A Historical Analysis of Trends in Pakhtun Ethno-Nationalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Authoritarianism and Political Party Reforms in Pakistan

AUTHORITARIANISM AND POLITICAL PARTY REFORM IN PAKISTAN Asia Report N°102 – 28 September 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. PARTIES BEFORE MUSHARRAF............................................................................. 2 A. AFTER INDEPENDENCE..........................................................................................................2 B. THE FIRST MILITARY GOVERNMENT.....................................................................................3 C. CIVILIAN RULE AND MILITARY INTERVENTION.....................................................................4 D. DISTORTED DEMOCRACY......................................................................................................5 III. POLITICAL PARTIES UNDER MUSHARRAF ...................................................... 6 A. CIVILIAN ALLIES...................................................................................................................6 B. MANIPULATING SEATS..........................................................................................................7 C. SETTING THE STAGE .............................................................................................................8 IV. A PARTY OVERVIEW ............................................................................................... 11 A. THE MAINSTREAM:.............................................................................................................11 -

SSC-SUPPL-2018-RESULT.Pdf

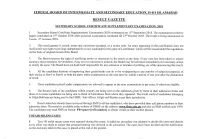

FBISE - Computer Section FEDERAL BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE AND SECONDARY EDUCATION, ISLAMABAD 1 RESULT GAZETTE OF SSC-II SUPPL. EXAMINATION 2018 SALIENT FEATURES OF RESULT ALL AREAS G r a d e W i s e D i s t r i b u t i o n Pass Sts. / Grp. / Gender Enrolled Absent Appd. R.L. UFM Fail Pass A1 A B C D E %age G.P.A EX/PRIVATE CANDIDATES Male 6965 132 6833 16 5 3587 3241 97 112 230 1154 1585 56 47.43 1.28 Female 2161 47 2114 12 1 893 1220 73 63 117 625 335 7 57.71 1.78 1 SCIENCE Total : 9126 179 8947 28 6 4480 4461 170 175 347 1779 1920 63 49.86 1.40 Male 1086 39 1047 2 1 794 252 0 2 7 37 159 45 24.07 0.49 Female 1019 22 997 4 3 614 380 1 0 18 127 217 16 38.11 0.91 2 HUMANITIES Total : 2105 61 2044 6 4 1408 632 1 2 25 164 376 61 30.92 0.70 Total : 11231 240 10991 34 10 5888 5093 171 177 372 1943 2296 124 46.34 1.27 Grand Total : 11231 240 10991 34 10 5888 5093 171 177 372 1943 2296 124 46.34 1.27 FBISE - Computer Section FEDERAL BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE AND SECONDARY EDUCATION, ISLAMABAD 2 RESULT GAZETTE OF SSC-II SUPPL. EXAMINATION 2018 ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THE GAZETTE Subjects EHE:I ESSENTIAL OF HOME ECONOMICS - I PST-II PAKISTAN STUDIES - II (HIC) AMD:I ART AND MODEL DRAWING - I EHE:II ESSENTIAL OF HOME ECONOMICS - II U-C:I URDU COMPULSORY - I AMD:I ART AND MODEL DRAWING - I (HIC) F-N:I FOOD AND NUTRITION - I U-C:I URDU COMPULSORY - I (HIC) AMD:II ART AND MODEL DRAWING - II F-N:II FOOD AND NUTRITION - II U-C:II URDU COMPULSORY - II AMD:II ART AND MODEL DRAWING - II (HIC) G-M:I MATHEMATICS (GEN.) - I U-C:II URDU COMPULSORY - II (HIC) ARB:I ARABIC - I G-M:II MATHEMATICS (GEN.) - II U-S URDU SALEES (IN LIEU OF URDU II) ARB:II ARABIC - II G-S:I GENERAL SCIENCE - I WEL:I WELDING (ARC & GAS) - I BIO:I BIOLOGY - I G-S:I GENERAL SCIENCE - I (HIC) WEL:II WELDING (ARC AND GAS) - II BIO:II BIOLOGY - II G-S:II GENERAL SCIENCE - II WWF:I WOOD WORKING AND FUR. -

Pakistan: Arrival and Departure

01-2180-2 CH 01:0545-1 10/13/11 10:47 AM Page 1 stephen p. cohen 1 Pakistan: Arrival and Departure How did Pakistan arrive at its present juncture? Pakistan was originally intended by its great leader, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, to transform the lives of British Indian Muslims by providing them a homeland sheltered from Hindu oppression. It did so for some, although they amounted to less than half of the Indian subcontinent’s total number of Muslims. The north Indian Muslim middle class that spearheaded the Pakistan movement found itself united with many Muslims who had been less than enthusiastic about forming Pak- istan, and some were hostile to the idea of an explicitly Islamic state. Pakistan was created on August 14, 1947, but in a decade self-styled field marshal Ayub Khan had replaced its shaky democratic political order with military-guided democracy, a market-oriented economy, and little effective investment in welfare or education. The Ayub experiment faltered, in part because of an unsuccessful war with India in 1965, and Ayub was replaced by another general, Yahya Khan, who could not manage the growing chaos. East Pakistan went into revolt, and with India’s assistance, the old Pakistan was bro- ken up with the creation of Bangladesh in 1971. The second attempt to transform Pakistan was short-lived. It was led by the charismatic Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who simultaneously tried to gain control over the military, diversify Pakistan’s foreign and security policy, build a nuclear weapon, and introduce an economic order based on both Islam and socialism. -

Pakistan: Social and Cultural Transformation in a Muslim Nation by Mohammad A

Book Review (Muhammad Aurang Zeb Mughal∗) Pakistan: Social and Cultural Transformation in a Muslim Nation by Mohammad A. Qadeer London and New York: Routledge, 2006 ISBN: 978-0-415-37566-5 Pages: 336, Price: £85 In post-colonial era, many non-western societies have set their own goals of development and they have been successful to an extent in achieving their objectives, therefore, according to Mohammad A. Qadeer the view that poor especially Muslim societies are socially stagnant and resistant to modernization is not justified. Pakistan is an important Muslim country with reference to its historical and geopolitical location. Despite of not having a high level of economic triumph Pakistan represents a model of culturally and socially dynamic country. Qadeer himself regards this book as a ‘contemporary social history’ of Pakistan that elaborates geography, history, religion, state, politics, economics, civil society and other institutions of Pakistani society in a historical and evolutionary perspective.1 Qadeer demonstrates the dynamicity of Pakistani culture through economic development and social change, and has given the demographic figures on urbanization, population growth and such related phenomena. The book specifically explains the topics like popular culture, ethnic groups and national identity, agrarian and industrial economy, family patterns, governance and civil society formation, and Islamic way of life. Even a new state emerged in the mid of 20th century, Pakistan’s history and culture can be traced thousand years back in the Indus Valley Civilization. The land of Pakistan has experienced the cultures of Aryans, Greeks, Arabs, Turks ∗ Ph.D. Scholar, Durham University, UK Book Review 147 especially Mughals, French, British and other foreigners either in the form of rulers, preachers or traders. -

Old Habits, New Consequences Old Habits, New Khalid Homayun Consequences Nadiri Pakistan’S Posture Toward Afghanistan Since 2001

Old Habits, New Consequences Old Habits, New Khalid Homayun Consequences Nadiri Pakistan’s Posture toward Afghanistan since 2001 Since the terrorist at- tacks of September 11, 2001, Pakistan has pursued a seemingly incongruous course of action in Afghanistan. It has participated in the U.S. and interna- tional intervention in Afghanistan both by allying itself with the military cam- paign against the Afghan Taliban and al-Qaida and by serving as the primary transit route for international military forces and matériel into Afghanistan.1 At the same time, the Pakistani security establishment has permitted much of the Afghan Taliban’s political leadership and many of its military command- ers to visit or reside in Pakistani urban centers. Why has Pakistan adopted this posture of Afghan Taliban accommodation despite its nominal participa- tion in the Afghanistan intervention and its public commitment to peace and stability in Afghanistan?2 This incongruence is all the more puzzling in light of the expansion of insurgent violence directed against Islamabad by the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), a coalition of militant organizations that are independent of the Afghan Taliban but that nonetheless possess social and po- litical links with Afghan cadres of the Taliban movement. With violence against Pakistan growing increasingly indiscriminate and costly, it remains un- clear why Islamabad has opted to accommodate the Afghan Taliban through- out the post-2001 period. Despite a considerable body of academic and journalistic literature on Pakistan’s relationship with Afghanistan since 2001, the subject of Pakistani accommodation of the Afghan Taliban remains largely unaddressed. Much of the existing literature identiªes Pakistan’s security competition with India as the exclusive or predominant driver of Pakistani policy vis-à-vis the Afghan Khalid Homayun Nadiri is a Ph.D. -

Pakistan- Party System

SUBJECT: POLITICAL SCIENCE VI COURSE: BA LLB SEMESTER V (NON-CBCS) TEACHER: MS. DEEPIKA GAHATRAJ MODULE II, PAKISTAN PARTY SYSTEM (i). The Awami National Party (ANP) is a left-wing, secular, Pashtun nationalist party, drawing its strength mainly from the Pashtun-majority areas of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) province. It is also active the urban areas of Sindh province and elsewhere. The party was officially formed in 1986 as a conglomeration of several left-leaning parties, but had existed in some form as far back as 1965, when Khan Abdul Wali Khan split from the existing National Awami Party. Khan was following in the political footsteps of Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan (Bacha Khan, popular known as the “Frontier Gandhi”), one of the most prominent nonviolent pro- independence figures under the British Raj. Today, the party is led by Asfandyar Wali Khan, Abdul Wali Khan's son. At the national level, the ANP has traditionally stood with the PPP, the only other major secular party operating across the country. 2008 was no different, and the ANP was one of the PPP's most stalwart allies in the previous government, with its 13 seats in the National Assembly backing the coalition throughout its five-year term in office. In the 2013 polls, however, the ANP will have to contend with high anti-incumbent sentiment in its stronghold of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, as a result of a lack of economic development and a deteriorating security situation. The ANP itself has borne the brunt of political violence in the province, with more than 750 ANP workers, activists and leaders killed by the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan in the last several years, according to the party's information secretary, Zahid Khan. -

A Political Biography of King Amanullah Khan

A POLITICAL BIOGRAPHY OF KING AMANULLAH KHAN DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF iJlajSttr of ^Ijiloioplip IN 3 *Kr HISTORY • I. BY MD. WASEEM RAJA UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF DR. R. K. TRIVEDI READER CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDU) 1996 J :^ ... \ . fiCC i^'-'-. DS3004 CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY r.u Ko„ „ S External ; 40 0 146 I Internal : 3 4 1 DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSTTY M.IGARH—202 002 fU.P.). INDIA 15 October, 1996 This is to certify that the dissertation on "A Political Biography of King Amanullah Khan", submitted by Mr. Waseem Raja is the original work of the candidate and is suitable for submission for the award of M.Phil, degree. 1 /• <^:. C^\ VVv K' DR. Rij KUMAR TRIVEDI Supervisor. DEDICATED TO MY DEAREST MOTHER CONTENTS CHAPTERS PAGE NO. Acknowledgement i - iii Introduction iv - viii I THE LAND AND THE PEOPLE 1-11 II HISTORICAL ANTECEDANTS 12 - 27 III AMANULLAH : EARLY DAYS AND FACTORS INFLUENCING HIS PERSONALITY 28-43 IV AMIR AMANULLAH'S ASSUMING OF POWER AND THE THIRD ANGLO-AFGHAN WAR 44-56 V AMIR AMANULLAH'S REFORM MOVEMENT : EVOLUTION AND CAUSES OF ITS FAILURES 57-76 VI THE KHOST REBELLION OF MARCH 1924 77 - 85 VII AMANULLAH'S GRAND TOUR 86 - 98 VIII THE LAST DAYS : REBELLION AND OUSTER OF AMANULLAH 99 - 118 IX GEOPOLITICS AND DIPLCMIATIC TIES OF AFGHANISTAN WITH THE GREAT BRITAIN, RUSSIA AND GERMANY A) Russio-Afghan Relations during Amanullah's Reign 119 - 129 B) Anglo-Afghan Relations during Amir Amanullah's Reign 130 - 143 C) Response to German interest in Afghanistan 144 - 151 AN ASSESSMENT 152 - 154 BIBLIOGRAPHY 155 - 174 APPENDICES 175 - 185 **** ** ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The successful completion of a work like this it is often difficult to ignore the valuable suggestions, advice and worthy guidance of teachers and scholars. -

Khushal Khan Khattak's Educational Philosophy

Khushal Khan Khattak’s Educational Philosophy Presented to: Department of Social Sciences Qurtuba University, Peshawar Campus Hayatabad, Peshawar In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Of Doctor of Philosophy in Education By Niaz Muhammad PhD Education, Research Scholar 2009 Qurtuba University of Science and Information Technology NWFP (Peshawar, Pakistan) In the name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful. ii Copyrights Niaz Muhammad, 2009 No Part of this Document may be reprinted or re-produced in any means, with out prior permission in writing from the author of this document. iii CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL DOCTORAL DISSERTATION This is to certify that the Doctoral Dissertation of Mr.Niaz Muhammad Entitled: Khushal Khan Khattak’s Educational Philosophy has been examined and approved for the requirement of Doctor of Philosophy degree in Education (Supervisor & Dean of the Social Science) Signature…………………………………. Qurtuba University, Peshawar Prof. Dr.Muhammad Saleem (Co-Supervisor) Signature…………………………………. Center of Pashto Language & Literature, Prof. Dr. Parvaiz Mahjur University of Peshawar. Examiners: 1. Prof. Dr. Saeed Anwar Signature…………………………………. Chairman Department of Education Hazara University, External examiner, (Pakistan based) 2. Name. …………………………… Signature…………………………………. External examiner, (Foreign based) 3. Name. ………………………………… Signature…………………………………. External examiner, (Foreign based) iv ABSTRACT Khushal Khan Khattak passed away about three hundred and fifty years ago (1613–1688). He was a genius, a linguist, a man of foresight, a man of faith in Al- Mighty God, a man of peace and unity, a man of justice and equality, a man of love and humanity, and a man of wisdom and knowledge. He was a multidimensional person known to the world as moralist, a wise chieftain, a great religious scholar, a thinker and an ideal leader of the Pushtoons. -

Kakaji Sanobar Hussain Mohmand an Everlasting Personality

TAKATOOT Issue 5Volume 3 20 January - June 2011 Kakaji Sanobar Hussain Mohmand An Everlasting Personality Dr. Hanif Khalil Abstract: Kakaji Sanobar Hussain Mohmand was a renowned intellectual and politician of the sub-continent among the pashtoon celebrities. He was a poet, critic, researcher, Journalist and translator of Pashto literature at a time. Apart from this he was a practical politician and a freedom fighter. Kakaji Sanobar played a vital role in the reawakening of the pashtoons as well as the other minorities against the British imperialism and the cruel and unjust policies of the Britishers in the sub continent. He used his journalistic abilities and his journal the monthly Aslam as well as his writings in prose and verses for achieving the targets to his real mission. For the fulfillment of this purpose he remained in jails for several years. He gave a lot of sacrifices, faces many hurdles and difficulties, but no one could remove him from his firm determination. In this paper the author has elaborated the major achievements and surveyed the practical steps and sacrifices of this legendary personality of the 20 th century. This paper is actually a tribute to Kakaji Sanobar Hussain the stalwart personality of pashtoon nation . I declare, that among the genius personalities of Pashtun nation, after khushal Khan Khattak, Kakaji Sanobar Hussain is a personality which could be accepted as a multi-dimensional celebrity. For the acceptance of that declaration, I would say that Kakaji was not only a great man but also a great Politician, Writer, Journalist and a Social Worker simultaneously. -

Pakistan History Culture and Goverment.Pdf

Pakistan: History, Culture, and Government Teaching Guide Nigel Smith Contents Introduction to the Teaching Guide iv Introduction (Student’s Book) 7 Part 1 The Cultural and Historical Background of the Pakistan Movement Chapter 1 The Decline of the Mughal Empire 9 Chapter 2 The Influence of Islam 11 Chapter 3 The British in India 14 Chapter 4 Realism and Confidence 24 Part 2 The Emergence of Pakistan, 1906-47 Chapter 5 Muslims Organize 27 Chapter 6 Towards Pakistan: 1922-40 36 Chapter 7 War and Independence 41 Part 3 Nationhood: 1947-88 Chapter 8 The New Nation 47 Chapter 9 The Government of Pakistan 52 Chapter 10 The 1970s 60 Part 4 Pakistan and the World Chapter 11 Pakistan and Asia 66 Chapter 12 Pakistan and the rest of the world 71 Chapter 13 Pakistan: 1988 to date 77 Revision exercises 86 Sample Examination Paper 92 Sample Mark Scheme 94 1 iii Introduction to the Teaching Guide History teachers know very well the importance and pleasure of learning history. Teaching the history of your own nation is particularly satisfying. This history of Pakistan, and the examination syllabus that it serves, will prove attractive to your pupils. Indeed it would be a strange young person who did not find a great deal to intrigue and stimulate them. So your task should be made all the easier by their natural interest in the events and struggles of their forebears. This Teaching Guide aims to provide detailed step-by-step support to the teachers for improving students’ understanding of the events and factors leading to the creation of Pakistan and its recent history and to prepare students for success in the Cambridge O level and Cambridge IGCSE examinations. -

The Road to Afghanistan

Introduction Hundreds of books—memoirs, histories, fiction, poetry, chronicles of military units, and journalistic essays—have been written about the Soviet war in Afghanistan. If the topic has not yet been entirely exhausted, it certainly has been very well documented. But what led up to the invasion? How was the decision to bring troops into Afghanistan made? What was the basis for the decision? Who opposed the intervention and who had the final word? And what kind of mystical country is this that lures, with an almost maniacal insistence, the most powerful world states into its snares? In the nineteenth and early twentieth century it was the British, in the 1980s it was the Soviet Union, and now America and its allies continue the legacy. Impoverished and incredibly backward Afghanistan, strange as it may seem, is not just a normal country. Due to its strategically important location in the center of Asia, the mountainous country has long been in the sights of more than its immediate neighbors. But woe to anyone who arrives there with weapon in hand, hoping for an easy gain—the barefoot and illiterate Afghans consistently bury the hopes of the strange foreign soldiers who arrive along with battalions of tanks and strategic bombers. To understand Afghanistan is to see into your own future. To comprehend what happened there, what happens there continually, is to avoid great tragedy. One of the critical moments in the modern history of Afghanistan is the period from April 27, 1978, when the “April Revolution” took place in Kabul and the leftist People’s Democratic Party seized control of the country, until December 27, 1979, when Soviet special forces, obeying their “international duty,” eliminated the ruling leader and installed 1 another leader of the same party in his place. -

Biographies of Main Political Leaders of Pakistan

Biographies of main political leaders of Pakistan INCUMBENT POLITICAL LEADERS ASIF ALI ZARDARI President of Pakistan since 2008 Asif Ali Zardari is the eleventh and current President of Pa- kistan. He is the Co-Chairman of the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), a role he took on following the demise of his wife, Benazir Bhutto. Zardari rose to prominence in 1987 after his marriage to Benazir Bhutto, holding cabinet positions in both the 1990s PPP governments, and quickly acquired a reputation for corrupt practices. He was arrested in 1996 after the dismissal of the second government of Bena- zir Bhutto, and remained incarcerated for eight years on various charges of corruption. Released in 2004 amid ru- mours of reconciliation between Pervez Musharraf and the PPP, Zardari went into self-imposed exile in Dubai. He re- turned in December 2007 following Bhutto’s assassination. In 2008, as Co-Chairman of PPP he led his party to victory in the general elections. He was elected as President on September 6, 2008, following the resignation of Pervez Musharraf. His early years in power were characterised by widespread unrest due to his perceived reluctance to reinstate the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court (who had been dismissed during the Musharraf imposed emergency of 2007). However, he has also overseen the passage of the 18th Amendment to the Constitution which effectively www.presidentofpakistan.gov.pk reduced presidential powers to that of a ceremonial figure- Asif Ali Zardari, President head. He remains, however, a highly controversial figure and continues to be dogged by allegations of corruption. Mohmmad government as Minister of Housing and Public Works.