First Human Infection Case of Monkey B Virus Identified in China, 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Novel Therapeutics for Epstein–Barr Virus

molecules Review Novel Therapeutics for Epstein–Barr Virus Graciela Andrei *, Erika Trompet and Robert Snoeck Laboratory of Virology and Chemotherapy, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Rega Institute for Medical Research, KU Leuven, 3000 Leuven, Belgium; [email protected] (E.T.); [email protected] (R.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +32-16-321-915 Academic Editor: Stefano Aquaro Received: 15 February 2019; Accepted: 4 March 2019; Published: 12 March 2019 Abstract: Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) is a human γ-herpesvirus that infects up to 95% of the adult population. Primary EBV infection usually occurs during childhood and is generally asymptomatic, though the virus can cause infectious mononucleosis in 35–50% of the cases when infection occurs later in life. EBV infects mainly B-cells and epithelial cells, establishing latency in resting memory B-cells and possibly also in epithelial cells. EBV is recognized as an oncogenic virus but in immunocompetent hosts, EBV reactivation is controlled by the immune response preventing transformation in vivo. Under immunosuppression, regardless of the cause, the immune system can lose control of EBV replication, which may result in the appearance of neoplasms. The primary malignancies related to EBV are B-cell lymphomas and nasopharyngeal carcinoma, which reflects the primary cell targets of viral infection in vivo. Although a number of antivirals were proven to inhibit EBV replication in vitro, they had limited success in the clinic and to date no antiviral drug has been approved for the treatment of EBV infections. We review here the antiviral drugs that have been evaluated in the clinic to treat EBV infections and discuss novel molecules with anti-EBV activity under investigation as well as new strategies to treat EBV-related diseases. -

Where Do We Stand After Decades of Studying Human Cytomegalovirus?

microorganisms Review Where do we Stand after Decades of Studying Human Cytomegalovirus? 1, 2, 1 1 Francesca Gugliesi y, Alessandra Coscia y, Gloria Griffante , Ganna Galitska , Selina Pasquero 1, Camilla Albano 1 and Matteo Biolatti 1,* 1 Laboratory of Pathogenesis of Viral Infections, Department of Public Health and Pediatric Sciences, University of Turin, 10126 Turin, Italy; [email protected] (F.G.); gloria.griff[email protected] (G.G.); [email protected] (G.G.); [email protected] (S.P.); [email protected] (C.A.) 2 Complex Structure Neonatology Unit, Department of Public Health and Pediatric Sciences, University of Turin, 10126 Turin, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] These authors contributed equally to this work. y Received: 19 March 2020; Accepted: 5 May 2020; Published: 8 May 2020 Abstract: Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), a linear double-stranded DNA betaherpesvirus belonging to the family of Herpesviridae, is characterized by widespread seroprevalence, ranging between 56% and 94%, strictly dependent on the socioeconomic background of the country being considered. Typically, HCMV causes asymptomatic infection in the immunocompetent population, while in immunocompromised individuals or when transmitted vertically from the mother to the fetus it leads to systemic disease with severe complications and high mortality rate. Following primary infection, HCMV establishes a state of latency primarily in myeloid cells, from which it can be reactivated by various inflammatory stimuli. Several studies have shown that HCMV, despite being a DNA virus, is highly prone to genetic variability that strongly influences its replication and dissemination rates as well as cellular tropism. In this scenario, the few currently available drugs for the treatment of HCMV infections are characterized by high toxicity, poor oral bioavailability, and emerging resistance. -

WHO | World Health Organization

WHO/CDS/CSR/99.1 Report of the meeting of the Ad Hoc Committee on Orthopoxvirus Infections. Geneva, Switzerland, 14-15 January 1999 World Health Organization Department of Communicable Disease Surveillance and Response This document has been downloaded from the WHO/CSR Web site. The original cover pages and lists of participants are not included. See http://www.who.int/emc for more information. © World Health Organization This document is not a formal publication of the World Health Organization (WHO), and all rights are reserved by the Organization. The document may, however, be freely reviewed, abstracted, reproduced and translated, in part or in whole, but not for sale nor for use in conjunction with commercial purposes. The views expressed in documents by named authors are solely the responsibility of those authors. The mention of specific companies or specific manufacturers' products does no imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Contents Introduction 1 Recent monkeypox outbreaks in the Democratic Republic of Congo 1 Review of the report of the 1994 Ad Hoc Committee on Orthopoxvirus Infections 2 Work in WHO Collaborating Centres 3 Analysis and sequencing of variola virus genomes 3 Biosecurity and physical security of WHO collaborating laboratories 4 Smallpox vaccine stocks and production 4 Deliberate release of smallpox virus 4 Survey of WHO Member States latest position on destruction of variola virus 4 Recommendations 5 List of Participants 6 Page i REPORT OF THE MEETING OF THE AD HOC COMMITTEE ON ORTHOPOXVIRUS INFECTIONS Geneva, Switzerland 14-15 January 1999 Introduction Dr Lindsay Martinez, Director, Communicable Disease Surveillance and Response (CSR), welcomed participants and opened the meeting on behalf of the Director-General of WHO, Dr G.H. -

A Tale of Two Viruses: Coinfections of Monkeypox and Varicella Zoster Virus in the Democratic Republic of Congo

Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg., 104(2), 2021, pp. 604–611 doi:10.4269/ajtmh.20-0589 Copyright © 2021 by The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene A Tale of Two Viruses: Coinfections of Monkeypox and Varicella Zoster Virus in the Democratic Republic of Congo Christine M. Hughes,1* Lindy Liu,2,3 Whitni B. Davidson,1 Kay W. Radford,4 Kimberly Wilkins,1 Benjamin Monroe,1 Maureen G. Metcalfe,3 Toutou Likafi,5 Robert Shongo Lushima,6 Joelle Kabamba,7 Beatrice Nguete,5 Jean Malekani,8 Elisabeth Pukuta,9 Stomy Karhemere,9 Jean-Jacques Muyembe Tamfum,9 Emile Okitolonda Wemakoy,5 Mary G. Reynolds,1 D. Scott Schmid,4 and Andrea M. McCollum1 1Poxvirus and Rabies Branch, Division of High-Consequence Pathogens and Pathology, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia; 2Bacterial Special Pathogens Branch, Division of High-Consequence Pathogens and Pathology, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia; 3Infectious Diseases Pathology Branch, Division of High-Consequence Pathogens and Pathology, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia; 4Viral Vaccine Preventable Diseases Branch, Division of Viral Diseases, National Center for Immunizations and Respiratory Diseases, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia; 5Kinshasa School of Public Health, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo; 6Ministry of Health, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo; 7U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo; 8Department of Biology, University of Kinshasa, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo; 9Institut National de Recherche Biomedicale, ´ Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo Abstract. -

Risk Groups: Viruses (C) 1988, American Biological Safety Association

Rev.: 1.0 Risk Groups: Viruses (c) 1988, American Biological Safety Association BL RG RG RG RG RG LCDC-96 Belgium-97 ID Name Viral group Comments BMBL-93 CDC NIH rDNA-97 EU-96 Australia-95 HP AP (Canada) Annex VIII Flaviviridae/ Flavivirus (Grp 2 Absettarov, TBE 4 4 4 implied 3 3 4 + B Arbovirus) Acute haemorrhagic taxonomy 2, Enterovirus 3 conjunctivitis virus Picornaviridae 2 + different 70 (AHC) Adenovirus 4 Adenoviridae 2 2 (incl animal) 2 2 + (human,all types) 5 Aino X-Arboviruses 6 Akabane X-Arboviruses 7 Alastrim Poxviridae Restricted 4 4, Foot-and- 8 Aphthovirus Picornaviridae 2 mouth disease + viruses 9 Araguari X-Arboviruses (feces of children 10 Astroviridae Astroviridae 2 2 + + and lambs) Avian leukosis virus 11 Viral vector/Animal retrovirus 1 3 (wild strain) + (ALV) 3, (Rous 12 Avian sarcoma virus Viral vector/Animal retrovirus 1 sarcoma virus, + RSV wild strain) 13 Baculovirus Viral vector/Animal virus 1 + Togaviridae/ Alphavirus (Grp 14 Barmah Forest 2 A Arbovirus) 15 Batama X-Arboviruses 16 Batken X-Arboviruses Togaviridae/ Alphavirus (Grp 17 Bebaru virus 2 2 2 2 + A Arbovirus) 18 Bhanja X-Arboviruses 19 Bimbo X-Arboviruses Blood-borne hepatitis 20 viruses not yet Unclassified viruses 2 implied 2 implied 3 (**)D 3 + identified 21 Bluetongue X-Arboviruses 22 Bobaya X-Arboviruses 23 Bobia X-Arboviruses Bovine 24 immunodeficiency Viral vector/Animal retrovirus 3 (wild strain) + virus (BIV) 3, Bovine Bovine leukemia 25 Viral vector/Animal retrovirus 1 lymphosarcoma + virus (BLV) virus wild strain Bovine papilloma Papovavirus/ -

Fact Sheet: Basic Information About Monkeypox

MONKEYPOX FACT SHEET Basic Information about Monkeypox Monkeypox: An Emerging Infectious Disease in North America Monkeypox is a rare viral disease that is found mostly in the rainforest countries of central and west Africa. The disease is called “monkeypox” because it was first discovered in laboratory monkeys in 1958. Blood tests of animals in Africa later found evidence of monkeypox infection in various rodent species. The virus that causes monkeypox was recovered from an African squirrel, which may be the natural host. Laboratory studies showed that the virus could also infect rats, mice, and rabbits. In 1970, monkeypox was identified as the cause of a rash illness in humans in remote African locations. In early June 2003, monkeypox was reported among several residents in the United States who became ill after having contact with sick pet prairie dogs. This is the first evidence of community-acquired monkeypox in the United States. Cause of Monkeypox The disease is caused by Monkeypox virus, which belongs to the orthopoxvirus group of viruses. Other orthopoxviruses that can cause infection in humans include variola (smallpox), vaccinia (used in smallpox vaccine), and cowpox viruses. Signs and Symptoms In humans, the signs and symptoms of monkeypox are similar to those of smallpox, but usually milder. Unlike smallpox, monkeypox causes swollen lymph nodes. The incubation period for monkeypox is about 12 days.The illness begins with fever, headache, muscle aches, backache, swollen lymph nodes, a general feeling of discomfort, and exhaustion. Within 1 to 3 days (sometimes longer) after onset of fever, the patient develops a papular rash (i.e., raised bumps), often first on the face but sometimes initially on other parts of the body. -

Herpes B Virus: Implications in Lab Workers, Travelers, and Pet Owners

Herpes B Virus: Implications in Lab Workers, Travelers, and Pet Owners Presenter: Kevin Johnson DO, MPH Chief Resident Harvard OEMR Discussant: Thomas Winters, MD, FACOEM Chief Medical Officer and Principal Partner OEHN Objectives 1. Discuss how Herpes B infection is transmitted 2. List symptoms of Herpes B infection in humans 3. Describe vaccination and treatment options for Herpes B. The Case of a Lab Worker • S: . 53 y/o clinician/researcher at a local lab went to MGH with fever, HA, and rigors 3/27/12. Notes being scratched by a research monkey (Macaque sp) 9 days prior on dorsum of L hand. Washed the wound for few minutes but did not report the injury. Negative for neck pain, or difficulty with concentration. • O: . PE: Scar longitudinal between 3rd and 4th MC L hand 3 cm. Negative for vesicular lesions, erythema, signs of infection, or rashes • Labs: . LP's performed weekly with Herpes B negative on PCR . Elevated WBC’s seen on CBC • Imaging: . 2 MRI’s were normal On week 3 LP again performed with PCR of CSF positive for Herpes B and serology with Ab (+) A: Diagnosed with Meningoencephelitis 2/2 to Herpes B infection Background (History) First documented case of B-virus infection in 1932 when a researcher was bitten on the hand by an apparently healthy rhesus macaque and died of progressive encephalomyelitis 15 days later. Background • Transmission via contact with oral-secretions . Direct (bite, scratch, contact with body fluid or tissue) . Indirect (contaminated fomite e.g., needle puncture or cage scratch) . Human-to-human transmission has been documented in one case Macaque Attack!!!! What About Travelers? • B virus prevalent in macaques native to SE Asia. -

Cross-Species Antiviral Activity of Goose Interferons Against Duck

viruses Article Cross-Species Antiviral Activity of Goose Interferons against Duck Plague Virus Is Related to Its Positive Self-Feedback Regulation and Subsequent Interferon Stimulated Genes Induction Hao Zhou 1,†, Shun Chen 1,2,3,*,†, Qin Zhou 1, Yunan Wei 1, Mingshu Wang 1,2,3, Renyong Jia 1,2,3, Dekang Zhu 2,3, Mafeng Liu 1, Fei Liu 3, Qiao Yang 1,2,3, Ying Wu 1,2,3, Kunfeng Sun 1,2,3, Xiaoyue Chen 2,3 and Anchun Cheng 1,2,3,* 1 Institute of Preventive Veterinary Medicine, Sichuan Agricultural University, No. 211 Huimin Road, Wenjiang District, Chengdu 611130, China; [email protected] (H.Z.); [email protected] (Q.Z.); [email protected] (Y.W.); [email protected] (M.W.); [email protected] (R.J.); [email protected] (M.L.); [email protected] (Q.Y.); [email protected] (Y.W.); [email protected] (K.S.) 2 Avian Disease Research Center, College of Veterinary Medicine, Sichuan Agricultural University, Chengdu 611130, China; [email protected] (D.Z.); [email protected] (X.C.) 3 Key Laboratory of Animal Disease and Human Health of Sichuan Province, Sichuan Agricultural University, Chengdu 611130, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.C.); [email protected] (A.C.); Tel.: +86-028-86291482 † These authors contributed equally to this work. Academic Editor: Curt Hagedorn Received: 23 May 2016; Accepted: 12 July 2016; Published: 18 July 2016 Abstract: Interferons are a group of antiviral cytokines acting as the first line of defense in the antiviral immunity. Here, we describe the antiviral activity of goose type I interferon (IFNα) and type II interferon (IFNγ) against duck plague virus (DPV). -

Ev20n1p53.Pdf (663.1Kb)

SEROLOGIC SCREENING FOR CYTOMEGALOVIRUS, RUBELLA VIRUS, HERPESSIMPLEX VIRUS, HEPATITIS B VIRUS, AND Z-DXOl?~snIlA GONDII IN TWO URBAN POPULATIONS OF PREGNANT WOMEN IN CHILE1 Pablo Vzlzl;2 Jorge Toves-Pereyra, 3 Sergio Stagno, 4 Francisco Gonzhfez,’ Enrique Donoso, G Chades A. Allford, 7 Zimara Hirsch, 8 and Luk Rodtiguezg I NTRODUCTION these agents represent naturally acquired infections. There are only a few reports Although the prevalence of concerning the epidemiology of congeni- congenital and perinatal infections is tal and perinatal infections in Chile (l- high, however, it is.unclear whether their $&In general, these reports show that incidence during the childbearing years the prevalences of infection with most of (and hence their potential to cause fetal the causative agents are high and that disease) is different from that observed in most infections are acquired at an early communities such as those in developed age. Since vaccinations against cytomeg- countries where lower prevalences are the alovirus (CMV), herpes simplex virus rule. Therefore, in order to help assess (HSV), and Toxopl’asma gondii have not the importance of CMV, HSV, rubella, yet been introduced, high prevalences of HBV, and ToxopLasmagondii as causesof z 2 < ’ This article is also being published in Spanish in the 4 Department of Pediatrics, University of Alabama. Bir- 2 BoLefin de /a Oficina Sanitankz Panameticana, 99(5), mingham. Alabama, United States. % 1985. The work reported here was supported by Grant s Division of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Dr. Sotero de1 x ‘4 LHZ503Q from the Pan American Health Organita- Rio Hospital, Puente Alto, Chile. u 6 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology. -

Viral Hepatitis B: Introduction

Viral Hepatitis B: Introduction “Viral hepatitis," refers to infections that affect the liver and are caused by viruses. It is a major public health issue in the United States and worldwide. Not only does viral hepatitis carry a high morbidity, but it also stresses medical resources and can have severe economic consequences. The majority of all viral hepatitis cases are preventable. Viral hepatitis includes five distinct disease entities, which are caused by at least five different viruses. Hepatitis A and hepatitis B (infectious and serum hepatitis, respectively) are considered separate diseases and both can be diagnosed by a specific serologic test. Hepatitis C and E comprise a third category, each a distinct type, with Hepatitis C parenterally transmitted, and hepatitis E enterically transmitted. Hepatitis D, or delta hepatitis, is another distinct virus that is dependent upon hepatitis B infection. This form of hepatitis may occur as a super-infectionin a hepatitis B carrier or as a co-infection in an individual with acute hepatitis B. Hepatitis viruses most often found in the United States include A, B, C, and D. Because fatality from hepatitis is relatively low, mortality figures are a poor indicator of the actual incidence of these diseases. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that approximately 400,000–600,000 people were infected with viral hepatitis during the decade of the 1990s. Hepatitis plagued mankind as early as the fifth century BC. It was referenced in early biblical literature and described as occurring in outbreaks, especially during times of war. Toward the end of the nineteenth century, hepatitis was thought to occur as a result of infection of the hepatic parenchyma. -

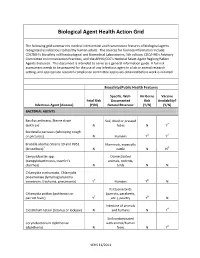

Biological Agent Health Action Grid

Biological Agent Health Action Grid The following grid summarizes medical intervention and transmission features of biological agents recognized as infectious to healthy human adults. The sources for foonote information include: CDC/NIH’s Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories, 5th edition; CDC/HHS’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; and the APHIS/CDC’s National Select Agent Registry/Select Agents Exclusion. This document is intended to serve as a general information guide. A full risk assessment needs to be prepared for the use of any infectious agent in a lab or animal research setting, and appropriate research compliance committee approvals obtained before work is initiated. Biosafety/Public Health Features Specific, Well- Air-Borne Vaccine Fetal Risk Documented Risk Availability? Infectious Agent (disease) (Y/N) Natural Reservoir (Y/N) (Y/N) BACTERIAL AGENTS Bacillus anthracis, Sterne strain Soil, dried or pressed (anthrax)1 N hides N Y2 Bordetella pertussis (whooping cough or pertussis) N Humans Y3 Y4 Brucella abortus Strains 19 and RB51 Mammals, especially (brucellosis)5 N cattle N N6 Campylobacter spp. Domesticated (campylobacteriosis, traveler's animals, rodents, diarrhea) N birds N N Chlamydia trachomatis, Chlamydia pneumoniae (lymphogranuloma venereum, trachoma, pneumonia) Y7 Humans Y8 N Psittacine birds Chlamydia psittaci (psittacosis or (parrots, parakeets, parrott fever) Y7 etc.), poultry Y8 N Intestine of animals Clostridium tetani (tetanus or lockjaw) N and humans N Y4 Soil contaminated Corynebacterium diphtheriae with animal/human (diphtheria) N feces N Y4 VEHS 11/2011 Specific, Well- Air-Borne Vaccine Fetal Risk Documented Risk Availability? Infectious Agent (disease) (Y/N) Natural Reservoir (Y/N) (Y/N) Francisella tularensis, subspecies Wild animals, esp. -

Identi Cation of Campylobacter Jejuni and Chlamydia Psittaci from Cockatiel

Identication of Campylobacter Jejuni and Chlamydia Psittaci From cockatiel (Nymphicus Hollandicus) Using Metagenomics Si-Hyeon Kim Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency Yong-Kuk Kwon Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency Choi-Kyu Park Kyungpook National University Hye-Ryoung Kim ( [email protected] ) Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency Research Article Keywords: pet birds, cockatiel, metagenomics, chlamydiosis, campylobacteriosis, recombination, metaSPAdes Posted Date: June 1st, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-563212/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/16 Abstract Background In July 2015, the carcasses of 11 cockatiels were submitted for disease diagnosis to the Avian Disease Division of the Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency of Korea. The cockatiels, which appeared dehydrated and underweight, had exhibited severe diarrhea and 22% mortality over 2 weeks. Traditional diagnosis did not reveal the causes of these symptoms. Methods We conducted metagenomics analysis on intestines and livers from the dead cockatiels using Illumina high-throughput sequencing. To obtain more accurate and longer contigs, which are required for further genetic characterization, we compared the results of three de novo assembly tools (metaSPAdes, MEGAHIT, and IDBA-UD). Results Sequence reads of Campylobacter jejuni (C. jejuni) and Chlamydia psittaci (C. psittaci) were present in most of the cockatiel samples. Either of these bacteria could cause the reported symptoms in psittaciformes. metaSPAdes (ver.3.14.1) identied the 1152 bp aA gene of C. jejuni and the 1096 bp ompA gene of C. psittaci. Genetic analysis revealed that aA of C. jejuni was recombinant between C.