Processes, Information, and Accounting Gaps in the Regulation of Argentina’S Private Railways

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acta Acuerdo Para La Operacion De Los Servicios Interurbanos De Pasajeros

ACTA ACUERDO PARA LA OPERACION DE LOS SERVICIOS INTERURBANOS DE PASAJEROS CORREDOR CIUDAD DE BUENOS AIRES – CIUDAD DE CORDOBA Página 1 de 13 Entre la SECRETARIA DE TRANSPORTE del MINISTERIO DE PLANIFICACION FEDERAL, INVERSION PUBLICA Y SERVICIOS, representada en este acto por el Sr. Secretario de Transporte Ingeniero RICARDO JAIME, con domicilio en Hipólito Irigoyen 250 de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires (en adelante, el CONCEDENTE) por una parte; y por la otra, NUEVO CENTRAL ARGENTINO S.A. a través de FERROCENTRAL S.A. (e.f.), (en adelante, el CONCESIONARIO) representada por el Sr. HECTOR SALVADOR CIMO con domicilio en Av. Ramos Mejía 1430 1º Piso, Ciudad de Buenos Aires; integrada por las empresas FERROVIAS S.A.C. representada por el Sr. OSVALDO ROMAN ALDAO con domicilio en Ramos Mejía 1430, 4º Piso, Ciudad de Buenos Aires y NUEVO CENTRAL ARGENTINO S.A. representada en este acto por el Lic. MIGUEL ANGEL ACEVEDO con domicilio en Avda. Alem 986 10º piso, Ciudad de Buenos Aires y conjuntamente denominados todos ellos como las PARTES; CONSIDERANDO Que por Decretos N° 532 de fecha 27 de marzo de 1992 y N° 1168 de fecha 10 de julio de 1992 se interesó a los gobiernos provinciales en cuyos territorios se asentaban ramales ferroviarios en actividad o clausurados, incluidos en la nómina incorporada al citado Decreto N° 532/92 como Anexo I, para que explotaran la concesión de los mismos en los términos del Artículo 4° del Decreto N° 666 del 1° de septiembre de 1989. Que por los Convenios firmados el 21 de octubre de 1992 y el 9 de septiembre de 1993 entre el ESTADO NACIONAL, la PROVINCIA DE CORDOBA, FERROCARRILES ARGENTINOS y FERROCARRILES METROPOLITANOS S.A. -

Ministerio De Economía Y Finanzas Públicas Secretaría De Política Económica Subsecretaría De Coordinación Económica Dirección Nacional De Inversión Pública

MINISTERIO DE ECONOMÍA Y FINANZAS PÚBLICAS SECRETARÍA DE POLÍTICA ECONÓMICA SUBSECRETARÍA DE COORDINACIÓN ECONÓMICA DIRECCIÓN NACIONAL DE INVERSIÓN PÚBLICA SISTEMA DE TRANSPORTE FERROVIARIO: ESCENARIOS FUTUROS Y SU IMPACTO EN LA ECONOMÍA PRÉSTAMO BID 1896/OC-AR PROYECTO DINAPREI 1.EE.517 Juan Alberto ROCCATAGLIATA Juan BASADONNA Javier MARTÍNEZ HERES Pablo GARCÍA Santiago BLANCO INFORME FINAL TOMO I BUENOS AIRES Índice TOMO I RESUMEN EJECUTIVO 3 INTRODUCCIÓN 29 A. EL SISTEMA DE TRANSPORTE, UNA VISIÓN DE CONJUNTO 36 B. ESTADO DE SITUACIÓN ACTUAL, DEL CUADRO SITUACIONAL ACTUAL AL REDISEÑO DEL SISTEMA 65 C. EXPLICACIÓN DEL PLAN “SISTEMA FERROVIARIO ARGENTINO 2025” IDENTIFICACIÓN DE LOS POSIBLES ESCENARIOS FUTUROS DESDE UNA VISIÓN ESTRATÉGICA 69 D. DIRECTRICES ESTRATÉGICAS PARA EL MODELO FERROVIARIO ARGENTINO, HORIZONTE 2025 81 E. COMPONENTES DEL SISTEMA A SER PENSADO Y DISEÑADO 162 1. Contexto institucional para la reorganización y gestión del sistema ferroviario. 2. Rediseño y reconstrucción de las infraestructuras ferroviarias de la red de interés federal. 3. Sistema de transporte de cargas. Intermodalidad y logística. 4. Sistema interurbano de pasajeros de largo recorrido. 5. Sistema de transporte metropolitano de cercanías de la metápolis de Buenos Aires y en otras aglomeraciones del país. 6. Desarrollo industrial ferroviario de apoyo al plan. F. ESCENARIOS PROPUESTOS 173 Programas, proyectos y actuaciones priorizados. TOMO II G. IDENTIFICACIÓN DE LOS PROGRAMAS, PROYECTOS Y ACTUACIONES 193 Análisis de demanda y proyección de la oferta TOMO III H. EVALUACIÓN AMBIENTAL ESTRATÉGICA 351 I. IMPACTO EN EL NIVEL DE EMPLEO, PBI Y RETORNO FISCAL 463 2 RESUMEN EJECUTIVO 3 DIAGNÓSTICO Del cuadro situacional actual al rediseño del sistema No es intención del presente trabajo realizar un diagnóstico clásico de la situación actual del sistema ferroviario argentino. -

La Privatización Y Desguace Del Sistema Ferroviario Argentino Durante El Modelo De Acumulación Neoliberal

La privatización y desguace del sistema ferroviario argentino durante el modelo de acumulación neoliberal Nombre completo autor: Franco Alejandro Pagano Pertenencia institucional: Universidad Nacional de Cuyo Correo electrónico: [email protected] Mesa temática: Nº 6: Sociología Económica: las correlaciones de fuerzas en los cambios de los patrones acumulación del capital. Disciplinas: Ciencia política y administración pública. Sociología. Palabras claves: Privatización, neoliberalismo, ferrocarriles, transporte, modelo de acumulación, éxodo rural. Resumen: En Argentina, a partir de 1976, el sistema industrial y productivo del país sufrió fuertes transformaciones a partir de la implementación del paradigma neoliberal imperante a nivel internacional. Este cambio estructural, implementado de forma gradual, alteró también -conjuntamente a las relaciones de producción- la dinámica social, laboral, educacional e institucional del país, imprimiendo una lógica capitalista a todo el accionar humano. Como parte de ello se dio en este periodo el proceso de concesiones, privatización y cierre de la mayoría de los ramales ferroviarios que poseía el país, modificando hasta nuestros días la concepción de transporte y perjudicando seriamente al colectivo nacional. De las graves consecuencias que esto produjo trata este trabajo. Ponencia: 1.0 Golpe de Estado de 1976. Etapa militar del neoliberalismo El golpe cívico-militar del 24 de marzo de 1976 podría reconocerse como la partida de nacimiento del neoliberalismo en la Argentina, modelo económico que se implementará por medio la fuerza -buscando el disciplinamiento social- con terror y violencia. Se iniciaba así un nuevo modelo económico basado en la acumulación 1 rentística y financiera, la apertura irrestricta, el endeudamiento externo y el disciplinamiento social” (Rapoport, 2010: 287-288) Como ya sabemos este nuevo modelo de acumulación comprende un conjunto de ideas políticas y económicas retomadas del liberalismo clásico: el ya famoso laissez faire, laissez passer. -

Redalyc.ALTA VELOCIDAD FERROVIARIA: LA EXPERIENCIA

Revista Transporte y Territorio E-ISSN: 1852-7175 [email protected] Universidad de Buenos Aires Argentina Schweitzer, Mariana ALTA VELOCIDAD FERROVIARIA: LA EXPERIENCIA EN ESPAÑA, FRANCIA Y ALEMANIA Y LOS PROYECTOS PARA ARGENTINA Revista Transporte y Territorio, núm. 5, 2011, pp. 89-120 Universidad de Buenos Aires Buenos Aires, Argentina Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=333027083006 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto ARTÍCULO Mariana Schweitzer ALTA VELOCIDAD FERROVIARIA: LA EXPERIENCIA EN ESPAÑA, FRANCIA Y ALEMANIA Y LOS PROYECTOS PARA ARGENTINA Revista Transporte y Territorio Nº 5, Universidad de Buenos Aires, 2011. Revista Transporte y Territorio ISSN 1852-7175 www.rtt.filo.uba.ar Programa Transporte y Territorio Instituto de Geografía Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Universidad de Buenos Aires Cómo citar este artículo: SCHWEITZER, Mariana. 2011. Alta velocidad ferroviaria: la experiencia en España, Francia y Alemania y los proyectos para argentina. Revista Transporte y Territorio Nº 5, Universidad de Buenos Aires. pp. 89-120. <www.rtt.filo.uba.ar/RTT00506089.pdf> Recibido: 31 de marzo de 2011 Aceptado: 16 de mayo de 2011 Alta velocidad ferroviaria: la experiencia en España, Francia y Alemania y los proyectos para Argentina Mariana Schweitzer Alta velocidad ferroviaria: la experiencia en España, Francia y Alemania y los proyectos para Argentina. Mariana Schweitzer* RESUMEN En la Argentina, que ha visto la desaparición de la gran mayoría del transporte interurbano de pasajeros, la privatización de ramales para el trasporte de cargas y de los servicios del área metropolitana de Buenos Aires, se introducen proyectos de alta velocidad ferroviaria. -

Privatesector

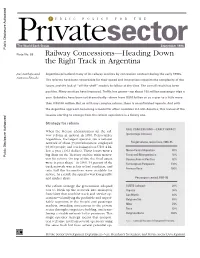

P UBLIC POLICYsector FOR THE TheP World Bankrivate Group September 1996 Public Disclosure Authorized Note No. 88 Railway Concessions—Heading Down the Right Track in Argentina José Carbajo and Argentina privatized many of its railway services by concession contract during the early 1990s. Antonio Estache The reforms have been remarkable for their speed and innovation—despite the complexity of the issues and the lack of “off-the-shelf” models to follow at the time. The overall result has been positive. Many services have improved. Traffic has grown—up about 180 million passenger trips a year. Subsidies have been cut dramatically—down from US$2 billion or so a year to a little more than US$100 million. But as with any complex reform, there is an unfinished agenda. And with Public Disclosure Authorized the Argentine approach becoming a model for other countries in Latin America, this review of the lessons starting to emerge from the reform experience is a timely one. Strategy for reform RAIL CONCESSIONS—EARLY IMPACT When the Menem administration set the rail- way reform in motion in 1990, Ferrocarriles (percentage increase) Argentinos, the largest operator, ran a national network of about 35,000 kilometers, employed Freight volume, major lines, 1990–95 92,000 people, and was losing about US$1.4 bil- lion a year (1992 dollars). These losses were a Nuevo Central Argentino 40% big drain on the Treasury and the main motiva- Ferrocarril Mesopotámico 50% Public Disclosure Authorized tion for reform. On top of this, the fixed assets Buenos Aires al Pacífico 92% were in poor shape—in 1990, 54 percent of the Ferroexpreso Pampeano 130% track network was in fair or bad condition, and Ferrosur Roca 160% only half the locomotives were available for service. -

1 CAMARA DE DIPUTADOS DE BUENOS AIRES Período 142º

1 CAMARA DE DIPUTADOS DE BUENOS AIRES Período 142º 50 ASUNTOS ENTRADOS Entrados en la sesión del 25 de febrero de 2015 PROYECTOS DE LEY. 3.080 (D/3.978/14-15) Señora diputada Amendolara, modificación de artículos y modificatorias de la ley 5.827, orgánica del Poder Judicial, creación de tribunales de Trabajo con asiento en la ciudad de La Plata. PROYECTO DE LEY El Senado y Cámara de Diputados, etc. Art. 1º - Créase tres (3) Tribunales de Trabajo con asiento en la ciudad de La Plata. Art. 2º - Sustituyese el artículo 24 de la ley 5.827 -Orgánica del Poder Judicial- texto ordenado por decreto 3.702/92 y modificatorias por el siguiente: Art. 24 - Los Tribunales de Trabajo tendrán asiento: - Departamento Judicial Avellaneda-Lanús: cuatro (4) en la ciu- dad de Avellaneda y cuatro (4) en la ciudad de Lanús. - Departamento Judicial Azul: uno (1) en la ciudad de Azul, uno (1) en la ciudad de Olavarría y uno (1) en la ciudad de Tandil. - Departamento Judicial Bahía Blanca: dos (2) en la ciudad de Bahía Blanca y uno (1) en la ciudad de Tres Arroyos. - Departamento Judicial Dolores: dos (2) en la ciudad de Dolores, uno (1) en la ciudad de Mar del Tuyú. - Departamento Judicial Junín: uno (1) en la ciudad de Junín y uno (1) en la ciudad de Chacabuco. - Departamento Judicial La Plata: ocho (8) en la ciudad de La Plata. 2 - Departamento Judicial La Matanza: seis (6) en la ciudad de San Justo. - Departamento Judicial Lomas de Zamora: seis (6) en la ciudad de Lomas de Zamora. -

Redalyc.Argentina, ¿País Sin Ferrocarril? La Dimensión Territorial

Revista Transporte y Territorio E-ISSN: 1852-7175 [email protected] Universidad de Buenos Aires Argentina Benedetti, Alejandro Argentina, ¿país sin ferrocarril? La dimensión territorial del proceso de reestructuración del servicio ferroviario (1957, 1980 y 1998) Revista Transporte y Territorio, núm. 15, 2016, pp. 68-85 Universidad de Buenos Aires Buenos Aires, Argentina Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=333047931005 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Revista Transporte y Territorio /15 (2016) ISSN 1852-7175 68 [68-85] Argentina, ¿país sin ferrocarril? La dimensión territorial del proceso de reestructuración del servicio ferroviario (1957, 1980 y 1998)* Alejandro Benedetti " CONICET/Instituto de Geografía, Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina Resumen Desde inicios de la década de 1990 en Argentina se han implementado un conjunto de políticas tendientes a la liberalización y desregulación de la economía y a la privatización de activos del Estado. Esto incluyó la concesión de servicios ferroviarios, cuyo proceso comenzó en 1991. La privatización del ferrocarril suscitó cambios estructurales tanto en las pautas de organización del servicio como en las dimensiones de la infraestructura habilitada. Si bien este proceso de transformación tuvo gran repercusión en su momento, es notable la escasez de información existente sobre su magnitud. Esta investigación se propuso construir una serie de indicadores a través de los cuales se podría medir las transformaciones territoriales ocurridas tras la concesión del servicio a las empresas particulares y a los estados provinciales. -

Suroeste De La Provincia De Buenos Aires

Cnel. Suárez Gral. La Madrid Laprida Saavedra Cnel. Pringles Puan Tornquist Cnel. Dorrego Tres Arroyos Bahía Blanca Cnel. Rosales Villarino Monte Hermoso Patagones Suroeste de la Provincia de Buenos Aires 1 Industria Manufacturera. Año 2007 OBSERVATORIO PYME REGIONAL Suroeste de la Provincia de Buenos Aires Instituciones promotoras: Università di Bologna, Representación en Buenos Aires Consorcio del Parque Industrial de Bahía Blanca Fundación Observatorio Pyme Municipalidad de Bahía Blanca Dirección Provincial de Estadística, Municipalidad de Coronel de Marina Leonardo Ministerio de Economía de la Prov. de Buenos Aires Rosales Universidad Tecnológica Nacional, Facultad Regional Bahía Blanca Industria manufacturera año 2007. Observatorio Pyme Regional Suroeste de la Provincia de Buenos Aires / Vicente Donato ... [et.al.] ; dirigido por Vicente Donato. - 1a ed. - Buenos Aires: Fund. Ob- servatorio Pyme, Universidad Tecnológica Nacional, Bononiae Libris, 2008. 180 p. ; 30x21 cm. ISBN 978-987-24223-4-9 1. Pequeña y Mediana Empresa. I. Donato, Vicente II. Donato, Vicente, dir. CDD 338.47 Fecha de catalogación: 17/09/2008 2 Equipo de trabajo Proyecto Observatorios PyME Regionales Dirección: Vicente N. Donato, Università di Bologna Coordinación general: Christian M. Haedo, Università di Bologna - Representación en Buenos Aires Coordinación institucional: Silvia Acosta, Fundación Observatorio PyME Università di Bologna - Representación en Buenos Aires, Fundación Observatorio PyME Centro de Investigaciones Metodología y estadística: Metodología y estadística: Pablo Rey Andrés Farall Investigación: Directorio de locales industriales: Ignacio Bruera Cecilia Queirolo Florencia Barletta Comunicación y prensa: Ivonne Solares Asistencia General: Vanesa Arena Dirección Provincial de Estadística, Ministerio de Economía Observatorio PyME Regional Suroeste de la Provincia de la Provincia de Buenos Aires de Buenos Aires Director: Hugo Fernández Acevedo Coordinación: María Susana Porris, U ni v ersidad T ecnológica N a cional. -

Revista Del Centro De Estudios De Sociología Del Trabajo Nº6/2014 Paradojas Del Sistema Ferroviario Argentino (Pp

Paradojas del sistema ferroviario argentino: reflexiones en torno a la confiabilidad y la vulnerabilidad en una línea metropolitana Natalia L. Gonzalez1 Resumen * El riesgo y la seguridad del transporte ferroviario de pasajeros en la Argentina regresaron al centro de la escena a partir de los accidentes ocurridos desde 2011, evidenciando el deterioro de la infraestructura ferroviaria y material rodante, las fallas en la gestión y en el funcionamiento de las líneas. Se analizan los elementos asociados a la vulnerabilidad y confiabilidad del sistema ferroviario focalizando el caso de la línea Belgrano Sur. Se señalan las representaciones sociales sobre el riesgo que los trabajadores ferroviarios construyen de manera contradictoria con las manifestadas por la opinión pública. Así, el factor humano considerado por el mainstream del análisis de accidentes como una fuente indiscutible de la vulnerabilidad, se presenta como una de las fuentes de la confiabilidad. Palabras clave: gestión del riesgo, confiabilidad, prácticas de conductores de locomotoras, línea férrea metropolitana, Belgrano Sur, vulnerabilidad, representaciones sociales. Paradoxes of the Argentine Railway System: Reflexions regarding Reliability and Vulnerability of one City Route Abstract The debate about risk and safety of train passengers reappeard in Argentina after 2011 as a consequence of the major accidents that occurred since then. These accidents revealed both the deteriorated condition of roads and tractive equipment, and failures in management and Fecha de recepción : 23/12/2013 – Fecha de aceptación: 25/02/2014 1 Investigadora-docente, Universidad Nacional de General Sarmiento. Argentina. Email [email protected] * Agradezco los pertinentes comentarios de los evaluadores de este trabajo. 112 Natalia Gonzalez operation of the lines. -

IF-2019-12952289-APN-SSP#MHA Página 1 De 3

ANEXO I PRESUPUESTO 2019 DESARROLLO DEL CAPITAL HUMANO FERROVIARIO SOCIEDAD ANÓNIMA CON PARTICIPACIÓN ESTATAL MAYORITARIA S.A.P.E.M. PLAN DE ACCIÓN OBJETIVOS Descripción del entorno operacional y situación actual: Mediante la resolución 533 del 11 de junio de 2013 del entonces Ministerio del Interior y Transporte se dispuso el cese de la Intervención Administrativa de la empresa, dispuesta a través de la resolución conjunta 252 del ex Ministerio de Infraestructura y Vivienda y 736 del entonces Ministerio de Economía del 30 de agosto de 2000. En cumplimiento de lo establecido, mediante la disposición 538 del 14 de junio de 2013 de la entonces Subsecretaría de Transporte Ferroviario dependiente de la ex Secretaría de Transporte del Ministerio citado en primer término, se llamó a Asamblea de Accionistas a los fines de designar miembros del Directorio, integrantes de la Comisión Fiscalizadora, incluir a la Empresa en el Régimen de la Sección VI de la ley 19.550 y recomendar al Directorio la modificación de la denominación por Administradora de Recursos Humanos Ferroviarios Sociedad Anónima con Participación Estatal Mayoritaria y la modificación del Estatuto en cuanto al objeto social, que es principalmente la administración general, evaluación, formación y capacitación de los Recursos Humanos Ferroviarios del Estado Nacional y la guarda, custodia y archivo de la documentación correspondiente a la ex Ferrocarriles Argentinos. A través del decreto 428 del 17 de marzo de 2015 se dispuso la fusión de la Administradora de Recursos Humanos Ferroviarios Sociedad Anónima con Participación Estatal Mayoritaria en la Operadora Ferroviaria Sociedad del Estado, en los términos previstos en el artículo 82 de la ley 19.550. -

Master Document Template

Copyright by Katherine Schlosser Bersch 2015 The Dissertation Committee for Katherine Schlosser Bersch Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: When Democracies Deliver Governance Reform in Argentina and Brazil Committee: Wendy Hunter, Co-Supervisor Kurt Weyland, Co-Supervisor Daniel Brinks Bryan Jones Jennifer Bussell When Democracies Deliver Governance Reform in Argentina and Brazil by Katherine Schlosser Bersch, B.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2015 Acknowledgements Many individuals and institutions contributed to this project. I am most grateful for the advice and dedication of Wendy Hunter and Kurt Weyland, my dissertation co- supervisors. I would also like to thank my committee members: Daniel Brinks, Bryan Jones, and Jennifer Bussell. I am particularly indebted to numerous individuals in Brazil and Argentina, especially all of those I interviewed. The technocrats, government officials, politicians, auditors, entrepreneurs, lobbyists, journalists, scholars, practitioners, and experts who gave their time and expertise to this project are too many to name. I am especially grateful to Felix Lopez, Sérgio Praça (in Brazil), and Natalia Volosin (in Argentina) for their generous help and advice. Several organizations provided financial resources and deserve special mention. Pre-dissertation research trips to Argentina and Brazil were supported by a Lozano Long Summer Research Grant and a Tinker Summer Field Research Grant from the University of Texas at Austin. A Boren Fellowship from the National Security Education Program funded my research in Brazil and a grant from the University of Texas Graduate School provided funding for research in Argentina. -

Estudios Sobre Planificación Sectorial Y Regional

ISSN 2591-3654 ESTUDIOS SOBRE PLANIFICACIÓN SECTORIAL Y REGIONAL DICIEMBRE 2017 Año 2 N° 4 Logística. Temas de Agenda Secretaría de Política Económica Estudios sobre Planificación Sectorial y Regional ESTUDIOS SOBRE PLANIFICACIÓN SECTORIAL Y REGIONAL DICIEMBRE 2017 INDICE Introducción…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…………… 4 Sistema ferroviario de cargas. Caracterización y desafíos de la política pública ……………………..……………… 5 Bitrenes. Su implementación en Argentina ….......................................................................................... 36 Costos logísticos. La incidencia del flete interno en las operaciones de exportación…………………………….. 50 Esta serie de informes tiene por objeto realizar una descripción analítica y específica sobre temáticas de particular relevancia para la planificación del desarrollo productivo sectorial y regional del país. Se consideran temáticas transversales como: empleo, innovación, educación, tecnología, desarrollo regional, inserción internacional, entre otros aspectos de relevancia. Publicación propiedad del Ministerio de Hacienda de la Nación. Director Dr. Mariano Tappatá. Registro DNDA en trámite. Hipólito Yrigoyen 250 Piso 8° (C1086 AAB) Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires – República Argentina. Tel: (54 11) 4349-5945 y 5918. Correo electrónico: [email protected] URL: http://www.minhacienda.gob.ar SUBSECRETARIA DE PROGRAMACIÓN MICROECONÓMICA Dirección Nacional de Planificación Sectorial - Dirección Nacional de Planificación Regional ESTUDIOS SOBRE PLANIFICACIÓN SECTORIAL Y REGIONAL