Consumer Indicator Countries 11pingtai Purchase of online video games by brand / China stores (past 12 months) 1688.com Online purchase channels by store brand China (past 12 months) 1Hai Online car rental bookings by provider (past China 12 months) 1qianbao Usage of mobile payment methods by brand China (past 12 months) 1qianbao Usage of online payment methods by brand China (past 12 months) 2Checkout Usage of online payment methods by brand Austria, Canada, Germany, (past 12 months) Switzerland, United Kingdom, USA 7switch Purchase of eBooks by provider (past 12 France months) 99Bill Usage of mobile payment methods by brand China (past 12 months) 99Bill Usage of online payment methods by brand China (past 12 months) A&O Grocery shopping channels by store brand Italy A1 Smart Home Ownership of smart home devices by brand Austria Abanca Primary bank by provider Spain Abarth Primarily used car by brand all countries Ab-in-den-urlaub Online package holiday bookings by provider Austria, Germany, (past 12 months) Switzerland Academic Singles Usage of online dating by provider (past 12 Italy months) AccorHotels Online hotel bookings by provider (past 12 France months) Ace Rent-A-Car Online car rental bookings by provider (past United Kingdom, USA 12 months) Acura Primarily used car by brand all countries ADA Online car rental bookings by provider (past France 12 months) ADEG Grocery shopping channels by store brand Austria adidas Ownership of eHealth trackers / smart watches Germany by brand adidas Purchase of apparel by brand Austria, Canada, China, France, Germany, Italy, Statista Johannes-Brahms-Platz 1 20355 Hamburg Tel.