Rivers, Roads, and Rails: the Influence of Rt Ansportation Needs and Internal Improvements on Cherokee Treaties and Removal from 1779 to 1838

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Register/Vol. 76, No. 4/Thursday, January 6, 2011/Notices

Federal Register / Vol. 76, No. 4 / Thursday, January 6, 2011 / Notices 795 responsibilities under NAGPRA, 25 reasonably traced between the DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S.C. 3003(d)(3). The determinations in unassociated funerary objects and the this notice are the sole responsibility of Alabama-Coushatta Tribes of Texas; National Park Service the Superintendent, Natchez Trace Alabama-Quassarte Tribal Town, [2253–65] Parkway, Tupelo, MS. Oklahoma; Chitimacha Tribe of In 1951, unassociated funerary objects Louisiana; Choctaw Nation of Notice of Inventory Completion for were removed from the Mangum site, Oklahoma; Jena Band of Choctaw Native American Human Remains and Claiborne County, MS, during Indians, Louisiana; Mississippi Band of Associated Funerary Objects in the authorized National Park Service survey Choctaw Indians, Mississippi; and Possession of the U.S. Department of and excavation projects. The Tunica-Biloxi Indian Tribe of Louisiana. the Interior, National Park Service, whereabouts of the human remains is Natchez Trace Parkway, Tupelo, MS; unknown. The 34 unassociated funerary Representatives of any other Indian Correction objects are 6 ceramic vessel fragments, tribe that believes itself to be culturally 1 ceramic jar, 4 projectile points, 6 shell affiliated with the unassociated funerary AGENCY: National Park Service, Interior. ornaments, 2 shells, 1 stone tool, 1 stone objects should contact Cameron H. ACTION: Notice; correction. artifact, 1 polished stone, 2 pieces of Sholly, Superintendent, Natchez Trace petrified wood, 2 bone artifacts, 1 Parkway, 2680 Natchez Trace Parkway, Notice is here given in accordance worked antler, 2 discoidals, 3 cupreous Tupelo, MS 38803, telephone (662) 680– with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act metal fragments and 2 soil/shell 4005, before February 7, 2011. -

Standards Addressed: 5.36 Identify the Year Tennessee Became a State, Its First Governor, and the Original Capital

Standards Addressed: 5.36 Identify the year Tennessee became a state, its first governor, and the original capital. (G, H, P, T) 5.35 Describe the steps that Tennessee took to become a state (i.e., population requirement, vote by the citizens, creation of a state constitution, and Congressional approval). (G, H, P, T, TCA) 5.34 Locate the Territory South of the River Ohio (i.e., Southwest Territory), identify its leaders, and explain how it was the first step to Tennessee’s statehood. (G, H, P, T) 8.28 Identify how westward expansion led to the statehood of Tennessee and the importance of the first state constitution (1796). (T.C.A. § 49-6-1028) G, H, P, T, TCA TN.10 Analyze the effects of land speculation on settlement in the Territory South of the River Ohio (i.e., the Southwest Territory). E, G, H, T TN.11 Analyze the conflicts between early Tennessee settlers and American Indians. E, G, H, T TN.12 Describe the events and trace the process of Tennessee achieving statehood in 1796. H, P, T Essential Question: What was William Blount’s role in Tennessee becoming a state? The teacher will begin the class by displaying a portrait of William Blount (the teacher should not disclose to students who the subject of the portrait is. The teacher will ask students what they physically see in the portrait. Then, the teacher will ask what they think about the portrait (e.g., do the students think the man is important, do they think he is trustworthy, etc.). -

Study Guide for the Georgia History Exemption Exam Below Are 99 Entries in the New Georgia Encyclopedia (Available At

Study guide for the Georgia History exemption exam Below are 99 entries in the New Georgia Encyclopedia (available at www.georgiaencyclopedia.org. Students who become familiar with these entries should be able to pass the Georgia history exam: 1. Georgia History: Overview 2. Mississippian Period: Overview 3. Hernando de Soto in Georgia 4. Spanish Missions 5. James Oglethorpe (1696-1785) 6. Yamacraw Indians 7. Malcontents 8. Tomochichi (ca. 1644-1739) 9. Royal Georgia, 1752-1776 10. Battle of Bloody Marsh 11. James Wright (1716-1785) 12. Salzburgers 13. Rice 14. Revolutionary War in Georgia 15. Button Gwinnett (1735-1777) 16. Lachlan McIntosh (1727-1806) 17. Mary Musgrove (ca. 1700-ca. 1763) 18. Yazoo Land Fraud 19. Major Ridge (ca. 1771-1839) 20. Eli Whitney in Georgia 21. Nancy Hart (ca. 1735-1830) 22. Slavery in Revolutionary Georgia 23. War of 1812 and Georgia 24. Cherokee Removal 25. Gold Rush 26. Cotton 27. William Harris Crawford (1772-1834) 28. John Ross (1790-1866) 29. Wilson Lumpkin (1783-1870) 30. Sequoyah (ca. 1770-ca. 1840) 31. Howell Cobb (1815-1868) 32. Robert Toombs (1810-1885) 33. Alexander Stephens (1812-1883) 34. Crawford Long (1815-1878) 35. William and Ellen Craft (1824-1900; 1826-1891) 36. Mark Anthony Cooper (1800-1885) 37. Roswell King (1765-1844) 38. Land Lottery System 39. Cherokee Removal 40. Worcester v. Georgia (1832) 41. Georgia in 1860 42. Georgia and the Sectional Crisis 43. Battle of Kennesaw Mountain 44. Sherman's March to the Sea 45. Deportation of Roswell Mill Women 46. Atlanta Campaign 47. Unionists 48. Joseph E. -

Washington County, Tennessee

1 WASHINGTON COUNTY, TENNESSEE: A BIBLIOGRAPHY The following is a bibliography of articles, books, theses, dissertations, reports, other printed items, and filmed documentaries related to various aspects of the history of Washington County, Tennessee and its’ people. Citations for which the archive has copies are marked with an asterisk. Alexander, J. E., with revisions by C. H. Mathes. A Historical Sketch of Washington College, Tennessee. (Washington College, Tenn.: Washington College Press, 1902). Alexander, Mary Henderson. “Black Life in Johnson City, Tennessee, 1856-1965: A Historical Chronology.” (Thesis, East Tennessee State University, 2001). * Alexander, Thomas B. Thomas A. R. Nelson of East Tennessee (Nashville: Tennessee Historical Commission, 1956). * Allison, John. Dropped Stitches in Tennessee History (Johnson City, Tenn.: Overmountain Press, 1991, reprint of 1897 edition). Ambler, Robert F. Embree Footprints: a Genealogy and Family History of the Embree Descendants of Robert of New Haven and Stamford, Connecticut, 1643-1656. (Robbinsdale, Minn.: R. F. Ambler, 1997). Archer, Cordelia Pearl. “History of the Schools of Johnson City, Tennessee, 1868- 1950” (Thesis, East Tennessee State College, 1953). Asbury, Francis. Journals and Letters. (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1958), vol. 1. Augsburg, Paul Deresco. Bob and Alf Taylor: Their Lives and Lectures; the story of Senator Robert Love Taylor and Governor Alfred Alexander Taylor. (Morristown, Tenn.: Morristown Book Company, Inc., c. 1925). Bailey, Chad F. “Heritage Tourism in Washington County, Tennessee: Linking Place, Placelessness, and Preservation.” (Thesis, East Tennessee State University, 2016). Bailey, William P. and Wendy Jayne. Green Meadows Mansion, Tipton Haynes State Historic Site: Historic Structure Report. (Nashville: Tennessee Historical Commission, 1991). * Bailey, William Perry, Jr. -

Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide

Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide Guide to the educational resources available on the GHS website Theme driven guide to: Online exhibits Biographical Materials Primary sources Classroom activities Today in Georgia History Episodes New Georgia Encyclopedia Articles Archival Collections Historical Markers Updated: July 2014 Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide Table of Contents Pre-Colonial Native American Cultures 1 Early European Exploration 2-3 Colonial Establishing the Colony 3-4 Trustee Georgia 5-6 Royal Georgia 7-8 Revolutionary Georgia and the American Revolution 8-10 Early Republic 10-12 Expansion and Conflict in Georgia Creek and Cherokee Removal 12-13 Technology, Agriculture, & Expansion of Slavery 14-15 Civil War, Reconstruction, and the New South Secession 15-16 Civil War 17-19 Reconstruction 19-21 New South 21-23 Rise of Modern Georgia Great Depression and the New Deal 23-24 Culture, Society, and Politics 25-26 Global Conflict World War One 26-27 World War Two 27-28 Modern Georgia Modern Civil Rights Movement 28-30 Post-World War Two Georgia 31-32 Georgia Since 1970 33-34 Pre-Colonial Chapter by Chapter Primary Sources Chapter 2 The First Peoples of Georgia Pages from the rare book Etowah Papers: Exploration of the Etowah site in Georgia. Includes images of the site and artifacts found at the site. Native American Cultures Opening America’s Archives Primary Sources Set 1 (Early Georgia) SS8H1— The development of Native American cultures and the impact of European exploration and settlement on the Native American cultures in Georgia. Illustration based on French descriptions of Florida Na- tive Americans. -

The Story of Natchez Trace Is the Story of the People

The story of Natchez Trace is the story of the saw villages in the northeastern part of the between Nashville and Natchez, but the few By 1819, 20 steamboats were operating Accommodations Natchez Trace Parkway people who used it: the Indians who traded and State. French traders, missionaries, and troops assigned the task could not hope to between New Orleans and such interior cities There are no overnight facilities along the park The parkway, which runs through Tennessee, hunted along it; the "Kaintuck" boatmen who soldiers frequently traveled over the old complete it without substantial assistance. So, as St. Louis, Louisville, and Nashville. No way. Motels, hotels, and restaurants may be found Alabama, and Mississippi, is administered by the pounded it into a rough wilderness road on Indian trade route. in 1808, Congress appropriated $6 thousand to longer was it necessary for the traveler to use in nearby towns and cities. The only service National Park Service, U.S. Department of the their way back from trading expeditions to In 1763 France ceded the region to allow the Postmaster General to contract for the trace in journeying north. Thus, steam station is at Jeff Busby. Campgrounds are at Interior. A superintendent, with offices in the Spanish Natchez and New Orleans; and the England, and under British rule a large popula improvements, and within a short time the old boats, new roads, new towns, and the passing Rocky Springs, Jeff Busby, and Meriwether Tupelo Visitor Center, is in charge. Send all in post riders, government officials, and soldiers tion of English-speaking people moved into Indian and boatmen trail became an important of the frontier finally reduced the trace to a Lewis. -

The Cherokee Removal and the Fourteenth Amendment

MAGLIOCCA.DOC 07/07/04 1:37 PM Duke Law Journal VOLUME 53 DECEMBER 2003 NUMBER 3 THE CHEROKEE REMOVAL AND THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT GERARD N. MAGLIOCCA† ABSTRACT This Article recasts the original understanding of the Fourteenth Amendment by showing how its drafters were influenced by the events that culminated in The Trail of Tears. A fresh review of the primary sources reveals that the removal of the Cherokee Tribe by President Andrew Jackson was a seminal moment that sparked the growth of the abolitionist movement and then shaped its thought for the next three decades on issues ranging from religious freedom to the antidiscrimination principle. When these same leaders wrote the Fourteenth Amendment, they expressly invoked the Cherokee Removal and the Supreme Court’s opinion in Worcester v. Georgia as relevant guideposts for interpreting the new constitutional text. The Article concludes by probing how that forgotten bond could provide the springboard for a reconsideration of free exercise and equal protection doctrine once courts begin exploring the meaning of this Cherokee Paradigm of the Fourteenth Amendment. Copyright © 2003 by Gerard N. Magliocca. † Assistant Professor, Indiana University School of Law—Indianapolis. J.D., Yale Law School, 1998; B.A., Stanford University, 1995. Many thanks to Bruce Ackerman, Bill Bradford, Daniel Cole, Kenny Crews, Brian C. Kalt, Robert Katz, Mary Mitchell, Allison Moore, Amanda L. Tyler, George Wright, and the members of the Northwestern University School of Law Constitutional Colloquium for their insights. Special thanks to Michael C. Dorf, Gary Lawson, Sandy Levinson, and Michael Klarman, who provided generous comments even though we had never met. -

Dot 16550 DS1.Pdf

DRAFT NOTES ON THE SEMINOLE TRAIL (U.S . 29) Ill VIRGIBU Howard Newloa, Jr. October 28, 1976 According to McCary the indians that inhabited Virginia prior to English settlement were linguistically Algonquian, 'Iroquoian and Siouan- The general areas are indicated on his map attached as Figure 1.") Harrison in his extensive work on Old Prince William which extended as far west as Fauquier County likewise describes the indians as Algonquian and Iroquois. Specific tribes associated with Piedmont Virginia are largeiy Sapoai, Hanahuac, Tutelo, and Occaneechi. No mention is made in any county or state histories consulted of habitation or travel in the Virginia area by Seminoles. Despite this, U.S. 29 between Warrenton and the Horth Carolina line in 1928 was designated "TIie Seminole Trail". This designation was apprwed as Senate Bill 64 on February 16, 1928, which stated 1. Be it enacted by the general assembly of Virginia that that part of the Virginia State highway system, beginning at the Borth Carolina line and leading through Danville , Chatham, Alta Vista, Lynchburg, Amherst, Lovingston, Charlottesville, Ruckersville, Nadison and Culpeper to Warrenton, be, and is hereby designated and shall. be, here- after , known as the "Seminole Trail.". No supporting arguments were found in the Senate Journal or other public documents in the University of Virginia Library. Like- wise no documentation or descriptions were found in tourist oriented publications. Thus a question remains as to the origin and validity of the designation. Attempts to find supporting evidence in published sources on American Indians were likewise unsuccessful. The mo8t extensive -1- documentation of Southeastern indian trails was published by Myer in 1928!3) His map is attached as Figure 2. -

United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma Hosts Keetoowah Cherokee Language Classes Throughout the Tribal Jurisdictional Area on an Ongoing Basis

OKLAHOMA INDIAN TRIBE EDUCATION GUIDE United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma (Oklahoma Social Studies Standards, OSDE) Tribe: United Keetoowah (ki-tu’-wa ) Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma Tribal website(s): www.keetoowahcherokee.org 1. Migration/movement/forced removal Oklahoma History C3 Standard 2.3 “Integrate visual and textual evidence to explain the reasons for and trace the migrations of Native American peoples including the Five Tribes into present-day Oklahoma, the Indian Removal Act of 1830, and tribal resistance to the forced relocations.” Oklahoma History C3 Standard 2.7 “Compare and contrast multiple points of view to evaluate the impact of the Dawes Act which resulted in the loss of tribal communal lands and the redistribution of lands by various means including land runs as typified by the Unassigned Lands and the Cherokee Outlet, lotteries, and tribal allotments.” Original Homeland Archeologists say that Keetoowah/Cherokee families began migrating to a new home in Arkansas by the late 1790's. A Cherokee delegation requested the President divide the upper towns, whose people wanted to establish a regular government, from the lower towns who wanted to continue living traditionally. On January 9, 1809, the President of the United States allowed the lower towns to send an exploring party to find suitable lands on the Arkansas and White Rivers. Seven of the most trusted men explored locations both in what is now Western Arkansas and also Northeastern Oklahoma. The people of the lower towns desired to remove across the Mississippi to this area, onto vacant lands within the United States so that they might continue the traditional Cherokee life. -

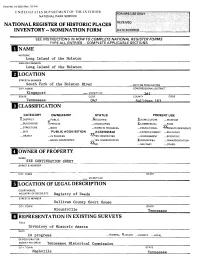

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STAThSDhPARTMHNT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ I NAME HISTORIC Long Island of the Holston AND/OR COMMON Long Island of the Holston LOCATION STREET& NUMBER South Fork of the Holston Elver _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Kingsport __. VICINITY OF 1st STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Tennessee 047 Sullivan 16^ HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE ^DISTRICT —PUBLIC -^OCCUPIED X.AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _ BUILDING(S) ^.PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED X-COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL ^r^RIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS •^TYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _ BEING CONSIDERED _ YES: UNRESTRICTED X-INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION X?NO _ MILITARY —OTHER: [OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME SEE CONTINUATION SHEET STREETS. NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE __ VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. Registry of Deeds STREET& NUMBER Sullivan County Court House CITY, TOWN STATE Blountville Tennessee I REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Inventory of Historic Assets DATE in progress — FEDERAL ?_STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Tennessee Historical Commission CITY, TOWN STATE Nashville Tennessee DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE -EXCELLENT X&ETERIORATED east _UNALTERED X.QRIGINALSITE west -RUINS XALTERED _MOVED DATE. _FA)R _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Long Island of the Holston is located along the South Fork of the Holston River just east of the junction of the North and South Forks and immediately south of the city of Kingsport, Tennessee. -

Horses, Culture, and Trade: the Impact of the Horse on Southeastern Native Nations, 1650-1830

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Master's Theses Summer 2019 Horses, Culture, and Trade: The Impact of the Horse on Southeastern Native Nations, 1650-1830 Jacob Featherling University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Featherling, Jacob, "Horses, Culture, and Trade: The Impact of the Horse on Southeastern Native Nations, 1650-1830" (2019). Master's Theses. 658. https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses/658 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HORSES, CULTURE, AND TRADE: THE IMPACT OF THE HORSE ON SOUTHEASTERN NATIVE NATIONS, 1650-1830 by Jacob Featherling A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Sciences and the School of Humanities at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by: Dr. Joshua Haynes, Committee Chair Dr. Kyle Zelner Dr. Max Grivno ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ Dr. Joshua Haynes Dr. Luis Iglesias Dr. Karen S. Coats Committee Chair Director of School Dean of the Graduate School August 2019 COPYRIGHT BY Jacob Featherling 2019 Published by the Graduate School ABSTRACT A small portion of the regional literature details the impact of horses on Southeastern Native nations and focuses on a few of the larger groups, particularly the Choctaw, from the mid-eighteenth to the nineteenth century. -

Paddler's Guide to Civil War Sites on the Water

Southeast Tennessee Paddler’s Guide to Civil War Sites on the Water If Rivers Could Speak... Chattanooga: Gateway to the Deep South nion and Confederate troops moved into Southeast Tennessee and North Georgia in the fall of 1863 after the Uinconclusive Battle of Stones River in Murfreesboro, Tenn. Both armies sought to capture Chattanooga, a city known as “The Gateway to the Deep South” due to its location along the he Tennessee River – one of North America’s great rivers – Tennessee River and its railroad access. President Abraham winds for miles through Southeast Tennessee, its volume Lincoln compared the importance of a Union victory in Tfortified by gushing creeks that tumble down the mountains Chattanooga to Richmond, Virginia - the capital of the into the Tennessee Valley. Throughout time, this river has Confederacy - because of its strategic location on the banks of witnessed humanity at its best and worst. the river. The name “Tennessee” comes from the Native American word There was a serious drought taking place in Southeast Tennessee “Tanasi,” and native people paddled the Tennessee River and in 1863, so water was a precious resource for soldiers. As troops its tributaries in dugout canoes for thousands of years. They strategized and moved through the region, the Tennessee River fished, bathed, drank and traveled these waters, which held and its tributaries served critical roles as both protective barriers dangers like whirlpools, rapids and eddies. Later, the river was and transportation routes for attacks. a thrilling danger for early settlers who launched out for a fresh The two most notorious battles that took place in the region start in flatboats.