Chapter 16 Epistemic Faith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

新成立/ 註冊及已更改名稱的公司名單list of Newly Incorporated

This is the text version of a report with Reference Number "RNC063" and entitled "List of Newly Incorporated /Registered Companies and Companies which have changed Names". The report was created on 01-02-2016 and covers a total of 2985 related records from 25-01-2016 to 31-01-2016. 這是報告編號為「RNC063」,名稱為「新成立 / 註冊及已更改名稱的公司名單」的純文字版報告。這份報告在 2016 年 2 月 1 日建立,包含從 2016 年 1 月 25 日到 2016 年 1 月 31 日到共 2985 個相關紀錄。 Each record in this report is presented in a single row with 6 data fields. Each data field is separated by a "Tab". The order of the 6 data fields are "Sequence Number", "Current Company Name in English", "Current Company Name in Chinese", "C.R. Number", "Date of Incorporation / Registration (D-M-Y)" and "Date of Change of Name (D-M-Y)". 每個紀錄會在報告內被設置成一行,每行細分為 6 個資料。 每個資料會被一個「Tab 符號」分開,6 個資料的次序為「順序編號」、「現用英文公司名稱」、「現用中文公司名稱」、「公司註冊編號」、「成立/註 冊日期(日-月-年)」、「更改名稱日期(日-月-年)」。 Below are the details of records in this report. 以下是這份報告的紀錄詳情。 1. 21Vianet Global Limited 2175966 26-01-2016 2. 3 Point Limited 三禾有限公司 2334566 25-01-2016 3. 33 Blanc Group Limited 2334707 25-01-2016 4. 3B Enterprises Limited 2335606 27-01-2016 5. 4iCreative Limited 2336607 29-01-2016 6. 5A INTERNATIONAL LIMITED 2335580 27-01-2016 7. 90 Day Korean Limited 2336804 29-01-2016 8. A & I Pharmacare Co., Limited 2336361 29-01-2016 9. A LEE Logistics Limited 阿里物流有限公司 2335622 27-01-2016 10. A Roentgen 3T Medical Imaging Limited 2335595 27-01-2016 11. -

Purpose and Variation in Religious Records of the Tang

tang religious records nathan woolley The Many Boats to Yangzhou: Purpose and Variation in Religious Records of the Tang n Tang China during the seventh century, the official Dou Dexuan I 竇德玄 (598–666) was once travelling on government business to Yangzhou when he met an otherworldly being who warned Dou of his impending death. Fortunately for Dou, this fate was avoided and he went on become one of the highest officials in the empire. Four texts agree on this core narrative but differ in their descrip- tions and details. The four texts — an item from an otherwise lost Dao- ist collection, a work describing the lineage of Shangqing Daoism, an anecdote attributed to a Buddhist collection of evidential miracles, and an entry in the compilation of a late-Tang Daoist master — display contrasting priorities in how they depict religious experience and prac- tice. They all date to within a period of around two centuries, but their interrelations remain unclear. The contrasts, however, provide a win- dow for examining the purposes that lay behind the creation of certain types of religious text, as well as contemporary perceptions of religious culture. Although not sharply divergent in terms of format, there are in fact differences among them that point to fundamental processes in the production of narrative and religious texts in China. Through the history of Chinese writing and texts, a single nar- rative may occur in different guises. It may simply be that a writer imbued an existing narrative with a changed focus and thereby pro- duced a different rendering. Alternatively, a tale could be updated to fit new social circumstances and expectations, or new developments in genre and performance. -

Resurgence of Indigenous Religion in China Fan Lizhu and Chen

Resurgence of Indigenous Religion in China Fan Lizhu and Chen Na1 Many scholars have observed in recent years that religion and spirituality are resurgent around the world. Contrary to the predictions of sociologists and others that modern society will eventually become completely secularized, it appears that human beings are engaged in a wide range of religious and/or spiritual experiences, disciplines, beliefs, practices, etc. that were virtually unimaginable two decades ago. In this chapter we seek to provide evidence that traditional (also known as primal, traditional, folk, indigenous, etc.) religions are also involved in this revitalization, not just Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, and other religions. We will focus on the People’s Republic of China as an extended case study of the widespread return to religion and spirituality around the world. Some of our discussion will be based on findings from our own research in China in both urban and rural areas. During the last thirty years many people in mainland China have rediscovered and revitalized their earlier religious and ritual practices. Kenneth Dean estimates that one to two million village temples have been rebuilt or restored across China, and ritual traditions long thought lost are now being re-invented and celebrated in many of these temples.1 This very rough figure of well over a million village temples does not include the tens of thousands of large-scale Buddhist monasteries and temples, Daoist monasteries and temples, Islamic mosques, and Christian churches (Catholic or Protestant) that have been rebuilt or restored over the past three decades. Recent anthropological 1 Fan Lizhu, Professor of Sociology, Fudan University. -

CR1981-12.Pdf

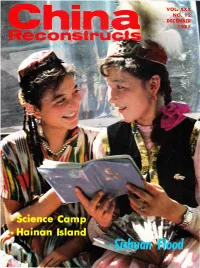

Morning on the grasslands. ll'ang Xitrntin '+ 8i!. _,1 f\9 i\ FOUNDER: SOONG CHING LING (MME. SUN YAT.SENI llse3.1e8ll. PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE ClllNA wELFARE tNSflTUTE tN ENGLISH, FRENCH, spANlsH, ARAHC, GERMAN, poRIUGUESE AND cHlNEsE VOt. XXX No. 12 DECEMBER 1981 Articles of the M onth CONTENTS ln Memory of the 1911 Revolution Noti,onwide celebrotions mork the 70th onni- Politics versory'of ol the Hu Yoo' ln Commemoration: the 70th Anniversary of the 1911 bong the Centrol the Bevolution 4 Committee ex on peocelul reun mother' Economy iond, ond invi visit the Diversilying the Rural Economy 11 moinlond. Poge 4 Our Brigade's Uphill Struggle 1B Herdsmen on the 'Roof of the World 46 ;& Hainan, the Treasure lsland (l) 56 After the Deluge China's Prepared Food lndustry h4 Losses ore severe ofter Culture ond Art summer floods in Sichuon province, but A People's Cultural Center in Dalian 41 people ore rebuilding Pursuit 44 with couroge, ingenuity The Road l've Traveled 45 ond hope. PoEe 7 Husband-and-Wife Design Team ta The Wanfotang Grottoes 71 Medicine,/Sports Lives Mentolly lll New Lives, New Hope for the Mentallv lll 19 New for the Beijing lnternational Marathon Race 66 Progroms medicotion, occupotionol theropy ond sociolizotion in Shonghoi Across the Lond help potients into normol life ond ovoid Alter the Deiuge 7 relopses. Poge 19 A Famous Beiling Dish 32 Beijing's New Subway Network 52 Herdsmen on the Friendship 'Roof of the World' Journalists Make Friendship Visit to Thailand Scientific arosslonds Notionolities monogemenl in Yushu New Turning Point in Tibet 29 Tibeton Autonomous Future Scientists Spread Their Wings Summer Prefecture the highest - postorol lond- in Chino Science Camp for National Minority Youth 34 brought prosper' Science -ftrosity lo hordy locol Puee 46 China Launches Three Satellites with a Single Rocket 22 herdsmen. -

The Revival of Tiantai Buddhism in the Late Ming: on the Thought of Youxi Chuandeng 幽溪傳燈 (1554-1628)

The Revival of Tiantai Buddhism in the Late Ming: On the Thought of Youxi Chuandeng 幽溪傳燈 (1554-1628) Yungfen Ma Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2011 © 2011 Yungfen Ma All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The Revival of Tiantai Buddhism in the Late Ming: On the Thought of Youxi Chuandeng 幽溪傳燈 (1554-1628) Yungfen Ma This dissertation is a study of Youxi Chuandeng’s (1554-1628) transformation of “Buddha-nature includes good and evil,” also known as “inherent evil,” a unique idea representing Tiantai’s nature-inclusion philosophy in Chinese Buddhism. Focused on his major treatise On Nature Including Good and Evil, this research demonstrates how Chuandeng, in his efforts to regenerate Tiantai, incorporated the important intellectual themes of the late Ming, especially those found in the Śūraṃgama Sūtra. In his treatise, Chuandeng systematically presented his ideas on doctrinal classification, the principle of nature-inclusion, and the practice of the Dharma-gate of inherent evil. Redefining Tiantai doctrinal classification, he legitimized the idea of inherent evil to be the highest Buddhist teaching and proved the superiority of Buddhism over Confucianism. Drawing upon the notions of pure mind and the seven elements found in the Śūraṃgama Sūtra, he reinterpreted nature-inclusion and the Dharma-gate of inherent evil emphasizing inherent evil as pure rather than defiled. Conversely, he reinterpreted the Śūraṃgama Sūtra by nature-inclusion. Chuandeng incorporated Confucianism and the Śūraṃgama Sūtra as a response to the dominating thought of his day, this being the particular manner in which previous Tiantai thinkers upheld, defended and spread Tiantai. -

Buddhism and Taoism in the White Snake by Jerry James

Buddhism and Taoism in The White Snake by Jerry James “In the end, only three things matter: how much you loved, how gently you lived, and how gracefully you let go of things not meant for you.” This is a Buddhist saying, even though the sometime between the 4th and 6th centuries Buddha never said it. But it does resonate BCE. He was a scion of the royal family of the with Mary Zimmerman’s version of the Tale of warrior caste and was raised as a prince. the White Snake. Echoing the religious Edward Conze relates: practices of China itself, Zimmerman draws on various traditions to tell the story in her own At the age of 29, Siddhartha left his palace way. to meet his subjects. Despite his father's efforts to hide from him the sick, aged and In a similar manner, even though many of us suffering, Siddhartha was said to have had never heard of the White Snake before seen an old man. When his charioteer The Rogue announced its production, the explained to him that all people grew old, milieu in which the story originated and the prince went on further trips beyond continues to live has resonated with Western the palace. On these he encountered a culture for over 500 years, sometimes in diseased man, a decaying corpse, and an surprising ways, as we shall see. ascetic. These depressed him, and he initially strove to overcome aging, This tale was first fixed in tangible form in sickness, and death by living the life of an 1624, when Feng Menglong collected it in his ascetic. -

Curriculum Vitae Xunqiang

Curriculum Vitae Xunqiang Yin 1. Basic Information Full Name: Xunqiang Yin Nationality: Chinese Job Title: Physical Oceanographer Research Area ocean dynamics and modeling Education level: PhD The First Institute of Oceanography, Affiliation: Ministry of Natural Resources, China Address: No.6 Xian-Xia-Ling Road, Qingdao 266061 China Email: [email protected] 2. Work and Education Experience Education Sep.2008~Jul. 2015: Ph.D. Physical Oceanography, The Ocean University of China, China Sep.2002~Jul. 2005: M.S. Physical Oceanography, The First Institute of Oceanography, State Oceanic Administration, China Sep.1997~Jul. 2001: B.S. Physical Oceanography, The Ocean University of China, China Work Experience Dec. 2011~present: The First Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources, China, Associate Researcher Sep. 2006~Dec. 2011: The First Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources, China, Research Assistant Jun. 2005~Sep. 2006: Princeton University, USA, Visiting scholar/ Research Assistant Jul. 2001~Jun. 2005: The First Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources, China, Research Fellow. 3. Selected Publications 1) ZHAO Yiding, YIN Xunqiang, SONG Yajuan, QIAO Fangli. 2019. Seasonal prediction skills of FIO-ESM for North Pacific sea surface temperature and precipitation. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 38(1):5-12 2) Zhao Yiding,Yin Xunqiang, Song Yajuan, etal. Effect of wave-induced mixing on sea surface temperature seasonal prediction in the North Pacific in 2016 [J]. Haiyang Xuebao, 2019,41(3):52-61, doi: 10.3969/j.issn.0253-4193.2019.03.006(in Chinese) 3) Xunqiang Yin, Junqiang Shi, Fangli Qiao. Evaluation on surface current observing network of high frequency ground wave radars in the Gulf of Thailand, Ocean Dynamics, 2018, 68:575–587. -

Interim Report 2019 1 Contents

Important Notice I. The Board, the Supervisory Committee and the directors, supervisors and senior management of the Company collectively and individually accept full responsibility for the truthfulness, accuracy and completeness of the information contained in this interim report and confirms that there is no false information, misleading statements or material omissions in this interim report. II. The Directors were present at the 25th meeting of the seventh session of the Board, among whom, Ms. Cheng Ning (vice chairperson of the Board) attended the meeting by telephone, Mr. Chu Xiaoping (independent non-executive director) was unable to attend the meeting due to business and had appointed Mr. Jiang Wenqi (independent non-executive director) to attend the meeting and vote on his behalf. III. Mr. Li Chuyuan (chairperson of the Board), Mr. Li Hong (executive director and general manager) and Ms. Yao Zhizhi (deputy controller of finance and head of the finance department) individually accept responsibility for ensuring the authenticity and completeness of the financial reports contained in this interim report. IV. After consideration, the Board did not recommend payment of interim dividends for the six months ended 30 June 2019 nor propose any increase in share capital from the capitalization of capital reserve. V. The financial report of the Group and the Company for the Reporting Period was prepared in accordance with the China Accounting Standards for Business Enterprises, which was unaudited. VI. Forward-looking statements such as plans for the future and development strategy described in this report do not constitute any actual commitment of the Company to investors. Investors are advised to pay attention to any investment risk. -

Supplements for Pets • Chinese Herbal Folk Tales • Ginseng and Alzheimer’S • 2008 Herbal Market Report

HerbalGram 82 • May – July 2009 82 • May HerbalGram Supplements for Pets • Chinese Herbal Folk Tales • Ginseng and Alzheimer’s • 2008 Herbal Market Report Supplements The Journal of the American Botanical Council Number 82 | May – July 2009 for Pets • Chinese Herbal Folk Tales • Rhodiola for Fatigue • Ginseng and Alzheimer’s • 2008 Herbal Market Report • Ginseng and Alzheimer’s Fatigue • Rhodiola for Tales • Chinese Herbal Folk Pets for Supplements • St. John’s Wort and Depression Wort • St. John’s for Pets Chinese Herbal US/CAN $6.95 Folk Tales www.herbalgram.org Herb Sales Rise in 2008 www.herbalgram.org www.herbalgram.org 2009 HerbalGram 82 | 1 STILL HERBAL AFTER ALL THESE YEARS Celebrating 30 Years of Supporting America’s Health The year 2009 marks Herb Pharm’s 30th anniversary as a leading producer and distributor of therapeutic herbal extracts. During this time we have continually emphasized the importance of using the best quality certified organically cultivated and sustainably-wildcrafted herbs to produce our herbal healthcare products. This is why we created the “Pharm Farm” – our certified organic herb farm, and the “Plant Plant” – our modern, FDA-audited production facility. It is here that we integrate the centuries-old, time-proven knowledge and wisdom of traditional herbal medicine with the herbal sciences and technology of the 21st Century. Equally important, Herb Pharm has taken a leadership role in social and environmental responsibility through projects like our use of the Blue Sky renewable energy program, our farm’s streams and Supporting America’s Health creeks conservation program, and the Botanical Sanctuary program Since 1979 whereby we research and develop practical methods for the conser- vation and organic cultivation of endangered wild medicinal herbs. -

Report Title Xi, Baikang (Um 1979) Bibliographie : Autor Xi, Chen

Report Title - p. 1 of 235 Report Title Xi, Baikang (um 1979) Bibliographie : Autor 1979 [Maupassant, Guy de]. Mobosang duan pian xiao shuo xuan du. Mobosang ; Xi Baikang. (Shanghai : Shanghai yi wen chu ban she, 1979). [Übersetzung ausgewählter Kurzgeschichten von Maupassant]. [WC] Xi, Chen (um 1923) Bibliographie : Autor 1923 [Russell, Bertrand]. Luosu lun wen ji. Luosu zhu ; Yang Duanliu, Xi Chen, Yu Yuzhi, Zhang Wentian, Zhu Pu yi. Vol. 1-2. (Shanghai : Shang wu yin shu guan, 1923). (Dong fang wen ku ; 44). [Enthält] : E guo ge ming de li lun ji shi ji. Übersetzung von Russell, Bertrand. The practice and theory of Bolshevism. (London : Allen & Unwin, 1920). She hui zhu yi yu zi you zhu yi. Hu Yuzhi yi. Übersetzung von Russell, Bertrand. Socialism and liberal ideals. In : Living age ; no 306 (July 10, 1920). Wei kai fa guo zhi gong ye. Yang Duanliu yi. Übersetzung von Russell, Bertrand. Industry in undeveloped countries. In : Atlantic monthly ; 127 (June 1921). Xian jin hun huan zhuang tai zhi yuan yin. Übersetzung von Russell, Bertrand. Causes of present chaos. In : The prospects of industrial civilization. (London : Allen & Unwin, 1923). Zhongguo guo min xing de ji ge te dian. Yu Zhi [Hu Yuzhi] yi. Übersetzung von Russell, Bertrand. Some traits in the Chinese character. In : Atlantic monthly ; 128 (Dec. 1921). Zhongguo zhi guo ji di wei. Zhang Wentian yi. [WC,Russ3] Xi, Chu (um 1920) Bibliographie : Autor 1920 [Whitman, Walt]. Huiteman zi you shi xuan yi. Xi Chu yi. In : Ping min jiao yu ; no 20 (March 1920). [Selected translations of Whitman's poems of freedom]. -

Universal Gate Chapter on Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva

The Lotus Sutra’s Universal Gate Chapter on Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva 妙法蓮華經觀世音菩薩普門品 Fo Guang Shan International Translation Center © 2016 Fo Guang Shan International Translation Center The Lotus Sutra’s Universal Gate Chapter on Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva Published by Fo Guang Shan International Translation Center 3456 Glenmark Drive Hacienda Heights, CA 91745 U.S.A. 妙法蓮華經觀世音菩薩普門品 Tel: (626) 330-8361 / (626) 330-8362 Fax: (626) 330-8363 www.fgsitc.org Protected by copyright under the terms of the International Copyright Union; all rights reserved. Except for fair use in book reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced for any reason by any means, including any method of photographic reproduction, without permission of the publisher. Printed in Taiwan. 目 錄 Table of Contents 楊枝淨水讚 2 Praise of Holy Water 3 開經偈 4 Sutra Opening Verse 5 妙法蓮華經 The Lotus Sutra’s Universal Gate Chapter 觀世音菩薩普門品 6 on Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva 7 般若波羅蜜多心經 62 Heart Sutra 63 千手千眼無礙大悲心陀羅尼 70 Dharani of Great Compassion 70 三皈依 76 Triple Refuge 77 迴向偈 78 Dedication of Merit 79 Glossary 80 Yang Zhi Jing Shui Zan Praise of Holy Water 楊 枝 淨 水 讚 Yang Zhi Jing Shui Bian Sa San Qian 楊 枝 淨 水 遍 灑 三 千 With willow twigs, may the holy water be sprinkled on the three thousand realms. Xing Kong Ba De Li Ren Tian 性 空 八 德 利 人 天 May the nature of emptiness and eight virtues benefit heaven and earth. Fu Shou Guang Zeng Yan 福 壽 廣 增 延 May good fortune and long life both be enhanced Mie Zui Xiao Qian and extended. -

Chinese Folk Religion

Chinese folk religion: The '''Chinese folk religion''' or '''Chinese traditional religion''' ( or |s=中国民间宗教 or 中国民间信 仰|p=Zhōngguó mínjiān zōngjiào or Zhōngguó mínjiān xìnyăng), sometimes called '''Shenism''' (pinyin+: ''Shénjiào'', 神教),refn|group=note| * The term '''Shenism''' (神教, ''Shénjiào'') was first used in 1955 by anthropologist+ Allan J. A. Elliott, in his work ''Chinese Spirit-Medium Cults in Singapore''. * During the history of China+ it was named '''Shendao''' (神道, ''Shéndào'', the "way of the gods"), apparently since the time of the spread of Buddhism+ to the area in the Han period+ (206 BCE–220 CE), in order to distinguish it from the new religion. The term was subsequently adopted in Japan+ as ''Shindo'', later ''Shinto+'', with the same purpose of identification of the Japanese indigenous religion. The oldest recorded usage of ''Shindo'' is from the second half of the 6th century. is the collection of grassroots+ ethnic+ religious+ traditions of the Han Chinese+, or the indigenous religion of China+.Lizhu, Na. 2013. p. 4. Chinese folk religion primarily consists in the worship of the ''shen+'' (神 "gods+", "spirit+s", "awarenesses", "consciousnesses", "archetype+s"; literally "expressions", the energies that generate things and make them thrive) which can be nature deities+, city deities or tutelary deities+ of other human agglomerations, national deities+, cultural+ hero+es and demigods, ancestor+s and progenitor+s, deities of the kinship. Holy narratives+ regarding some of these gods are codified into the body of Chinese mythology+. Another name of this complex of religions is '''Chinese Universism''', especially referring to its intrinsic metaphysical+ perspective. The Chinese folk religion has a variety of sources, localised worship forms, ritual and philosophical traditions.