Melodramatic Imagination in Ritwik Ghatak's Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Alberta

University of Alberta The Refugee Woman: Partition of Bengal, Women, and the Everyday of the Nation by Paulomi Chakraborty A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English and Film Studies ©Paulomi Chakraborty Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-55963-5 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-55963-5 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

Sanitation and Health at West Bengal Refugee Camps in the 1950S

Vidyasagar University Journal of History, Volume III, 2014-20156, Pages: 82-94 ISSN 2321-0834 Sanitation and Health at West Bengal Refugee Camps in the 1950s Swati Sengupta Chatterjee Abstract: East Pakistan refugees arrived at West Bengal in different phases and were grouped into two categories: the ‘old’ arriving during 1946-1958, and the ‘new’ during 1964-1971. The West Bengal Government took the responsibility of rehabilitation of the ‘old’ refugees, but not the ‘new’ ones; eventually it did, but only on the condition that they re-settle outside the state. But even the old refugees staying at the camps of West Bengal received atrocious treatment. This paper focuses on sanitary and health conditions at the old refugee camps in the 1950’s. Although the Government assumed a policy of relief, surprisingly, hardly anything was provided to the refugees staying at the camps. Also, neither proper medical aid nor proper sanitary arrangements were provided to them. Lack of proper sanitary conditions in the camps led to the spread of infectious diseases that took epidemic proportions. This was in sharp contrast to the northern Indian camps where medical aid was provided systematically. Key words: Partition, Health and Sanitation, Refugee Camps, Diseases, Government Policies. The condition of two interrelated aspects of West Bengal camp refugee life in the 1950s – sanitation and health – was deplorable and hardly improved much over time. Undoubtedly, this reflected the approach of the West Bengal Government and its policy towards refugees; indeed, health aid received by the camp refugees of north India in 1948 and those in West Bengal in the 1950s reveal a glaring contrast. -

Nandan Gupta. `Prak-Bibar` Parbe Samaresh Basu. Nimai Bandyopadhyay

BOOK DESCRIPTION AUTHOR " Contemporary India ". Nandan Gupta. `Prak-Bibar` Parbe Samaresh Basu. Nimai Bandyopadhyay. 100 Great Lives. John Cannong. 100 Most important Indians Today. Sterling Special. 100 Most Important Indians Today. Sterling Special. 1787 The Grand Convention. Clinton Rossiter. 1952 Act of Provident Fund as Amended on 16th November 1995. Government of India. 1993 Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action. Indian Institute of Human Rights. 19e May ebong Assame Bangaliar Ostiter Sonkot. Bijit kumar Bhattacharjee. 19-er Basha Sohidera. Dilip kanti Laskar. 20 Tales From Shakespeare. Charles & Mary Lamb. 25 ways to Motivate People. Steve Chandler and Scott Richardson. 42-er Bharat Chara Andolane Srihatta-Cacharer abodan. Debashish Roy. 71 Judhe Pakisthan, Bharat O Bangaladesh. Deb Dullal Bangopadhyay. A Book of Education for Beginners. Bhatia and Bhatia. A River Sutra. Gita Mehta. A study of the philosophy of vivekananda. Tapash Shankar Dutta. A advaita concept of falsity-a critical study. Nirod Baron Chakravarty. A B C of Human Rights. Indian Institute of Human Rights. A Basic Grammar Of Moden Hindi. ----- A Book of English Essays. W E Williams. A Book of English Prose and Poetry. Macmillan India Ltd.. A book of English prose and poetry. Dutta & Bhattacharjee. A brief introduction to psychology. Clifford T Morgan. A bureaucrat`s diary. Prakash Krishen. A century of government and politics in North East India. V V Rao and Niru Hazarika. A Companion To Ethics. Peter Singer. A Companion to Indian Fiction in E nglish. Pier Paolo Piciucco. A Comparative Approach to American History. C Vann Woodward. A comparative study of Religion : A sufi and a Sanatani ( Ramakrishana). -

0X0a I Don't Know Gregor Weichbrodt FROHMANN

0x0a I Don’t Know Gregor Weichbrodt FROHMANN I Don’t Know Gregor Weichbrodt 0x0a Contents I Don’t Know .................................................................4 About This Book .......................................................353 Imprint ........................................................................354 I Don’t Know I’m not well-versed in Literature. Sensibility – what is that? What in God’s name is An Afterword? I haven’t the faintest idea. And concerning Book design, I am fully ignorant. What is ‘A Slipcase’ supposed to mean again, and what the heck is Boriswood? The Canons of page construction – I don’t know what that is. I haven’t got a clue. How am I supposed to make sense of Traditional Chinese bookbinding, and what the hell is an Initial? Containers are a mystery to me. And what about A Post box, and what on earth is The Hollow Nickel Case? An Ammunition box – dunno. Couldn’t tell you. I’m not well-versed in Postal systems. And I don’t know what Bulk mail is or what is supposed to be special about A Catcher pouch. I don’t know what people mean by ‘Bags’. What’s the deal with The Arhuaca mochila, and what is the mystery about A Bin bag? Am I supposed to be familiar with A Carpet bag? How should I know? Cradleboard? Come again? Never heard of it. I have no idea. A Changing bag – never heard of it. I’ve never heard of Carriages. A Dogcart – what does that mean? A Ralli car? Doesn’t ring a bell. I have absolutely no idea. And what the hell is Tandem, and what is the deal with the Mail coach? 4 I don’t know the first thing about Postal system of the United Kingdom. -

Deepa Mehta's Elemental Trilogy and the Depiction of Indian Culture In

Deepa Mehta’s Elemental Trilogy and the Depiction of Indian Culture in Select Filmic Adaptations A Thesis Submitted to For the award of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH Submitted by: Supervised by: Ishfaq Ahmad Tramboo Dr. Nipun Chaudhary Reg. No. 11512772 Assistant Professor Department of English LOVELY FACULTY OF BUSINESS AND ARTS LOVELY PROFESSIONAL UNIVERSITY PHAGWARA-144411 (PUNJAB) 2019 Declaration I hereby declare that the thesis entitles Deepa Mehta’s Elemental Trilogy and The Depiction of Indian Culture in Select Filmic Adaptations submitted for the partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of degree of Doctor of Philosophy is entirely my original work. All the ideas and references are duly acknowledged. It does not contain any other work for the award of any other degree or diploma at any university or institution. I hereby confirm that I have carefully checked the final version of printed and softcopy of the thesis for the completeness and for the incorporation of all the valuable suggestions of Doctoral Board of the University. I hereby submit the final version of the printed copy of my thesis as per the guidelines and the exact same content in CD as a separate PDF file to be uploaded in Shodhganga. Place: Phagwara Ishfaq Ahmad Tramboo Date: 31 July 2019 (11512772) ii Certificate By Advisor I hereby affirm as under that: 1) The thesis presented by Ishfaq Ahmad Tramboo entitled “Deepa Mehta’s Elemental Trilogy and The Depiction of Indian Culture in Select Filmic Adaptations” is worthy of consideration for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. -

Paulomi Chakraborty

University of Alberta The Refugee Woman: Partition of Bengal, Women, and the Everyday of the Nation by Paulomi Chakraborty A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English and Film Studies ©Paulomi Chakraborty Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Examining Committee Stephen Slemon, English and Film Studies Heather Zwicker, English and Film Studies Onookome Okome, English and Film Studies Sourayan Mookerjea, Sociology Rajeswari Sunder Rajan, English, New York University I dedicate this dissertation to the memory of Rani Chattopadhyay and Birendra Chattopadhyay, my grandparents Abstract In this dissertation I analyze the figure of the East-Bengali refugee woman in Indian literature on the Partition of Bengal of 1947. I read the figure as one who makes visible, and thus opens up for critique, the conditions that constitute the category ‘women’ in the discursive terrain of post-Partition/post-Independence India. -

Re-E-Tender for PROCUREMENT of BENGALI BOOKS (PHASE 1)FOR KOLKATA POLICE LIMELIGHT LIBRARY

Notice Inviting e-Tender P a g e ||| 111 NIT [ NOTICE INVITING e-TENDER ] No. : WBKP/CP/NIT 271 / BENGALI BOOKS (PHASE 1) FOR LIBRARY /TEN Dated : 25/ 01/201 9 Re-e-Tender FOR PROCUREMENT OF BENGALI BOOKS (PHASE 1)FOR KOLKATA POLICE LIMELIGHT LIBRARY KOLKATA POLICE DIRECTORATE Tender Section, 18, Lalbazar Street, Kolkata – 700 001. Ph. : (033) 2250 5275 / (033) 2250-5048 e-Mail : [email protected] 222 ||| P a g e Notice Inviting e-Tender TABLE OF CONTENTS NOTICE INVITING Re-e-TENDER ............................................................................................................................. 3 I. PRE-BID QUALIFICATIONS ............................................................................................ 4 1. Company Registration : ...................................................................................................................... 4 2. Undertaking Regarding Blacklisting : ................................................................................................. 4 3. Partnership Firm (if applicable) :........................................................................................................ 4 4. Annual Turnover : ............................................................................................................................... 4 5. Work Experience : ............................................................................................................................... 4 6. PAN No. : ............................................................................................................................................. -

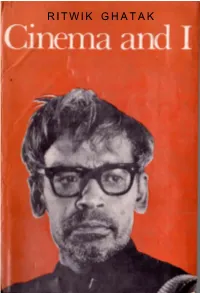

Ritwik Ghatak

RITWIK GHATAK Ritwik Ghatak Cinema and I First Published 17th January 1987 Published by Ritwik Memorial Trust With support from Federation of Film Societies of India © Ritwik Memorial Trust All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented. Including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission In writing from the publisher. Cover designed by Satyajit Ray Cover photograph from Jukti Takko ArGappo Photo type setting by Pratikshan Publications Pvt. Ltd Reproduced by Quali Photo Process Pvt. Ltd Printed at A O P (India) Pvt. Ltd Distributed exclusively in India by Post Box No. 12333 15 Bankim Chatterjee Street Calcutta-700 073 Branches: Allahabad. Bombay, New Delhi, Bangalore. Madras, Hyderabad. RITWIK MEMORIAL TRUST 1/10 Prince Golam Mohd Road Calcutta-700 026 The present volume is the first in the series of publications of Ritwik Ghatak's works entitled Ritwik Rachana Samagra. Contents Publisher's note 9 Acknowledgements 10 Foreword by Satyajit Ray 11 Film and 1 13 My Coming into films 19 Bengali Cinema: Literary Influence 21 What Ails Indian Film-Making 26 Some Thoughts on Ajantrik 31 Experimental Cinema 34 Sound in Film 38 Music in Indian Cinema and the Epic Approach 41 Experiment in Cinema and I 44 Documentary: the Most Exciting form of Cinema 46 Cinema and the Subjective Factor 60 Film-Making 65 Interview (1) 68 Interview (2) 77 Nazarin 81 A book review: Theory of Film 84 An Attitude to life and an Attitude to Art Appendix About Oraons (Chotonagpur) 91 Check-list 105 Publisher's Note Ritwik Ghatak's creative exercises spanned through many a medium of expression—poetry, short story, play, film. -

Popular Bengali Novel

ISSN: 2456–5474 RNI No.UPBIL/2016/68367 Vol.-5* Issue-11* December- 2020 Popular Bengali Novel: Theoretical Aspects and Relevance Paper Submission: 15/12/2020, Date of Acceptance: 26/12/2020, Date of Publication: 27/12/2020 Abstract About popularity, we cherish some primary misconceptions related to market. Like the word ‘commercial’, there is another current word ‘cheap popularity’, when someone purchases something with self- earned money, it reflects the difference of taste, mentality and environment, depicting a similarity within that group. Thus popularity is neither very easy nor inevitably cheap. Books, especially ‘novels’, being the object of such popularity, invites discussion. Qualitative difference between popular and serious literature is reflected in the thought of Bankimchandra, along with the socio- economic condition related to this. From the ‘Popular Literature of Bengal’ (1870) to ‘Battala Sahitya’, popularity gained weight. Our discussion aimed at formulating a generic idea of ‘popular novel’ from a ‘popular literature’ in the twentieth century Bengali literature; in the next phase the publication of the magazine ‘Desh’ (20th November, 1933) with commercial strategy. There, the assimilation of intellectualism and publication – generic evolution of popular novels and different theoretical schools will be discussed. Keywords: Popular Culture, Popular Literature, Pulp Fiction, Dime Novel, Market, Publication, Culture Industry, Best Seller, People Introduction "I used to write but entertaining people is not the religion of my pen, so people have a greater share of the ink in the colors that they always have. There are a lot of rumors about me; eventually, words are not beneficial, nor even pleasant." Rabindranath wrote this at the beginning of his short story Indrani Rooj 'Bostami'. -

A Study of Refugees, Resettlement and Rehabilitation in North Bengal with Special Reference to Women (1947-79)

In Quest of a New Destination: A study of Refugees, Resettlement and Rehabilitation in North Bengal with Special Reference to Women (1947-79) A Thesis Submitted To The North Bengal University For The Award of Doctor of Philosophy In Department of History Submitted by Madhuparna Mitra Guha Under the Supervision of Dr. Dahlia Bhattacharya Associate Professor Department of History North Bengal University Department of History North Bengal University December, 2018 i Abstract Amid construction and destruction of the outside world the tale of human civilization is embedded in history. The light and darkness of history carefully preserve the memory and oblivion that act silently to change the complexion of society, era and mid set. Partition of India was a tragic incident in the annals of human civilization that had caste such a long shadow. It remained as an apocalyptic event that reinforced violence and movement invoking political rupture, social catastrophe and also advocated nostalgia. The division of British India and subsequent creation of two antagonist countries was not just the splitting up of nations and their histories but also their very existence. The thesis emphasized on the fact that the partition of India purported only on religious lines creating two independent nations, viz. India and Pakistan. Both India and Pakistan had firm conviction that partition was the only way to get rid of existing turmoil. The prime objective of the paper is to highlight specially on the refugees who migrated to North Bengal. The displaced persons from East Pakistan had to traverse a long way riddled with hurdles to pay the cost of independence. -

CLOUD-CAPPED STAR, MEGHE DHAKA TARA 1960 Ritwik Ghatak

HUMANITIES INSTITUTE Stuart Blackburn, Ph.D. CLOUD-CAPPED STAR, MEGHE DHAKA TARA 1960 Ritwik Ghatak (Bengali language) OVERVIEW Cloud-Capped Star (Meghe Dhaka Tara) was adapted from a Bengali novel of the same name written by Shaktipada Rajguru. The film depicts the disintegration of a middle-class Bengali family who have been forced to leave their home in the east of Bengal during the Partition of 1948 and move to the west. A year earlier, when India became independent, Bengal was divided into East Pakistan (with a Muslim majority and part of Pakistan) and Bengal (with a Hindu majority and part of India). Many of the Hindus in the east uprooted their lives and moved west to Calcutta. The traumatic effects of that dislocation are dramatised in the life of Nita, a young student who sacrifices her happiness, and eventually her life, for the welfare of her family. Her struggle is only made bearable by her faith in two men whom she loves. Her brother, Shankar, redeems her faith at the end, but she is betrayal by her fiancé, Sanat. While the family fortunes do improve at the end, she has contracted tuberculosis and dies in a sanatorium, unfulfilled and alone. It is a compelling and heart-wrenching film that tells its story with attention to small details, such as food prices, and to grand themes, such as love and sacrifice. CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE Although this film, like other Indian melodramas, centres on the themes of self-sacrifice and thwarted desires, it rises far above sentimentality by the quiet unfolding of the tragedy, the superb acting and the noir-ish cinematography. -

E-Tender P a G E ||| 111

Notice Inviting e-Tender P a g e ||| 111 NIT [ NOTICE INVITING e-TENDER ] No. : WBKP/CP/NIT - 175 / BENGALI BOOKS FOR LIBRARY /TEN Dated : 24 / 09 /201 8 e-Tender FOR PROCUREMENT OF BENGALI BOOKS FOR KOLKATA POLICE LIMELIGHT LIBRARY KOLKATA POLICE DIRECTORATE Tender Section, 18, Lalbazar Street, Kolkata – 700 001. Ph. : (033) 2250 5275 / (033) 2250-5048 e-Mail : [email protected] 222 ||| P a g e Notice Inviting e-Tender TABLE OF CONTENTS NOTICE INVITING e-TENDER .................................................................................................................................. 3 I. PRE-BID QUALIFICATIONS ............................................................................................ 4 1. Company Registration : ...................................................................................................................... 4 2. Undertaking Regarding Blacklisting : ................................................................................................. 4 3. Partnership Firm (if applicable) :........................................................................................................ 4 4. Annual Turnover : ............................................................................................................................... 4 5. Work Experience : ............................................................................................................................... 4 6. PAN No. : .............................................................................................................................................