1968, to December 31, 1968 You Are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State of New Jersey 2014-15 41-1870-050 OVERVIEW HACKETTSTOWN HIGH SCHOOL WARREN 701 WARREN STREET GRADE SPAN 09-12 HACKETTSTOWN HACKETTSTOWN, NJ 07840 1.00

State of New Jersey 2014-15 41-1870-050 OVERVIEW HACKETTSTOWN HIGH SCHOOL WARREN 701 WARREN STREET GRADE SPAN 09-12 HACKETTSTOWN HACKETTSTOWN, NJ 07840 1.00 The New Jersey Department of Education (NJDOE) is pleased to present these annual reports of School Performance. These reports are designed to inform parents, educators and communities about how well a school is performing and preparing its students for college and careers. In particular, the School Performance Reports seek to: Focus attention on metrics that are indicative of college and career readiness. Benchmark a school's performance against other peer schools that are educating similar students, against statewide outcomes, and against state targets to illuminate and build upon a school's strengths and identify areas for improvement. Improve educational outcomes for students by providing both longitudinal and growth data so that progress can be measured as part of an individual school's efforts to engage in continuous improvement. While the New Jersey School Performance Reports seek to bring more information to educators and stakeholders about the performance of schools, they do not seek to distill the performance of schools into a single metric, a single score, or a simplified conclusion. Instead, the intention is that educators and stakeholders will engage in deep, lengthy conversations about the full range of the data presented As educators know well, measuring school performance is both an art and a science. While the School Performance Report brings attention to important student outcomes, NJDOE does not collect data about other essential elements of a school, such as the provision of opportunities to participate and excel in extracurricular activities; the development of non-cognitive skills like time management and perseverance; the pervasiveness of a positive school culture or climate; or the attainment of other employability and technical skills, as many of these data are beyond both the capacity and resources of schools to measure and collect well. -

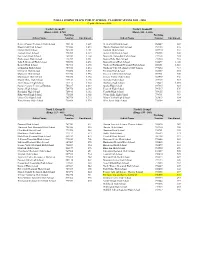

Njsiaa Wrestling Public School Classifications 2018 - 2019

NJSIAA WRESTLING PUBLIC SCHOOL CLASSIFICATIONS 2018 - 2019 North I, Group V North I, Group IV (Range 1,394 - 2,713) (Range 940 - 1,302) Northing Northing School Name Number Enrollment School Name Number Enrollment Bloomfield High School 712844 1,473 Belleville High School 716518 1,057 Clifton High School 742019 2,131 Cliffside Park High School 724048 940 East Orange Campus High School 701896 1,756 Fair Lawn High School 763923 1,102 Eastside High School 756591 2,304 Kearny High School 701968 1,293 Hackensack High School 745799 1,431 Morris Hills High School 745480 985 John F. Kennedy High School 756570 2,478 Morris Knolls High School 745479 1,100 Livingston High School 709106 1,434 Mount Olive High School 749123 1,158 Montclair High School 723754 1,596 Northern Highlands Regional HS 800331 1,021 Morristown High School 716336 1,394 Orange High School 701870 941 North Bergen High School 717175 1,852 Randolph High School 730913 1,182 Passaic County Technical Institute 763837 2,633 Ridgewood High School 778520 1,302 Passaic High School 734778 2,396 Roxbury High School 738224 1,010 Union City High School 705770 2,713 Wayne Hills High School 774731 953 West Orange High School 716434 1,574 Wayne Valley High School 763819 994 North I, Group III North I, Group II (Range 762 - 917) (Range 514 - 751) Northing Northing School Name Number Enrollment School Name Number Enrollment Bergenfield High School 760447 847 Dumont High School 767749 611 Dwight Morrow High School 753193 816 Glen Rock High School 771209 560 Indian Hills High School 796598 808 High -

Minutes 9/23/2019

BOONTON TOWN BOARD OF EDUCATION 434 Lathrop Avenue, Boonton, NJ 07005 September 23, 2019 I. CALL TO ORDER The Boonton Town Board of Education, of Morris County, New Jersey, held a meeting at 7:30 pm on September 23, 2019, at John Hill School, 435 Lathrop Avenue, Boonton, New Jersey. II. OPEN PUBLIC MEETING Mr. Joseph Geslao, Board President, called the meeting to order, and Mr. Steven Gardberg, Board Secretary, read the following statement: This is the September 23, 2019, meeting of the Boonton Town Board of Education. Pursuant to Section 5 of the Open Public Meetings Act, adequate notice of this meeting was provided to the Daily Record and the Citizen; distributed to The Neighbor News and the Boonton Town Clerk; and posted at the Board of Education Building at 434 Lathrop Avenue, Boonton, New Jersey. III. ROLL CALL Members present at roll call were Mr. Chris Cartelli, Mrs. Jennifer Darling, Mrs. Elaine Doherty, Mr. Bob Ezzi, Mr. Joe Geslao, Mrs. Loren Katsakos, Mrs. Irene LeFebvre, Mrs. Jennifer Shollenberger, Mr. Robert Stager. Absent: Mr. Patrick Joyce Also present were Mr. Robert Presuto, Superintendent and Mr. Steven Gardberg, School Business Administrator/Board Secretary and Felicia Kicinski, Assistant Business Administrator IV. EXECUTIVE SESSION On a motion at 7:33 pm by Mrs. Doherty and seconded by Mrs. LeFebvre, all present voted to enter Executive Session. Be it resolved, that the following portion of this meeting dealing with the following generally described matters shall not be open to the public: Personnel matters; Current or Potential Litigation; and Matters of Attorney/Client Privilege. -

Njsiaa Baseball Public School Classifications 2018 - 2020

NJSIAA BASEBALL PUBLIC SCHOOL CLASSIFICATIONS 2018 - 2020 North I, Group IV North I, Group III (Range 1,100 - 2,713) (Range 788 - 1,021) Northing Northing School Name Number Enrollment School Name Number Enrollment Bergen County Technical High School 753114 1,669 Bergenfield High School 760447 847 Bloomfield High School 712844 1,473 Dwight Morrow High School 753193 816 Clifton High School 742019 2,131 Garfield High School 745720 810 Eastside High School 756591 2,304 Indian Hills High School 796598 808 Fair Lawn High School 763923 1,102 Montville Township High School 749158 904 Hackensack High School 745799 1,431 Morris Hills High School 745480 985 John F. Kennedy High School 756570 2,478 Northern Highlands Regional High School 800331 1,021 Kearny High School 701968 1,293 Northern Valley Regional at Old Tappan 793284 917 Livingston High School 709106 1,434 Paramus High School 760357 894 Memorial High School 710478 1,502 Parsippany Hills High School 738197 788 Montclair High School 723754 1,596 Pascack Valley High School 789561 908 Morris Knolls High School 745479 1,100 Passaic Valley High School 741969 930 Morristown High School 716336 1,394 Ramapo High School 785705 885 Mount Olive High School 749123 1,158 River Dell Regional High School 767687 803 North Bergen High School 717175 1,852 Roxbury High School 738224 1,010 Passaic County Technical Institute 763837 2,633 Sparta High School 807435 824 Passaic High School 734778 2,396 Teaneck High School 749517 876 Randolph High School 730913 1,182 Tenafly High School 764155 910 Ridgewood High -

Town of Boonton School District Comprehensive

TOWN OF BOONTON SCHOOL DISTRICT COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED JUNE 30, 2015 Boonton, New Jersey COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT of the Town of Boonton School District Boonton, New Jersey For The Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2015 Prepared by Business Office TOWN OF BOONTON SCHOOL DISTRICT TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTORY SECTION Letter of Transmittal 1-lV Organizational Chart v Roster of Officials VI Consultants and Advisors Vll FINANCIAL SECTION Independent Auditor's Report 1-3 REQUIRED SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION-PART I Management's Discussion and Analysis 4-10 Basic Financial Statements A. District-wide Financial Statements A-1 Statement ofNet Position 11 A-2 Statement of Activities 12 B. Fund Financial Statements Governmental Funds B-1 Balance Sheet 13 B-2 Statement of Revenues, Expenditures, and Changes in Fund Balances 14 B-3 Reconciliation of the Governmental Funds Statement of Revenues, Expenditures and Changes in Fund Balances with the District-Wide Statements 15 Proprietary Funds B-4 Statement of Net Position 16 B-.5 Statement of Revenues, Expenses, and Changes in Fund Net Position 17 B-6 Statement of Cash Flows 18 Fiduciary Funds B-7 Statement of Fiduciary Net Position 19 B-8 Statement of Changes in Fiduciary Net Position 20 Notes to the Financial Statements 21-56 TOWN OF BOONTON SCHOOL DISTRICT TABLE OF CONTENTS REQUIRED SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION-PART IT C. Budgetary Comparison Schedules C-1 · Budgetary Comparison Schedule - General Fund 57-65 C-2 Budgetary Comparison Schedule- Special Revenue Fund 66 NOTES TO THE REQUIRED SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION-PART II C-3 Budgetary Comparison Schedule- Note to Required Supplementary Information 67 L. -

CEDAR GROVE BOARD of EDUCATION Cedar Grove, New Jersey AGENDA

CEDAR GROVE BOARD OF EDUCATION Cedar Grove, New Jersey AGENDA March 5, 2019 North End School Teachers Room Executive Session 6:30 PM North End Media Center Public Session 7:30 PM Call to order by the Board President Roll Call E1. Motion to adjourn to executive session to discuss the following items: Legal matter relative to Board litigation. Action is not expected to follow the discussion in Executive Session. Public release of the discussion will occur upon completion of the matter. Student matter relative to HIB. Action is not expected to follow the discussion in executive session. Due to the confidentiality of student matters, public release of this discussion will probably never occur. Contract matter relative to non-bargaining employees. Action is not expected to follow the discussion in Executive Session. Public release of the discussion will occur upon completion of any contracts. Student matter relative to suspensions. Action is not expected to follow the discussion in Executive Session. Public release of the discussion will probably never occur due to the confidentiality of the matter. Reconvene in Public Session Pledge of Allegiance Announcement: The New Jersey Open Public Meetings Law was enacted to ensure the right of the public to have advance notice of, and to attend the meeting of, public bodies at which any business affecting their interests is discussed or acted upon. In accordance with the provisions of this act, the Cedar Grove Board of Education has caused notice of this meeting to be advertised, by having the date, time, and place thereof posted on bulletin boards in the District, published and/or transmitted to the Verona-Cedar Grove Times and Star Ledger newspapers, TAPinto online news, filed with the Township Clerk, and posted on the District’s web site. -

Minutes 12/16/2019

BOONTON TOWN BOARD OF EDUCATION 434 Lathrop Avenue, Boonton, NJ 07005 December 16, 2019 I. CALL TO ORDER The Boonton Town Board of Education, of Morris County, New Jersey, held a meeting at 7:00 pm on December 16, 2019, at John Hill School, 435 Lathrop Avenue, Boonton, New Jersey. II. OPEN PUBLIC MEETING Mr. Joseph Geslao, Board President, called the meeting to order, and Mr. Steven Gardberg, Board Secretary, read the following statement: This is the December 16, 2019, meeting of the Boonton Town Board of Education. Pursuant to Section 5 of the Open Public Meetings Act, adequate notice of this meeting was provided to the Daily Record and the Citizen; distributed to The Neighbor News and the Boonton Town Clerk; and posted at the Board of Education Building at 434 Lathrop Avenue, Boonton, New Jersey. III. ROLL CALL Members present at roll call were Mr. Chris Cartelli, Mrs. Jennifer Darling, Mr. Bob Ezzi, Mr. Joe Geslao, Mr. Patrick Joyce, Mrs. Loren Katsakos, Mrs. Irene LeFebvre, Mrs. Jennifer Shollenberger, Mr. Robert Stager. Absent was Mrs. Elaine Doherty. Also present were Mr. Robert Presuto, Superintendent and Mr. Steven Gardberg, School Business Administrator/Board Secretary. IV. EXECUTIVE SESSION On a motion at 7:01 pm by Mr. Cartelli and seconded by Mrs. Darling, all present voted to enter Executive Session; Mrs. Doherty was absent. Be it resolved, that the following portion of this meeting dealing with the following generally described matters shall not be open to the public: Personnel matters; Current or Potential Litigation; and Matters of Attorney/Client Privilege. Be it further resolved, that it is anticipated that the matters to be considered in private may be disclosed to the public at a later date when confidentiality is no longer required. -

HS TSA Program 2018

Plan now to attend the Check us out on social media! 40th Annual Follow us on Twitter at National TSA Conference @NewJerseyTSA June 22-26, 2018 Atlanta, Georgia Follow us on Instagram at NJ_TSA Theme: “A Celebration of Success” Like us on Facebook at New Jersey Technology Student Association Use #NJTSA and post pictures to show us your experience at the 2018 NJ TSA State Conference! Get the chance to be retweeted by the Official NJ TSA Twitter or Instagram! TCNJ Campus Map STEM Building LOT 5 HIGH SCHOOL EVENTS ROOM TIME DESCRIPTION Schedule-at-a-Glance Participating Schools & Advisors 3D Animation AR 114 9:30am Display-open all day TIME EVENT LOCATION Atlantic County Institute of Technology………..…………………………………………………….……………….Patricia Czar Bayonne High School ………………………………………..………………………………………………………………… Marie Aloia Presentation 8:30am-9:30am Check-In & Breakfast Brower Student Center Biotechnology High School………………………………..………………..………………………………………… William Hercek Animatronics (Holding Room SS 225) SS 223 9:30am Display open after judging Boonton High School……………………………………………………………...……………………………………………Vicki Cornell 9:30am-3:30pm Competitive Events See opposite page for schedule Bordentown High School………………………………………….....………………...………………………………….Archna Ashish Architectural Design 9:30am and back cover for campus map AR 136 Display open after judging Brick Township High School……………………………………...…………………………………………………..Walter Hrycenko 9:30am 9:30am-3:30pm Spectator Events Open for Viewing Brick Township Memorial High School………………………...……………………………………………………...Daniel -

2017 High School Football

2017 HIGH SCHOOL FOOTBALL SEPTEMBER 7, 2017 NEW JERSEY HILLS MEDIA GROUP WWW.NEWJERSEYHILLS.COM PAGE 2 Thursday, September 7, 2017 FOOTBALL 2017 NEW JERSEY HILLS MEDIA GROUP Contact us at: www.morrishabitat.org/donate NEW JERSEY HILLS MEDIA GROUP FOOTBALL 2017 Thursday, September 7, 2017 PAGE 3 BERNARDS HIGH SCHOOL BERNARDS TO RELY ON SENIOR LEADERSHIP THIS SEASON By AMIT BATRA “It’s a tough one, but they have to come Bernards High School’s Jon SPORTS EDITOR here,” Simoneau said of the opener. “They are Simoneau will enter his 10th year as the complete opposite of us. They were in the head coach for the Mountaineers. BERNARDSVILLE – The Bernards High state championship last year, too. They lost, School football team will ask a lot of its seniors but they return 14 starters. We return three. Photo by Glenn Clark coming into the 2017 season. Once you play football, who knows.” The Mountaineers return four starters Some of the talent at the top will feature and five seniors overall. Head coach Jon senior offensive lineman/defensive lineman Simoneau, who is going into his 10th year, re- and team captain Cubby Schuller, who has re- alizes his team is young, but at the same time, ceived college offers from Yale University, Col- bodes talent across the roster. gate University, Columbia University and the “We’re really young,” Simoneau said. “Go- University of New Hampshire. He has been in ing on 10 years, this is the youngest we’ve ever the system these past few seasons and knows been with the amount of freshmen and sopho- his role is large on the team. -

Participaing Schools

Moody’s Mega Math Challenge 2017 ® A contest for high school students SIAM Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics 3600 Market Street, 6th Floor Philadelphia, PA 19104 USA [email protected] M3Challenge.siam.org M3 Challenge 2017 — Participating Teams by State Schools listed twice have two participating teams. School names appear exactly as they were entered on the registration form. ALABAMA ARCADIA SENIOR HIGH SCHOOL ORANGE CO HIGH SCH OF THE ARTS HELENA HIGH SCHOOL BAY SCHOOL AT SAN FRANCISCO PALOS VERDES HIGH SCHOOL HOOVER HIGH SCHOOL BAYFRONT CHARTER HIGH SCHOOL PIEDMONT HILLS HIGH SCHOOL LOVELESS ACADEMIC MAGNET HS BISHOP ALEMANY HIGH SCHOOL PINER HIGH SCHOOL MARY G MONTGOMERY HIGH SCHOOL CAPUCHINO HIGH SCHOOL PINER HIGH SCHOOL MARY G MONTGOMERY HIGH SCHOOL CARLMONT HIGH SCHOOL PLEASANT GROVE HIGH SCHOOL SMITHS STATION HIGH SCHOOL CARMEL HIGH SCHOOL PLEASANT GROVE HIGH SCHOOL STRAUGHN HIGH SCHOOL CAVA-INSIGHT AT SAN DIEGO RAMONA HIGH SCHOOL WEAVER HIGH SCHOOL CERRITOS HIGH SCHOOL RANCHO CAMPANA HIGH SCHOOL CHAMPS RIALTO HIGH SCHOOL ARIZONA COSUMNES OAKS HIGH SCHOOL RIALTO HIGH SCHOOL AAEC HIGH SCHOOL-ESTRELLA MTN DA VINCI SCHOOL-DESIGN RIO VISTA HIGH SCHOOL AAEC HIGH SCHOOL-ESTRELLA MTN DAVIS SENIOR HIGH SCHOOL RIVERA LC GREEN DESIGN SCHOOL AMERICAN LEADRSHP HS-QUEEN CRK DEL LAGO ACADEMY SANTA TERESA HIGH SCHOOL APOLLO HIGH SCHOOL DEL LAGO ACADEMY SANTA TERESA HIGH SCHOOL BASIS SCHOOL-CHANDLER DOZIER LIBBEY MEDICAL HIGH SCH SONOMA ACADEMY BUENA HIGH SCHOOL DOZIER LIBBEY MEDICAL HIGH SCH ST FRANCIS HIGH SCHOOL CHOLLA MAGNET -

CEDAR GROVE BOARD of EDUCATION Cedar Grove, New Jersey AGENDA

CEDAR GROVE BOARD OF EDUCATION Cedar Grove, New Jersey AGENDA August 20, 2019 Memorial Middle School Teachers’ Room Executive Session 6:30 PM Memorial Middle School Media Center Public Session 7:30 PM Call to order by the Board President Roll Call E1. Motion to adjourn to executive session to discuss the following items: Personnel matter relative to a Grievance. Action is not expected to follow the discussion in Executive Session. Public release of the discussion will occur upon completion of the matter. Personnel matter relative to Part Time, Non-Bargaining Employees. Action is not expected to follow the discussion in Executive Session. Public release of the discussion will occur upon completion of the matter. Reconvene in Public Session Pledge of Allegiance Announcement: The New Jersey Open Public Meetings Law was enacted to ensure the right of the public to have advance notice of, and to attend the meeting of, public bodies at which any business affecting their interests is discussed or acted upon. In accordance with the provisions of this act, the Cedar Grove Board of Education has caused notice of this meeting to be advertised, by having the date, time, and place thereof posted on bulletin boards in the District, published and/or transmitted to the Verona-Cedar Grove Times and Star Ledger newspapers, TAPinto online news, filed with the Township Clerk, and posted on the District’s web site. Roll Call THE MEETING IS OPEN TO THE PUBLIC FOR COMMENT ON ITEMS ON THE AGENDA. COMMITTEE REPORTS Curriculum Communications Facilities Finance Legislation Personnel Policy FSA/APT Board Presentation: Cedar Grove Board of Education Agenda August 20, 2019 Page 2 FROM THE OFFICE OF THE BUSINESS ADMINISTRATOR and BOARD SECRETARY MINUTES B1. -

NJSIAA SPRING TRACK PUBLIC SCHOOL CLASSIFICATIONS 2018 - 2020 (Updated February 2020)

NJSIAA SPRING TRACK PUBLIC SCHOOL CLASSIFICATIONS 2018 - 2020 (Updated February 2020) North I, Group IV North I, Group III (Range 1,102 - 2,713) (Range 808 - 1,100) Northing Northing School Name Number Enrollment School Name Number Enrollment Bergen County Technical High School 753114 1,669 Bergenfield High School 760447 847 Bloomfield High School 712844 1,473 Dwight Morrow High School 753193 816 Clifton High School 742019 2,131 Garfield High School 745720 810 Eastside High School 756591 2,304 Indian Hills High School 796598 808 Fair Lawn High School 763923 1,102 Montville Township High School 749158 904 Hackensack High School 745799 1,431 Morris Hills High School 745480 985 John F. Kennedy High School 756570 2,478 Morris Knolls High School 745479 1,100 Kearny High School 701968 1,293 Northern Highlands Regional High School 800331 1,021 Livingston High School 709106 1,434 Northern Valley Regional at Old Tappan 793284 917 Memorial High School 710478 1,502 Paramus High School 760357 894 Montclair High School 723754 1,596 Pascack Valley High School 789561 908 Morristown High School 716336 1,394 Passaic Valley High School 741969 930 Mount Olive High School 749123 1,158 Ramapo High School 785705 885 North Bergen High School 717175 1,852 Roxbury High School 738224 1,010 Passaic County Technical Institute 763837 2,633 Sparta High School 807435 824 Passaic High School 734778 2,396 Teaneck High School 749517 876 Randolph High School 730913 1,182 Tenafly High School 764155 910 Ridgewood High School 778520 1,302 Wayne Hills High School 774731 953