Vol 9 2 2018.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Didactic Fragmentation in ''Scenes from the Big Picture'

Didactic Fragmentation in ”Scenes from the Big Picture” (2003) by Owen McCafferty Virginie Privas-Bréauté To cite this version: Virginie Privas-Bréauté. Didactic Fragmentation in ”Scenes from the Big Picture” (2003) by Owen McCafferty. 2012. halshs-01071477 HAL Id: halshs-01071477 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01071477 Preprint submitted on 5 Oct 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. !1 Didactic Fragmentation in Scenes from the Big Picture (2003) by Owen McCafferty Virginie Privas-Bréauté Université Jean Moulin - Lyon 3 Brecht’s dramatic theory helps demonstrate that the contours of contemporary Northern Irish drama have been reshaped. In this respect, Owen McCafferty’s play Scenes from the Big Picture has Neo-Brechtian resonances. The audience is presented with frag- ments of lives of people, bits and pieces of a whole picture. This play exemplifies Brecht’s idea of a didactic play in so far as the audience is called to learn about the Northern Irish Troubles from the play through the device of fragmentation: the uneven background of McCafferty’s play – i.e. the Troubles – is peopled with traumatised indi- viduals, proportionally fragmented. -

The Theatre of the Real Yeats, Beckett, and Sondheim

The Theatre of the Real MMackenzie_final4print.indbackenzie_final4print.indb i 99/16/2008/16/2008 55:40:32:40:32 PPMM MMackenzie_final4print.indbackenzie_final4print.indb iiii 99/16/2008/16/2008 55:40:50:40:50 PPMM The Theatre of the Real Yeats, Beckett, and Sondheim G INA MASUCCI MACK ENZIE THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS • COLUMBUS MMackenzie_final4print.indbackenzie_final4print.indb iiiiii 99/16/2008/16/2008 55:40:50:40:50 PPMM Copyright © 2008 by Th e Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data MacKenzie, Gina Masucci. Th e theatre of the real : Yeats, Beckett, and Sondheim / Gina Masucci MacKenzie. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978–0–8142–1096–3 (cloth : alk. paper)—ISBN 978–0–8142–9176–4 (cd-rom) 1. English drama—Irish authors—History and criticism—Th eory, etc. 2. Yeats, W. B. (William Butler), 1865–1939—Dramatic works. 3. Beckett, Samuel, 1906–1989—Dramatic works. 4. Sondheim, Stephen—Criticism and interpretation. 5. Th eater—United States—History— 20th century. 6. Th eater—Great Britain—History—20th century. 7. Ireland—Intellectual life—20th century. 8. United States—Intellectual life—20th century. I. Title. PR8789.M35 2008 822.009—dc22 2008024450 Th is book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978–0–8142–1096–3) CD-ROM (ISBN 978–0–8142–9176–4) Cover design by Jason Moore. Text design by Jennifer Forsythe. Typeset in Adobe Minion Pro. Printed by Th omson-Shore, Inc. Th e paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. -

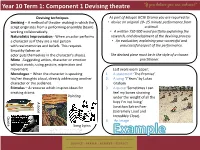

Year 10 Term 1: Component 1 Devising Theatre

Year 10 Term 1: Component 1 Devising theatre Devising techniques As part of Eduqas GCSE Drama you are required to: Devising – A method of theatre- making in which the • devise an original 10- 15 minute performance from script originates from a performing ensemble (team) a stimuli working collaboratively. • A written 750-900 word portfolio explaining the Naturalistic Improvisation - When an actor performs research, and development of the devising process. a character as if they are a real person • An evaluation, explaining your successful and with real memories and beliefs. This requires unsuccessful aspect of the performance. Empathy (when an actor puts themselves in the character’s shoes). The devised piece must be in the style of a chosen Mime -Suggesting action, character or emotion practitioner. without words, using gesture, expression and movement. Last years exam paper: Monologue – When the character is speaking 1. A statement ‘The Promise’ his/her thoughts aloud, directly addressing another 2. A song ‘7 Years’ by Lukas character or the audience. Graham Stimulus – A recourse which inspires ideas for 3. A quote ‘Sometimes I can creating drama. feel my bones straining Painting under the weight of all the A book lives I’m not living’ Jonathan Safran Foer (Extremely Loud and Quote Incredibly Close). 4. An Image Song Lyrics Year 10 Term 1: Component 1 Devising Theatre Research- Explore each stimuli, finding out all the A sequence in a chronological order fact around it. including a beginning, middle and end. Map ideas – Write all your initial ideas on a mind map. Discuss – Share your ideas with your group and decide on a final idea. -

Programming; Providing an Environment for the Growth and Education of Theatre Professionals, Audiences, and the Community at Large

JULY 2017 WELCOME MIKE HAUSBERG Welcome to The Old Globe and this production of King Richard II. Our goal is to serve all of San Diego and beyond through the art of theatre. Below are the mission and values that drive our work. We thank you for being a crucial part of what we do. MISSION STATEMENT The mission of The Old Globe is to preserve, strengthen, and advance American theatre by: creating theatrical experiences of the highest professional standards; producing and presenting works of exceptional merit, designed to reach current and future audiences; ensuring diversity and balance in programming; providing an environment for the growth and education of theatre professionals, audiences, and the community at large. STATEMENT OF VALUES The Old Globe believes that theatre matters. Our commitment is to make it matter to more people. The values that shape this commitment are: TRANSFORMATION Theatre cultivates imagination and empathy, enriching our humanity and connecting us to each other by bringing us entertaining experiences, new ideas, and a wide range of stories told from many perspectives. INCLUSION The communities of San Diego, in their diversity and their commonality, are welcome and reflected at the Globe. Access for all to our stages and programs expands when we engage audiences in many ways and in many places. EXCELLENCE Our dedication to creating exceptional work demands a high standard of achievement in everything we do, on and off the stage. STABILITY Our priority every day is to steward a vital, nurturing, and financially secure institution that will thrive for generations. IMPACT Our prominence nationally and locally brings with it a responsibility to listen, collaborate, and act with integrity in order to serve. -

The Role of the Theatre Audience: a Theory of Production and Reception

THE ROLE OF THE THEATRE AUDIENCE THE ROLE OF THE THEATRE AUDIENCE: A THEORY OF PRODUCTION AND RECEPTION By SUSAN BENNETT, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Parial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University January 1988 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (1988) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (English) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: The Role of the Theatre Audience: A Theory of Production and Reception AUTHOR: Susan Bennett, B.A. (University of Kent at Canterbury) M.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Dr. Linda Hutcheon NUMBER OF PAGES: viii, 389 ii ABSTRACT Th thesis examines the reception of theatrical performanc by their audience. Its starting points are (i) Brech s dramatic theory and practice, and (ii) theories 0 reading. These indicate the main emphases of the th ,is--theoretical approaches and performance practices, rather than the more usual recourse to dramatic ;xts. Beyond Brecht and reader-response criticism, other studies of viewing are explored. Both semiotics lnd post-structuralism have stimulated an intensity )f interest in theatrical communication and such inves ~gations provide an important impetus for my work. In suggesting a theory of reception in the theatre, examine _theatre's cultural status and the assumption underlying what we recognize as the theatrical event. The selection of a particular performanc is explored and from this, it is suggested that there _s an inevitable, inextricable link between the produc ~ve and receptive processes. The theory then looks to lore immediate aspects of the performance, including 1e theatre building (its geographic location, architectu 11 style, etc.), the performance itself, and the post-p :formance rituals of theatre-going. -

Wojciechowski 1 Study Guide for Epic Theatre, Bertolt Brecht, the Theatre

Wojciechowski 1 Study Guide for Epic Theatre, Bertolt Brecht, the Theatre of the Absurd, and Friedrich Dürrenmatt 1. Define Epic Theatre. Theatrical movement from the early to mid-twentieth century that responded to the political climate of the time to a new political theater Erwin Piscator – German theater director Encouraged playwrights to address issues related to “contemporary existence” Staging: documentary effects (projections on screens), audience interaction, use of chorus The Epic Theatre was a reaction against the psychological realism in writing and staging associated with playwrights like Henrik Ibsen. At the same time, it recalls techniques employed by the Classical Greeks, like Euripides. One of the goals of Epic Theatre was to remove the audience from being emotionally involved in the characters so that they could respond and be moved to action by the message of the play. This involved a practice called verfremdungseffekt. 2. What is verfremdungseffekt? A. B. C. D. Why? 3. Some theatrical techniques (technical/performance) to achieve verfremdungseffekt: A. i. Origin: Classical theater B. i. Origin: Classical theater Wojciechowski 2 ii. long soliloquies that are narrative and self-revelatory C. i. light the house as well as the stage ii. place lighting equipment on the stage D. i. play characters believably without convincing either themselves or the audience that they have “become” the characters 4. Some dramatic techniques to achieve verfremdungseffekt: A. B. i. Notes describe minimalistic staging. ii. Stage directions do not describe psychological characterization – only physical. C. D. E. F. 5. The Epic Theatre movement was most developed by Bertolt Brecht; who is he? A. -

Chapter One a Theoretical Background to the Figure of The

19 Chapter One A Theoretical Background to the figure of the Artist in Literature and Theatre In an article published in Fall 2009, Csilla Bertha maintains that the central place an artist occupies within a work of art adds an additional dimension to plays, since the fictional artist’s point of view, attitudes to the world and evaluation of phenomena, may double or multiply the layers of the connections between art and life. She then adds: If an artist is chosen to be the protagonist of a play or novel, that choice naturally leads to the thematization of questions and dilemmas about the existence of art and the artist; relations between art and life, art/artist and the world; the nature of artistic creation; differences between ways of life, values, and views of ordinary people and artists; relations between individual and community, between the subject and objective reality; and many other similar issues.1 No doubt, with the advent of highly sophisticated and challenging notions such as Formalism2 and the death of the author,3 it is hard to conceive the figure of the artist without paying attention to the interrelations between art and life in which the ideal and reality, subject and object, constitute sharp contrasts. Traditionally, this dialectical relationship forms “binary 1 Csilla Bertha, “Visual Art and Artist in Contemporary Irish Drama”, Hungarian Journal of English and American Studies (HJEAS) v. 15, no. 2 (Fall 2009): 347. 2 Formalism is a Russian literary movement which originated in the second decade of the twentieth century. Its leading figures were both linguists and literary historians such as Boris Eikhenbaum (1886-1959), Roman Jakobson (1895-1982), Viktor Shklovsky (1893-1984), Boris Tomashevskij (1890-1957) and Jurij Tynjanov (1894-1943). -

Modern Drama: an Overview

Tikrit University College of Education English Department Modern Drama Dr. Awfa Hussein Al-Doory, PhD Modern Drama: An Overview The birth of modern drama dates back to the 20th century which encompasses different playwright with different styles and techniques. The age of modern drama is an age of (isms) that is the emergence of different literary schools which influence the way subject matters are tackled and represented. One of the most common features of modern drama is that of realism. Earlier years of the 20th century witnessed an interest in realistic tendency which endeavors to deal and reflect on real problems of life. Modern drama, in this sense, aims at presenting life as it is. It was Henrik Ibsen, the Norwegian playwright, who popularized realism and drama of ideas in modern theatre. As a realist playwright, Ibsen employs theatre as a means for tackling realistic subject matters like marriage, justice, law, social conflicts, and the like; he (Ibsen) is significantly considered a social reformer because of tackling such realistic subject matters. Ibsen's play A Doll's House is a good example of realistic drama. Naturalism is an extreme realism. This movement suggested the roles of family, social conditions, and environment in shaping human character. Thus, naturalistic writers write stories based on the idea that environmental forces determine man's fate and make him act and react in a particular way. Generally, naturalistic works expose dark sides of life such as prejudice, racism, poverty, prostitution, filth, and disease. Despite the echoing pessimism in this literary output, naturalists are generally concerned with improving human conditions around the world. -

Two Tendencies Beyond Realism in Arthur Miller's Dramatic Works

Inês Evangelista Marques 2º Ciclo de Estudos em Estudos Anglo-Americanos, variante de Literaturas e Culturas The Intimate and the Epic: Two Tendencies beyond Realism in Arthur Miller’s Dramatic Works A critical study of Death of a Salesman, A View from the Bridge, After the Fall and The American Clock 2013 Orientador: Professor Doutor Rui Carvalho Homem Coorientador: Professor Doutor Carlos Azevedo Classificação: Ciclo de estudos: Dissertação/relatório/Projeto/IPP: Versão definitiva 2 Abstract Almost 65 years after the successful Broadway run of Death of a Salesman, Arthur Miller is still deemed one of the most consistent and influential playwrights of the American dramatic canon. Even if his later plays proved less popular than the early classics, Miller’s dramatic output has received regular critical attention, while his long and eventful life keeps arousing the biographers’ curiosity. However, most of the academic works on Miller’s dramatic texts are much too anchored on a thematic perspective: they study the plays as deconstructions of the American Dream, as a rebuke of McCarthyism or any kind of political persecution, as reflections on the concepts of collective guilt and denial in relation to traumatizing events, such as the Great Depression or the Holocaust. Especially within the Anglo-American critical tradition, Miller’s plays are rarely studied as dramatic objects whose performative nature implies a certain range of formal specificities. Neither are they seen as part of the 20th century dramatic and theatrical attempts to overcome the canons of Realism. In this dissertation, I intend, first of all, to frame Miller’s dramatic output within the American dramatic tradition. -

Is Theatre Under Deconstruction? a Retroactive Manifesto in a Language I Do Not Own

Fall 1989 31 Is Theatre Under Deconstruction? A Retroactive Manifesto in a Language I Do Not Own Stratos E. Constantinidis Hebraism and Hellenism—between these two points of influence moves our world. At one time it feels more powerfully the attraction of one of them, at another time of the other. Matthew Arnold, Culture and Anarchy Are we Jews? Are we Greeks? We live in the difference between the Jew and the Greek, which is perhaps the unity of what is called history. We live in and of difference, that is, in hypocrisy. Jacques Derrida, Writing and Difference Where's the Beef? Like all western theatre artists, I have two good friends, a Jew and a Greek, who are not very kind to each other: the Greek works in a theatre on Stratos E. Constantinidis teaches dramatic theory and criticism in the Department of Theatre at the Ohio State University. He has contributed articles to Poetics Today (Israel), Comparative Drama (U.S.A.), New Theatre Quarterly (England), Journal of Modern Greek Studies (U.S.A.), Code / Kodikas: Ars Semeiotica (West Germany), Theater Studies (U.SA.) and World Literature Today. 32 Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism Broadway while the Jew in a theatre off Broadway. When they lived in London a couple of years ago, the Greek was employed in a theatre on the West End; the Jew in a theatre on the "Fringe." In fact, the Greek always occupied the center of theatrical activity and the Jew the periphery in every capital of the western world that they worked. -

Re-Imagining Political Theatre for the Twenty‐First Century

Re-imagining political theatre for the twenty-first century By Leticia Caceres Submitted in total fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Masters of Fine Arts - Theatre direction (by Research) November 2012 Department of Performing Arts Victorian Collage of the Arts The University of Melbourne TABLE OF CONTENTS RE-IMAGINING POLITICAL THEATRE FOR THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY 1 ABSTRACT I DECLARATION II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS IV INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1 7 LITERATURE REVIEW 7 MODERNISM AND POLITICAL THEATRE 9 DEFINITIONS OF ‘POLITICAL’ IN THE POSTMODERN AGE 9 POST – BRECHT? 11 AN ARGUMENT FOR ‘ROUGH’ THEATRE IN A TECHNOLOGICALLY DRIVEN WORLD 13 IMAGINATION IN THE AGE OF GLOBALIZATION 14 THEATRE FOR RESISTANCE IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY 16 CHAPTER 2 19 POLITICAL THEATRE IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY – GLOBALIZATION, COSMOPOLITANISM, THEATRICAL PRACTICE 19 THE ETHICS OF GLOBAL – CAPITALISM 19 COSMOPOLITANISM 21 THE ROOTS OF COSMOPOLITANISM 21 CATEGORICAL IMPERATIVES 22 THEATRE AND COSMOPOLITANISM 22 IDENTIFICATION 23 METAPHOR AND SYMBOL 24 THEATRICALITY AND UNITY 25 BEAUTY AND COMPLEXITY 26 CHAPTER 3 27 THE DRAMATURGY OF REALTV – EPIC AND COSMOPOLITAN DRAMATURGY FOR THE GLOBAL AGE 27 FACT AND FICTION IN REALTV PLAY TEXTS 27 EPIC DRAMATURGY 28 STRUCTURE 32 DEFAMILIARISATION THROUGH POETIC LANGUAGE 34 COSMOPOLITAN DRAMATURGY 35 EVAPORATION OF SINGULARITY 36 DE-TERRITORIALISM 36 CHAPTER 4 39 FORMS OF REPRESENTATION - BRECHTIAN TECHNIQUES STAGING WORK FOR YOUNG AUDIENCES 39 WAR CRIMES - THEMES AND ISSUES 39 DIRECTORIAL STYLE 40 CROSS-RACIAL CASTING 41 CULTURAL SENSITIVITY 42 SUBVERTING PATRIARCHAL CONSTRUCTS 46 ALIENATION EFFECT, CONTRADICTION AND CROSS GENDER ROLE PLAY 47 QUEER REPRESENTATION 48 HIP-HOP 49 DESIGN 51 SOUND DESIGN 53 MASH-UP 54 CHAPTER 5 57 AUDIENCE FEEDBACK 57 DIRECTOR’S RESPONSE 58 CHAPTER 6 65 CONCLUSION 65 BIBLIOGRAPHY 67 ii Abstract One of key struggles of the globalised twenty-first century is against the disempowerment of the individual imagination. -

SPJ-Issue-2019-03

2019 ♦ 3 Auslender Bufnilă Crow Dibble Guha Kelly Kriz Lemaire Martín Rodríguez Mina Silva Yoakeim sciphijournal.org ♦ [email protected] 1 CREW CONTENTS Co-editors: 3 Editorial Ádám Gerencsér Mariano Martín Rodríguez 4 « Asymptotic Convergence» Communications: Gina Adela Ding Ramez Yoakeim Webmaster: Ismael Osorio Martín 6 « The Greatest Good to God» Contact: Andy Dibble [email protected] 9 « Byzantine Theology in Alternate History: not such a serious matter?» Pascal Lemaire 16 « Winged Spirit» Luís Filipe Silva Translation and introductory note by Rex Nielson 19 « Peripheric Synthesized» Ava Kelly 22 « Relative Perception» Brishti Guha 26 « New Worlds, Old Worlds» Mina 30 « In Vivo Genome-editing Rescues Damnatio Memoriae in a Mouse Model of Titor Syndrome» Andrea Kriz 34 « A Note on Romanian Science Fiction Literature from Past to Present» Mariano Martín Rodríguez 39 « The Arms of the Gods » Ovidiu Bufnilă Introductory note and translation by Cătălin Badea-Gheracostea 42 « Hyrenas» E.N. Auslender 46 « A Reflection on the Achievement of Gene Wolfe, with Gregorian Chant Echoing Offstage» Blackstone Crow 2 Editorial At the time of writing, Ádám of the SPJ editorial team this heterodox society that oftentimes intimates a is on pilgrimage to the Holy Land. Yet the primary Mediterranean re-imagining of Blade Runner, where impressions his sojourn inspires belong not in the college girls in army uniform carrying assault rifles realm of theology, but world building. (Admittedly, mingle with Haredim and rainbow warriors at the two are related.) retrofuturist malls, has nonetheless managed to forge a sense of identity and purpose. To an avid reader of the fantastic, even a cursory intercourse with the State of Israel reveals it as a prime It even has its own hermetic SF scene in Hebrew, example of applied utopian SF.