Copyright Is Owned by the Author of the Thesis. Permission Is Given for a Copy to Be Downloaded by an Individual for the Purpose of Research and Private Study Only

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(No. 1)Craccum-1974-048-001.Pdf

CRACCUM: FEBRUARY 25 1974 page 2 STAFF Editor.....................Brent Lewis Technical Editor................Malcolm Walker Chief Report ......... Mike Rann r o b b i e . Reporter................Bill Ralston Typist............. Wendy / am grateful to Brent Lewis, the Editor o f Craccum, for the opportunity o f Record Reviews............. Jeremy Templar expressing a few thoughts at the beginning o f a new University year, in Interview............... Ian Sinclair particular, I have been asked to express some opinions regarding present day youth. Advertising Manager ............. Graeme Easte Distribution ...... God Willing Legal V ettin g ............. Ken Palmer As far as I am aware, most University students take their studies seriously. At the same time, it is normal, natural and desirable, that they give expression Valuable Help Rendered B y ................ to youthful exuberance, provided this is within reasonable limits. Steve Ballantyne, Colin Chiles, Phyllis Connns, Roger Debreceny, Paul Halloran, John Langdon, Old Mole, Mike Moore, and Murray Cammick Also ran, Adrian Picot and Tony Dove. My experience with young people has demonstrated that in the main, they Items may be freely reprinted from Craccum except where otherwise stated, are responsible and recognise that society does not owe them a living, and provided that suitable acknowledgement is made. Craccum is published by the they must accept responsibilities in return for privileges. Criccum Administration Board for the Auckland University Students' Association (Inc), typeset by City Typesetters of 501 Parnell Road, Auckland, and printed by What we have to recognise is that .the technological, social and economic Wanganui Newspapers Ltd., 20 Drews Ave., Wanganui. changes that are always occurring, are now accelerating to the stage where it is difficult for the average person to keep up with them. -

Kiwisaver – Issues for Supplementary Drafting Instructions

PolicyP AdviceA DivisionD Treasury Report: KiwiSaver – Issues for Supplementary Drafting Instructions Date: 21 October 2005 Treasury Priority: High Security Level: IN-CONFIDENCE Report No: T2005/1974, PAD2005/186 Action Sought Action Sought Deadline Minister of Finance Agree to all recommendations 28 October 2005 Refer to Ministers of Education and Housing Minister of Commerce Agree to recommendations r to dd 28 October 2005 Minister of Revenue Agree to recommendations e to q 28 October 2005 Associate Minister of Finance Note None (Hon Phil Goff) Associate Minister of Finance Note None (Hon Trevor Mallard) Associate Minister of Finance Note None (Hon Clayton Cosgrove) Contact for Telephone Discussion (if required) Name Position Telephone 1st Contact Senior Analyst, Markets, Infrastructure 9 and Government, The Treasury Senior Policy Analyst, Regulatory and Competition Policy Branch, MED Michael Nutsford Policy Manager, Inland Revenue Enclosure: No Treasury:775533v1 IN-CONFIDENCE 21 October 2005 SH-13-0-7 Treasury Report: KiwiSaver – Issues for Supplementary Drafting Instructions Executive Summary Officials have provided the Parliamentary Counsel Office (PCO) with an initial set of drafting instructions on KiwiSaver. However, in preparing these drafting instructions, a range of further issues came to light. We are seeking decisions on these matters now so that officials can provide supplementary drafting instructions to PCO by early November. Officials understand that a meeting may be arranged between Ministers and officials for late next week to discuss the issues contained in this report and on the overall KiwiSaver timeline. A separate report discussing the timeline for KiwiSaver and the work on the taxation of qualifying collective investment vehicles will be provided to you early next week. -

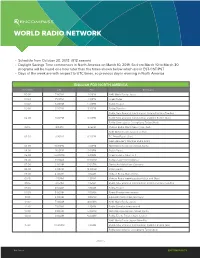

World Radio Network

WORLD RADIO NETWORK • Schedule from October 28, 2018 (B18 season) • Daylight Savings Time commences in North America on March 10, 2019. So from March 10 to March 30 programs will be heard one hour later than the times shown below which are in EST/CST/PST • Days of the week are with respect to UTC times, so previous day in evening in North America ENGLISH FOR NORTH AMERICA UTC/GMT EST PST Programs 00:00 7:00PM 4:00PM NHK World Radio Japan 00:30 7:30PM 4:30PM Israel Radio 01:00 8:00PM 5:00PM Radio Prague 00:30 8:30PM 5:30PM Radio Slovakia Radio New Zealand International: Korero Pacifica (Tue-Sat) 02:00 9:00PM 6:00PM Radio New Zealand International: Dateline Pacific (Sun) Radio Guangdong: Guangdong Today (Mon) 02:15 9:15PM 6:15PM Vatican Radio World News (Tue - Sat) NHK World Radio Japan (Tue-Sat) 02:30 9:30PM 6:30PM PCJ Asia Focus (Sun) Glenn Hauser’s World of Radio (Mon) 03:00 10:00PM 7:00PM KBS World Radio from Seoul, Korea 04:00 11:00PM 8:00PM Polish Radio 05:00 12:00AM 9:00PM Israel Radio – News at 8 06:00 1:00AM 10:00PM Radio France International 07:00 2:00AM 11:00PM Deutsche Welle from Germany 08:00 3:00AM 12:00AM Polish Radio 09:00 4:00AM 1:00AM Vatican Radio World News 09:15 4:15AM 1:15AM Vatican Radio weekly podcast (Sun and Mon) 09:15 4:15AM 1:15AM Radio New Zealand International: Korero Pacifica (Tue-Sat) 09:30 4:30AM 1:30AM Radio Prague 10:00 5:00AM 2:00AM Radio France International 11:00 6:00AM 3:00AM Deutsche Welle from Germany 12:00 7:00AM 4:00AM NHK World Radio Japan 12:30 7:30AM 4:30AM Radio Slovakia International 13:00 -

Download the Report

Oregon Cultural Trust fy2011 annual report fy2011 annual report 1 Contents Oregon Cultural Trust fy2011 annual report 4 Funds: fy2011 permanent fund, revenue and expenditures Cover photos, 6–7 A network of cultural coalitions fosters cultural participation clockwise from top left: Dancer Jonathan Krebs of BodyVox Dance; Vital collaborators – five statewide cultural agencies artist Scott Wayne 8–9 Indiana’s Horse Project on the streets of Portland; the Museum of 10–16 Cultural Development Grants Contemporary Craft, Portland; the historic Astoria Column. Oregonians drive culture Photographs by 19 Tatiana Wills. 20–39 Over 11,000 individuals contributed to the Trust in fy2011 oregon cultural trust board of directors Norm Smith, Chair, Roseburg Lyn Hennion, Vice Chair, Jacksonville Walter Frankel, Secretary/Treasurer, Corvallis Pamela Hulse Andrews, Bend Kathy Deggendorfer, Sisters Nick Fish, Portland Jon Kruse, Portland Heidi McBride, Portland Bob Speltz, Portland John Tess, Portland Lee Weinstein, The Dalles Rep. Margaret Doherty, House District 35, Tigard Senator Jackie Dingfelder, Senate District 23, Portland special advisors Howard Lavine, Portland Charlie Walker, Neskowin Virginia Willard, Portland 2 oregon cultural trust December 2011 To the supporters and partners of the Oregon Cultural Trust: Culture continues to make a difference in Oregon – activating communities, simulating the economy and inspiring us. The Cultural Trust is an important statewide partner to Oregon’s cultural groups, artists and scholars, and cultural coalitions in every county of our vast state. We are pleased to share a summary of our Fiscal Year 2011 (July 1, 2010 – June 30, 2011) activity – full of accomplishment. The Cultural Trust’s work is possible only with your support and we are pleased to report on your investments in Oregon culture. -

Review of Content Regulation Models

Issues facing broadcast content regulation MILLWOOD HARGRAVE LTD. Authors: Andrea Millwood Hargrave, Geoff Lealand, Paul Norris, Andrew Stirling Disclaimer The report is based on collaborative desk research conducted for the New Zealand Broadcasting Standards Authority over a two month period. Issue date November 2006 © Broadcasting Standards Authority, New Zealand Contents Aim and Scope of this Report..................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary.................................................................................................... 4 A: Introduction............................................................................................................. 6 Background............................................................................................................. 6 Definitions............................................................................................................... 9 What is the justification for regulation?.................................................................... 9 Protective content regulation: an overview............................................................ 10 Proactive content regulation: an overview............................................................. 12 Co-regulation and self-regulation........................................................................... 12 Technological changes and convergence.............................................................. 15 Differences in devices.......................................................................................... -

'About Turn': an Analysis of the Causes of the New Zealand Labour Party's

Newcastle University e-prints Date deposited: 2nd May 2013 Version of file: Author final Peer Review Status: Peer reviewed Citation for item: Reardon J, Gray TS. About Turn: An Analysis of the Causes of the New Zealand Labour Party's Adoption of Neo-Liberal Policies 1984-1990. Political Quarterly 2007, 78(3), 447-455. Further information on publisher website: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com Publisher’s copyright statement: The definitive version is available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-923X.2007.00872.x Always use the definitive version when citing. Use Policy: The full-text may be used and/or reproduced and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not for profit purposes provided that: A full bibliographic reference is made to the original source A link is made to the metadata record in Newcastle E-prints The full text is not changed in any way. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Robinson Library, University of Newcastle upon Tyne, Newcastle upon Tyne. NE1 7RU. Tel. 0191 222 6000 ‘About turn’: an analysis of the causes of the New Zealand Labour Party’s adoption of neo- liberal economic policies 1984-1990 John Reardon and Tim Gray School of Geography, Politics and Sociology Newcastle University Abstract This is the inside story of one of the most extraordinary about-turns in policy-making undertaken by a democratically elected political party. -

Mapping the Information Environment in the Pacific Island Countries: Disruptors, Deficits, and Decisions

December 2019 Mapping the Information Environment in the Pacific Island Countries: Disruptors, Deficits, and Decisions Lauren Dickey, Erica Downs, Andrew Taffer, and Heidi Holz with Drew Thompson, S. Bilal Hyder, Ryan Loomis, and Anthony Miller Maps and graphics created by Sue N. Mercer, Sharay Bennett, and Michele Deisbeck Approved for Public Release: distribution unlimited. IRM-2019-U-019755-Final Abstract This report provides a general map of the information environment of the Pacific Island Countries (PICs). The focus of the report is on the information environment—that is, the aggregate of individuals, organizations, and systems that shape public opinion through the dissemination of news and information—in the PICs. In this report, we provide a current understanding of how these countries and their respective populaces consume information. We map the general characteristics of the information environment in the region, highlighting trends that make the dissemination and consumption of information in the PICs particularly dynamic. We identify three factors that contribute to the dynamism of the regional information environment: disruptors, deficits, and domestic decisions. Collectively, these factors also create new opportunities for foreign actors to influence or shape the domestic information space in the PICs. This report concludes with recommendations for traditional partners and the PICs to support the positive evolution of the information environment. This document contains the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the sponsor or client. Distribution Approved for public release: distribution unlimited. 12/10/2019 Cooperative Agreement/Grant Award Number: SGECPD18CA0027. This project has been supported by funding from the U.S. -

Tvnz Teletext

TVNZ TELETEXT YOUR GUIDE TO TVNZ TELETEXT INFORMATION CONTENTS WELCOME TO TVNZ TELETEXT 3 TVNZ Teletext Has imProved 4 New PAGE GUIDE 5 NEW FUNCTIONS AND FEATURES 6 CAPTIONING 7 ABOUT TVNZ TELETEXT 8 HOW TO USE TVNZ TELETEXT 9-10 HISTORY OF TVNZ TELETEXT 11 FAQ 12-13 Contact detailS 14 WELCOME TO TVNZ TELETEXT It’s all available Your free service for up-to-the-minute news and information whenever you on your television need it – 24 hours a day, all year round. at the push of From news and sport to weather, a button travel, finance, TV listings and lifestyle information – it’s all available on your television, at the push of a button. 3 TVNZ Teletext Has imProved If you’ve looked at TVNZ Teletext recently and couldn’t find what you expected, don’t worry. To make the service easier and more logical to use we’ve reorganised a little. Your favourite content is still there – but in a different place. The reason is simple. We have a limited number of pages available, but need to show more information than ever. Previously, TVNZ Teletext had similar information spread across many pages unnecessarily. We’ve reorganised to keep similar pages together. For example, all news content is now grouped together, as is all sport content. You may also notice that the branding has changed slightly. Teletext is still owned and run by TVNZ, just as it always has been, we are now just reflecting this through the name - TVNZ Teletext. Now more than ever it will be a service that represents the integrity, neutrality and editorial independence you expect from New Zealand’s leading broadcaster. -

Download Download

New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 45(1): 14-30 Minor parties, ER policy and the 2020 election JULIENNE MOLINEAUX* and PETER SKILLING** Abstract Since New Zealand adopted the Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) representation electoral system in 1996, neither of the major parties has been able to form a government without the support of one or more minor parties. Understanding the ways in which Employment Relations (ER) policy might develop after the election, thus, requires an exploration of the role of the minor parties likely to return to parliament. In this article, we offer a summary of the policy positions and priorities of the three minor parties currently in parliament (the ACT, Green and New Zealand First parties) as well as those of the Māori Party. We place this summary within a discussion of the current volatile political environment to speculate on the degree of power that these parties might have in possible governing arrangements and, therefore, on possible changes to ER regulation in the next parliamentary term. Keywords: Elections, policy, minor parties, employment relations, New Zealand politics Introduction General elections in New Zealand have been held under the Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) system since 1996. Under this system, parties’ share of seats in parliament broadly reflects the proportion of votes that they received, with the caveat that parties need to receive at least five per cent of the party vote or win an electorate seat in order to enter parliament. The change to the MMP system grew out of increasing public dissatisfaction with certain aspects of the previous First Past the Post (FPP) or ‘winner-take-all’ system (NZ History, 2014). -

Alter Ego #78 Trial Cover

TwoMorrows Publishing. Celebrating The Art & History Of Comics. SAVE 1 NOW ALL WHE5% O N YO BOOKS, MAGS RDE U & DVD s ARE ONL R 15% OFF INE! COVER PRICE EVERY DAY AT www.twomorrows.com! PLUS: New Lower Shipping Rates . s r Online! e n w o e Two Ways To Order: v i t c e • Save us processing costs by ordering ONLINE p s e r at www.twomorrows.com and you get r i e 15% OFF* the cover prices listed here, plus h t 1 exact weight-based postage (the more you 1 0 2 order, the more you save on shipping— © especially overseas customers)! & M T OR: s r e t • Order by MAIL, PHONE, FAX, or E-MAIL c a r at the full prices listed here, and add $1 per a h c l magazine or DVD and $2 per book in the US l A for Media Mail shipping. OUTSIDE THE US , PLEASE CALL, E-MAIL, OR ORDER ONLINE TO CALCULATE YOUR EXACT POSTAGE! *15% Discount does not apply to Mail Orders, Subscriptions, Bundles, Limited Editions, Digital Editions, or items purchased at conventions. We reserve the right to cancel this offer at any time—but we haven’t yet, and it’s been offered, like, forever... AL SEE PAGE 2 DIGITIITONS ED E FOR DETAILS AVAILABL 2011-2012 Catalog To get periodic e-mail updates of what’s new from TwoMorrows Publishing, sign up for our mailing list! ORDER AT: www.twomorrows.com http://groups.yahoo.com/group/twomorrows TwoMorrows Publishing • 10407 Bedfordtown Drive • Raleigh, NC 27614 • 919-449-0344 • FAX: 919-449-0327 • e-mail: [email protected] TwoMorrows Publishing is a division of TwoMorrows, Inc. -

Mobile Is Theme for AUT University Jeanz Conference JTO Raises

Mobile is theme for AUT University Jeanz conference The Journalism Education Association of New Zealand annual conference will be held at AUT University, November 28-29, 2013. Conference theme: The Mobile Age or #journalism that won’t sit still. The ongoing disruption of ‘traditional’ journalism practice by digital technologies is encapsulated nowhere more succinctly than in the touch-screen mobile device still quaintly called a ‘telephone’. Growth in mobile consumption is strong as both consumers and journalists adjust to an age where no one needs to sit down for the news. Meanwhile, within the increasingly wireless network, participatory media continue to blur the lines around journalism. How should journalism educators respond? Presenters are invited to submit abstracts for either papers addressing the conference theme or non- themed papers by August 31, 2013. Papers requiring blind peer review must be with conference convenors by September 30, 2013. For all inquiries, please contact Greg Treadwell (gregory.treadwell@ aut.ac.nz) or Dr Allison Oosterman ([email protected]). Call for papers (PDF) Conference registration form: Word document or PDF Photo: The opening of AUT’s Sir Paul Reeves Building in March (Daniel Drageset/Pacific Media Centre) JTO raises concerns over media standards regulators The JTO has prepared a report analysing the Law Commission’s proposed reform of news media standards bodies. The JTO’s report identified three areas of concern: First, potential for rule cross-infection; ie tight restrictions that exist on some news media may be applied to all media. For instance, the BSA’s complex and rigid rules on privacy and children’s interests could be applied to other media. -

The Reflection of Sancho Panza in the Comic Book Sidekick De Don

UNIVERSIDAD DE OVIEDO FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS MEMORIA DE LICENCIATURA From Don Quixote to The Tick: The Reflection of Sancho Panza in the Comic Book Sidekick ____________ De Don Quijote a The Tick: El Reflejo de Sancho Panza en el sidekick del Cómic Autor: José Manuel Annacondia López Directora: Dra. María José Álvarez Faedo VºBº: Oviedo, 2012 To comic book creators of yesterday, today and tomorrow. The comics medium is a very specialized area of the Arts, home to many rare and talented blooms and flowering imaginations and it breaks my heart to see so many of our best and brightest bowing down to the same market pressures which drive lowest-common-denominator blockbuster movies and television cop shows. Let's see if we can call time on this trend by demanding and creating big, wild comics which stretch our imaginations. Let's make living breathing, sprawling adventures filled with mind-blowing images of things unseen on Earth. Let's make artefacts that are not faux-games or movies but something other, something so rare and strange it might as well be a window into another universe because that's what it is. [Grant Morrison, “Grant Morrison: Master & Commander” (2004: 2)] TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Acknowledgements v 2. Introduction 1 3. Chapter I: Theoretical Background 6 4. Chapter II: The Nature of Comic Books 11 5. Chapter III: Heroes Defined 18 6. Chapter IV: Enter the Sidekick 30 7. Chapter V: Dark Knights of Sad Countenances 35 8. Chapter VI: Under Scrutiny 53 9. Chapter VII: Evolve or Die 67 10.