Vol31no2.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geologic Resources Inventory Scoping Summary Lewis and Clark National and State Historical Parks

Geologic Resources Inventory Scoping Summary Lewis and Clark National and State Historical Parks, Oregon and Washington Geologic Resources Division Prepared by John Graham National Park Service January 2010 US Department of the Interior The Geologic Resources Inventory (GRI) provides each of 270 identified natural area National Park System units with a geologic scoping meeting and summary (this document), a digital geologic map, and a Geologic Resources Inventory report. The purpose of scoping is to identify geologic mapping coverage and needs, distinctive geologic processes and features, resource management issues, and monitoring and research needs. Geologic scoping meetings generate an evaluation of the adequacy of existing geologic maps for resource management, provide an opportunity to discuss park-specific geologic management issues, and if possible include a site visit with local experts. The National Park Service held a GRI scoping meeting for Lewis and Clark National and State Historical Parks (LEWI) on October 14, 2009 at Fort Clatsop Visitors Center, Oregon. Meeting Facilitator Bruce Heise of the Geologic Resources Division (NPS GRD) introduced the Geologic Resources Inventory program and led the discussion regarding geologic processes, features, and issues at Lewis and Clark National and State Historical Parks. GIS Facilitator Greg Mack from the Pacific West Regional Office (NPS PWRO) facilitated the discussion of map coverage. Ian Madin, Chief Scientist with the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries (DOGAMI), presented an overview of the region’s geology. On Thursday, October 15, 2009, Tom Horning (Horning Geosciences) and Ian Madin (DOGAMI) led a field trip to several units within Lewis and Clark National and State Historical Parks. -

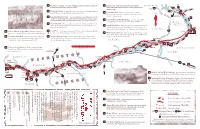

Discovery Trail Ilwaco, WA to Long Beach, WA

Volume 16, Issue 1 January 2015 Newsletter Worthy of Notice WASHINGTON STATE CHA PTER, LCTHF 2 0 1 5 Washington Chapter Annual Meeting D U E S : February 7, 2015 - Tacoma WA. S T I L L O N L Y speaker. During the morning session, Doc $ 1 5 . 0 0 ! will discuss the horses of the Lewis and Just a reminder to Clark expedition. send in your 2015 The election of Chapter officers and dues. If your mail- at-large board members will also be held. ing or email address The Chapter business meeting will follow has changed, please the lunch break. fill out the form on page 7 and mail it Silent Auction: all attendees are en- along with your couraged to bring items to donate for the check. Your mem- silent auction, with the proceeds going to bership helps support the Chapter. the activities of the Washington Chapter The Washington State Chapter of the throughout the year. Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Founda- tion will hold its Annual Meeting on Feb- ruary 7, 2015. The meeting will begin at 10:30 a.m. at the Washington State His- INSIDE THIS ISSUE: tory Museum in Tacoma, WA. All mem- bers are encouraged to attend if possible. President’s message 2 Doc Wesselius, former President and longtime member of the Washington LCTHF prize for National 3 State Chapter, will be our featured History Day Doc in the saddle Travelling the Washing- 4 ton Trail Submit your Nominations for Chapter Elections L&C Living History event 5 in Long Beach, WA At the annual meeting on February 7th, 2015, the Washington Chapter of the LCTHF will be electing officers and other mem- Positions open for The Adventures of Lewis 6 and Clark bers of the Board of Directors. -

January 2016 Newsletter

Volume 17, Issue 1 January 2016 Newsletter Worthy of Notice WASHINGTON STATE CHA PTER, LCTHF Washington Chapter Annual Meeting 2016 February 6, 2016 - Tacoma WA. D U E S : S T I L L The Washington State Chapter of the Elections: Members will vote for eight po- O N L Y sitions on the Chapter Board of Directors: $ 1 5 . 0 0 ! Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Founda- tion will hold its Annual Meeting on Feb- President Just a reminder to ruary 6, 2016. The meeting will begin at Vice President send in your 2016 10:30 a.m. at the Washington State His- Secretary dues. If your mail- tory Museum in Tacoma, WA. All mem- Treasurer ing or email address At-large Director (4 positions) has changed, please bers are encouraged to attend, and guests fill out the form on are also welcome. Nominations are being compiled by Tim page 7 and mail it There will be two featured speakers Underwood. The deadline for submitting along with your during the morning session, and both are nominees is Friday, January, 29th, 2016. check. Your mem- descendents of members of the Corps of Tim can be contacted through this e-mail bership helps support account: [email protected] or by regular the activities of the Discovery. Karen Willard will speak Washington Chapter about her connection to Alexander mail at… throughout the year. Willard, and Nik Taranik will share the family legacy of Patrick Gass. Tim Underwood The Chapter business meeting will 128 Galaxie Rd Chehalis, WA 98532 INSIDE THIS follow the lunch break and all are wel- ISSUE: come. -

One Hundred Eighth Congress of the United States of America

H. R. 3819 One Hundred Eighth Congress of the United States of America AT THE SECOND SESSION Begun and held at the City of Washington on Tuesday, the twentieth day of January, two thousand and four An Act To redesignate Fort Clatsop National Memorial as the Lewis and Clark National Historical Park, to include in the park sites in the State of Washington as well as the State of Oregon, and for other purposes. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, TITLE I—LEWIS AND CLARK NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK DESIGNATION ACT SEC. 101. SHORT TITLE. This title may be cited as the ‘‘Lewis and Clark National Historical Park Designation Act’’. SEC. 102. DEFINITIONS. As used in this title: (1) PARK.—The term ‘‘park’’ means the Lewis and Clark National Historical Park designated in section 103. (2) SECRETARY.—The term ‘‘Secretary’’ means the Secretary of the Interior. SEC. 103. LEWIS AND CLARK NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK. (a) DESIGNATION.—In order to preserve for the benefit of the people of the United States the historic, cultural, scenic, and natural resources associated with the arrival of the Lewis and Clark Expedi- tion in the lower Columbia River area, and for the purpose of commemorating the culmination and the winter encampment of the Lewis and Clark Expedition in the winter of 1805–1806 fol- lowing its successful crossing of the North American Continent, there is designated as a unit of the National Park System the Lewis and Clark National Historical Park. (b) BOUNDARIES.—The boundaries -

MICROCOMP Output File

108TH CONGRESS 2D SESSION S. 2167 AN ACT To establish the Lewis and Clark National Historical Park in the States of Washington and Oregon, and for other purposes. 1 Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representa- 2 tives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, 3 SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE. 4 This Act may be cited as the ‘‘Lewis and Clark Na- 5 tional Historical Park Act of 2004’’. 2 1 SEC. 2. PURPOSE. 2 The purpose of this Act is to establish the Lewis and 3 Clark National Historical Park to— 4 (1) preserve for the benefit of the people of the 5 United States the historic, cultural, scenic, and nat- 6 ural resources associated with the arrival of the 7 Lewis and Clark Expedition in the lower Columbia 8 River area; and 9 (2) commemorate the winter encampment of 10 the Lewis and Clark Expedition in the winter of 11 1805–1806 following the successful crossing of the 12 North American Continent. 13 SEC. 3. DEFINITIONS. 14 In this Act: 15 (1) MAP.—The term ‘‘map’’ means the map en- 16 titled ‘‘Lewis and Clark National Historical Park, 17 Boundary Map’’, numbered 405/80027, and dated 18 December, 2003. 19 (2) MEMORIAL.—The term ‘‘Memorial’’ means 20 the Fort Clatsop National Memorial established 21 under section 1 of Public Law 85–435 (16 U.S.C. 22 450mm). 23 (3) PARK.—The term ‘‘Park’’ means the Lewis 24 and Clark National Historical Park established by 25 section 4(a). †S 2167 ES 3 1 (4) SECRETARY.—The term ‘‘Secretary’’ means 2 the Secretary of the Interior. -

Lewis and Clark National Historical Park National Park Service

LEWIS AND CLARK NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK NATIONAL PARK SERVICE 61 ark Lewis and Clark National Historical P On December 10, 1805, members of the Corps the explorers. In addition to the fort, the Corps This fort exhibit, of Discovery began constructing a fort on the of Discovery also constructed a salt cairn near built in 1955, burned down in 2005. Park Netul River, now called the Lewis and Clark the present-day city of Seaside, Oregon, to staff and volunteers River, near present-day Astoria, Oregon. Fort extract salt from ocean water to help preserve immediately began Clatsop, named after the local Clatsop Indian and flavor meat for the return journey. work on a new tribe, was completed in a couple of weeks, and Upon leaving the fort on March 23, 1806, exhibit, which will be the party spent three and a half months there Lewis gave the structure and its furnishings to dedicated by the close of 2006. before commencing their return journey back Clatsop Chief Coboway. Over time, the fort east. The members of the expedition traded deteriorated and the land was claimed and sold with the Clatsop people, who were friendly to by various Euro-American settlers who came to Note: When interpreting the scores for natural resource conditions, recognize that critical information upon which the ratings are based is not always available. This limits data interpretation to some extent. For Lewis and Clark National Historical Park, 59 percent of the information requirements associated with the methods were met. RESOURCE CATEGORY CURRENT CULTURAL RESOURCES -

November 2008 Newsletter Vol

Worthy of Notice Washington State Chapter, LCTHF www.wa-lcthf.org November 2008 Newsletter Vol. 9, Issue 4 Tim Underwood, Editor [email protected] President’s Message: Heading into the holiday season, we need to take stock of the past year. Many things have happened in our lives, some more devastating than others, that left deeper scars than we care for. But we are resilient; we adapt and move on much as the Corps did on their epic traverse of North America. We also try to solve issues with common sense and knowledge gained from our experiences, again, much as the Corps did. There are many similarities in our lives today with those of the Corps in 1805. Though it was a military venture, the members had their own feelings and emotions when it came to national holidays. Perhaps Thanksgiving was less a holiday then, not referenced at all, but Christmas, New Years and Independence Day were definitely mentioned and observed. This is a time for us to embrace and enjoy our families and friends and to rekindle old friendships and enjoy our good fortunes as the Corps did when they finally reached the Pacific Ocean and had their winter quarters completed. During a recent chapter outing (see page 2), it became evident that both of the Pacific Northwest chapters were losing members. True, a drop in overall membership across the Foundation “Trail” was expected after the bicentennial – and it happened! We still need to maintain a steady level of membership in order to continue our efforts of maintenance, identification and education along The Trail. -

Douglas Deur Empires O the Turning Tide a History of Lewis and F Clark National Historical Park and the Columbia-Pacific Region

A History of Lewis and Clark National and State Historical Parks and the Columbia-Pacific Region Douglas Deur Empires o the Turning Tide A History of Lewis and f Clark National Historical Park and the Columbia-Pacific Region Douglas Deur 2016 With Contributions by Stephen R. Mark, Crater Lake National Park Deborah Confer, University of Washington Rachel Lahoff, Portland State University Members of the Wilkes Expedition, encountering the forests of the Astoria area in 1841. From Wilkes' Narrative (Wilkes 1845). Cover: "Lumbering," one of two murals depicting Oregon industries by artist Carl Morris; funded by the Work Projects Administration Federal Arts Project for the Eugene, Oregon Post Office, the mural was painted in 1942 and installed the following year. Back cover: Top: A ship rounds Cape Disappointment, in a watercolor by British spy Henry Warre in 1845. Image courtesy Oregon Historical Society. Middle: The view from Ecola State Park, looking south. Courtesy M.N. Pierce Photography. Bottom: A Joseph Hume Brand Salmon can label, showing a likeness of Joseph Hume, founder of the first Columbia-Pacific cannery in Knappton, Washington Territory. Image courtesy of Oregon State Archives, Historical Oregon Trademark #113. Cover and book design by Mary Williams Hyde. Fonts used in this book are old map fonts: Cabin, Merriweather and Cardo. Pacific West Region: Social Science Series Publication Number 2016-001 National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior ISBN 978-0-692-42174-1 Table of Contents Foreword: Land and Life in the Columbia-Pacific -

Lewis & Clark Map No K.Indd

Y a Y Y k 49 a i 43 a The Corps established a defensive position here on both the Named for the Corps' Private Jean Baptiste k m Rock Fort Campsite LePage Park W A N A P U M k 43 49 i 43 The Corps established a defensive position here on both the 49 Named for the Corps' Private Jean Baptiste im a Rock Fort Campsite The Corps established a defensive position here on both the LePage Park Named for the Corps' Private Jean Baptiste W A N A P U M m R. 395 a R outbound and return journeys. Interpretive signs. LePage, whose name Lewis & Clark gave to today's John Day River. R. 182 395 outbound and return journeys. Interpretive signs. LePage, whose name Lewis & Clark gave to today's John Day River. 82 182 v e r Interpretive sign. 82 182 k e R i v e r Interpretive sign. a k e R i v Interpretive sign. 12 n a k 240 PASCO S n 44 The Dalles Murals At several locations in the downtown area, large murals depict PASCO 12 S 44 The Dalles Murals At several locations in the downtown area, large murals depict 240 S Lewis & Clark's arrival and the Indian trading center at Celilo. 50 Crow Butte Park The Corps camped nearby, traveling by 60 Lewis & Clark's arrival and the Indian trading center at Celilo. 50 Crow Butte Park The Corps camped nearby, traveling by 60 horseback on the return jouney, long before dam flooding created 16-17 Oct. -

Congressional Record—Senate S12870

S12870 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE November 15, 2005 When Clark wrote that they had seen We would be wise to turn to Lewis odyssey of America, symbolic of the core the Pacific on that day, 200 years ago, and Clark again, as we confront so values of teamwork, courage, perseverance, he was slightly off target. They were many critical challenges before us science, and opportunity held by the United actually 25 miles away, in the Colum- today. States; Whereas, on October 30, 2004, President bia’s widening estuary. Only by truly reaching beyond our George W. Bush signed into law legislation Dangerous storms, wind, rain, and grasp, can we make our Nation great, creating the Lewis and Clark National His- waves battered them without relent. as Thomas Jefferson said: ‘‘from Sea to torical Park which preserves these 3 Wash- They were trapped for 6 days and Shining Sea.’’ ington State sites integral to the dramatic forced to hunker down at the spot we I yield the floor. arrival of the expedition at the Pacific now call Clark’s Dismal Nitch. Mr. SANTORUM. I ask unanimous Ocean, and incorporates Fort Clatsop of Or- When the weather finally cleared, consent that the resolution be agreed egon and important State parks for the ben- they moved west to Station Camp. to, the preamble be agreed to, the mo- efit and education of generations to come; and They set down for ten days and got tion to reconsider be laid upon the Whereas, during November 2005, Wash- their first real glimpse of the Pacific. table, and any statements relating ington and Oregon are hosting, ‘‘Destination: Expedition-member Sgt. -

Title I—Lewis and Clark National Historical Park

118 STAT. 2234 PUBLIC LAW 108–387—OCT. 30, 2004 Public Law 108–387 108th Congress An Act To redesignate Fort Clatsop National Memorial as the Lewis and Clark National Oct. 30, 2004 Historical Park, to include in the park sites in the State of Washington as [H.R. 3819] well as the State of Oregon, and for other purposes. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, Lewis and Clark TITLE I—LEWIS AND CLARK NATIONAL National Historical Park HISTORICAL PARK DESIGNATION ACT Designation Act. 16 USC 410kkk SEC. 101. SHORT TITLE. note. This title may be cited as the ‘‘Lewis and Clark National Historical Park Designation Act’’. 16 USC 410kkk. SEC. 102. DEFINITIONS. As used in this title: (1) PARK.—The term ‘‘park’’ means the Lewis and Clark National Historical Park designated in section 103. (2) SECRETARY.—The term ‘‘Secretary’’ means the Secretary of the Interior. 16 USC SEC. 103. LEWIS AND CLARK NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK. 410kkk–1. (a) DESIGNATION.—In order to preserve for the benefit of the people of the United States the historic, cultural, scenic, and natural resources associated with the arrival of the Lewis and Clark Expedi- tion in the lower Columbia River area, and for the purpose of commemorating the culmination and the winter encampment of the Lewis and Clark Expedition in the winter of 1805–1806 fol- lowing its successful crossing of the North American Continent, there is designated as a unit of the National Park System the Lewis and Clark National Historical Park. -

Columbia Estuary Ecosystem Restoration Program

BONNEVILLEPOWERADMINISTRATION In cooperation with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Columbia Estuary Ecosystem Restoration Program Final Environmental Assessment July 2016 DOE/EA-2006 BONNEVILLE POWER ADMINISTRATION DOE/BP-2006 • July 2016 Table of Contents Chapter 1 Purpose of and Need for Action ................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Need .................................................................................................................................................................. 3 1.3 Purposes.......................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.4 Background .................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.4.1 Federal Columbia River Power System ................................................................................... 4 1.4.2 Status of the Columbia River Estuary ...................................................................................... 4 1.4.3 Federal Columbia River Power System Biological Opinion ............................................ 5 1.4.4 Columbia Estuary Ecosystem Restoration Program .......................................................... 7 1.4.5