AMS389 27 03 2001-2002 Lowres.474012B.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Skull of the Upper Cretaceous Snake Dinilysia Patagonica Smith-Woodward, 1901, and Its Phylogenetic Position Revisited

Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2012, 164, 194–238. With 24 figures The skull of the Upper Cretaceous snake Dinilysia patagonica Smith-Woodward, 1901, and its phylogenetic position revisited HUSSAM ZAHER1* and CARLOS AGUSTÍN SCANFERLA2 1Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de São Paulo, Avenida Nazaré 481, Ipiranga, 04263-000, São Paulo, SP, Brasil 2Laboratorio de Anatomía Comparada y Evolución de los Vertebrados. Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales ‘Bernardino Rivadavia’, Av. Angel Gallardo 470 (1405), Buenos Aires, Argentina Received 23 April 2010; revised 5 April 2011; accepted for publication 18 April 2011 The cranial anatomy of Dinilysia patagonica, a terrestrial snake from the Upper Cretaceous of Argentina, is redescribed and illustrated, based on high-resolution X-ray computed tomography and better preparations made on previously known specimens, including the holotype. Previously unreported characters reinforce the intriguing mosaic nature of the skull of Dinilysia, with a suite of plesiomorphic and apomorphic characters with respect to extant snakes. Newly recognized plesiomorphies are the absence of the medial vertical flange of the nasal, lateral position of the prefrontal, lizard-like contact between vomer and palatine, floor of the recessus scalae tympani formed by the basioccipital, posterolateral corners of the basisphenoid strongly ventrolaterally projected, and absence of a medial parietal pillar separating the telencephalon and mesencephalon, amongst others. We also reinterpreted the structures forming the otic region of Dinilysia, confirming the presence of a crista circumfenes- tralis, which represents an important derived ophidian synapomorphy. Both plesiomorphic and apomorphic traits of Dinilysia are treated in detail and illustrated accordingly. Results of a phylogenetic analysis support a basal position of Dinilysia, as the sister-taxon to all extant snakes. -

Snakes of the Siwalik Group (Miocene of Pakistan): Systematics and Relationship to Environmental Change

Palaeontologia Electronica http://palaeo-electronica.org SNAKES OF THE SIWALIK GROUP (MIOCENE OF PAKISTAN): SYSTEMATICS AND RELATIONSHIP TO ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE Jason J. Head ABSTRACT The lower and middle Siwalik Group of the Potwar Plateau, Pakistan (Miocene, approximately 18 to 3.5 Ma) is a continuous fluvial sequence that preserves a dense fossil record of snakes. The record consists of approximately 1,500 vertebrae derived from surface-collection and screen-washing of bulk matrix. This record represents 12 identifiable taxa and morphotypes, including Python sp., Acrochordus dehmi, Ganso- phis potwarensis gen. et sp. nov., Bungarus sp., Chotaophis padhriensis, gen. et sp. nov., and Sivaophis downsi gen. et sp. nov. The record is dominated by Acrochordus dehmi, a fully-aquatic taxon, but diversity increases among terrestrial and semi-aquatic taxa beginning at approximately 10 Ma, roughly coeval with proxy data indicating the inception of the Asian monsoons and increasing seasonality on the Potwar Plateau. Taxonomic differences between the Siwalik Group and coeval European faunas indi- cate that South Asia was a distinct biogeographic theater from Europe by the middle Miocene. Differences between the Siwalik Group and extant snake faunas indicate sig- nificant environmental changes on the Plateau after the last fossil snake occurrences in the Siwalik section. Jason J. Head. Department of Paleobiology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, P.O. Box 37012, Washington, DC 20013-7012, USA. [email protected] School of Biological Sciences, Queen Mary, University of London, London, E1 4NS, United Kingdom. KEY WORDS: Snakes, faunal change, Siwalik Group, Miocene, Acrochordus. PE Article Number: 8.1.18A Copyright: Society of Vertebrate Paleontology May 2005 Submission: 3 August 2004. -

Naracoorte Caves National Park

Department for Environment and Heritage Naracoorte Caves National Park Australian Fossil Mammal Site World Heritage Area www.environment.sa.gov.au Naracoorte Caves Vegetation Wonambi Fossil Centre National Par The vegetation is predominantly Brown Stringybark Step through the doors of the Wonambi Fossil Australian Fossil Mammal Site on the limestone ridge, with River Red Gum lining the Centre into an ancient world where megafauna World Heritage Area banks of the Mosquito Creek. The understorey on the once roamed. The display in the Wonambi Fossil ridge is bracken fern over a diverse array of orchids Centre ‘brings to life’ the megafauna fossils found in the Naracoorte Caves. The self-guided walk Naracoorte Caves National Park covers that flower during spring. through the simulated forest and swampland is approximately 600 hectares of limestone wheelchair accessible and suitable for all ages. ranges and is situated in the Some of the park was cleared for pine forests in the south-east of South Australia, mid 1800s, with other exotic species planted around The Flinders University Gallery has information 10 km south of Naracoorte. the caves. Many of the pines have now been cleared and areas revegetated with endemic species. The panels depicting the various sciences studied at Naracoorte, and touch screen computers to answer The area was first gardens now consist of native plants although a few questions you may have relating to the Wonambi dedicated a forestry of the historic trees remain. Fossil Centre and the fossils of Naracoorte Caves. reserve in 1882, with Fauna the first caretaker Southern employed to look Bentwing Bat The National Parks Code after the caves in The most common marsupial seen at Naracoorte is the Western Grey Kangaroo. -

A Diverse Snake Fauna from the Early Eocene of Vastan Lignite Mine, Gujarat, India

A diverse snake fauna from the early Eocene of Vastan Lignite Mine, Gujarat, India JEAN−CLAUDE RAGE, ANNELISE FOLIE, RAJENDRA S. RANA, HUKAM SINGH, KENNETH D. ROSE, and THIERRY SMITH Rage, J.−C., Folie, A., Rana, R.S., Singh, H., Rose, K.D., and Smith, T. 2008. A diverse snake fauna from the early Eocene of Vastan Lignite Mine, Gujarat, India. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 53 (3): 391–403. The early Eocene (Ypresian) Cambay Formation of Vastan Lignite Mine in Gujarat, western India, has produced a di− verse assemblage of snakes including at least ten species that belong to the Madtsoiidae, Palaeophiidae (Palaeophis and Pterosphenus), Boidae, and several Caenophidia. Within the latter taxon, the Colubroidea are represented by Russel− lophis crassus sp. nov. (Russellophiidae) and by Procerophis sahnii gen. et sp. nov. Thaumastophis missiaeni gen. et sp. nov. is a caenophidian of uncertain family assignment. At least two other forms probably represent new genera and spe− cies, but they are not named; both appear to be related to the Caenophidia. The number of taxa that represent the Colubroidea or at least the Caenophidia, i.e., advanced snakes, is astonishing for the Eocene. This is consistent with the view that Asia played an important part in the early history of these taxa. The fossils come from marine and continental levels; however, no significant difference is evident between faunas from these levels. The fauna from Vastan Mine in− cludes highly aquatic, amphibious, and terrestrial snakes. All are found in the continental levels, including the aquatic palaeophiids, whereas the marine beds yielded only two taxa. -

Burrowing Into the Inner World of Snake Evolution 15 March 2018

Burrowing into the inner world of snake evolution 15 March 2018 "So, we compared the inner ears of Yurlunggur and Wonambi to those of 81 snakes and lizards of known ecological habits," Dr. Palci says. "We concluded that Yurlunggur was partly adapted to burrow underground, while Wonambi was more of a generalist, likely at ease in more diverse environments." These interpretations are supported by other features of the skull and skeleton of the two snakes, as well as by palaeoclimate, which implies they had quite different environmental preferences (Wonambi preferred much cooler and drier Credit: Flinders University habitats). Dr. Palci is specialising in the origin, phylogenetic relationships, and evolutionary history and Looking inside the head of a snake is so much diversification of major taxonomic groups, with a easier when the snake is a fossil. special focus on living and fossil squamates (a group of reptiles that includes lizards, Flinders University and South Australian Museum amphisbaenians, and snakes). postdoctoral researcher Alessandro Palci and other evolutionary palaeontology experts have Squamate reptiles, with over 9,000 known species, used high-resolution computer tomography (CT) to represent an ideal study group to investigate look inside the inner ears of two important evolution. Australian fossil snakes – the 23 million-year-old Yurlunggur from northern Australia, and the much The research revolves around several projects in younger Wonambi, from southern Australia, which collaborations with researchers at the South went extinct only about 50,000 years ago. Australian Museum, Flinders University, the University of Adelaide and University of Alberta. These snakes are important because they are considered close to the base of the evolutionary Digital images (see below) of the fossil snakes tree of snakes, and can thus provide some Yurlunggur and Wonambi reveal the inner ear information on what the earliest snakes looked like mostly consists of a large central portion termed and how they lived, says Dr. -

THYLACOLEO CARNIFEX and the NARACOORTE CAVES Michael Curry, Liz Reed1,2 and Steve Bourne3

RESEARCH CATCHING the MARSUPIAL ‘LION’ by the TAIL: THYLACOLEO CARNIFEX and the NARACOORTE CAVES Michael Curry, Liz Reed1,2 and Steve Bourne3 1School of Physical Sciences, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA, Australia; 2School of Biological Sciences, Flinders University, Bedford Park, SA, Australia; 3Naracoorte Lucindale Council, Naracoorte, SA, Australia. “Thylacoleo exemplifies the simplest and most effective dental machinery for predatory life and carnivorous diet known in the Mammalian class. It is the extreme modification, to this end, of the Diprotodont type of Marsupialia.” Owen (1866) Introduction defending Thylacoleo as “A very gentle beast, and of good conscience” (Macleay 1859). Macleay based his Of all the extinct Australian Pleistocene megafauna argument on Thylacoleo’s relationship with other species, Thylacoleo carnifex (the marsupial ‘lion’) has Diprotodont marsupials, most of which are herbivores. captured the imagination and interest of people more Gerard Krefft, Curator of the Australian Museum, was than any other. Perhaps it is the allure of its predatory almost equally as unimpressed with Thylacoleo’s habits, (Australia’s Pleistocene answer to T. rex); or the carnivory, opining that it “…was not much more intriguing notion that it used caves as dens (Lundelius, carnivorous than the Phalangers (possums) of present 1966 ). It is certainly an enigma and, as Owen (1866) time.” (Krefft, 1866). Owen, meanwhile, had received an suggested, an extreme and meat-eating version of the almost complete skull from the Darling Downs, in otherwise herbivorous diprotodont marsupials. Queensland and published a more detailed paper, Spectacular fossil finds over the past few decades have further describing the skull and teeth of Thylacoleo, put to rest much of the speculation regarding its habits acknowledging its diprotodont affiliation but more and morphology. -

1 TABLE S1 Global List of Extinct and Extant Megafaunal Genera By

Supplemental Material: Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst.. 2006. 37:215-50 doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132415 Late Quaternary Extinctions: State of the Debate Koch and Barnosky TABLE S1 Global list of extinct and extant megafaunal genera by continent. STATUS TAXON TIME AFRICA Mammalia Carnivora Felidae Acinonyx Panthera Hyaenidae Crocuta Hyaena Ursidae Ursusa Primates Gorilla Proboscidea Elephantidae C Elephas <100 Loxodonta Perissodactyla Equidae S Equus <100 E Hipparion <100 Rhinocerotidae Ceratotherium Diceros E Stephanorhinus <100 Artiodactyla Bovidae Addax Ammotragus Antidorcas Alcelaphus Aepyceros C Bos 11.5-0 Capra Cephalopus Connochaetes Damaliscus Gazella S Hippotragus <100 Kobus E Rhynotragus/Megalotragus 11.5-0 Oryx E Pelorovis 11.5-0 E Parmulariusa <100 Redunca Sigmoceros Syncerus Taurotragus Tragelaphus Camelidae C Camelus <100 1 Supplemental Material: Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst.. 2006. 37:215-50 doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132415 Late Quaternary Extinctions: State of the Debate Koch and Barnosky Cervidae E Megaceroides <100 Giraffidae S Giraffa <100 Okapia Hippopotamidae Hexaprotodon Hippopotamus Suidae Hylochoerus Phacochoerus Potamochoerus Susa Tubulidenta Orycteropus AUSTRALIA Reptilia Varanidae E Megalania 50-15.5 Meiolanidae E Meiolania 50-15.5 E Ninjemys <100 Crocodylidae E Palimnarchus 50-15.5 E Quinkana 50-15.5 Boiidae? E Wonambi 100-50 Aves E Genyornis 50-15.5 Mammalia Marsupialia Diprotodontidae E Diprotodon 50-15.5 E Euowenia <100 E Euryzygoma <100 E Nototherium <100 E Zygomaturus 100-50 Macropodidae S Macropus 100-50 E Procoptodon <100 E Protemnodon 50-15.5 E Simosthenurus 50-15.5 E Sthenurus 100-50 Palorchestidae E Palorchestes 50-15.5 Thylacoleonidae E Thylacoleo 50-15.5 Vombatidae S Lasiorhinus <100 E Phascolomys <100 E Phascolonus 50-15.5 E Ramsayia <100 2 Supplemental Material: Annu. -

Climate Change Frames Debate Over the Extinction of Megafauna in Sahul (Pleistocene Australia-New Guinea) Stephen Wroea,B, Judith H

PERSPECTIVE PERSPECTIVE Climate change frames debate over the extinction of megafauna in Sahul (Pleistocene Australia-New Guinea) Stephen Wroea,b, Judith H. Fielda,1, Michael Archera, Donald K. Graysonc, Gilbert J. Priced, Julien Louysd, J. Tyler Faithe, Gregory E. Webbd, Iain Davidsonf, and Scott D. Mooneya aSchool of Biological, Earth, and Environmental Sciences, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia; bSchool of Engineering, University of Newcastle, NSW 2308, Australia; cDepartment of Anthropology and Quaternary Research Center, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195; dSchool of Earth Sciences, The University of Queensland, St. Lucia, QLD 4072, Australia; eSchool of Social Science, The University of Queensland, St. Lucia, QLD 4072, Australia; and fSchool of Humanities, University of New England, Armidale, NSW 2351, Australia Edited by James O’Connell, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, and approved April 9, 2013 (received for review February 12, 2013) Around 88 large vertebrate taxa disappeared from Sahul sometime during the Pleistocene, with the majority of losses (54 taxa) clearly taking place within the last 400,000 years. The largest was the 2.8-ton browsing Diprotodon optatum, whereas the ∼100- to 130-kg marsupial lion, Thylacoleo carnifex, the world’s most specialized mammalian carnivore, and Varanus priscus, the largest lizard known, were formidable predators. Explanations for these extinctions have centered on climatic change or human activities. Here, we review the evidence and argu- ments for both. Human involvement in the disappearance of some species remains possible but unproven. Mounting evidence points to the loss of most species before the peopling of Sahul (circa 50–45 ka) and a significant role for climate change in the disappearance of the continent’s megafauna. -

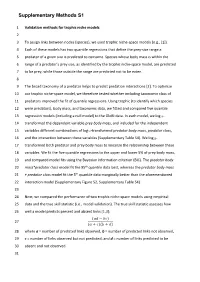

Supplementary Methods S1

1 Validation methods for trophic niche models 2 3 To assign links between nodes (species), we used trophic niche-space models (e.g., [1]). 4 Each of these models has two quantile regressions that define the prey-size range a 5 predator of a given size is predicted to consume. Species whose body mass is within the 6 range of a predator’s prey size, as identified by the trophic niche-space model, are predicted 7 to be prey, while those outside the range are predicted not to be eaten. 8 9 The broad taxonomy of a predator helps to predict predation interactions [2]. To optimize 10 our trophic niche-space model, we therefore tested whether including taxonomic class of 11 predators improved the fit of quantile regressions. Using trophic (to identify which species 12 were predators), body mass, and taxonomic data, we fitted and compared five quantile 13 regression models (including a null model) to the GloBI data. In each model, we log10- 14 transformed the dependent variable prey body mass, and included for the independent 15 variables different combinations of log10-transformed predator body mass, predator class, 16 and the interaction between these variables (Supplementary Table S4). We log10- 17 transformed both predator and prey body mass to linearize the relationship between these 18 variables. We fit the five quantile regressions to the upper and lower 5% of prey body mass, 19 and compared model fits using the Bayesian information criterion (BIC). The predator body 20 mass*predator class model fit the 95th quantile data best, whereas the predator body mass 21 + predator class model fit the 5th quantile data marginally better than the aforementioned 22 interaction model (Supplementary Figure S2, Supplementary Table S4). -

Natureworks All Things Prehistoric Catalogue

NATUREWORKS PREHISTORIC COLLECTION [email protected] www.natureworks.com.au 07 3289 7555 DINOSAURS Natureworks collection of Life-size Prehistoric Art Natureworks Pty Ltd is a Brisbane based exhibition and fabrication company which applies museum techniques commercially. It was started by David Joffe an ex Queensland museum preparator as a vehicle to pursue his interest in the natural world. Natureworks specialises in wildlife sculpture of all things PREHISTORIC, EXTINCT and ENDANGERED. His team of creative sculptors is prototyping hundreds of life-size 3D wildlife replicas in fibreglass produced to museum standard, for distribution worldwide. This unique collection of animal art now numbers over 2000 spectacular items of interest to museums, zoos and naturalists from all over the world who are reconstructing themed environments to educate, entertain and delight. www.natureworks.com.au Triceratops Skeleton On the drawing board for 2020 W: natureworks.com.au P: 07 3289 7555 E: [email protected] Prehistoric Collection 1 PREHISTORIC ARCHWAY Prehistoric Archway Prehistoric entry statement showing embedded fossil detail Archway Installed Business Name Here The archway provides a themed entry statement to any dinosaur themed project such as a mini- golf, dinosaur park, a museum exhibit or a black-light prehistoric landscape display. Natureworks has created the dream fossil stone feature filled with perfectly exposed castings to fascinate those who pass through its “ancient” arches. W: natureworks.com.au P: 07 3289 7555 E: [email protected] -

Facilitated Program

Western Australian Museum Perth 4 - 7 Middle Childhood Fossil Forensics: Magnificent Megafauna Facilitated Program Overview : Investigate the events of a real Museum expedition to an underground cave on the Nullarbor Plain to recover skeletal remains of a unique marsupial predator. Meet the Museum’s marvellous megafauna and unravel the mystery behind their extinction. Duration : One hour facilitated experience with a Museum Education Officer. Please allow approximately 45 minutes additional time for self-guided gallery exploration using Student Activity sheets and Adult Helper Guide. What your class will experience: Learn about the discovery of skeletal remains of an extinct Australian marsupial predator. Investigate each stage of the unique and significant Museum project to recover and study the remains. Participate in hands-on activities that reflect the examination and reconstruction of the animal’s skeleton. Explore theories of megafauna extinction. Excursion Booking and Enquiries: For enquiries and bookings please contact: Western Australian Museum – Perth Education Phone: 9427 2792 Fax: 9427 2883 Email: [email protected] Western Australian Museum Teacher Resource: Fossil Forensics – Magnificent Megafauna www.museum.wa.gov.au © 2010 Contents Teacher Resource Links 3 Curriculum Galleries At the Museum 4 Facilitated Program Self-guided Experience Related Museum Resources At School 6 Classroom Activities DVD Activities Related Classroom Resources Adult Helper Guide 9 Photocopy Fossil Forensics – Magnificent Megafauna Adult Helper Guide (for every adult) Student Activity Sheets 14 Photocopy Fossil Forensics – Magnificent Megafauna Student Activity sheets (for every student) Western Australian Museum Teacher Resource: Fossil Forensics – Magnificent Megafauna www.museum.wa.gov.au © 2010 2 Links Curriculum Life and Living Science Students understand their own biology and that of other living things and recognise the interdependence of life. -

Downloaded from the NBCI Genbank Database Emerging from Hibernation in Order to Bask, Mate, and (See Additional File 9)

Hsiang et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology (2015) 15:87 DOI 10.1186/s12862-015-0358-5 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access The origin of snakes: revealing the ecology, behavior, and evolutionary history of early snakes using genomics, phenomics, and the fossil record Allison Y Hsiang1*, Daniel J Field1,2, Timothy H Webster3, Adam DB Behlke1, Matthew B Davis1, Rachel A Racicot1 and Jacques A Gauthier1,4 Abstract Background: The highly derived morphology and astounding diversity of snakes has long inspired debate regarding the ecological and evolutionary origin of both the snake total-group (Pan-Serpentes) and crown snakes (Serpentes). Although speculation abounds on the ecology, behavior, and provenance of the earliest snakes, a rigorous, clade-wide analysis of snake origins has yet to be attempted, in part due to a dearth of adequate paleontological data on early stem snakes. Here, we present the first comprehensive analytical reconstruction of the ancestor of crown snakes and the ancestor of the snake total-group, as inferred using multiple methods of ancestral state reconstruction. We use a combined-data approach that includes new information from the fossil record on extinct crown snakes, new data on the anatomy of the stem snakes Najash rionegrina, Dinilysia patagonica,andConiophis precedens, and a deeper understanding of the distribution of phenotypic apomorphies among the major clades of fossil and Recent snakes. Additionally, we infer time-calibrated phylogenies using both new ‘tip-dating’ and traditional node-based approaches, providing new insights on temporal patterns in the early evolutionary history of snakes. Results: Comprehensive ancestral state reconstructions reveal that both the ancestor of crown snakes and the ancestor of total-group snakes were nocturnal, widely foraging, non-constricting stealth hunters.