Selections from Ancient Irish Poetry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manx Place-Names: an Ulster View

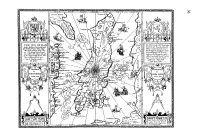

37 Manx Place-Names: an Ulster View Kay Muhr In this chapter I will discuss place-name connections between Ulster and Man, beginning with the early appearances of Man in Irish tradition and its association with the mythological realm of Emain Ablach, from the 6th to the I 3th century. 1 A good introduction to the link between Ulster and Manx place-names is to look at Speed's map of Man published in 1605.2 Although the map is much later than the beginning of place-names in the Isle of Man, it does reflect those place-names already well-established 400 years before our time. Moreover the gloriously exaggerated Manx-centric view, showing the island almost filling the Irish sea between Ireland, Scotland, England and Wales, also allows the map to illustrate place-names from the coasts of these lands around. As an island visible from these coasts Man has been influenced by all of them. In Ireland there are Gaelic, Norse and English names - the latter now the dominant language in new place-names, though it was not so in the past. The Gaelic names include the port towns of Knok (now Carrick-) fergus, "Fergus' hill" or "rock", the rock clearly referring to the site of the medieval castle. In 13th-century Scotland Fergus was understood as the king whose migration introduced the Gaelic language. Further south, Dundalk "fort of the small sword" includes the element dun "hill-fort", one of three fortification names common in early Irish place-names, the others being rath "ring fort" and lios "enclosure". -

The Poetry of Geoffrey Bache Smith with Special Note of Tolkienian Contexts

Journal of Tolkien Research Volume 12 Issue 2 Article 2 2021 The Poetry of Geoffrey Bache Smith with Special Note of Tolkienian Contexts Kris Swank University of Glasgow, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Swank, Kris (2021) "The Poetry of Geoffrey Bache Smith with Special Note of Tolkienian Contexts," Journal of Tolkien Research: Vol. 12 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch/vol12/iss2/2 This Conference Paper is brought to you for free and open access by ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Tolkien Research by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. The Poetry of Geoffrey Bache Smith with Special Note of Tolkienian Contexts Cover Page Footnote N.B. This paper grew from two directions: my PhD thesis work at the University of Glasgow under the direction of Dr. Dimitra Fimi, and conversations with John Garth beginning in Oxford during the summer of 2019. I’m grateful to both of them for their generosity and insights. This conference paper is available in Journal of Tolkien Research: https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch/ vol12/iss2/2 Swank: The Poetry of Geoffrey Bache Smith The Poetry of Geoffrey Bache Smith with Special Note of Tolkienian Contexts Kris Swank University of Glasgow presented at The Tolkien Symposium (May 8, 2021) sponsored by Tolkien@Kalamazoo, Dr. Christopher Vaccaro and Dr. Yvette Kisor, organizers The Voyage of Bran The Old Irish Voyage of Bran concerns an Otherworld voyage where, in one scene, Bran meets Manannán mac Ler, an Irish mythological figure who is often interpreted as a sea god. -

LANGUAGE Dictionaries 378 Dinneen, Patrick Stephen. an Irish-English

LANGUAGE Dictionaries 378 Dinneen, Patrick Stephen. An Irish-English dictionary, being thesaurus of the words, phrases and idioms of the modern Irish language. New ed., rev. and greatly enl. Dublin: 1927. 1340 p. List of Irish texts society's publications, etc.: 6 p. at end. A 2d edition which expanded the meanings and applications of key words, somatic terms and other important expressions. Contains words, phrases and idioms, of the modern Irish language. This, like other books published before 1948, is in the old spelling. 379 McKenna, Lambert Andrew Joseph. English-Irish dictionary. n.p.: 1935. xxii, 1546 p. List of sources: p. xv-xxii. Does not aim at giving all Irish equivalents for all English words, but at providing help for those wishing to write modern Irish. Places under the English head-word not only the Irish words which are equivalent, but also other Irish phrases which may be used to express the concept conveyed by the headword. Presupposes a fair knowledge of Irish, since phrases are used for illustration. Irish words are in Irish characters. ` Grammars 380 Dillon, Myles. Teach yourself Irish, by Myles Dillon and Donncha O Croinin. London: 1962. 243 p. Based on the dialect of West Munster, with purely dialect forms marked in most cases. Devotes much attention to important subject of idiomatic usages, but also has a thorough account of grammar. The book suffers from overcrowding, due to its compact nature, and from two other defects: insufficient sub-headings, and scant attention to pronunciation. 381 Gill, William Walter. Manx dialect, words and phrases. London: 1934. -

Ogma's Tale: the Dagda and the Morrigan at the River Unius

Ogma’s Tale: The Dagda and the Morrigan at the River Unius Presented to Whispering Lake Grove for Samhain, October 30, 2016 by Nathan Large A tale you’ve asked, and a tale you shall have, of the Dagda and his envoy to the Morrigan. I’ve been tasked with the telling: lore-keeper of the Tuatha de Danann, champion to two kings, brother to the Good God, and as tied up in the tale as any… Ogma am I, this Samhain night. It was on a day just before Samhain that my brother and the dark queen met, he on his duties to our king, Nuada, and Lugh his battle master (and our half-brother besides). But before I come to that, let me set the stage. The Fomorians were a torment upon Eireann and a misery to we Tuatha, despite our past victory over the Fir Bolg. Though we gained three-quarters of Eireann at that first battle of Maige Tuireadh, we did not cast off the Fomor who oppressed the land. Worse, we also lost our king, Nuada, when the loss of his hand disqualified him from ruling. Instead, we accepted the rule of the half-Fomorian king, Bres, through whom the Fomorians exerted their control. Bres ruined the court of the Tuatha, stilling its songs, emptying its tables, and banning all competitions of skill. None of the court could perform their duties. I alone was permitted to serve, and that only to haul firewood for the hearth at Tara. Our first rejection of the Fomor was to unseat Bres, once Nuada was whole again, his hand restored. -

The Voyage of Bran Son of Febal

The Voyage of Bran Son of Febal to the Land of the Living AN OLD IRISH SAGA NOW FIRST EDITED, WITH TRANSLATION, NOTES, AND GLOSSARY, BY Kuno Meyer London: Published by David Nutt in the Strand [1895] The Voyage of Bran Son of Febal to the Land of the Living Page 1 INTRODUCTION THE old-Irish tale which is here edited and fully translated 1 for the first time, has come down to us in seven MSS. of different age and varying value. It is unfortunate that the oldest copy (U), that contained on p. 121a of the Leabhar na hUidhre, a MS. written about 1100 A.D., is a mere fragment, containing but the very end of the story from lil in chertle dia dernaind (§ 62 of my edition) to the conclusion. The other six MSS. all belong to a much later age, the fourteenth, fifteenth, and sixteenth centuries respectively. Here follow a list and description of these MSS.:-- By R I denote a copy contained in the well-known Bodleian vellum quarto, marked Rawlinson B. 512, fo. 119a, 1-120b, 2. For a detailed description of this codex, see the Rolls edition of the Tripartite Life, vol. i. pp. xiv.-xlv. As the folios containing the copy of our text belong to that portion of the MS. which begins with the Baile in Scáil (fo. 101a), it is very probable that, like this tale, they were copied from the lost book of Dubdálethe, bishop of p. viii [paragraph continues] Armagh from 1049 to 1064. See Rev. Celt. xi. -

CELTIC MYTHOLOGY Ii

i CELTIC MYTHOLOGY ii OTHER TITLES BY PHILIP FREEMAN The World of Saint Patrick iii ✦ CELTIC MYTHOLOGY Tales of Gods, Goddesses, and Heroes PHILIP FREEMAN 1 iv 1 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America. © Philip Freeman 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer. CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress ISBN 978–0–19–046047–1 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America v CONTENTS Introduction: Who Were the Celts? ix Pronunciation Guide xvii 1. The Earliest Celtic Gods 1 2. The Book of Invasions 14 3. The Wooing of Étaín 29 4. Cú Chulainn and the Táin Bó Cuailnge 46 The Discovery of the Táin 47 The Conception of Conchobar 48 The Curse of Macha 50 The Exile of the Sons of Uisliu 52 The Birth of Cú Chulainn 57 The Boyhood Deeds of Cú Chulainn 61 The Wooing of Emer 71 The Death of Aife’s Only Son 75 The Táin Begins 77 Single Combat 82 Cú Chulainn and Ferdia 86 The Final Battle 89 vi vi | Contents 5. -

Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race by Thomas William Rolleston

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race by Thomas William Rolleston This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race Author: Thomas William Rolleston Release Date: October 16, 2010 [Ebook 34081] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MYTHS AND LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE*** MYTHS & LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE Queen Maev T. W. ROLLESTON MYTHS & LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE CONSTABLE - LONDON [8] British edition published by Constable and Company Limited, London First published 1911 by George G. Harrap & Co., London [9] PREFACE The Past may be forgotten, but it never dies. The elements which in the most remote times have entered into a nation's composition endure through all its history, and help to mould that history, and to stamp the character and genius of the people. The examination, therefore, of these elements, and the recognition, as far as possible, of the part they have actually contributed to the warp and weft of a nation's life, must be a matter of no small interest and importance to those who realise that the present is the child of the past, and the future of the present; who will not regard themselves, their kinsfolk, and their fellow-citizens as mere transitory phantoms, hurrying from darkness into darkness, but who know that, in them, a vast historic stream of national life is passing from its distant and mysterious origin towards a future which is largely conditioned by all the past wanderings of that human stream, but which is also, in no small degree, what they, by their courage, their patriotism, their knowledge, and their understanding, choose to make it. -

Ancient Greek Tragedy and Irish Epic in Modern Irish

MEMORABLE BARBARITIES AND NATIONAL MYTHS: ANCIENT GREEK TRAGEDY AND IRISH EPIC IN MODERN IRISH THEATRE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Katherine Anne Hennessey, B.A., M.A. ____________________________ Dr. Susan Cannon Harris, Director Graduate Program in English Notre Dame, Indiana March 2008 MEMORABLE BARBARITIES AND NATIONAL MYTHS: ANCIENT GREEK TRAGEDY AND IRISH EPIC IN MODERN IRISH THEATRE Abstract by Katherine Anne Hennessey Over the course of the 20th century, Irish playwrights penned scores of adaptations of Greek tragedy and Irish epic, and this theatrical phenomenon continues to flourish in the 21st century. My dissertation examines the performance history of such adaptations at Dublin’s two flagship theatres: the Abbey, founded in 1904 by W.B. Yeats and Lady Gregory, and the Gate, established in 1928 by Micheál Mac Liammóir and Hilton Edwards. I argue that the potent rivalry between these two theatres is most acutely manifest in their production of these plays, and that in fact these adaptations of ancient literature constitute a “disputed territory” upon which each theatre stakes a claim of artistic and aesthetic preeminence. Partially because of its long-standing claim to the title of Ireland’s “National Theatre,” the Abbey has been the subject of the preponderance of scholarly criticism about the history of Irish theatre, while the Gate has received comparatively scarce academic attention. I contend, however, that the history of the Abbey--and of modern Irish theatre as a whole--cannot be properly understood except in relation to the strikingly different aesthetics practiced at the Gate. -

Sacred-Outcast-Lyrics

WHITE HORSES White horses white horses ride the wave Manannan Mac Lir makes love in the cave The seed of his sea foam caresses the sand enters her womb and makes love to the land Manannan Mac Lir God of the Sea deep calm and gentle rough wild and free deep calm and gentle rough wild and free Her bones call him to her twice a day the moon drives him forward then takes him away His team of white horses shake their manes unbridled and passionate he rides forth again Manannan Mac Lir God of the Sea deep calm and gentle rough wild and free deep calm and gentle rough wild and free he’s faithful he’s constant its time to rejoice the salt in his kisses gives strength to her voice the fertile Earth Mother yearns on his foam to enter her deeply make love to the Crone Manannan Mac Lir God of the Sea deep calm and gentle rough wild and free deep calm and gentle deep calm and gentle deep calm and gentle deep calm and gentle deep calm and gentle Rough wild and free BONE MOTHER Bone Bone Bone Bone Mother Bone Bone Bone Crone Crone Crone Crone Beira Crone Crone Crone, Cailleach She stirs her cauldron underground Cerridwen. TRIPLE GODDESS Bridghid, Bride, Bree, Triple Goddess come to me Triple Goddess come to me Her fiery touch upon the frozen earth Releases the waters time for rebirth Bridghid Bride Bree Triple Goddess come to me Triple Goddess come to me Her mantle awakens snowdrops first Her fire and her waters sprout life in the earth Bridghid Bride Bree Triple Goddess come to me Triple Goddess come to me Imbolc is her season the coming of Spring Gifts of song and smithcraft and healing she brings Bridghid Bride Bree Triple Goddess come to me Triple Goddess come to me Triple Goddess come to me SUN GOD LUGH In days of old the stories told of the Sun God Lugh Born…… of the Aes Dana, half Fomorian too Sun God Sun God Sun God Lugh From Kian’s seed and Ethlin’s womb Golden threads to light the moon A boy to grow in all the arts To dance with Bride within our hearts Hopeful vibrant a visionary sight Creative gifts shining bright. -

The Song of the Silver Branch: Healing the Human-Nature Relationship in the Irish Druidic Tradition

The Song of the Silver Branch: Healing the Human-Nature Relationship in the Irish Druidic Tradition Jason Kirkey Naropa University Interdisciplinary Studies November 29th, 2007 Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know. —John Keats1 To be human, when being human is a habit we have broken, that is a wonder. —John Moriarty2 At the Hill of Tara in the sacred center of Ireland a man could be seen walking across the fields toward the great hall, the seat of the high king. Not any man was this, but Lúgh. He came because the Fomorian people made war with the Tuatha Dé Danann, two tribes of people living in Ireland. A war between dark and light. A war between two people experiencing the world in two opposing ways. The Tuatha Dé, content to live with nature, ruled only though the sovereignty of the land. The Fomorians, not so content, were possessed with Súil Milldagach, the destructive eye which eradicated anything it looked upon, were intent on ravaging the land. Lúgh approached the doorkeeper at the great hall who was instructed not to let any man pass the gates who did not possess an art. Not only possessing of an art, but one which was not already possessed by someone within the hall. The doorkeeper told this to Lúgh who replied, “Question me doorkeeper, I am a warrior.” But there was a warrior at Tara already. “Question me doorkeeper, I am a smith,” but there was already a smith. “Question me doorkeeper,” said Lúgh again, “I am a poet,” and again the doorkeeper replied that there was a poet at Tara already. -

Julius Pokorny Source: the Celtic Review, Vol

Review Author(s): Julius Pokorny Review by: Julius Pokorny Source: The Celtic Review, Vol. 6, No. 21 (Jul., 1909), pp. 93-96 Published by: Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30070204 Accessed: 23-10-2015 15:59 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.255.6.125 on Fri, 23 Oct 2015 15:59:49 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions BOOK REVIEWS 93 All who have had experience of the unfair treatment sometimes meted to Celtic-speaking witnesses by monoglot English magistrates will be interested in the conduct of an important trial at Carpentras during May. The majority of the witnesses appealed to the President of the Court for permission to give evidence in Provengal, saying that it was the only language of which they had complete command. Parisian advocates engaged in the case objected on the ground that they did not understand Provengal; but the President replied that they could avail themselves of the services of an interpreter, and that, in the interests of exact truth, the request of the witnesses would be granted. -

Celtic Mythology Ebook

CELTIC MYTHOLOGY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John Arnott MacCulloch | 288 pages | 16 Nov 2004 | Dover Publications Inc. | 9780486436562 | English | New York, United States Celtic Mythology PDF Book It's amazing the similarities. In has even influenced a number of movies, video games, and modern stories such as the Lord of the Rings saga by J. Accept Read More. Please do not copy anything without permission. Vocational Training. Thus the Celtic goddess, often portrayed as a beautiful and mature woman, was associated with nature and the spiritual essence of nature, while also representing the contrasting yet cyclic aspects of prosperity, wisdom, death, and regeneration. Yours divine voice Whispers the poetry of magic that flow through the wind, Like sweet-tasting water of the Boyne. Some of the essential female deities are Morrigan , Badb , and Nemain the three war goddess who appeared as ravens during battles. The Gods told us to do it. Thus over time, Belenus was also associated with the healing and regenerative aspects of Apollo , with healing shrines dedicated to the dual entities found across western Europe, including the one at Sainte-Sabine in Burgundy and even others as far away as Inveresk in Scotland. In most ancient mythical narratives, we rarely come across divine entities that are solely associated with language. Most of the records were taken around the 11 th century. In any case, Aengus turned out to be a lively man with a charming if somewhat whimsical character who always had four birds hovering and chirping around his head. They were a pagan people, who did not believe in written language.