Changing Security Situation in South Asia and Development of CPEC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pakdef E-Reporter Vol I No. 1 October-November 2006

Pakdef E-Reporter Vol I No. 1 October-November 2006 Editorial: Syed Ahmed [email protected] Submit Contributions: [email protected] Usman Shabbir [email protected] H Khan [email protected] Feedback: [email protected] Copyright ©1998-2006, PakDef.info. All rights reserved. The reproduction of the contents of this website & its newsletter (Pakdef E- Reporter) in whole or in part, in any form or medium without the express written permission of PakDef is prohibited. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ____________________________________________________________ 3 Bunker News ________________________________________________________________ 6 The First Cyber War – Part 1 __________________________________________________ 10 Gwadar: Competition From All Sides____________________________________________ 12 Multan Conference Jan. 1972__________________________________________________ 14 The Birth of Pakistan's Nuclear Weapons Program.________________________________ 14 End of the line for the once proud Hangor class ___________________________________ 19 India’s Claim on Kashmir Has No Justification ___________________________________ 25 Rise of the Falcon: Future of PAF ______________________________________________ 35 INTRODUCTION elcome to PakDef E-Reporter, an illuminating new publication put out by Pakistan Military Consortium (PMC) and www.pakdef.info. PMC is devoted towards W disseminating accurate information on Pakistan’s army, air force, navy and strategic command. We hope you will find here facts concerning Pakistan not commonly available elsewhere. However, first a disclaimer: despite the focus on Pakistani military and geo-strategic issues, neither this publication, nor PMC, nor www.pakdef.info have anything to do with The Government of Pakistan, its military establishment or any civil agency. PakDef E-Reporter is purely a private initiative by individuals from diverse backgrounds, who have an interest in military and geo-strategic issues relating to Pakistan. -

Energy Trade in South Asia Opportunities and Challenges

Energy Trade in South Asia in South Asia: Energy Trade Opportunities and Challenges The South Asia Regional Energy Study was completed as an important component of the regional technical assistance project Preparing the Energy Sector Dialogue and South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation Energy Center Capacity Development. It involved examining regional energy trade opportunities among all the member states of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation. The study provides interventions to improve regional energy cooperation in different timescales, including specific infrastructure projects which can be implemented during Opportunities and Challenges these periods. ENERGY TRADE IN SOUTH ASIA About the Asian Development Bank OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES ADB’s vision is an Asia and Pacific region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its developing member countries reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their people. Despite the region’s many successes, it remains home to two-thirds of the world’s poor: 1.8 billion people who live on less than $2 a day, with 903 million struggling on less than $1.25 a day. ADB is committed to reducing poverty through inclusive economic growth, environmentally sustainable growth, and regional integration. Based in Manila, ADB is owned by 67 members, including 48 from the region. Its main instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue, loans, equity investments, guarantees, grants, and technical assistance. Sultan Hafeez Rahman Priyantha D. C. Wijayatunga Herath Gunatilake P. N. Fernando Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines www.adb.org Printed on recycled paper. Printed in the Philippines ENERGY TRADE IN SOUTH ASIA OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES Sultan Hafeez Rahman Priyantha D. -

December 16-31, 2019 September 16-30, 2020

December 16-31, 2019 September 16-30, 2020 SeSe 1 Table of Contents 1: September 16, 2020………………………………….……………………….…03 2: September 17, 2020………………………………….……………………….....08 3: September 18, 2020…………………………………………………………......10 4: September 19, 2020………………………………………………...…................15 5: September 20, 2020………………………………………………..…..........….. 18 6: September 21, 2020………………………………………………………….…..20 7: September 22, 2020………………………………………………………………25 8: September 23, 2020……………………………………….………………….......26 9: September 24, 2020……………………………………………...……………….34 10: September 25, 2020…………………………………………………….............39 11: September 26, 2020………………………………………………………….….45 12: September 27, 2020……………………………………………………………. 50 13: September 28, 2020…………………………………………………………..…54 14: September 29, 2020………………………………………………………..….....57 15: September 30, 2020……………………………………………….………..…... 64 Data collected and compiled by Rabeeha Safdar, Mahnoor Raza, Anosh and Muqaddas Sanaullah Disclaimer: PICS reproduce the original text, facts and figures as appear in the newspapers and is not responsible for its accuracy. 2 September 16, 2020 Pakistan Observer Rashakai SEZ to set new direction for industrialization: Fareena The Board of Investment on Tuesday said that the Rashakai, Special Economic Zone would set a new direction for the modern industrialization in Pakistan and bring huge Foreign Direct Investment in the country. Recently the Pakistan and China signed the development agreement of the Rashakai SEZ under China Pakistan Economic Corridor‟s to promote the Ease of Doing Business -

Produced by the Human Security Centre Lead Author

1 Human Security Centre – Written evidence (AFG0019) Produced by the Human Security Centre Lead Author: Simon Schofield, Senior Fellow, In consultation with Rohullah Yakobi, Associate Fellow 2 1 Table of Contents 2. Executive Summary .............................................................................5 3. What is the Human Security Centre?.....................................................10 4. Geopolitics and National Interests and Agendas......................................11 Islamic Republic of Pakistan ...................................................................11 Historical Context...............................................................................11 Pakistan’s Strategy.............................................................................12 Support for the Taliban .......................................................................13 Afghanistan as a terrorist training camp ................................................16 Role of military aid .............................................................................17 Economic interests .............................................................................19 Conclusion – Pakistan .........................................................................19 Islamic Republic of Iran .........................................................................20 Historical context ...............................................................................20 Iranian Strategy ................................................................................23 -

Taajudin's Diary

Taajudin’s Diary Account of a Muslim author who accompanied Guru Nanak from Makkah to Baghdad By Sant Syed Prithipal Singh ne’ Mushtaq Hussain Shah (1902-1969) Edited & Translated By: Inderjit Singh Table of Contents Foreword................................................................................................. 7 When Guru Nanak Appeared on the World Scene ............................. 7 Guru Nanak’s Travel ............................................................................ 8 Guru Nanak’s Mission Was Outright Universal .................................. 9 The Book Story .................................................................................. 12 Acquaintance with Syed Prithipal Singh ....................................... 12 Discovery by Sardar Mangal Singh ................................................ 12 Professor Kulwant Singh’s Treatise ............................................... 13 Generosity of Mohinder Singh Bedi .............................................. 14 A Significant Book ............................................................................. 15 Recommendation ............................................................................. 16 Foreword - Sant Prithipal Singh ji Syed, My Father .............................. 18 ‘The Lion of the Lord took to the trade of the Fox’ – Translator’s Note .............................................................................................................. 20 About Me – Preface by Sant Syed Prithipal Singh ............................... -

Indian Initiatives for Maritime Dominance: Pakistan's Options and Response

THE INSTITUTE OF STRATEGIC STUDIES ISLAMABAD, PAKISTAN Registered under societies registration Act No. XXI of 1860 The Institute of Strategic Studies was founded in 1973. It is a non- profit, autonomous research and analysis centre, designed for promoting an informed public understanding of strategic and related issues, affecting international and regional security. In addition to publishing a quarterly journal and a monograph series, the ISSI organises talks, workshops, seminars and conferences on strategic and allied disciplines and issues. BOARD OF GOVERNORS Chairman Ambassador Khalid Mahmood MEMBERS Dr. Tariq Banuri Prof. Dr. Muhammad Ali Chairman, Higher Education Vice Chancellor Commission, Islamabad Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad Ex-Officio Ex-Officio Foreign Secretary Finance Secretary Ministry of Foreign Affairs Ministry of Finance Islamabad Islamabad Ambassador Seema Illahi Baloch Ambassador Mohammad Sadiq Ambassador Aizaz Ahmad Chaudhry Director General Institute of Strategic Studies, Islamabad (Member and Secretary Board of Governors) Indian Initiatives for Maritime Dominance: Pakistan's Options and Response Muhammad Abbas Hassan * July 2019 * Muhammad Abbas Hassan is Research Associate, Institute of Strategic Studies Islamabad. EDITORIAL TEAM Editor-in-Chief : Ambassador Aizaz Ahmad Chaudhry Director General, ISSI Editor : Najam Rafique Director Research Publication Officer : Azhar Amir Malik Composed and designed by : Syed Muhammad Farhan Title Cover designed by : Sajawal Khan Afridi Published by the Director General on behalf of the Institute of Strategic Studies, Islamabad. Publication permitted vide Memo No. 1481-77/1181 dated 7-7-1977. ISSN. 1029-0990 Articles and monographs published by the Institute of Strategic Studies can be reproduced or quoted by acknowledging the source. Views expressed in the article are of the author and do not represent those of the Institute. -

Fizzy Drinks and Sufi Music: Abida Parveen in Coke Studio Pakistan

Fizzy Drinks and Sufi Music: Abida Parveen in Coke Studio Pakistan By Zainub Beg A Thesis Submitted to Saint Mary’s University, K’jipuktuk/Halifax, Nova Scotia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Theology and Religious Studies. December 2020, Halifax, Nova Scotia Copyright Zainub Beg, 2020 Approved: Dr. Syed Adnan Hussain Supervisor Approved: Dr. Reem Meshal Examiner Approved: Dr. Sailaja Krishnamurti Reader Date: December 21, 2020 1 Fizzy Drinks and Sufi Music: Abida Parveen in Coke Studio Pakistan by Zainub Beg Abstract Abida Parveen, often referred to as the Queen of Sufi music, is one of the only female qawwals in a male-dominated genre. This thesis will explore her performances for Coke Studio Pakistan through the lens of gender theory. I seek to examine Parveen’s blurring of gender, Sufism’s disruptive nature, and how Coke Studio plays into the two. I think through the categories of Islam, Sufism, Pakistan, and their relationship to each other to lead into my analysis on Parveen’s disruption in each category. I argue that Parveen holds a unique position in Pakistan and Sufism that cannot be explained in binary terms. December 21, 2020 2 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................... 1 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................ 3 Chapter One: Introduction .................................................................................. -

The Very Foundation, Inauguration and Expanse of Sufism: a Historical Study

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 6 No 5 S1 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy September 2015 The Very Foundation, Inauguration and Expanse of Sufism: A Historical Study Dr. Abdul Zahoor Khan Ph.D., Head, Department of History & Pakistan Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences, Faculty Block #I, First Floor, New Campus Sector#H-10, International Islamic University, Islamabad-Pakistan; Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Muhammad Tanveer Jamal Chishti Ph.D. Scholar-History, Department of History &Pakistan Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences, Faculty Block #I, First Floor New Campus, Sector#H-10, International Islamic University, Islamabad-Pakistan; Email: [email protected] Doi:10.5901/mjss.2015.v6n5s1p382 Abstract Sufism has been one of the key sources to disseminate the esoteric aspects of the message of Islam throughout the world. The Sufis of Islam claim to present the real and original picture of Islam especially emphasizing the purity of heart and inner-self. To realize this objective they resort to various practices including meditation, love with fellow beings and service for mankind. The present article tries to explore the origin of Sufism, its gradual evolution and culmination. It also seeks to shed light on the characteristics of the Sufis of the different periods or generations as well as their ideas and approaches. Moreover, it discusses the contributions of the different Sufi Shaykhs as well as Sufi orders or Silsilahs, Qadiriyya, Suhrwardiyya, Naqshbandiyya, Kubraviyya and particularly the Chishtiyya. Keywords: Sufism, Qadiriyya, Chishtiyya, Suhrwardiyya, Kubraviyya-Shattariyya, Naqshbandiyya, Tasawwuf. 1. Introduction Sufism or Tasawwuf is the soul of religion. -

January 2016 NEWS COVERAGE PERIOD JANUARY 25TH to JANUARY 31ST, 2016 PROTESTERS DEMAND PROPER SHARE for GB in CPEC Dawn, January 25Th, 2016

January 2016 NEWS COVERAGE PERIOD JANUARY 25TH TO JANUARY 31ST, 2016 PROTESTERS DEMAND PROPER SHARE FOR GB IN CPEC Dawn, January 25th, 2016 ISLAMABAD: A large number of people belonging to Gilgit-Baltistan, including members of the area’s legislative assembly, on Sunday held a protest demonstration in front of National Press Club demanding proper share in China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). They also demanded that GB should be declared the fifth province of Pakistan so that the people of the backward area could get their basic rights. The protest was organised by the Youth of Gilgit-Baltistan, a non-political platform representing the youth of the area. Speaking on the occasion, member of the legislative assembly, Kacho Imtiaz, said people of GB could not get their basic rights even after 68 years. “We had passed a resolution in the legislative assembly that there should be three hubs of CPEC in GB but only one station is being given to us for loading and unloading of goods. Moreover, no industrial zone is being set up in GB,” he complained. Another MLA, Haji Rizwan, said basic rights should be ensured for the people of GB. “Moreover, the government of PML-N should implement the National Action Plan (NAP) in its letter and spirit and take action against terrorists instead of using the law for its own benefits,” he said. The protesters also demanded that Gilgit-Baltistan should get representation in the National Assembly, Senate and the National Finance Commission. Talking to Dawn, chairman of the GB Youth’s coordination committee, Hasnain Kazmi, said the government should give basic rights to the people of GB. -

China-Pakistan Economic Corridor

U A Z T m B PEACEWA RKS u E JI Bulunkouxiang Dushanbe[ K [ D K IS ar IS TA TURKMENISTAN ya T N A N Tashkurgan CHINA Khunjerab - - ( ) Ind Gilgit us Sazin R. Raikot aikot l Kabul 1 tro Mansehra 972 Line of Con Herat PeshawarPeshawar Haripur Havelian ( ) Burhan IslamabadIslamabad Rawalpindi AFGHANISTAN ( Gujrat ) Dera Ismail Khan Lahore Kandahar Faisalabad Zhob Qila Saifullah Quetta Multan Dera Ghazi INDIA Khan PAKISTAN . Bahawalpur New Delhi s R du Dera In Surab Allahyar Basima Shahadadkot Shikarpur Existing highway IRAN Nag Rango Khuzdar THESukkur CHINA-PAKISTANOngoing highway project Priority highway project Panjgur ECONOMIC CORRIDORShort-term project Medium and long-term project BARRIERS ANDOther highway IMPACT Hyderabad Gwadar Sonmiani International boundary Bay . R Karachi s Provincial boundary u d n Arif Rafiq I e nal status of Jammu and Kashmir has not been agreed upon Arabian by India and Pakistan. Boundaries Sea and names shown on this map do 0 150 Miles not imply ocial endorsement or 0 200 Kilometers acceptance on the part of the United States Institute of Peace. , ABOUT THE REPORT This report clarifies what the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor actually is, identifies potential barriers to its implementation, and assesses its likely economic, socio- political, and strategic implications. Based on interviews with federal and provincial government officials in Pakistan, subject-matter experts, a diverse spectrum of civil society activists, politicians, and business community leaders, the report is supported by the Asia Center at the United States Institute of Peace (USIP). ABOUT THE AUTHOR Arif Rafiq is president of Vizier Consulting, LLC, a political risk analysis company specializing in the Middle East and South Asia. -

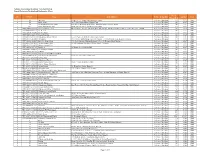

Unpaid Preference Dividend and Redemption Money.Xlsx

Pakistan International Container Terminal Limited Unpaid Preference Dividend and Redemption Money No. of S.No Folio No Name Last Address Nature of Amount Amount Year Shares Held 1 55 Dr-Kanta H.No 1417-C, Nawan Tak Mohalla, Larkana Preference Dividend 141 23.27 2005 2 58 Zakia Aslam 96-C, Aziz Shahed Road, Sialkot Cantt Preference Dividend 141 23.27 2005 3 78 Mr Abdul Ghaffar Begawala Flat No- 16 Rangoon Wala House, Dhoraji Colony, Karachi 74800. Preference Dividend 141 23.27 2005 4 247 Malik Mohammad Afzal House No 715, Street-103 G-9/4, Islamabad Preference Dividend 141 23.27 2005 5 CDC-00067-01937C Maqsood Hanif (Ah3) Madina Palace Plot No 147, 4 Th Floor Flat No 401, C P Barar H Society Block, 7 & 8 Karachi = 74800 Preference Dividend 141 23.27 2005 6 CDC-00299-02623C M A Jalal - Preference Dividend 141 23.27 2005 7 CDC-00489-02109C M.Irfan Brohi - Preference Dividend 141 23.27 2005 8 CDC-00596-02451C Khalid Mukhtar - Preference Dividend 141 23.27 2005 9 CDC-01388-03165C Muhammad Anwar Sheikh 17 - Z, Phase - Iii, D.H.A.,Lahore Cantt. Lahore Preference Dividend 141 23.27 2005 10 CDC-01412-05769C Irshadullah C/O Karachi Bulk Storage Terminal Ltd 60/1-A,Oil Instalation Area, Keamari, Karachi. Preference Dividend 141 23.27 2005 11 CDC-01552-08543C Saeed A. Khan (Rwp) C/O Shell Pakistan (Multan Regional Office) 75-D Qasim Road Multan Preference Dividend 141 23.27 2005 12 CDC-01552-22742C Ayesha Sarfraz (Khr) 122-D, Shadman Residency, Clifton, Block 2, Karachi. -

Role of Persians at the Mughal Court: a Historical

ROLE OF PERSIANS AT THE MUGHAL COURT: A HISTORICAL STUDY, DURING 1526 A.D. TO 1707 A.D. PH.D THESIS SUBMITTED BY, MUHAMMAD ZIAUDDIN SUPERVISOR: PROF. DR. MUNIR AHMED BALOCH IN THE AREA STUDY CENTRE FOR MIDDLE EAST & ARAB COUNTRIES UNIVERSITY OF BALOCHISTAN QUETTA, PAKISTAN. FOR THE FULFILMENT OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY 2005 DECLARATION BY THE CANDIDATE I, Muhammad Ziauddin, do solemnly declare that the Research Work Titled “Role of Persians at the Mughal Court: A Historical Study During 1526 A.D to 1707 A.D” is hereby submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy and it has not been submitted elsewhere for any Degree. The said research work was carried out by the undersigned under the guidance of Prof. Dr. Munir Ahmed Baloch, Director, Area Study Centre for Middle East & Arab Countries, University of Balochistan, Quetta, Pakistan. Muhammad Ziauddin CERTIFICATE This is to certify that Mr. Muhammad Ziauddin has worked under my supervision for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. His research work is original. He fulfills all the requirements to submit the accompanying thesis for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Dr. Munir Ahmed Research Supervisor & Director Area Study Centre For Middle East & Arab Countries University of Balochistan Quetta, Pakistan. Prof. Dr. Mansur Akbar Kundi Dean Faculty of State Sciences University of Balochistan Quetta, Pakistan. d DEDICATED TO THE UNFORGETABLE MEMORIES OF LATE PROF. MUHAMMAD ASLAM BALOCH OF HISTORY DEPARTMENT UNIVERSITY OF BALOCHISTAN, QUETTA PAKISTAN e ACKNOWLEDGMENT First of all I must thank to Almighty Allah, who is so merciful and beneficent to all of us, and without His will we can not do anything; it is He who guide us to the right path, and give us sufficient knowledge and strength to perform our assigned duties.