Land & Natural Resource Management System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2854 ISS Monograph 130.Indd

FFROMROM SSOLDIERSOLDIERS TTOO CCITIZENSITIZENS THE SOCIAL, ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL REINTEGRATION OF UNITA EX-COMBATANTS J GOMES PORTO, IMOGEN PARSONS AND CHRIS ALDEN ISS MONOGRAPH SERIES • No 130, MARCH 2007 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii ABOUT THE AUTHORS v LIST OF ACRONYMS vi INTRODUCTION viii CHAPTER ONE 1 Angola’s Central Highlands: Provincial Characterisation and Fieldwork Review CHAPTER TWO 39 Unita’s Demobilised Soldiers: Portrait of the post-Luena target group CHAPTER THREE 53 The Economic, Social and Political Dimensions of Reintegration: Findings CHAPTER FOUR 79 Surveying for Trends: Correlation of Findings CHAPTER FIVE 109 From Soldiers to Citizens: Concluding Thoughts ENDNOTES 127 BIBLIOGRAPHY 139 ANNEX 145 Survey Questionnaire iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The research and publication of this monograph were made possible by the generous funding of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA), the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, and the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), through the African Security Analysis Programme at the ISS. The project “From Soldiers to Citizens: A study of the social, economic and political reintegration of UNITA ex-combatants in post-war Angola” was developed jointly by the African Security Analysis Programme at ISS, the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), and the Norwegian Institute for International Affairs (NUPI). In addition, the project established a number of partnerships with Angolan non-governmental organisations (NGOs), including Development -

Inventário Florestal Nacional, Guia De Campo Para Recolha De Dados

Monitorização e Avaliação de Recursos Florestais Nacionais de Angola Inventário Florestal Nacional Guia de campo para recolha de dados . NFMA Working Paper No 41/P– Rome, Luanda 2009 Monitorização e Avaliação de Recursos Florestais Nacionais As florestas são essenciais para o bem-estar da humanidade. Constitui as fundações para a vida sobre a terra através de funções ecológicas, a regulação do clima e recursos hídricos e servem como habitat para plantas e animais. As florestas também fornecem uma vasta gama de bens essenciais, tais como madeira, comida, forragem, medicamentos e também, oportunidades para lazer, renovação espiritual e outros serviços. Hoje em dia, as florestas sofrem pressões devido ao aumento de procura de produtos e serviços com base na terra, o que resulta frequentemente na degradação ou transformação da floresta em formas insustentáveis de utilização da terra. Quando as florestas são perdidas ou severamente degradadas. A sua capacidade de funcionar como reguladores do ambiente também se perde. O resultado é o aumento de perigo de inundações e erosão, a redução na fertilidade do solo e o desaparecimento de plantas e animais. Como resultado, o fornecimento sustentável de bens e serviços das florestas é posto em perigo. Como resposta do aumento de procura de informações fiáveis sobre os recursos de florestas e árvores tanto ao nível nacional como Internacional l, a FAO iniciou uma actividade para dar apoio à monitorização e avaliação de recursos florestais nationais (MANF). O apoio à MANF inclui uma abordagem harmonizada da MANF, a gestão de informação, sistemas de notificação de dados e o apoio à análise do impacto das políticas no processo nacional de tomada de decisão. -

Angolan National Report for Habitat III

Republic of Angola NATIONAL HABITAT COMMITTEE Presidential Decree no. 18/14, of 6 of March Angolan National Report for Habitat III On the implementation of the Habitat II Agenda Under the Coordination of the Ministry of Urban Development and Housing with support from Development Workshop Angola Luanda – June 2014 Revised - 11 March 2016 Angola National Report for Habitat III March 2016 2 Angola National Report for Habitat III March 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 11 II. URBAN DEMOGRAPHIC ISSUES ............................................................................................... 12 1. Migration and rapid urbanisation ...................................................................................... 12 Urban Population Growth ............................................................................................ 12 Drivers of Migration ...................................................................................................... 14 2. Rural-urban linkages........................................................................................................... 16 3. Addressing urban youth needs .......................................................................................... 17 4. Responding to the needs of the elderly ............................................................................. 19 5. Integrating gender in urban development ........................................................................ -

VI. O Acto Eleitoral

VI. O acto eleitoral No dia 5 de Setembro de 2008, em todas as Províncias do país, os angolanos levantaram-se cedo para exercerem o seu direito de voto. Infelizmente, cedo se descobriu que não seriam essas as eleições que se esperava viessem a ser exemplares para o Continente Africano e para o Mundo. Eis aqui um resumo das ocorrências fraudulentas que, em 5 de Setembro de 2008, caracterizaram o dia mais esperado do processo político, o dia D: 1. Novo mapeamento das Assembleias de Voto 1.1 O mapeamento inicialmente distribuído aos Partidos Políticos, assim como os locais de funcionamento das Assembleias de Voto e os cadernos de registo eleitoral, não foram publicitados com a devida antecedência, para permitir uma eleição ordeira e organizada. 1.2 Para agravar a situação, no dia da votação, o mapeamento dos locais de funcionamento das Assembleias de Voto produzido pela CNE não foi o utilizado. O mapeamento utilizado foi outro, produzido por uma instituição de tal modo estranha à CNE e que os próprios órgãos locais da CNE desconheciam. Em resultado, i. Milhares de eleitores ficaram sem votar; ii. Aldeias e outras comunidades tiveram de ser arregimentadas em transportes arranjados pelo Governo, para irem votar em condições de voto condicionado; iii. Não houve mecanismos fiáveis de controlo da observância dos princípios da universalidade e da unicidade do voto. 1.3 O Nº. 2 do Art.º 105 da Lei Eleitoral é bastante claro: “a constituição das Mesas fora dos respectivos locais implica a nulidade das eleições na Mesa em causa e das operações eleitorais praticadas nessas circunstâncias, salvo motivo de força maior, devidamente justificado e apreciado pelas instâncias judiciais competentes ou por acordo escrito entre a entidade municipal da Comissão Nacional Eleitoral e os delegados dos partidos políticos e coligações de partidos ou dos candidatos concorrentes.” 1.4 Em todos os casos que a seguir se descreve, foram instaladas Assembleias de Voto anteriormente não previstas. -

31 CFR Ch. V (7–1–05 Edition) Pt. 590, App. B

Pt. 590, App. B 31 CFR Ch. V (7–1–05 Edition) (2) Pneumatic tire casings (excluding tractor (C) Nharea and farm implement types), of a kind (2) Communities: specially constructed to be bulletproof or (A) Cassumbe to run when deflated (ECCN 9A018); (B) Chivualo (3) Engines for the propulsion of the vehicles (C) Umpulo enumerated above, specially designed or (D) Ringoma essentially modified for military use (E) Luando (ECCN 9A018); and (F) Sachinemuna (4) Specially designed components and parts (G) Gamba to the foregoing (ECCN 9A018); (H) Dando (f) Pressure refuellers, pressure refueling (I) Calussinga equipment, and equipment specially de- (J) Munhango signed to facilitate operations in con- (K) Lubia fined areas and ground equipment, not (L) Caleie elsewhere specified, developed specially (M) Balo Horizonte for aircraft and helicopters, and specially (b) Cunene Province: designed parts and accessories, n.e.s. (1) Municipalities: (ECCN 9A018); [Reserved] (g) Specifically designed components and (2) Communities: parts for ammunition, except cartridge (A) Cubati-Cachueca cases, powder bags, bullets, jackets, (B) [Reserved] cores, shells, projectiles, boosters, fuses (c) Huambo Province: and components, primers, and other det- (1) Municipalities: onating devices and ammunition belting (A) Bailundo and linking machines (ECCN 0A018); (B) Mungo (h) Nonmilitary shotguns, barrel length 18 (2) Communities: inches or over; and nonmilitary arms, (A) Bimbe discharge type (for example, stun-guns, (B) Hungue-Calulo shock batons, etc.), except arms designed (C) Lungue solely for signal, flare, or saluting use; (D) Luvemba and parts, n.e.s. (ECCNs 0A984 and 0A985); (E) Cambuengo (i) Shotgun shells, and parts (ECCN 0A986); (F) Mundundo (j) Military parachutes (ECCN 9A018); (G) Cacoma (k) Submarine and torpedo nets (ECCN (d) K. -

Mapa Rodoviario Angola

ANGOLA REPÚBLICA DE ANGOLA MINISTÉRIO DAS FINANÇAS FUNDO RODOVIÁRIO Miconje ANGOLA Luali EN 220 Buco Zau Belize Inhuca Massabi EN 220 Necuto Dinge O Chicamba ANG LU O EN 101 EN 100 I R CABINDA Bitchequete Cacongo Zenza de Lucala Malembo Fubo EN 100 EN 201 CABINDA Cabassango Noqui Luvo Pedra do Buela EN 210 Feitiço EN 120 EN 210 Sacandica Lulendo Maquela Sumba ZAIRE Cuimba do Zombo Icoca Soyo Béu EN 160 Cuango Lufico M´BANZA Quimbocolo Canda Cuilo Futa Quiende CONGO EN 140 Quimbele Quielo Camboso EN 210 Mandimba Sacamo Camatambo Quincombe Fronteira EN 120 Damba Quiximba Lucunga Lemboa Buengas Santa Tomboco 31 de Janeiro Quinzau EN 160 RIO BRIDG Cruz M E Quimbianda Uambo EN 100 Bessa Bembe Zenguele UIGE Macocola Macolo Monteiro Cuilo Pombo N´Zeto EN 120 Massau Tchitato Mabaia Mucaba Sanza Uamba EN 223 E EN 223 OG O L EN 140 Quibala Norte RI Songo Pombo Lovua Ambuíla Bungo Alfândega DUNDO EN 220 EN 220 Quinguengue EN 223 Musserra UÍGE Puri EN 180 Canzar Desvio do Cagido Caiongo Quihuhu Cambulo Quipedro EN 120 Negage EN 160 Zala Entre os Rios Ambriz Bela Dange EN 220 Vista Gombe Quixico Aldeia Quisseque Cangola EN 140 Mangando EN 225 EN 100 MuxaluandoViçosa Bindo Massango BENGO Tango MALANGE Camissombo Luia Canacassala Cambamba Bengo EN 165 Caluango Tabi Quicunzo Cabombo Cuilo Quicabo Vista Quiquiemba Camabatela Cuale EN 225 Ramal da Barra Cage Alegre Maua Caungula Camaxilo Capaia Cachimo DANDE do Dande Libongos O RI S. J.das Terreiro EN 225 Barra do BolongongoLuinga Marimba Luremo Quibaxe Matas Cateco Micanda Lucapa Dande Mabubas EN 225 -

Dotação Orçamental Por Orgão

Exercício : 2021 Emissão : 17/12/2020 Página : 158 DOTAÇÃO ORÇAMENTAL POR ORGÃO Órgão: Assembleia Nacional RECEITA POR NATUREZA ECONÓMICA Natureza Valor % Total Geral: 130.000.000,00 100,00% Receitas Correntes 130.000.000,00 100,00% Receitas Correntes Diversas 130.000.000,00 100,00% Outras Receitas Correntes 130.000.000,00 100,00% DESPESAS POR NATUREZA ECONÓMICA Natureza Valor % Total Geral: 34.187.653.245,00 100,00% Despesas Correntes 33.787.477.867,00 98,83% Despesas Com O Pessoal 21.073.730.348,00 61,64% Despesas Com O Pessoal Civil 21.073.730.348,00 61,64% Contribuições Do Empregador 1.308.897.065,00 3,83% Contribuições Do Empregador Para A Segurança Social 1.308.897.065,00 3,83% Despesas Em Bens E Serviços 10.826.521.457,00 31,67% Bens 2.520.242.794,00 7,37% Serviços 8.306.278.663,00 24,30% Subsídios E Transferências Correntes 578.328.997,00 1,69% Transferências Correntes 578.328.997,00 1,69% Despesas De Capital 400.175.378,00 1,17% Investimentos 373.580.220,00 1,09% Aquisição De Bens De Capital Fixo 361.080.220,00 1,06% Compra De Activos Intangíveis 12.500.000,00 0,04% Outras Despesas De Capital 26.595.158,00 0,08% DESPESAS POR FUNÇÃO Função Valor % Total Geral: 34.187.653.245,00 100,00% Serviços Públicos Gerais 34.187.653.245,00 100,00% Órgãos Legislativos 34.187.653.245,00 100,00% DESPESAS POR PROGRAMA Programa / Projecto Valor % Total Geral: 34.187.653.245,00 100,00% Acções Correntes 33.862.558.085,00 99,05% Operação E Manutenção Geral Dos Serviços 10.567.385.159,00 Administração Geral 22.397.811.410,00 Manutenção Das Relações -

Chapter 15 the Mammals of Angola

Chapter 15 The Mammals of Angola Pedro Beja, Pedro Vaz Pinto, Luís Veríssimo, Elena Bersacola, Ezequiel Fabiano, Jorge M. Palmeirim, Ara Monadjem, Pedro Monterroso, Magdalena S. Svensson, and Peter John Taylor Abstract Scientific investigations on the mammals of Angola started over 150 years ago, but information remains scarce and scattered, with only one recent published account. Here we provide a synthesis of the mammals of Angola based on a thorough survey of primary and grey literature, as well as recent unpublished records. We present a short history of mammal research, and provide brief information on each species known to occur in the country. Particular attention is given to endemic and near endemic species. We also provide a zoogeographic outline and information on the conservation of Angolan mammals. We found confirmed records for 291 native species, most of which from the orders Rodentia (85), Chiroptera (73), Carnivora (39), and Cetartiodactyla (33). There is a large number of endemic and near endemic species, most of which are rodents or bats. The large diversity of species is favoured by the wide P. Beja (*) CIBIO-InBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Universidade do Porto, Vairão, Portugal CEABN-InBio, Centro de Ecologia Aplicada “Professor Baeta Neves”, Instituto Superior de Agronomia, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal e-mail: [email protected] P. Vaz Pinto Fundação Kissama, Luanda, Angola CIBIO-InBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Universidade do Porto, Campus de Vairão, Vairão, Portugal e-mail: [email protected] L. Veríssimo Fundação Kissama, Luanda, Angola e-mail: [email protected] E. -

Dotacao Orcamental Por Orgao

Exercício : 2021 Emissão : 30/10/2020 Página : 155 DOTAÇÃO ORÇAMENTAL POR ORGÃO Órgão: Assembleia Nacional DESPESAS POR NATUREZA ECONÓMICA Natureza Valor % Total Geral: 34.187.653.245,00 100,00% Despesas Correntes 33.787.477.867,00 98,83% Despesas Com O Pessoal 21.073.730.348,00 61,64% Despesas Com O Pessoal Civil 21.073.730.348,00 61,64% Contribuições Do Empregador 1.308.897.065,00 3,83% Contribuições Do Empregador Para A Segurança Social 1.308.897.065,00 3,83% Despesas Em Bens E Serviços 10.826.521.457,00 31,67% Bens 2.520.242.794,00 7,37% Serviços 8.306.278.663,00 24,30% Subsídios E Transferências Correntes 578.328.997,00 1,69% Transferências Correntes 578.328.997,00 1,69% Despesas De Capital 400.175.378,00 1,17% Investimentos 373.580.220,00 1,09% Aquisição De Bens De Capital Fixo 361.080.220,00 1,06% Compra De Activos Intangíveis 12.500.000,00 0,04% Outras Despesas De Capital 26.595.158,00 0,08% DESPESAS POR FUNÇÃO Função Valor % Total Geral: 34.187.653.245,00 100,00% Serviços Públicos Gerais 34.187.653.245,00 100,00% Órgãos Legislativos 34.187.653.245,00 100,00% DESPESAS POR PROGRAMA Programa / Projecto Valor % Total Geral: 34.187.653.245,00 100,00% Acções Correntes 33.862.558.085,00 99,05% Operação E Manutenção Geral Dos Serviços 10.567.385.159,00 Administração Geral 22.397.811.410,00 Manutenção Das Relações Bilaterais E Organizações Multilaterais 764.164.343,00 Encargos Com A Comissão Da Carteira E Ética 133.197.173,00 Combate Às Grandes Endemias Pela Abordagem Das Determinantes Da Saúde 325.095.160,00 0,95% Comissão Multissectorial -

S Angola on Their Way South

Important Bird Areas in Africa and associated islands – Angola ■ ANGOLA W. R. J. DEAN Dickinson’s Kestrel Falco dickinsoni. (ILLUSTRATION: PETE LEONARD) GENERAL INTRODUCTION December to March. A short dry period during the rains, in January or February, occurs in the north-west. The People’s Republic of Angola has a land-surface area of The cold, upwelling Benguela current system influences the 1,246,700 km², and is bounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the west, climate along the south-western coast, and this region is arid in the Republic of Congo to the north-west, the Democratic Republic of south to semi-arid in the north (at about Benguela). Mean annual Congo (the former Zaïre) to the north, north-east, and east, Zambia temperatures in the region, and on the plateau above 1,600 m, are to the south-east, and Namibia to the south. It is divided into 18 below 19°C. Areas with mean annual temperatures exceeding 25°C (formerly 16) administrative provinces, including the Cabinda occur on the inner margin of the Coast Belt north of the Queve enclave (formerly known as Portuguese Congo) that is separated river and in the Congo Basin (Huntley 1974a). The hottest months from the remainder of the country by a narrow strip of the on the coast are March and April, during the period of heaviest Democratic Republic of Congo and the Congo river. rains, but the hottest months in the interior, September and October, The population density is low, c.8.5 people/km², with a total precede the heaviest rains (Huntley 1974a). -

Government of the Republic of Angola

New Partnership for Food and Agriculture Organization Africa’s Development (NEPAD) of the United Nations Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Investment Centre Division Development Programme (CAADP) GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF ANGOLA SUPPORT TO NEPAD–CAADP IMPLEMENTATION TCP/ANG/2908 (I) (NEPAD Ref. 05/15 E) Volume V of VI BANKABLE INVESTMENT PROJECT PROFILE Revitalization of Angola Forestry Sector December 2005 ANGOLA: Support to NEPAD–CAADP Implementation Volume I: National Medium–Term Investment Programme (NMTIP) Bankable Investment Project Profiles (BIPPs) Volume II: Irrigation Rehabilitation and Sustainable Water Resources Management Volume III: Rehabilitation of Rural Marketing and Agro–Processing Infrastructures Volume IV: Agricultural Research and Extension Volume V: Revitalization of Angola Forestry Sector Volume VI: Integrated Support Centres for Artisanal Fisheries NEPAD–CAADP BANKABLE INVESTMENT PROJECT PROFILE Country: Angola Sector of Activities: Forestry Proposed Project Name: Revitalization of Angola Forestry Sector Project Area: Selected Regions of Angola Duration of Project: 5 years Estimated Cost: Foreign Exchange...............US$44.2 million Local Cost...........................US$30.6 million Total ...................................US$74.8 million Suggested Financing: Source US$ million % of total Government 8.8 12 Financing institution(s) 44.2 59 Private sector 21.8 29 Total 74.8 100 ANGOLA: NEPAD–CAADP Bankable Investment Project Profile “Revitalization of Angola Forestry Sector” Table of Contents Abbreviations....................................................................................................................................... -

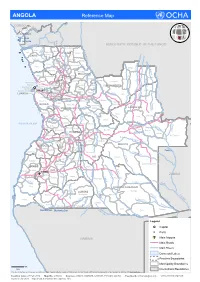

ANGOLA Reference Map

ANGOLA Reference Map CONGO L Belize ua ng Buco Zau o CABINDA Landana Lac Nieba u l Lac Vundu i Cabinda w Congo K DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO o z Maquela do Zombo o p Noqui e Kuimba C Soyo M Mbanza UÍGE Kimbele u -Kongo a n ZAIRE e Damba g g o id Tomboco br Buengas M Milunga I n Songo k a Bembe i C p Mucaba s Sanza Pombo a i a u L Nzeto c u a i L l Chitato b Uige Bungo e h o e d C m Ambuila g e Puri Massango b Negage o MALANGE L Ambriz Kangola o u Nambuangongo b a n Kambulo Kitexe C Ambaca m Marimba g a Kuilo Lukapa h u Kuango i Kalandula C Dande Bolongongo Kaungula e u Sambizanga Dembos Kiculungo Kunda- m Maianga Rangel b Cacuaco Bula-Atumba Banga Kahombo ia-Baze LUNDA NORTE e Kilamba Kiaxi o o Cazenga eng Samba d Ingombota B Ngonguembo Kiuaba n Pango- -Caju a Saurimo Barra Do Cuanza LuanCda u u Golungo-Alto -Nzoji Viana a Kela L Samba Aluquem Lukala Lul o LUANDA nz o Lubalo a Kazengo Kakuso m i Kambambe Malanje h Icolo e Bengo Mukari c a KWANZA-NORTE Xa-Muteba u Kissama Kangandala L Kapenda- L Libolo u BENGO Mussende Kamulemba e L m onga Kambundi- ando b KWANZA-SUL Lu Katembo LUNDA SUL e Kilenda Lukembo Porto Amboim C Kakolo u Amboim Kibala t Mukonda Cu a Dala Luau v t o o Ebo Kirima Konda Ca s Z ATLANTIC OCEAN Waco Kungo Andulo ai Nharea Kamanongue C a Seles hif m um b Sumbe Bailundo Mungo ag e Leua a z Kassongue Kuemba Kameia i C u HUAMBO Kunhinga Luena vo Luakano Lobito Bocoio Londuimbali Katabola Alto Zambeze Moxico Balombo Kachiungo Lun bela gue-B Catum Ekunha Chinguar Kuito Kamakupa ungo a Benguela Chinjenje z Huambo n MOXICO