James Clerk Maxwell, William Thomson, Fleeming Jenkin, and the Invention of the Dimensional Formula

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

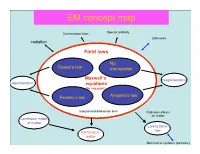

EM Concept Map

EM concept map Conservation laws Special relativity EM waves radiation Field laws No Gauss’s law monopoles ConservationMaxwell’s laws magnetostatics electrostatics equations (In vacuum) Faraday’s law Ampere’s law Integral and differential form Radiation effects on matter Continuum model of matter Lorenz force law EM fields in matter Mechanical systems (particles) Electricity and Magnetism PHYS-350: (updated Sept. 9th, (1605-1725 Monday, Wednesday, Leacock 109) 2010) Instructor: Shaun Lovejoy, Rutherford Physics, rm. 213, local Outline: 6537, email: [email protected]. 1. Vector Analysis: Tutorials: Tuesdays 4:15pm-5:15pm, location: the “Boardroom” Algebra, differential and integral calculus, curvilinear coordinates, (the southwest corner, ground floor of Rutherford physics). Office Hours: Thursday 4-5pm (either Lhermitte or Gervais, see Dirac function, potentials. the schedule on the course site). 2. Electrostatics: Teaching assistant: Julien Lhermitte, rm. 422, local 7033, email: Definitions, basic notions, laws, divergence and curl of the electric [email protected] potential, work and energy. Gervais, Hua Long, ERP-230, [email protected] 3. Special techniques: Math background: Prerequisites: Math 222A,B (Calculus III= Laplace's equation, images, seperation of variables, multipole multivariate calculus), 223A,B (Linear algebra), expansion. Corequisites: 314A (Advanced Calculus = vector 4. Electrostatic fields in matter: calculus), 315A (Ordinary differential equations) Polarization, electric displacement, dielectrics. Primary Course Book: "Introduction to Electrodynamics" by D. 5. Magnetostatics: J. Griffiths, Prentice-Hall, (1999, third edition). Lorenz force law, Biot-Savart law, divergence and curl of B, vector Similar books: potentials. -“Electromagnetism”, G. L. Pollack, D. R. Stump, Addison and 6. Magnetostatic fields in matter: Wesley, 2002. -

Gauss' Linking Number Revisited

October 18, 2011 9:17 WSPC/S0218-2165 134-JKTR S0218216511009261 Journal of Knot Theory and Its Ramifications Vol. 20, No. 10 (2011) 1325–1343 c World Scientific Publishing Company DOI: 10.1142/S0218216511009261 GAUSS’ LINKING NUMBER REVISITED RENZO L. RICCA∗ Department of Mathematics and Applications, University of Milano-Bicocca, Via Cozzi 53, 20125 Milano, Italy [email protected] BERNARDO NIPOTI Department of Mathematics “F. Casorati”, University of Pavia, Via Ferrata 1, 27100 Pavia, Italy Accepted 6 August 2010 ABSTRACT In this paper we provide a mathematical reconstruction of what might have been Gauss’ own derivation of the linking number of 1833, providing also an alternative, explicit proof of its modern interpretation in terms of degree, signed crossings and inter- section number. The reconstruction presented here is entirely based on an accurate study of Gauss’ own work on terrestrial magnetism. A brief discussion of a possibly indepen- dent derivation made by Maxwell in 1867 completes this reconstruction. Since the linking number interpretations in terms of degree, signed crossings and intersection index play such an important role in modern mathematical physics, we offer a direct proof of their equivalence. Explicit examples of its interpretation in terms of oriented area are also provided. Keywords: Linking number; potential; degree; signed crossings; intersection number; oriented area. Mathematics Subject Classification 2010: 57M25, 57M27, 78A25 1. Introduction The concept of linking number was introduced by Gauss in a brief note on his diary in 1833 (see Sec. 2 below), but no proof was given, neither of its derivation, nor of its topological meaning. Its derivation remained indeed a mystery. -

Dimensional Analysis and the Theory of Natural Units

LIBRARY TECHNICAL REPORT SECTION SCHOOL NAVAL POSTGRADUATE MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA 93940 NPS-57Gn71101A NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL Monterey, California DIMENSIONAL ANALYSIS AND THE THEORY OF NATURAL UNITS "by T. H. Gawain, D.Sc. October 1971 lllp FEDDOCS public This document has been approved for D 208.14/2:NPS-57GN71101A unlimited release and sale; i^ distribution is NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL Monterey, California Rear Admiral A. S. Goodfellow, Jr., USN M. U. Clauser Superintendent Provost ABSTRACT: This monograph has been prepared as a text on dimensional analysis for students of Aeronautics at this School. It develops the subject from a viewpoint which is inadequately treated in most standard texts hut which the author's experience has shown to be valuable to students and professionals alike. The analysis treats two types of consistent units, namely, fixed units and natural units. Fixed units include those encountered in the various familiar English and metric systems. Natural units are not fixed in magnitude once and for all but depend on certain physical reference parameters which change with the problem under consideration. Detailed rules are given for the orderly choice of such dimensional reference parameters and for their use in various applications. It is shown that when transformed into natural units, all physical quantities are reduced to dimensionless form. The dimension- less parameters of the well known Pi Theorem are shown to be in this category. An important corollary is proved, namely that any valid physical equation remains valid if all dimensional quantities in the equation be replaced by their dimensionless counterparts in any consistent system of natural units. -

Summary of Changes for Bidder Reference. It Does Not Go Into the Project Manual. It Is Simply a Reference of the Changes Made in the Frontal Documents

Community Colleges of Spokane ALSC Architects, P.S. SCC Lair Remodel 203 North Washington, Suite 400 2019-167 G(2-1) Spokane, WA 99201 ALSC Job No. 2019-010 January 10, 2020 Page 1 ADDENDUM NO. 1 The additions, omissions, clarifications and corrections contained herein shall be made to drawings and specifications for the project and shall be included in scope of work and proposals to be submitted. References made below to specifications and drawings shall be used as a general guide only. Bidder shall determine the work affected by Addendum items. General and Bidding Requirements: 1. Pre-Bid Meeting Pre-Bid Meeting notes and sign in sheet attached 2. Summary of Changes Summary of Changes for bidder reference. It does not go into the Project Manual. It is simply a reference of the changes made in the frontal documents. It is not a part of the construction documents. In the Specifications: 1. Section 00 30 00 REPLACED section in its entirety. See Summary of Instruction to Bidders Changes for description of changes 2. Section 00 60 00 REPLACED section in its entirety. See Summary of General and Supplementary Conditions Changes for description of changes 3. Section 00 73 10 DELETE section in its entirety. Liquidated Damages Checklist Mead School District ALSC Architects, P.S. New Elementary School 203 North Washington, Suite 400 ALSC Job No. 2018-022 Spokane, WA 99201 March 26, 2019 Page 2 ADDENDUM NO. 1 4. Section 23 09 00 Section 2.3.F CHANGED paragraph to read “All Instrumentation and Control Systems controllers shall have a communication port for connections with the operator interfaces using the LonWorks Data Link/Physical layer protocol.” A. -

Natural Units Conversions and Fundamental Constants James D

February 2, 2016 Natural Units Conversions and Fundamental Constants James D. Wells Michigan Center for Theoretical Physics (MCTP) University of Michigan, Ann Arbor Abstract: Conversions are listed between basis units of natural units system where ~ = c = 1. Important fundamental constants are given in various equivalent natural units based on GeV, seconds, and meters. Natural units basic conversions Natural units are defined to give ~ = c = 1. All quantities with units then can be written in terms of a single base unit. It is customary in high-energy physics to use the base unit GeV. But it can be helpful to think about the equivalences in terms of other base units, such as seconds, meters and even femtobarns. The conversion factors are based on various combinations of ~ and c (Olive 2014). For example −25 1 = ~ = 6:58211928(15) × 10 GeV s; and (1) 1 = c = 2:99792458 × 108 m s−1: (2) From this we can derive several useful basic conversion factors and 1 = ~c = 0:197327 GeV fm; and (3) 2 11 2 1 = (~c) = 3:89379 × 10 GeV fb (4) where I have not included the error in ~c conversion but if needed can be obtained by consulting the error in ~. Note, the value of c has no error since it serves to define the meter, which is the distance light travels in vacuum in 1=299792458 of a second (Olive 2014). The unit fb is a femtobarn, which is 10−15 barns. A barn is defined to be 1 barn = 10−24 cm2. The prefexes letters, such as p on pb, etc., mean to multiply the unit after it by the appropropriate power: femto (f) 10−15, pico (p) 10−12, nano (n) 10−9, micro (µ) 10−6, milli (m) 10−3, kilo (k) 103, mega (M) 106, giga (G) 109, terra (T) 1012, and peta (P) 1015. -

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI)

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) m kg s cd SI mol K A NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Ambler Thompson and Barry N. Taylor NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Ambler Thompson Technology Services and Barry N. Taylor Physics Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, 1995 Edition, April 1995) March 2008 U.S. Department of Commerce Carlos M. Gutierrez, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology James M. Turner, Acting Director National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication 811, 2008 Edition (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, April 1995 Edition) Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Publ. 811, 2008 Ed., 85 pages (March 2008; 2nd printing November 2008) CODEN: NSPUE3 Note on 2nd printing: This 2nd printing dated November 2008 of NIST SP811 corrects a number of minor typographical errors present in the 1st printing dated March 2008. Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Preface The International System of Units, universally abbreviated SI (from the French Le Système International d’Unités), is the modern metric system of measurement. Long the dominant measurement system used in science, the SI is becoming the dominant measurement system used in international commerce. The Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of August 1988 [Public Law (PL) 100-418] changed the name of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and gave to NIST the added task of helping U.S. -

English Customary Weights and Measures

English Customary Weights and Measures Distance In all traditional measuring systems, short distance units are based on the dimensions of the human body. The inch represents the width of a thumb; in fact, in many languages, the word for "inch" is also the word for "thumb." The foot (12 inches) was originally the length of a human foot, although it has evolved to be longer than most people's feet. The yard (3 feet) seems to have gotten its start in England as the name of a 3-foot measuring stick, but it is also understood to be the distance from the tip of the nose to the end of the middle finger of the outstretched hand. Finally, if you stretch your arms out to the sides as far as possible, your total "arm span," from one fingertip to the other, is a fathom (6 feet). Historically, there are many other "natural units" of the same kind, including the digit (the width of a finger, 0.75 inch), the nail (length of the last two joints of the middle finger, 3 digits or 2.25 inches), the palm (width of the palm, 3 inches), the hand (4 inches), the shaftment (width of the hand and outstretched thumb, 2 palms or 6 inches), the span (width of the outstretched hand, from the tip of the thumb to the tip of the little finger, 3 palms or 9 inches), and the cubit (length of the forearm, 18 inches). In Anglo-Saxon England (before the Norman conquest of 1066), short distances seem to have been measured in several ways. -

Towards Effective Teaching of Units and Measurements in Nigerian Secondary Schools: Guidelines for Physics Teachers

TOWARDS EFFECTIVE TEACHING OF UNITS AND MEASUREMENTS IN NIGERIAN SECONDARY SCHOOLS: GUIDELINES FOR PHYSICS TEACHERS Isa Shehu Usman Department of Science and Technology Education, University of Jos and Meshack Audu Lauco Department of Science Laboratory Technology Federal Polytechnic Kaura Namoda Abstract The concern of Physics educators in today's modem world is that teaching of physics should shift from teacher-dominated approach to student-centered approach of hands-on and minds-on activities. The relevance of units and measurements particularly in sciences and commerce in today's world cannot be over-emphasised. Through units and measurements, one can determine the magnitude of certain physical quantities. It is good to realise that when measurements are carried out, it must be followed by their units otherwise the values obtained become meaningless. Based on these assertions, this paper examined the brief h/story of units and measurements, concepts of units and measurements, the international Standard Units (SI) units and the traditional systems of units and measurements. The paper as well provided some guidelines for physics teachers on units and measurements and ended up with student's activities and recommendations. Physics is a practical and experimental science. Its relevance to scientific and technological development of any nation cannot be overemphasized. As such, its effective teaching and learning must be encouraged by all nations of the world. During practical and experiments, teachers usually ask students to measure length, mass, temperature, time and so on of different objects using some measuring instruments. Students carry out these activities in the laboratory during practical and experiments. They do these activities using knowledge and skills imparted to them by their teachers. -

Maxwell's Equations, Part II

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Chemistry Faculty Publications Chemistry Department 6-2011 Maxwell's Equations, Part II David W. Ball Cleveland State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/scichem_facpub Part of the Physical Chemistry Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Ball, David W. 2011. "Maxwell's Equations, Part II." Spectroscopy 26, no. 6: 14-21 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Chemistry Department at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chemistry Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maxwell’s Equations ρ II. ∇⋅E = ε0 This is the second part of a multi-part production on Maxwell’s equations of electromagnetism. The ultimate goal is a definitive explanation of these four equations; readers will be left to judge how definitive it is. A note: for certain reasons, figures are being numbered sequentially throughout this series, which is why the first figure in this column is numbered 8. I hope this does not cause confusion. Another note: this is going to get a bit mathematical. It can’t be helped: models of the physical universe, like Newton’s second law F = ma, are based in math. So are Maxwell’s equations. Enter Stage Left: Maxwell James Clerk Maxwell (Figure 8) was born in 1831 in Edinburgh, Scotland. His unusual middle name derives from his uncle, who was the 6th Baronet Clerk of Penicuik (pronounced “penny-cook”), a town not far from Edinburgh. -

English Version

UNESCO World Heritage Convention World Heritage Committee 2011 Addendum Evaluations of Nominations of Cultural and Mixed Properties ICOMOS report for the World Heritage Committee, 35th ordinary session UNESCO, June 2011 Secrétariat ICOMOS International 49-51 rue de la Fédération 75015 Paris France Tel : 33 (0)1 45 67 67 70 Fax : 33 (0)1 45 66 06 22 World Heritage List Nominations received by 1st February 2011 V Mixed properties A Asia - Pacific Minor modifications to the boundaries Australia [N/C 147ter] Kakadu National Park 1 VI Cultural properties A Africa Properties referred back by previous sessions of the World Heritage Committee Ethiopia [C 1333rev] The Konso Cultural Landscape 2 Kenya [C 1295rev] Fort Jesus, Mombasa 16 Minor modifications to the boundaries Mauritius [C 1259] Le Morne Cultural Landscape 29 B Arab States Creation of buffer zone Syrian Arab Republic [C 20] Ancient City of Damascus 30 C Asia - Pacific Minor modifications to the boundaries Malaysia [C 1223] Melaka and George Town, Historic Cities of the Straits of Malacca 32 D Europe Properties referred back by previous sessions of the World Heritage Committee France [C 1153rev] The Causses and the Cévennes, Mediterranean agro-pastoral Cultural Landscape 34 France, Argentina, Belgium, Germany, Japan, Switzerland [C 1321rev] The architectural work of Le Corbusier, an outstanding contribution to the Modern Movement 47 Israel [C 1105rev] The Triple-arch Gate at Dan 72 Minor modifications to the boundaries Cyprus [C 848] Choirokoitia 83 Italy [C 726] Historic Centre of Naples 85 Spain [C 522rev] Renaissance Monumental Ensembles of Úbeda and Baeza 87 Creation of buffer zone Germany [C 271] Pilgrimage Church of Wies 89 Germany [C 515rev] Abbey and Altenmünster of Lorsch 90 E Latin America and the Caribbean Minor modifications to the boundaries Chile [C 1178] Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works 92 Creation of buffer zone Honduras [C 129] Maya Site of Copan 94 surrounded by the property, which currently extends to 1.98 million hectares. -

9 the Psychological Reality of Grammar: a Student's-Eye View of Cognitive Science

9 The psychological reality of grammar: a student's-eye view of cognitive science Thomas G. Bever Never mind about the why: figure out the how, and the why will take care of itself. Lord Peter Wimsey Introduction This is a cautionary historical tale about the scientific study of what we know, what we do, and how we acquire what we know and do. There are two opposed paradigms in psychological science that deal with these interrelated topics: The behaviorist prescribes possible adult structures in terms of a theory of what can be learned; the rationalist explores adult structures in order to find out what a developmental theory must explain. The essential moral of the recent history of cognitive science is that it is more productive to explore mental life than pre scribe it. The classical period Experimental cognitive psychology was born the first time at the end of the nineteenth century. The pervasive bureaucratic work in psychology by Wundt (1874) and the thoughtful organization by James (1890) demonstrated that ex periments on mental life both can be done and are interesting. Language was an obviously appropriate object of this kind of psychological study. Wundt (1911), in particular, gave great attention to summarizing a century of research on the natural units and structure oflanguage; (see especially, Humboldt, 1835; Chom sky, 1966). He reported a striking conclusion: The natural unit of linguistic knowledge is the intuition that a sequence is a sentence. He reasoned as follows: All of the cited articles coauthored by me were substantially written when I was an asso ciate in George A. -

The International System of Units (SI) - Conversion Factors For

NIST Special Publication 1038 The International System of Units (SI) – Conversion Factors for General Use Kenneth Butcher Linda Crown Elizabeth J. Gentry Weights and Measures Division Technology Services NIST Special Publication 1038 The International System of Units (SI) - Conversion Factors for General Use Editors: Kenneth S. Butcher Linda D. Crown Elizabeth J. Gentry Weights and Measures Division Carol Hockert, Chief Weights and Measures Division Technology Services National Institute of Standards and Technology May 2006 U.S. Department of Commerce Carlo M. Gutierrez, Secretary Technology Administration Robert Cresanti, Under Secretary of Commerce for Technology National Institute of Standards and Technology William Jeffrey, Director Certain commercial entities, equipment, or materials may be identified in this document in order to describe an experimental procedure or concept adequately. Such identification is not intended to imply recommendation or endorsement by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, nor is it intended to imply that the entities, materials, or equipment are necessarily the best available for the purpose. National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publications 1038 Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Pub. 1038, 24 pages (May 2006) Available through NIST Weights and Measures Division STOP 2600 Gaithersburg, MD 20899-2600 Phone: (301) 975-4004 — Fax: (301) 926-0647 Internet: www.nist.gov/owm or www.nist.gov/metric TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD.................................................................................................................................................................v