The Makings of a Recital

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Magenta Cyan Yellow Black Dvd Booklet Page 1 Page 12

MAGENTA CYAN YELLOW BLACK DVD BOOKLET Credits Executive Producer: Brett Baker Producer / Sound Engineer / Editor: Richard Scott of RAS Audio Services Accompanist: John Wilson Recorded at: Peel Hall, the Crescent University Salford 3rd-5th September 2012 Photography: John Stirzaker Program Notes: Joanna Cambray-Young Design: GK Graphic Design Thanks My thanks go to John Wilson for his expert playing, Duncan Winfield and Richard Rock for the use of Peel Hall at Salford University. I would like to thank Steve Dillon and Ron Holz for helping me source the music and the many bands in the USA, Australia and New Zealand who allowed me to trawl through their extensive libraries in search of this rare material. I would like to thank my good friend Gerard Klaucke for his inspired designs and I would also like to thank my family and friends for putting up with all the practice. Finally I would like to thank Michael Rath and Chris Beaumont for their continued support in this project. Instruments Rath R4 rose brass bell, yellow bass tuning slide, heavy valve cap, and 41b lead pipe. The Baroque Sackbut is based upon a version made by Anton Drewelwelz in 1595 in Nuremburg Germany. “Brett Baker plays exclusively Michael Rath Brass Instruments” PAGE 12 PAGE 1 MAGENTA CYAN YELLOW BLACK DVD BOOKLET Introduction the United States, he maintained a home in Newcornerstown, Ohio, and for many This CD is a celebration of rarely played trombone years served as the conductor of the Hyperion Band. solos from the beginnings of virtuoso playing on the sackbut, Yingling was also a composer of band music. -

Homer Rodeheaver: Reverend Trombone Douglas Yeo Historic

Homer Rodeheaver: Reverend Trombone Douglas Yeo Historic Brass Society Journal (peer-reviewed) Volume 27, 2015 The Historic Brass Society Journal (ISSN1045-4616) is published annually by the Historic Brass Society, Inc. 148 W. 23rd Street, #5F New York, NY 10011 USA YEO 1 Homer Rodeheaver: Reverend Trombone Douglas Yeo Introduction Since his death in 1955, Homer Rodeheaver (1880–1955) has slipped into obscurity, an astonishing fact given that he played the trombone for as many as 100 million people in his lifetime. While not nearly so accomplished as the great trombone soloists of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries such as Arthur Pryor, Simone Mantia, and Leo Zimmerman, Rodeheaver’s use of the trombone in Christian evangelistic meetings—par- ticularly during the years (1910–30) when he was song leader for William Ashley “Billy” Sunday—had an impact on American religious and secular culture that continues today. Rodeheaver’s tree of influence includes many other trombone-playing evangelists and song leaders, including Clifford Barrows, song leader for the evangelistic crusades1 of William Franklin “Billy” Graham. While Homer Rodeheaver was one of the most successful publishers of Christian songbooks and hymnals of the modern era—he owned copyrights to many of the most popular gospel2 songs of the first half of the twentieth century—and was the owner of and a recording artist with one of the first record companies devoted primarily to Christian music, the focus of this article is on Rodeheaver as trombonist and trombone icon, his use of the trombone as a tool in leading large congregations in singing, the particular instruments he used, his trombone recordings, and his legacy and influence in inspiring and encouraging others to utilize the trombone as a tool for large-scale Christian evangelism. -

Suggested Solos for Tuba Euphonium (Symbiosisduo

Gail Robertson - Clinic Handout FMEA 2011 Convention Suggested EUPHONIUM and TROMBONE solos for students to use at Solo and Ensemble Festivals: (Please check the current FBA list to make sure they are still on it!) Solos that are Best for 6th Graders: (1st year players) Air Noble Jacques Robert Conqueror Leonard B. Smith/Leonard Falcone Happy Song Edmund J. Siennicki Pied Piper Forrest L. Buchtel The Rooster Edmund J. Siennicki Solos that are best for 7th graders: In the Hall of the Mountain King Edvard Grieg/G. E. Holmes Minuet in G J.S. Bach/Ronald C. Dishinger Minstrel Boy Forrest L. Buchtel Polovetsian Dances Alexander Borodin/Forrest L. Buchtel Sparkles Floyd O. Harris The Young Prince Floyd O. Harris Solos that are Best for 8th Graders: Asleep in the Deep Henry W. Petrie/Harold L. Walters Brass Bangles Floyd O. Harris Carnival of Venice Henry W. Davis Deep River David Uber Evening in the country Bela Bartok/Floyd O. Harris Honor and Arms Frederick Handel/Allen Ostrander The Jolly Peasant Robert Schumann/G. E. Holmes March of the Marionette Charles Gounod/Harold L. Walters Ocean Beach Floyd O. Harris Pavane Pour Infante Défunte Maurice Ravel/Ronald Dishinger Red Canyons Clair W. Johnson Toreador’s Song form Carmen Georges Bizet/G. E. Holmes Solos that are Best for advanced 8th graders and 9th Graders: Arioso (From Cantata No. 156) Johann Sebastian Bach/H.R. Kent Concert Aria W. A. Mozart/H. Voxman Concert Rondo (k. 371) W. A. Mozart/Jay Ernst Fancy Free Clay Smith Fantasy for Trombone James Curnow Mirror Lake Edward Montgomery My Regards Edward Llewellyn Prelude and Minuet Arcangelo Corelli/Richard E. -

Teaching and Learning Jazz Trombone Dissertation

TEACHING AND LEARNING JAZZ TROMBONE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Julia M. Gendrich, B.S., M.S. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2003 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dr. William T. McDaniel, Co-Adviser _______________________________ Co-Adviser Dr. Timothy A. Gerber, Co-Adviser School of Music Dr. Jon R. Woods _______________________________ Co-Adviser School of Music ABSTRACT The purpose of the study was to identify and assess methods of teaching and learning jazz trombone improvisation that have been implemented by jazz trombone professors. Its intent was to describe learning procedures and areas of trombone study. A survey instrument was designed after interviewing 20 professional jazz trombonists. The survey was pilot-tested (n = 9) and adjustments were made. Jazz trombone professors (n = 377) were sent questionnaires, with a response rate of 28 percent after an additional reminder to all and follow-up phone calls to one-third of the sample. Of the 106 total respondents, 58 were deemed to be eligible participants as both trombonists and as teachers of jazz improvisation. Three areas were explored: 1) early stages of development, 2) teaching, and 3) trombone technique. Data showed that most of the professors (77%) had learned to improvise between 7th-12th grades. They identified the most important method of learning for themselves as listening and playing-along with recordings. Learning occurred on their own for many, though college also had an impact. Schools (K-12) were not strongly rated as being helpful in the trombonists learning to improvise (2.49 on a scale of one to five), though schools did provide many jazz performance experiences. -

Richmond Matteson: Euphonium Innovator, Teacher and Performer, with Three Recitals Of

RICHMOND MATTESON: EUPHONIUM INNOVATOR, TEACHER AND PERFORMER, WITH THREE RECITALS OF SELECTED WORKS BY FRESCOBALDI, BACH, SAINT-SAENS, HUTCHINSON, WHITE, AND OTHERS. Marcus Dickman, Jr., B.M.E., M.M. APPROVED: NWw V4 Major Professor 007k.00/ Committee mber Committee ember Dean of the College of Music Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies 3~7q o'S7 RICHMOND MATTESON: EUPHONIUM INNOVATOR, TEACHER AND PERFORMER DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By Marcus Dickman, Jr., B.M.E., M.M. Denton, Texas August, 1997 Dickman, Marcus, Jr., Richmond Matteson: Euphonium Innovator, Teacher and Performer, with Three Recitals of Selected Works By Frescobaldi, Bach, Saint-Sa~ns, Hutchinson, White and Others. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August, 1997, 97 pp., 23 examples, 3 tables, 3 appendices, and bibliography. An examination is conducted of the life, career and musical styles of Richmond Matteson, an influential jazz euphonium and tuba performer of the twentieth century. The study includes a brief history of the euphonium's role in concert bands. A description of Matteson's background as a musician and clinician including education, influences and career changes will also be discussed. Analysis of Matteson's improvisational style and a transcription from the recording Dan's Blues is included. A formal analysis of Claude T. Smith's Variations for Baritone is provided, as well as a brief biography of the composer. Matteson's stylistic traits which Smith employed for the composition of Variations for Baritone are illustrated. -

Brazilian Euphonium: Brief Historical Background and Annotated

BRAZILIAN EUPHONIUM: BRIEF HISTORICAL BACKGROUND AND ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF SELECTED SOLO AND CHAMBER WORKS By FERNANDO D. R. DOS SANTOS (DEDDOS) (Under the Direction of David Zerkel) ABSTRACT This research illustrates the development of the euphonium in Brazil. The document consists of a timeline of the euphonium in the country, and an annotated bibliography of selected solo and chamber works that employ the instrument, written by Brazilian composers. Both the timeline and the bibliography present original research. The instrument is an essential part of traditional Brazilian music such as the wind bands and popular genres. The euphonium is already considered as unique in institutions and music festivals, and concert music composers are increasing their interest in the multiple facets of this sweet-voiced instrument. However, there is no research that has been dedicated to the history of the instrument in Brazil, its participation in ensembles and genres, and its collaborative performers and composers. Also, the improvement and variety of the original repertoire after the 2000s deserves documentation, through the creation of an annotated bibliography. This document will provide a foundation for further studies by euphonium scholars, and benefit the music academy in Brazil, due to the newness of the research. INDEX WORDS: euphonium, music history, bibliography, Brazil BRAZILIAN EUPHONIUM: BRIEF HISTORICAL BACKGROUND AND ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF SELECTED SOLO AND CHAMBER WORKS By FERNANDO D. R. DOS SANTOS (DEDDOS) B. MUS., School of Music and Fine Arts of Parana State, Brazil, 2009 M.M., Duquesne University, 2013 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2016 © 2016 Fernando D. -

View Concert Program

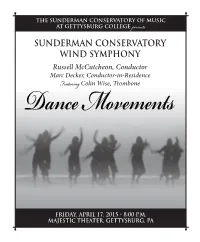

THE SUNDERMAN CONSERVATORY OF MUSIC AT GETTYSBURG COLLEGE presents SUNDERMAN CONSERVATORY WIND SYMPHONY Russell McCutcheon, Conductor Marc Decker, Conductor-in-Residence Colin Wise, Trombone Featuring Dance Movements Friday, april 17, 2015 • 8:00 p.M. MAJESTIC THEATER, GETTYSBURG, PA Program Bells Across the Atlantic .......................................................................................Adam Gorb (b. 1958) Commission Premiere Dance Movements .............................................................................................Philip Sparke (b. 1951) I. Ritmico II. Molto Vivo (for the woodwinds) III. Lento (for the brass) IV. Molto Ritmico Trauersinfonie ............................................................................................... Richard Wagner (1813 – 1883) trans. Erik Leidzen Capriccio for Solo Trombone and Wind Ensemble ............................................ Frank Gulino Colin Wise, trombone soloist Fantastic Polka ................................................................................................... Arthur Pryor (1870 – 1942) Colin Wise, trombone soloist Program Notes Adam Gorb (b. 1958) Adam Gorb is currently Head of the School of Composition at the Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester, England. He started playing piano at the age of ten and in 1976, only fifteen years old, his piano composition A Pianist’s Alphabet was performed by Susan Bradshaw on the BBC Radio 3. Gorb graduated in 1980 from Cambridge University, where he studied with Hugh Wood and Robin Holloway -

Brass Band Catalogue

Obrasso-Verlag AG | Baselstrasse 23c 4537 Wiedlisbach | Switzerland BEST FOR BRASS December 2020 BRASS BAND CATALOGUE BRASS BAND BRASS BAND & SOLOIST(S) BRASS BAND & CHOIR BRASS BAND & VOICE EASY BRASS BAND Obrasso-Verlag AG | Baselstrasse 23c 4537 Wiedlisbach | Switzerland BEST FOR BRASS Brass Band Über 1500 Kompositionen für Brass Bands aller Stärkeklassen für den mitreissenden Entertainment-Event für die packende Dar- bietung vor Fachpublikum oder für das ergreifende Festkonzert. Over 1‘500 pieces of music for Brass Bands at all levels of proficiency whether for exciting entertainment a gripping performan- ce in front of an expert audience or a stirring gall concert. Grand répertoire avec plus de 1’500 œuvres pour Brass Bands / Ensembles de Cuivres. Vous trouverez les démos de partitions en PDF dans notre boutique en ligne. Partitions pour Brass Bands. Más de 1‘500 piezas de música para bandas de metales en todos los niveles de competencia, ya sea para un entretenimiento emocionante, una actuación apasionante frente a un público experto o un conmovedor concierto de gallos. Meer dan 1.500 muziekstukken voor Brass Bands op alle niveaus, of het nu gaat om opwindend entertainment, een aangrijpen- de voorstelling voor een deskundig publiek of een opzwepend galaconcert. Easy Brass Band Diese Serie richtet sich an Brass Bands, welche über eine reduzierte Besetzung verfügen. This series is for Brass Bands with a reduced number of players. Cette serie s’adresse aux formations Brass Band qui n’ont pas une instrumentation complète. Esta serie es para bandas de Brass Band que no tienen instrumentación completa. Deze serie is voor Brass Band-banden die geen volledige instrumentatie hebben. -

A MASTER's EUPHONIUM RECITAL and PROGRAM NOTES By

A MASTER’S EUPHONIUM RECITAL AND PROGRAM NOTES by NICHOLE UNGER B.A., Westfield State University, 2010 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MUSIC Department of Music College of Music, Theatre, and Dance KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2016 Approved by: Major Professor Dr. Steven Maxwell Abstract This master’s report focuses on the history, brief analysis, and pedagogy of the four works performed on February 15, 2016 for the author’s Master’s Recital. The first chapter explains the work Pantomime by Philip Sparke. It contains a short biography of Philip Sparke, an in-depth background on the composition of the work, and a theoretical and pedagogical look at the piece. The second chapter centers on Fantasia by Gordon Jacob. This brief biography will explore Jacob’s compositional output and legacy, and the theoretical analysis will focus on his use of chromatics and the interplay between the piano and the euphonium. The pedagogical analysis will focus on performance techniques and practice. The third chapter is devoted to Blue Lake Fantasies, an unaccompanied work for solo euphonium by David Gillingham. The biography will focus on Gillingham’s contribution to euphonium repertoire, specifically and the history of where and why this work was written. There will be a concise theoretical analysis followed by a heavily pedagogical analysis, which will break down the performance techniques used in each of the five movements. The final chapter of the report is about David Werden’s euphonium arrangement for two euphoniums and piano of Believe Me If All Those Endearing Young Charms by Simone Mantia. -

The Return to the Slide from the Valve Trombone by Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth-Century Trombonists Including Arthur Pryor (1870-1942)

EVERETT, MICAH PAUL, D.M.A. The Return to the Slide from the Valve Trombone by Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth-Century Trombonists Including Arthur Pryor (1870-1942). (2005) Directed by Dr. Randy B. Kohlenberg. 101 pp. The invention of the valve radically changed the design, construction, and function of brass instruments. Following the introduction of the valve trombone during the 1820s, the slide was considered to be unwieldy and cumbersome, and therefore, inadequate for performing technically difficult music. Trombonists in America and Europe began to select the valve over the slide trombone as their instrument of preference. Even Arthur Pryor (1870-1942), who became famous throughout the world for his virtuosic slide trombone performances, began his career as a valve trombonist. The tone quality and intonation of the slide trombone were judged to be superior to those of the valve trombone, prompting trombonists in Germany and Austria to return to the slide after only a brief period of valve trombone playing. Elsewhere, trombonists believed that the technical difficulties associated with the slide negated the advantages of the slide trombone. The ease of technical execution on the valve trombone was viewed by these players as the primary consideration. Nevertheless, the slide trombone was reestablished as the instrument of preference in most of Europe and the United States between 1890 and 1925. While the deficient tone and intonation of the valve trombone were the primary considerations prompting trombonists to adopt the slide, other factors influenced this change, as well. Pryor’s slide trombone playing was among these factors. Pryor cultivated a level of virtuosic technique previously thought impossible on the slide trombone, while exhibiting a gorgeous tone and sensitive interpretation. -

Download Booklet

Peter GRAHAM Metropolis 1927 On the Shoulders of Giants • Radio City • Meditation Paramount Rhapsody • New York Movie Dale Gerrard, Narrator Philip Cobb, Trumpet • Peter Moore, Trombone Black Dyke Band • Nicholas Childs Peter Peter Graham (b. 1958) About the music Radio City (2012) GR(bA. 1H958A) M My association with Black Dyke Band goes back a When I was growing up on the west coast of Scotland, our 1 On the Shoulders of Giants (2009) 15:50 number of years and I’m thrilled that the occasion of my shortwave radio picked up programmes from across the 60th birthday is to be marked by them with this Naxos Atlantic, the American accents of the announcers 2 Fanfares 4:26 recording. From this selection of music two themes have providing a window to an evocative world far removed Elegy 6:09 3 emerged: the musical inspiration I absorbed from a period from our small Ayrshire town. These memories form the Fantasie Brillante 5:15 resident in New York City in the 1980s, and the ‘giants’ basis of Radio City. The work is set in three movements from the world of art, performance and film-making whose with a narrative written by Philip Coutts: influence also pervades this album. I’m especially I. City Noir (complete with a Philip Marlowe-type character 4 Radio City (2012) 9:32 delighted that two present day ‘giants’ of the brass world, and the dark cityscape of 1940s California); City Noir 3:42 5 London Symphony Orchestra principals Philip Cobb II. Cafe Rouge (trombonist Glenn Miller broadcast live 6 Cafe Rouge 3:37 (trumpet) and Peter Moore (trombone), both incidentally from this New York venue on numerous occasions), and Two-Minute Mile 2:13 products of the British Brass Band movement, join Black III. -

Legato Trombone a Survey of Pedagogical Resources

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 9-Feb-2010 I, Eric Blanchard , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in Trombone It is entitled: Legato Trombone: A Survey of Pedagogical Resources Student Signature: Eric Blanchard This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Timothy Anderson, MM Timothy Anderson, MM Ann Porter, PhD Ann Porter, PhD Timothy Northcut, MM Timothy Northcut, MM 3/9/2010 390 Legato Trombone: A Survey of Pedagogical Resources a document submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2010 by Eric John Blanchard B.M., Utah State University, 1999 M.M., University of Michigan, 2002 Committee Chair: Timothy Anderson UMI Number: 3426098 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3426098 Copyright 2010 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 ABSTRACT The purpose of this document was to explore the pedagogical techniques of legato trombone. Professional trombone books, method books, articles and web-pages were surveyed in order to understand legato pedagogy and to see if there were changes over the past century or differences in pedagogy throughout world regions.