Niger Report HS Gender ENG Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NIGER: Carte Administrative NIGER - Carte Administrative

NIGER - Carte Administrative NIGER: Carte administrative Awbari (Ubari) Madrusah Légende DJANET Tajarhi /" Capital Illizi Murzuq L I B Y E !. Chef lieu de région ! Chef lieu de département Frontières Route Principale Adrar Route secondaire A L G É R I E Fleuve Niger Tamanghasset Lit du lac Tchad Régions Agadez Timbuktu Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti Diffa BARDAI-ZOUGRA(MIL) Dosso Maradi Niamey ZOUAR TESSALIT Tahoua Assamaka Tillabery Zinder IN GUEZZAM Kidal IFEROUANE DIRKOU ARLIT ! BILMA ! Timbuktu KIDAL GOUGARAM FACHI DANNAT TIMIA M A L I 0 100 200 300 kms TABELOT TCHIROZERINE N I G E R ! Map Doc Name: AGADEZ OCHA_SitMap_Niger !. GLIDE Number: 16032013 TASSARA INGALL Creation Date: 31 Août 2013 Projection/Datum: GCS/WGS 84 Gao Web Resources: www.unocha..org/niger GAO Nominal Scale at A3 paper size: 1: 5 000 000 TILLIA TCHINTABARADEN MENAKA ! Map data source(s): Timbuktu TAMAYA RENACOM, ARC, OCHA Niger ADARBISNAT ABALAK Disclaimers: KAOU ! TENIHIYA The designations employed and the presentation of material AKOUBOUNOU N'GOURTI I T C H A D on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion BERMO INATES TAKANAMATAFFALABARMOU TASKER whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations BANIBANGOU AZEY GADABEDJI TANOUT concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area ABALA MAIDAGI TAHOUA Mopti ! or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its YATAKALA SANAM TEBARAM !. Kanem WANZERBE AYOROU BAMBAYE KEITA MANGAIZE KALFO!U AZAGORGOULA TAMBAO DOLBEL BAGAROUA TABOTAKI TARKA BANKILARE DESSA DAKORO TAGRISS OLLELEWA -

Évaluation Des Ressources En Eau De L'aquifère Du Continental Intercalaire

Évaluation des ressources en eau de l’aquifère du Continental Intercalaire/Hamadien de la Région de Tahoua (bassin des Iullemeden, Niger) : impacts climatiques et anthropiques Abdel Kader Hassane Saley To cite this version: Abdel Kader Hassane Saley. Évaluation des ressources en eau de l’aquifère du Continental Inter- calaire/Hamadien de la Région de Tahoua (bassin des Iullemeden, Niger) : impacts climatiques et anthropiques. Géochimie. Université Paris Saclay (COmUE); Université de Niamey, 2018. Français. NNT : 2018SACLS192. tel-02089629 HAL Id: tel-02089629 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02089629 Submitted on 4 Apr 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Évaluation des ressources en eau de l’aquifère du Continental Intercalaire/Hamadien de la région de Tahoua (bassin des Iullemeden, Niger) : impacts climatiques et anthropiques : 2018SACLS192 NNT Cotutelle internationale de thèse de doctorat entre l'Université Paris-Saclay et l’Université Abdou Moumouni préparée à l’Université Paris-Sud et à l’Université Abdou Moumouni de Niamey -

Waho-2017-Annual-Report.Pdf

WAHO/XIX.AHM/2018/REP-doc. WEST AFRICAN HEALTH ORGANISATION ORGANISATION OUEST AFRICAINE DE LA SANTE ORGANIZACAO OESTE AFRICANA DA SAUDE 2017 ANNUAL REPORT March 2018 GLOSSARY AGM: Annual General Meeting AMRH: African Medicines Regulation Harmonization AHM: Assembly of Health Ministers AREF: Africa Excellence Research Fund ARVs: Anti-Retro Viral Drugs WB: World Bank BMGF: Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation GMP: Good Manufacturing Practices GPH: Good Practices in Health BCC: Behaviour Change Communication ECOWAS: Economic Community of West African States UTH: University Teaching Hospital NACI: National Advisory Committee on Immunization CORDS: Connecting Organizations for Regional Disease Surveillance SMC: Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention IDRC: International Development Research Center RCSDC: Regional Centre for Surveillance and Disease Control CTD: Common Technical Document DIHS2: District Health Information System 2 DDEC: Department of Disease and Epidemics Control DTC3: Diphtheria Tetanus Pertussis 3 DTCP: Diphtheria Tetanus Pertussis Poliomyelitis ECOWAS: Economic Community of West African States EQUIST: Equitable Strategies to save lives ERRRT: ECOWAS Regional Rapid Response Team FASFAF: Federation of French-speaking Africa Midwives Associations NITAG: National Immunization Technical Advisory Group HKI: Helen Keller International IATA: International Air Transport Association CBIs: Community-based Interventions IOTA: Tropical Ophthalmology Institute of Africa IPSAS: International Public Sector Accounting Standards IRSP: Regional Institute -

Domestic Private Sector Participation in Water and Sanitation: the Niger Case Study

WATER AND SANITATION PROGRAM: REPORT StrengtheningDelivering Water the Domestic Supply and Private Sanitation Sector (WSS) Services in Fragile States Domestic Private Sector Participation in Water and Sanitation: The Niger Case Study Taibou Adamou Maiga March 2016 The Water and Sanitation Program is a multi-donor partnership, part of the World Bank Group’s Water Global Practice, supporting poor people in obtaining affordable, safe, and sustainable access to water and sanitation services. About the Author WSP is a multi-donor partnership created in 1978 and administered by The author of this case study is Taibou Adamou Maiga, a the World Bank to support poor people in obtaining affordable, safe, Senior Water and Sanitation Specialist – GWASA. and sustainable access to water and sanitation services. WSP’s donors include Australia, Austria, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, the Acknowledgments Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, United States, and The author wishes to thank the Government of Niger, and the World Bank. particularly, the Ministry of Water and Sanitation for its time and support during the implementation of activities Standard Disclaimer: described in the report. He also wishes to especially thank This volume is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Jemima T. Sy, a Senior Infrastructure Specialist – GCPPP Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank. The findings, who provided important comments and guidance to enrich interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are entirely those this document. of the author and should not be attributed to the World Bank or its affiliated organizations, or to members of the Board of Executive The author of this document would like to express his Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. -

RIFT VALLEY FEVER in NIGER Risk Assessment

March 2017 ©FAO/Ado Youssouf ©FAO/Ado ANIMAL HEALTH RISK ANALYSIS ASSESSMENT No. 1 RIFT VALLEY FEVER IN NIGER Risk assessment SUMMARY In the view of the experts participating in this risk assessment, Rift Valley Fever (RVF) in Niger currently poses a medium risk (a mean score of 5.75 on a scale of 0 to 10) to human health, and a medium–high risk (a mean score of 6.5) to animal health. The experts take the view that RVF is likely / very likely (a 66%–99% chance range) to occur in Mali during this vector season. Its occurrence in the neighbouring countries of Benin, Burkina Faso and Nigeria is considered less probable – between unlikely (a 10%–30% chance) and as likely as not (a 33%–66% chance). The experts are of the opinion that RVF isunlikely to spread into Algeria, Libya or Morocco in the next three to five years. Animal movements, trade and changes in weather conditions are the main risk factors in RVF (re)occurring in West Africa and spreading to unaffected areas. Improving human health and the capacities of veterinary services to recognize the clinical signs of RVF in humans and animals are crucial for rapid RVF detection and response. Finally, to prevent human infection, the most feasible measure is to put in place communication campaigns for farmers and the general public. EPIDEMIOLOGICAL SITUATION FIGURE 1. Human cases of RVF in Niger Between 2 August and 9 October 2016, Niger reported 101 human cases of suspected RVF, including 28 deaths. All RVF cases were in Tchintabaraden and Abalak health districts in the Tahoua region (Figure 1). -

F:\Niger En Chiffres 2014 Draft

Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 1 Novembre 2014 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Direction Générale de l’Institut National de la Statistique 182, Rue de la Sirba, BP 13416, Niamey – Niger, Tél. : +227 20 72 35 60 Fax : +227 20 72 21 74, NIF : 9617/R, http://www.ins.ne, e-mail : [email protected] 2 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Pays : Niger Capitale : Niamey Date de proclamation - de la République 18 décembre 1958 - de l’Indépendance 3 août 1960 Population* (en 2013) : 17.807.117 d’habitants Superficie : 1 267 000 km² Monnaie : Francs CFA (1 euro = 655,957 FCFA) Religion : 99% Musulmans, 1% Autres * Estimations à partir des données définitives du RGP/H 2012 3 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 4 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Ce document est l’une des publications annuelles de l’Institut National de la Statistique. Il a été préparé par : - Sani ALI, Chef de Service de la Coordination Statistique. Ont également participé à l’élaboration de cette publication, les structures et personnes suivantes de l’INS : les structures : - Direction des Statistiques et des Etudes Economiques (DSEE) ; - Direction des Statistiques et des Etudes Démographiques et Sociales (DSEDS). les personnes : - Idrissa ALICHINA KOURGUENI, Directeur Général de l’Institut National de la Statistique ; - Ibrahim SOUMAILA, Secrétaire Général P.I de l’Institut National de la Statistique. Ce document a été examiné et validé par les membres du Comité de Lecture de l’INS. Il s’agit de : - Adamou BOUZOU, Président du comité de lecture de l’Institut National de la Statistique ; - Djibo SAIDOU, membre du comité - Mahamadou CHEKARAOU, membre du comité - Tassiou ALMADJIR, membre du comité - Halissa HASSAN DAN AZOUMI, membre du comité - Issiak Balarabé MAHAMAN, membre du comité - Ibrahim ISSOUFOU ALI KIAFFI, membre du comité - Abdou MAINA, membre du comité. -

World Bank Document

The World Bank First Laying the Foundation for Inclusive Development Policy Financing (P169830) Document of The World Bank Report No: PGD107 Public Disclosure Authorized INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION PROGRAM DOCUMENT FOR A PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT POLICY CREDIT IN THE AMOUNT OF EURO 156.9 MILLION (US$175.0 MILLION EQUIVALENT) AND Public Disclosure Authorized A PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT POLICY GRANT IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 126.9 MILLION (US$175.0 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE REPUBLIC OF NIGER FOR THE FIRST LAYING THE FOUNDATION FOR INCLUSIVE DEVELOPMENT POLICY FINANCING Public Disclosure Authorized November 13, 2019 Macroeconomics, Trade and Investment Global Practice Public Disclosure Authorized Africa Region This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. The World Bank First Laying the Foundation for Inclusive Development Policy Financing (P169830) Republic of Niger GOVERNMENT FISCAL YEAR JANUARY 1 – DECEMBER 31 CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective as of October 31, 2019) 0.72495813 0.89645899 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AfDB African Development Bank ANPER Agence Nigérienne pour la Promotion de l’Electrification Rurale (Niger Agency for the promotion of Rural Electrification) ARM Autorité de Régulation Multisectorielle (Multisectoral Regulatory Body) ASYCUDA Automated System for Customs Data AU African Union AUT Agence UMOA Titre (WAEMU Bond Agency) BCEAO Banque Centrale des Etats -

Projet D'amenagement Et De Bitumage De La Route Tamaske-Kalfou-Kolloma

Langage : French Original: French PROJET D’AMENAGEMENT ET DE BITUMAGE DE LA ROUTE TAMASKE-KALFOU-KOLLOMA Y COMPRIS LA BRETELLE DE TAMASKE-MARARRABA (63 KM) PAYS: REPUBLIQUE DU NGER RESUME DU PLAN ABREGE DE REINSTALLATION (PAR) Date: Mai 2019 Chef de Projet: M. SANGARE Ingénieur des Transports, Consultant RDGW3 - J.J. NYIRUBUTAMA Economiste des transports en Chef, RDGS4; L’Equipe du projet - E. C. KEMAYOU Spécialiste en Fragilité RDGWO ; - N. NANGMADJI Expert en sauvegarde environnementale et sociale - Consultant, SNSC/RDGW4 ; - T. OUEDRAGO Expert en Genre, Consultant RDGWO ; - R. SARR SAMB Spécialiste en Acquisitions, SNFI.l Chef de Division Régional : Jean Noel ILBOUDO Directeur Sectoriel: Amadou OUMAROU Directeur Général Adjoint : SERGE NGUESSAN Directeur General: Marie-Laure AKIN-OLUGBADE I. INTRODUCTION Le présent document résume le Plan d’Action de Réinstallation du projet d’aménagement et de bitumage de la route Tamaské-Kalfou-Kolloma y compris la bretelle de Tamaské-Mararraba (63 km) dans la région de Tahoua. Ce projet s’inscrit dans le cadre du Programme de la Renaissance acte 2 du gouvernement de la République du Niger, à travers lequel un Plan de Développement Économique et Social (PDES) 2017-2021 a été élaboré et adopté le gouvernement. Ce PDES prend en compte les projets et programmes prévus par la Stratégie Nationale des Transports en vue de renforcer et préserver le réseau routier national, un appareil économique pour un développement durable. Ainsi, le secteur des transports a été identifié comme un secteur prioritaire parmi les secteurs contribuant à la création de richesse et d’emploi. A cet effet, le gouvernement de la 7ème République a sollicité l’appui de la Banque Africaine de Développement afin de réaliser l’aménagement et le bitumage du tronçon Tamaské-Kalfou-Kolloma y compris la bretelle de Tamaské – Mararraba dans la région de Tahoua. -

Arrêt N° 012/11/CCT/ME Du 1Er Avril 2011 LE CONSEIL

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER Fraternité – Travail – Progrès CONSEIL CONSTITUTIONNEL DE TRANSITION Arrêt n° 012/11/CCT/ME du 1er Avril 2011 Le Conseil Constitutionnel de Transition statuant en matière électorale en son audience publique du premier avril deux mil onze tenue au Palais dudit Conseil, a rendu l’arrêt dont la teneur suit : LE CONSEIL Vu la Constitution ; Vu la proclamation du 18 février 2010 ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-01 du 22 février 2010 modifiée portant organisation des pouvoirs publics pendant la période de transition ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-096 du 28 décembre 2010 portant code électoral ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-038 du 12 juin 2010 portant composition, attributions, fonctionnement et procédure à suivre devant le Conseil Constitutionnel de Transition ; Vu le décret n° 2011-121/PCSRD/MISD/AR du 23 février 2011 portant convocation du corps électoral pour le deuxième tour de l’élection présidentielle ; Vu l’arrêt n° 01/10/CCT/ME du 23 novembre 2010 portant validation des candidatures aux élections présidentielles de 2011 ; Vu l’arrêt n° 006/11/CCT/ME du 22 février 2011 portant validation et proclamation des résultats définitifs du scrutin présidentiel 1er tour du 31 janvier 2011 ; Vu la lettre n° 557/P/CENI du 17 mars 2011 du Président de la Commission Electorale Nationale Indépendante transmettant les résultats globaux provisoires du scrutin présidentiel 2ème tour, aux fins de validation et proclamation des résultats définitifs ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 028/PCCT du 17 mars 2011 de Madame le Président du Conseil constitutionnel portant -

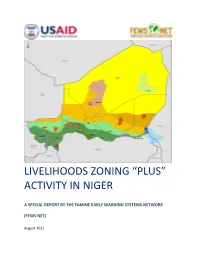

Livelihoods Zoning “Plus” Activity in Niger

LIVELIHOODS ZONING “PLUS” ACTIVITY IN NIGER A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) August 2011 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 4 National Livelihoods Zones Map ................................................................................................................... 6 Livelihoods Highlights ................................................................................................................................... 7 National Seasonal Calendar .......................................................................................................................... 9 Rural Livelihood Zones Descriptions ........................................................................................................... 11 Zone 1: Northeast Oases: Dates, Salt and Trade ................................................................................... 11 Zone 2: Aïr Massif Irrigated Gardening ................................................................................................ 14 Zone 3 : Transhumant and Nomad Pastoralism .................................................................................... 17 Zone 4: Agropastoral Belt ..................................................................................................................... -

Health Sector Reform in Africa: Lessons Learned

Health Sector Reform in Africa: Lessons Learned Dayl Donaldson March 1994 Data for Decision Making Project DDM Data for Department of Population and International Health Decision Harvard School of Public Health Making Boston, Massachusetts Data for Decision Making Project i Table of Contents Executive Summary.............................................................................................1 Introduction .......................................................................................................2 Nonproject Assistance Programs in the Health Sector ..............................................3 World Bank Health Sector Conditionality .....................................................3 USAID Health Sector Grants ......................................................................4 Factors Influencing Success or Failure of Nonproject Assistance ............................. 10 Environmental Factors ............................................................................ 10 Institutional Factors ................................................................................ 12 Ministry of Health .................................................................................. 13 Design Factors ....................................................................................... 14 Conclusion ....................................................................................................... 19 Bibliography .................................................................................................... -

West Africa Fy2012

FACT SHEET #1, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2012 SEPTEMBER 30, 2012 DISASTER RISK REDUCTION – WEST AFRICA OVERVIEW Many of the 21 countries1 in the West Africa region face recurrent complex emergencies, frequent food insecurity, sustained prevalence of acute malnutrition, cyclical drought, seasonal floods, and disease outbreaks, resulting in significant challenges to at-risk populations. Many cities in the region have rapidly expanded, often in areas prone to floods, landslides, and other natural hazards, causing urban growth to outpace the capacity of local authorities to respond to disasters. Conflict also scatters populations, triggering large-scale displacement that multiplies the vulnerabilities of those forcibly uprooted, who often lack access to resources, employment, and basic services. USAID’s Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance (USAID/OFDA) not only responds to disasters, but also funds disaster risk reduction (DRR) programs to build the capacity of communities to prepare for and respond to emergencies. USAID/OFDA’s DRR activities in West Africa during FY 2012 sought to reduce the risks and effects of acute malnutrition, food insecurity, displacement, and epidemics through programs that decrease household fragility and increase resilience to future shocks by addressing the root causes of recurrent emergencies in the region. During FY 2012, USAID/OFDA provided more than $52 million for DRR projects throughout West Africa, including programs that integrate DRR with disaster response. FY 2012 DRR FUNDING IN WEST AFRICA Stand-Alone DRR Programs in West Africa (see pages 1-3) $461,684 Programs that Integrate DRR with Disaster Response2 (see page 3-12) $51,730,748 TOTAL DRR Funding in West Africa $52,192,432 STAND-ALONE DRR PROGRAMS IN WEST AFRICA In FY 2012, USAID/OFDA’s West Africa team provided more than $460,000 for stand-alone DRR initiatives that improve preparedness and aim to mitigate and prevent the worst impacts of disasters.