Dimensional Analysis and the Theory of Natural Units

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 5 Dimensional Analysis and Similarity

Chapter 5 Dimensional Analysis and Similarity Motivation. In this chapter we discuss the planning, presentation, and interpretation of experimental data. We shall try to convince you that such data are best presented in dimensionless form. Experiments which might result in tables of output, or even mul- tiple volumes of tables, might be reduced to a single set of curves—or even a single curve—when suitably nondimensionalized. The technique for doing this is dimensional analysis. Chapter 3 presented gross control-volume balances of mass, momentum, and en- ergy which led to estimates of global parameters: mass flow, force, torque, total heat transfer. Chapter 4 presented infinitesimal balances which led to the basic partial dif- ferential equations of fluid flow and some particular solutions. These two chapters cov- ered analytical techniques, which are limited to fairly simple geometries and well- defined boundary conditions. Probably one-third of fluid-flow problems can be attacked in this analytical or theoretical manner. The other two-thirds of all fluid problems are too complex, both geometrically and physically, to be solved analytically. They must be tested by experiment. Their behav- ior is reported as experimental data. Such data are much more useful if they are ex- pressed in compact, economic form. Graphs are especially useful, since tabulated data cannot be absorbed, nor can the trends and rates of change be observed, by most en- gineering eyes. These are the motivations for dimensional analysis. The technique is traditional in fluid mechanics and is useful in all engineering and physical sciences, with notable uses also seen in the biological and social sciences. -

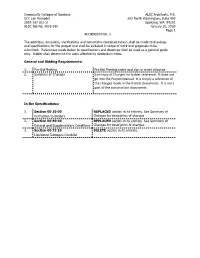

Summary of Changes for Bidder Reference. It Does Not Go Into the Project Manual. It Is Simply a Reference of the Changes Made in the Frontal Documents

Community Colleges of Spokane ALSC Architects, P.S. SCC Lair Remodel 203 North Washington, Suite 400 2019-167 G(2-1) Spokane, WA 99201 ALSC Job No. 2019-010 January 10, 2020 Page 1 ADDENDUM NO. 1 The additions, omissions, clarifications and corrections contained herein shall be made to drawings and specifications for the project and shall be included in scope of work and proposals to be submitted. References made below to specifications and drawings shall be used as a general guide only. Bidder shall determine the work affected by Addendum items. General and Bidding Requirements: 1. Pre-Bid Meeting Pre-Bid Meeting notes and sign in sheet attached 2. Summary of Changes Summary of Changes for bidder reference. It does not go into the Project Manual. It is simply a reference of the changes made in the frontal documents. It is not a part of the construction documents. In the Specifications: 1. Section 00 30 00 REPLACED section in its entirety. See Summary of Instruction to Bidders Changes for description of changes 2. Section 00 60 00 REPLACED section in its entirety. See Summary of General and Supplementary Conditions Changes for description of changes 3. Section 00 73 10 DELETE section in its entirety. Liquidated Damages Checklist Mead School District ALSC Architects, P.S. New Elementary School 203 North Washington, Suite 400 ALSC Job No. 2018-022 Spokane, WA 99201 March 26, 2019 Page 2 ADDENDUM NO. 1 4. Section 23 09 00 Section 2.3.F CHANGED paragraph to read “All Instrumentation and Control Systems controllers shall have a communication port for connections with the operator interfaces using the LonWorks Data Link/Physical layer protocol.” A. -

Three-Dimensional Analysis of the Hot-Spot Fuel Temperature in Pebble Bed and Prismatic Modular Reactors

Transactions of the Korean Nuclear Society Spring Meeting Chuncheon, Korea, May 25-26 2006 Three-Dimensional Analysis of the Hot-Spot Fuel Temperature in Pebble Bed and Prismatic Modular Reactors W. K. In,a S. W. Lee,a H. S. Lim,a W. J. Lee a a Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute, P. O. Box 105, Yuseong, Daejeon, Korea, 305-600, [email protected] 1. Introduction thousands of fuel particles. The pebble diameter is 60mm High temperature gas-cooled reactors(HTGR) have with a 5mm unfueled layer. Unstaggered and 2-D been reviewed as potential sources for future energy needs, staggered arrays of 3x3 pebbles as shown in Fig. 1 are particularly for a hydrogen production. Among the simulated to predict the temperature distribution in a hot- HTGRs, the pebble bed reactor(PBR) and a prismatic spot pebble core. Total number of nodes is 1,220,000 and modular reactor(PMR) are considered as the nuclear heat 1,060,000 for the unstaggered and staggered models, source in Korea’s nuclear hydrogen development and respectively. demonstration project. PBR uses coated fuel particles The GT-MHR(PMR) reactor core is loaded with an embedded in spherical graphite fuel pebbles. The fuel annular stack of hexahedral prismatic fuel assemblies, pebbles flow down through the core during an operation. which form 102 columns consisting of 10 fuel blocks PMR uses graphite fuel blocks which contain cylindrical stacked axially in each column. Each fuel block is a fuel compacts consisting of the fuel particles. The fuel triangular array of a fuel compact channel, a coolant blocks also contain coolant passages and locations for channel and a channel for a control rod. -

Natural Units Conversions and Fundamental Constants James D

February 2, 2016 Natural Units Conversions and Fundamental Constants James D. Wells Michigan Center for Theoretical Physics (MCTP) University of Michigan, Ann Arbor Abstract: Conversions are listed between basis units of natural units system where ~ = c = 1. Important fundamental constants are given in various equivalent natural units based on GeV, seconds, and meters. Natural units basic conversions Natural units are defined to give ~ = c = 1. All quantities with units then can be written in terms of a single base unit. It is customary in high-energy physics to use the base unit GeV. But it can be helpful to think about the equivalences in terms of other base units, such as seconds, meters and even femtobarns. The conversion factors are based on various combinations of ~ and c (Olive 2014). For example −25 1 = ~ = 6:58211928(15) × 10 GeV s; and (1) 1 = c = 2:99792458 × 108 m s−1: (2) From this we can derive several useful basic conversion factors and 1 = ~c = 0:197327 GeV fm; and (3) 2 11 2 1 = (~c) = 3:89379 × 10 GeV fb (4) where I have not included the error in ~c conversion but if needed can be obtained by consulting the error in ~. Note, the value of c has no error since it serves to define the meter, which is the distance light travels in vacuum in 1=299792458 of a second (Olive 2014). The unit fb is a femtobarn, which is 10−15 barns. A barn is defined to be 1 barn = 10−24 cm2. The prefexes letters, such as p on pb, etc., mean to multiply the unit after it by the appropropriate power: femto (f) 10−15, pico (p) 10−12, nano (n) 10−9, micro (µ) 10−6, milli (m) 10−3, kilo (k) 103, mega (M) 106, giga (G) 109, terra (T) 1012, and peta (P) 1015. -

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI)

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) m kg s cd SI mol K A NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Ambler Thompson and Barry N. Taylor NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Ambler Thompson Technology Services and Barry N. Taylor Physics Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, 1995 Edition, April 1995) March 2008 U.S. Department of Commerce Carlos M. Gutierrez, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology James M. Turner, Acting Director National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication 811, 2008 Edition (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, April 1995 Edition) Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Publ. 811, 2008 Ed., 85 pages (March 2008; 2nd printing November 2008) CODEN: NSPUE3 Note on 2nd printing: This 2nd printing dated November 2008 of NIST SP811 corrects a number of minor typographical errors present in the 1st printing dated March 2008. Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Preface The International System of Units, universally abbreviated SI (from the French Le Système International d’Unités), is the modern metric system of measurement. Long the dominant measurement system used in science, the SI is becoming the dominant measurement system used in international commerce. The Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of August 1988 [Public Law (PL) 100-418] changed the name of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and gave to NIST the added task of helping U.S. -

Introduction to Dimensional Analysis2 Usually, a Certain Physical Quantity

(2) Introduction to Dimensional Analysis2 Usually, a certain physical quantity, say, length or mass, is expressed by a number indicating how many times it is as large as a certain unit quantity. Therefore, the statement that the length of this stick is 3 does not make sense; we must say, with a certain unit, for example, that the length of this stick is 3 m. A number with a unit is a meaningless number as the number itself (3m and 9.8425¢ ¢ ¢ feet are the same). That is, we may freely scale it through choosing an appropriate unit. In contrast, the statement that the ratio of the lengths of this and that stick is 4 makes sense independent of the choice of the unit. A quantity whose numerical value does not depend on the choice of units is calle a dimensionless quantity. The number 4 here is dimensionless, and has an absolute meaning in contrast to the previous number 3. The statement that the length of this stick is 3m depends not only on the property of the stick but also on how we observe (or describe) it. In contrast, the statement that the ratio of the lengths is 4 is independent of the way we describe it. A formula describing a relation among several physical quantities is actually a relation among several numbers. If the physical relation holds `apart from us,' or in other words, is independent of the way we describe it, then whether the relation holds or not should not depend on the choice of the units or such `convenience to us.' A relation correct only when the length is measured in meters is hardly a good objective relation among physical quantities (it misses an important universal property of the law of physics, or at least very inconvenient). -

Summary of Dimensionless Numbers of Fluid Mechanics and Heat Transfer 1. Nusselt Number Average Nusselt Number: Nul = Convective

Jingwei Zhu http://jingweizhu.weebly.com/course-note.html Summary of Dimensionless Numbers of Fluid Mechanics and Heat Transfer 1. Nusselt number Average Nusselt number: convective heat transfer ℎ퐿 Nu = = L conductive heat transfer 푘 where L is the characteristic length, k is the thermal conductivity of the fluid, h is the convective heat transfer coefficient of the fluid. Selection of the characteristic length should be in the direction of growth (or thickness) of the boundary layer; some examples of characteristic length are: the outer diameter of a cylinder in (external) cross flow (perpendicular to the cylinder axis), the length of a vertical plate undergoing natural convection, or the diameter of a sphere. For complex shapes, the length may be defined as the volume of the fluid body divided by the surface area. The thermal conductivity of the fluid is typically (but not always) evaluated at the film temperature, which for engineering purposes may be calculated as the mean-average of the bulk fluid temperature T∞ and wall surface temperature Tw. Local Nusselt number: hxx Nu = x k The length x is defined to be the distance from the surface boundary to the local point of interest. 2. Prandtl number The Prandtl number Pr is a dimensionless number, named after the German physicist Ludwig Prandtl, defined as the ratio of momentum diffusivity (kinematic viscosity) to thermal diffusivity. That is, the Prandtl number is given as: viscous diffusion rate ν Cpμ Pr = = = thermal diffusion rate α k where: ν: kinematic viscosity, ν = μ/ρ, (SI units : m²/s) k α: thermal diffusivity, α = , (SI units : m²/s) ρCp μ: dynamic viscosity, (SI units : Pa ∗ s = N ∗ s/m²) W k: thermal conductivity, (SI units : ) m∗K J C : specific heat, (SI units : ) p kg∗K ρ: density, (SI units : kg/m³). -

Units of Measurement and Dimensional Analysis

Measurements and Dimensional Analysis POGIL ACTIVITY.2 Name ________________________________________ POGIL ACTIVITY 2 Units of Measurement and Dimensional Analysis A. Units of Measurement- The SI System and Metric System here are myriad units for measurement. For example, length is reported in miles T or kilometers; mass is measured in pounds or kilograms and volume can be given in gallons or liters. To avoid confusion, scientists have adopted an international system of units commonly known as the SI System. Standard units are called base units. Table A1. SI System (Systéme Internationale d’Unités) Measurement Base Unit Symbol mass gram g length meter m volume liter L temperature Kelvin K time second s energy joule j pressure atmosphere atm 7 Measurements and Dimensional Analysis POGIL. ACTIVITY.2 Name ________________________________________ The metric system combines the powers of ten and the base units from the SI System. Powers of ten are used to derive larger and smaller units, multiples of the base unit. Multiples of the base units are defined by a prefix. When metric units are attached to a number, the letter symbol is used to abbreviate the prefix and the unit. For example, 2.2 kilograms would be reported as 2.2 kg. Plural units, i.e., (kgs) are incorrect. Table A2. Common Metric Units Power Decimal Prefix Name of metric unit (and symbol) Of Ten equivalent (symbol) length volume mass 103 1000 kilo (k) kilometer (km) B kilogram (kg) Base 100 1 meter (m) Liter (L) gram (g) Unit 10-1 0.1 deci (d) A deciliter (dL) D 10-2 0.01 centi (c) centimeter (cm) C E 10-3 0.001 milli (m) millimeter (mm) milliliter (mL) milligram (mg) 10-6 0.000 001 micro () micrometer (m) microliter (L) microgram (g) Critical Thinking Questions CTQ 1 Consult Table A2. -

Planck Dimensional Analysis of Big G

Planck Dimensional Analysis of Big G Espen Gaarder Haug⇤ Norwegian University of Life Sciences July 3, 2016 Abstract This is a short note to show how big G can be derived from dimensional analysis by assuming that the Planck length [1] is much more fundamental than Newton’s gravitational constant. Key words: Big G, Newton, Planck units, Dimensional analysis, Fundamental constants, Atomism. 1 Dimensional Analysis Haug [2, 3, 4] has suggested that Newton’s gravitational constant (Big G) [5] can be written as l2c3 G = p ¯h Writing the gravitational constant in this way helps us to simplify and quantify a long series of equations in gravitational theory without changing the value of G, see [3]. This also enables us simplify the Planck units. We can find this G by solving for the Planck mass or the Planck length with respect to G, as has already been done by Haug. We will claim that G is not anything physical or tangible and that the Planck length may be much more fundamental than the Newton’s gravitational constant. If we assume the Planck length is a more fundamental constant than G,thenwecanalsofindG through “traditional” dimensional analysis. Here we will assume that the speed of light c, the Planck length lp, and the reduced Planck constanth ¯ are the three fundamental constants. The dimensions of G and the three fundamental constants are L3 [G]= MT2 L2 [¯h]=M T L [c]= T [lp]=L Based on this, we have ↵ β γ G = lp c ¯h L3 L β L2 γ = L↵ M (1) MT2 T T ✓ ◆ ✓ ◆ Based on this, we obtain the following three equations Lenght : 3 = ↵ + β +2γ (2) Mass : 1=γ (3) − Time : 2= β γ (4) − − − ⇤e-mail [email protected]. -

Department of Physics Notes on Dimensional Analysis and Units

1 CSUC Department of Physics 301A Mechanics: Notes on Dimensional Analysis and Units I. INTRODUCTION Physics has a particular interest in those attributes of nature which allow comparison processes. Such qualities include e.g. length, time, mass, force, energy...., etc. By \comparison process" we mean that although we recognize that, say, \length" is an abstract quality, nonetheless, any two \lengths" may successfully be compared in a generally agreed upon manner yielding a real number which we sometimes, by custom, call their \ratio". It's crucial to realize that this outcome it isn't really a mathematical ratio since the participants aren't numbers at all, but rather completely abstract entities . viz. \Physical Extent in Space". Thus we undertake to represent physical qualities (i.e. certain aspects) of our system with real numbers. In general, we recognize that only `lengths' can be compared to `other lengths' etc - i.e. that the world divides into exclusive classes (e.g. `all lengths') of entities which can be compared to each other. We say that all the entities in any one class are `mutually comparable' with each other. These physical numbers will be our basic tools for expressing the relationships we observe in nature. As we proceed in our understanding of the physical world we will come to understand that any (and ultimately every !) properly expressed relationship (e.g. our theories) has several universal aspects of structure which we will study using what we may call \dimensional analysis". These structural aspects are of enormous importance and will be, as you progress, among the very first things you examine in any physical problem you encounter. -

English Customary Weights and Measures

English Customary Weights and Measures Distance In all traditional measuring systems, short distance units are based on the dimensions of the human body. The inch represents the width of a thumb; in fact, in many languages, the word for "inch" is also the word for "thumb." The foot (12 inches) was originally the length of a human foot, although it has evolved to be longer than most people's feet. The yard (3 feet) seems to have gotten its start in England as the name of a 3-foot measuring stick, but it is also understood to be the distance from the tip of the nose to the end of the middle finger of the outstretched hand. Finally, if you stretch your arms out to the sides as far as possible, your total "arm span," from one fingertip to the other, is a fathom (6 feet). Historically, there are many other "natural units" of the same kind, including the digit (the width of a finger, 0.75 inch), the nail (length of the last two joints of the middle finger, 3 digits or 2.25 inches), the palm (width of the palm, 3 inches), the hand (4 inches), the shaftment (width of the hand and outstretched thumb, 2 palms or 6 inches), the span (width of the outstretched hand, from the tip of the thumb to the tip of the little finger, 3 palms or 9 inches), and the cubit (length of the forearm, 18 inches). In Anglo-Saxon England (before the Norman conquest of 1066), short distances seem to have been measured in several ways. -

Towards Effective Teaching of Units and Measurements in Nigerian Secondary Schools: Guidelines for Physics Teachers

TOWARDS EFFECTIVE TEACHING OF UNITS AND MEASUREMENTS IN NIGERIAN SECONDARY SCHOOLS: GUIDELINES FOR PHYSICS TEACHERS Isa Shehu Usman Department of Science and Technology Education, University of Jos and Meshack Audu Lauco Department of Science Laboratory Technology Federal Polytechnic Kaura Namoda Abstract The concern of Physics educators in today's modem world is that teaching of physics should shift from teacher-dominated approach to student-centered approach of hands-on and minds-on activities. The relevance of units and measurements particularly in sciences and commerce in today's world cannot be over-emphasised. Through units and measurements, one can determine the magnitude of certain physical quantities. It is good to realise that when measurements are carried out, it must be followed by their units otherwise the values obtained become meaningless. Based on these assertions, this paper examined the brief h/story of units and measurements, concepts of units and measurements, the international Standard Units (SI) units and the traditional systems of units and measurements. The paper as well provided some guidelines for physics teachers on units and measurements and ended up with student's activities and recommendations. Physics is a practical and experimental science. Its relevance to scientific and technological development of any nation cannot be overemphasized. As such, its effective teaching and learning must be encouraged by all nations of the world. During practical and experiments, teachers usually ask students to measure length, mass, temperature, time and so on of different objects using some measuring instruments. Students carry out these activities in the laboratory during practical and experiments. They do these activities using knowledge and skills imparted to them by their teachers.