Purpose and Variation in Religious Records of the Tang

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Laozi Zhongjing)

A Study of the Central Scripture of Laozi (Laozi zhongjing) Alexandre Iliouchine A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts, Department of East Asian Studies McGill University January 2011 Copyright Alexandre Iliouchine © 2011 ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements......................................................................................... v Abstract/Résumé............................................................................................. vii Conventions and Abbreviations.................................................................... viii Introduction..................................................................................................... 1 On the Word ―Daoist‖............................................................................. 1 A Brief Introduction to the Central Scripture of Laozi........................... 3 Key Terms and Concepts: Jing, Qi, Shen and Xian................................ 5 The State of the Field.............................................................................. 9 The Aim of This Study............................................................................ 13 Chapter 1: Versions, Layers, Dates............................................................... 14 1.1 Versions............................................................................................. 15 1.1.1 The Transmitted Versions..................................................... 16 1.1.2 The Dunhuang Version........................................................ -

The Daoist Tradition Also Available from Bloomsbury

The Daoist Tradition Also available from Bloomsbury Chinese Religion, Xinzhong Yao and Yanxia Zhao Confucius: A Guide for the Perplexed, Yong Huang The Daoist Tradition An Introduction LOUIS KOMJATHY Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 175 Fifth Avenue London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10010 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com First published 2013 © Louis Komjathy, 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Louis Komjathy has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury Academic or the author. Permissions Cover: Kate Townsend Ch. 10: Chart 10: Livia Kohn Ch. 11: Chart 11: Harold Roth Ch. 13: Fig. 20: Michael Saso Ch. 15: Fig. 22: Wu’s Healing Art Ch. 16: Fig. 25: British Taoist Association British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: 9781472508942 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Komjathy, Louis, 1971- The Daoist tradition : an introduction / Louis Komjathy. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4411-1669-7 (hardback) -- ISBN 978-1-4411-6873-3 (pbk.) -- ISBN 978-1-4411-9645-3 (epub) 1. -

新成立/ 註冊及已更改名稱的公司名單list of Newly Incorporated

This is the text version of a report with Reference Number "RNC063" and entitled "List of Newly Incorporated /Registered Companies and Companies which have changed Names". The report was created on 01-02-2016 and covers a total of 2985 related records from 25-01-2016 to 31-01-2016. 這是報告編號為「RNC063」,名稱為「新成立 / 註冊及已更改名稱的公司名單」的純文字版報告。這份報告在 2016 年 2 月 1 日建立,包含從 2016 年 1 月 25 日到 2016 年 1 月 31 日到共 2985 個相關紀錄。 Each record in this report is presented in a single row with 6 data fields. Each data field is separated by a "Tab". The order of the 6 data fields are "Sequence Number", "Current Company Name in English", "Current Company Name in Chinese", "C.R. Number", "Date of Incorporation / Registration (D-M-Y)" and "Date of Change of Name (D-M-Y)". 每個紀錄會在報告內被設置成一行,每行細分為 6 個資料。 每個資料會被一個「Tab 符號」分開,6 個資料的次序為「順序編號」、「現用英文公司名稱」、「現用中文公司名稱」、「公司註冊編號」、「成立/註 冊日期(日-月-年)」、「更改名稱日期(日-月-年)」。 Below are the details of records in this report. 以下是這份報告的紀錄詳情。 1. 21Vianet Global Limited 2175966 26-01-2016 2. 3 Point Limited 三禾有限公司 2334566 25-01-2016 3. 33 Blanc Group Limited 2334707 25-01-2016 4. 3B Enterprises Limited 2335606 27-01-2016 5. 4iCreative Limited 2336607 29-01-2016 6. 5A INTERNATIONAL LIMITED 2335580 27-01-2016 7. 90 Day Korean Limited 2336804 29-01-2016 8. A & I Pharmacare Co., Limited 2336361 29-01-2016 9. A LEE Logistics Limited 阿里物流有限公司 2335622 27-01-2016 10. A Roentgen 3T Medical Imaging Limited 2335595 27-01-2016 11. -

Resurgence of Indigenous Religion in China Fan Lizhu and Chen

Resurgence of Indigenous Religion in China Fan Lizhu and Chen Na1 Many scholars have observed in recent years that religion and spirituality are resurgent around the world. Contrary to the predictions of sociologists and others that modern society will eventually become completely secularized, it appears that human beings are engaged in a wide range of religious and/or spiritual experiences, disciplines, beliefs, practices, etc. that were virtually unimaginable two decades ago. In this chapter we seek to provide evidence that traditional (also known as primal, traditional, folk, indigenous, etc.) religions are also involved in this revitalization, not just Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, and other religions. We will focus on the People’s Republic of China as an extended case study of the widespread return to religion and spirituality around the world. Some of our discussion will be based on findings from our own research in China in both urban and rural areas. During the last thirty years many people in mainland China have rediscovered and revitalized their earlier religious and ritual practices. Kenneth Dean estimates that one to two million village temples have been rebuilt or restored across China, and ritual traditions long thought lost are now being re-invented and celebrated in many of these temples.1 This very rough figure of well over a million village temples does not include the tens of thousands of large-scale Buddhist monasteries and temples, Daoist monasteries and temples, Islamic mosques, and Christian churches (Catholic or Protestant) that have been rebuilt or restored over the past three decades. Recent anthropological 1 Fan Lizhu, Professor of Sociology, Fudan University. -

CR1981-12.Pdf

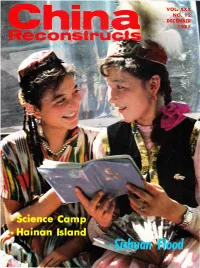

Morning on the grasslands. ll'ang Xitrntin '+ 8i!. _,1 f\9 i\ FOUNDER: SOONG CHING LING (MME. SUN YAT.SENI llse3.1e8ll. PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE ClllNA wELFARE tNSflTUTE tN ENGLISH, FRENCH, spANlsH, ARAHC, GERMAN, poRIUGUESE AND cHlNEsE VOt. XXX No. 12 DECEMBER 1981 Articles of the M onth CONTENTS ln Memory of the 1911 Revolution Noti,onwide celebrotions mork the 70th onni- Politics versory'of ol the Hu Yoo' ln Commemoration: the 70th Anniversary of the 1911 bong the Centrol the Bevolution 4 Committee ex on peocelul reun mother' Economy iond, ond invi visit the Diversilying the Rural Economy 11 moinlond. Poge 4 Our Brigade's Uphill Struggle 1B Herdsmen on the 'Roof of the World 46 ;& Hainan, the Treasure lsland (l) 56 After the Deluge China's Prepared Food lndustry h4 Losses ore severe ofter Culture ond Art summer floods in Sichuon province, but A People's Cultural Center in Dalian 41 people ore rebuilding Pursuit 44 with couroge, ingenuity The Road l've Traveled 45 ond hope. PoEe 7 Husband-and-Wife Design Team ta The Wanfotang Grottoes 71 Medicine,/Sports Lives Mentolly lll New Lives, New Hope for the Mentallv lll 19 New for the Beijing lnternational Marathon Race 66 Progroms medicotion, occupotionol theropy ond sociolizotion in Shonghoi Across the Lond help potients into normol life ond ovoid Alter the Deiuge 7 relopses. Poge 19 A Famous Beiling Dish 32 Beijing's New Subway Network 52 Herdsmen on the Friendship 'Roof of the World' Journalists Make Friendship Visit to Thailand Scientific arosslonds Notionolities monogemenl in Yushu New Turning Point in Tibet 29 Tibeton Autonomous Future Scientists Spread Their Wings Summer Prefecture the highest - postorol lond- in Chino Science Camp for National Minority Youth 34 brought prosper' Science -ftrosity lo hordy locol Puee 46 China Launches Three Satellites with a Single Rocket 22 herdsmen. -

Transforming the Void

iii Transforming the Void Embryological Discourse and Reproductive Imagery in East Asian Religions Edited by AnnaAndreevaandDominicSteavu LEIDEN |BOSTON For use by the Author only | © 2016 Koninklijke Brill NV ContentsContents v Contents Acknowledgements ix List of Figures and Tables xi Conventions and Abbreviations xiv List of Contributors xviii Introduction: Backdrops and Parallels to Embryological Discourse and Reproductive Imagery in East Asian Religions 1 Anna Andreeva and Dominic Steavu Part 1 China 1 Prenatal Infancy Regained: Great Peace (Taiping) Views on Procreation and Life Cycles 53 Grégoire Espesset 2 Conceiving the Embryo of Immortality: “Seed-People” and Sexual Rites in Early Taoism 87 Christine Mollier 3 Cosmos, Body, and Gestation in Taoist Meditation 111 Dominic Steavu 4 Symbolic Pregnancy and the Sexual Identity of Taoist Adepts 147 Catherine Despeux 5 Creation and Its Inversion: Cosmos, Human Being, and Elixir in the Cantong Qi (The Seal of the Unity of the Three) 186 Fabrizio Pregadio 6 On the Effectiveness of Symbols: Women’s Bodies as Mandalas 212 Brigitte Baptandier For use by the Author only | © 2016 Koninklijke Brill NV vi Contents Part 2 Japan 7 The Embryonic Generation of the Perfect Body: Ritual Embryology from Japanese Tantric Sources 253 Lucia Dolce 8 Buddhism Ab Ovo: Aspects of Embryological Discourse in Medieval Japanese Buddhism 311 Bernard Faure 9 “Human Yellow” and Magical Power in Japanese Medieval Tantrism and Culture 344 Nobumi Iyanaga 10 “Lost in the Womb”: Conception, Reproductive Imagery, -

The Revival of Tiantai Buddhism in the Late Ming: on the Thought of Youxi Chuandeng 幽溪傳燈 (1554-1628)

The Revival of Tiantai Buddhism in the Late Ming: On the Thought of Youxi Chuandeng 幽溪傳燈 (1554-1628) Yungfen Ma Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2011 © 2011 Yungfen Ma All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The Revival of Tiantai Buddhism in the Late Ming: On the Thought of Youxi Chuandeng 幽溪傳燈 (1554-1628) Yungfen Ma This dissertation is a study of Youxi Chuandeng’s (1554-1628) transformation of “Buddha-nature includes good and evil,” also known as “inherent evil,” a unique idea representing Tiantai’s nature-inclusion philosophy in Chinese Buddhism. Focused on his major treatise On Nature Including Good and Evil, this research demonstrates how Chuandeng, in his efforts to regenerate Tiantai, incorporated the important intellectual themes of the late Ming, especially those found in the Śūraṃgama Sūtra. In his treatise, Chuandeng systematically presented his ideas on doctrinal classification, the principle of nature-inclusion, and the practice of the Dharma-gate of inherent evil. Redefining Tiantai doctrinal classification, he legitimized the idea of inherent evil to be the highest Buddhist teaching and proved the superiority of Buddhism over Confucianism. Drawing upon the notions of pure mind and the seven elements found in the Śūraṃgama Sūtra, he reinterpreted nature-inclusion and the Dharma-gate of inherent evil emphasizing inherent evil as pure rather than defiled. Conversely, he reinterpreted the Śūraṃgama Sūtra by nature-inclusion. Chuandeng incorporated Confucianism and the Śūraṃgama Sūtra as a response to the dominating thought of his day, this being the particular manner in which previous Tiantai thinkers upheld, defended and spread Tiantai. -

Fabrizio Pregadio CV

FABRIZIO PREGADIO Research Fellow (Wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiter) Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, Germany [email protected] RESEARCH SUBJECTS Daoism: thought, religion, and traditions of self-cultivation. — Chinese alchemy: Neidan (Internal Alchemy) and Waidan (External Alchemy).— Chinese views of human nature (xing 性) and destiny/ existence (ming 命). Main current research project: “Human Nature and Destiny in the Thought of the Daoist Master Liu Yiming (1734-1821)”, supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), 2020-2023. EDUCATION Degrees • Ph.D. (Civilizations of East Asia), Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, 1990 • M.A. (Chinese Language and Literature), Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, 1983 Other graduate study • University of Kyoto, Institute for Research in Humanities, 1985-90 • Italian School of East Asian Studies, Kyoto, 1985 Other undergraduate study • University of Leiden, Sinologisch Instituut (Linguistics of Classical Chinese), 1980-81 PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS Teaching • Erlangen University, Institute of Sinology: Guest Professor of Daoist Anthropology, from 2014-15 to 2017-18 • McGill University, Montreal, Department of East Asian Studies: Course Lecturer, 2009-2010 Fabrizio Pregadio — CV [Updated May 17, 2021] 1 • Stanford University, Department of Religious Studies: Visiting Professor, 2001-2002; Acting Associate Professor, 2002-2008 • Technische Universität Berlin, Institute of Philosophy: Visiting Professor, 1998 and 1999-2001 • Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, Department of East -

Buddhism and Taoism in the White Snake by Jerry James

Buddhism and Taoism in The White Snake by Jerry James “In the end, only three things matter: how much you loved, how gently you lived, and how gracefully you let go of things not meant for you.” This is a Buddhist saying, even though the sometime between the 4th and 6th centuries Buddha never said it. But it does resonate BCE. He was a scion of the royal family of the with Mary Zimmerman’s version of the Tale of warrior caste and was raised as a prince. the White Snake. Echoing the religious Edward Conze relates: practices of China itself, Zimmerman draws on various traditions to tell the story in her own At the age of 29, Siddhartha left his palace way. to meet his subjects. Despite his father's efforts to hide from him the sick, aged and In a similar manner, even though many of us suffering, Siddhartha was said to have had never heard of the White Snake before seen an old man. When his charioteer The Rogue announced its production, the explained to him that all people grew old, milieu in which the story originated and the prince went on further trips beyond continues to live has resonated with Western the palace. On these he encountered a culture for over 500 years, sometimes in diseased man, a decaying corpse, and an surprising ways, as we shall see. ascetic. These depressed him, and he initially strove to overcome aging, This tale was first fixed in tangible form in sickness, and death by living the life of an 1624, when Feng Menglong collected it in his ascetic. -

Curriculum Vitae Xunqiang

Curriculum Vitae Xunqiang Yin 1. Basic Information Full Name: Xunqiang Yin Nationality: Chinese Job Title: Physical Oceanographer Research Area ocean dynamics and modeling Education level: PhD The First Institute of Oceanography, Affiliation: Ministry of Natural Resources, China Address: No.6 Xian-Xia-Ling Road, Qingdao 266061 China Email: [email protected] 2. Work and Education Experience Education Sep.2008~Jul. 2015: Ph.D. Physical Oceanography, The Ocean University of China, China Sep.2002~Jul. 2005: M.S. Physical Oceanography, The First Institute of Oceanography, State Oceanic Administration, China Sep.1997~Jul. 2001: B.S. Physical Oceanography, The Ocean University of China, China Work Experience Dec. 2011~present: The First Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources, China, Associate Researcher Sep. 2006~Dec. 2011: The First Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources, China, Research Assistant Jun. 2005~Sep. 2006: Princeton University, USA, Visiting scholar/ Research Assistant Jul. 2001~Jun. 2005: The First Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources, China, Research Fellow. 3. Selected Publications 1) ZHAO Yiding, YIN Xunqiang, SONG Yajuan, QIAO Fangli. 2019. Seasonal prediction skills of FIO-ESM for North Pacific sea surface temperature and precipitation. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 38(1):5-12 2) Zhao Yiding,Yin Xunqiang, Song Yajuan, etal. Effect of wave-induced mixing on sea surface temperature seasonal prediction in the North Pacific in 2016 [J]. Haiyang Xuebao, 2019,41(3):52-61, doi: 10.3969/j.issn.0253-4193.2019.03.006(in Chinese) 3) Xunqiang Yin, Junqiang Shi, Fangli Qiao. Evaluation on surface current observing network of high frequency ground wave radars in the Gulf of Thailand, Ocean Dynamics, 2018, 68:575–587. -

Modern Daoism 149 New Texts and Gods 150 Ritual Masters 152 Complete Perfection 154 Imperial Adaptations 157 an Expanded Pantheon 161

Contents Illustrations v Map of China vii Dynastic Chart viii Pronunciation Guide x Background to Daoism 1 Shang Ancestors and Divination 2 The Yijing 4 Ancient Philosophical Schools 8 Confucianism 10 Part I: Foundations 15 The Daoism That Can’t Be Told 16 The Text of the Daode Jing 17 The Dao 20 Creation and Decline 22 The Sage 23 Interpreting the Daode Jing 25 Lord Lao 28 Ritual Application 30 At Ease in Perfect Happiness 35 The Zhuangzi 36 The World of ZHuang ZHou 38 The Ideal Life 41 Poetic Adaptations 43 The Zen Connection 46 From Health to Immortality 50 i Body Energetics 51 Qi Cultivation 52 Healing Exercises 54 Magical Practitioners and Immortals 59 Major Schools of the Middle Ages 64 Celestial Masters 65 Highest Clarity 66 Numinous Treasure 68 The Theocracy 70 The Three Caverns 71 State Religion 74 Cosmos, Gods, and Governance 80 Yin and Yang 81 The Five Phases 82 The Chinese Calendar 85 Deities, Demons, and Divine Rulers 87 The Ideal of Great Peace 92 Cosmic Cycles 94 Part II: Development 96 Ethics and the Community 97 The Celestial Connection 98 Millenarian Structures 100 Self-Cultivation Groups 103 Lay Organizations 105 The Monastic Life 108 Creation and the Pantheon 114 Creation 115 Spells, Charts, and Talismans 118 Heavens and Hells 122 ii Gods, Ancestors, and Immortals 125 Religious Practices 130 Longevity Techniques 131 Breath and Sex 134 Forms of Meditation 136 Body Transformation 140 Ritual Activation 143 Part III: Modernity 148 Modern Daoism 149 New Texts and Gods 150 Ritual Masters 152 Complete Perfection 154 Imperial -

Nourishing Life, Cultivation and Material Culture in the Late Ming: Some Th Oughts on Zunsheng Bajian 遵生八牋 (Eight Discourses on Respecting Life, 1591)*

Asian Medicine 4 (2008) 29–45 www.brill.nl/asme Nourishing Life, Cultivation and Material Culture in the Late Ming: Some Th oughts on Zunsheng bajian 遵生八牋 (Eight Discourses on Respecting Life, 1591)* Chen Hsiu-fen 陳秀芬 Abstract Th is article sets out to explore the ideas and practices of yangsheng 養生 (nourishing life or health preservation) in the late Ming, i.e. late sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century China. Yang sheng had long played a key role in the traditions of Chinese medicine, religions and court societies. Initially restricted to certain social classes and milieux, knowledge of yangsheng began to spread much more widely from the Song dynasty (960–1279) onwards, mostly owing to rapid social and economic change. In this context, the theories and practices of yangsheng attracted the atten- tion and curiosity of many scholars. Th e popularisation of yangsheng peaked in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Numerous literary works, essay collections and household encyclopaedias for everyday use have passages and sections on yangsheng. Th ey describe various ideas and tech- niques of yangsheng by means of regulating the body in daily life, involving sleeping, exercising, washing, eating, drinking, etc. Th rough a survey of the most famous late Ming work on yangsh- eng, Zunsheng bajian (1591), this article attempts to highlight how yangsheng came to dominate the scholarly lifestyle. It will give a clear picture of the ideas of a late Ming literatus on prolonging life and replenishing the body, while showing how these practices were inspired by the fl ourish- ing material culture of the late Ming as a whole.