01Belbruno Ch01 1-4.Qxd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploration of the Moon

Exploration of the Moon The physical exploration of the Moon began when Luna 2, a space probe launched by the Soviet Union, made an impact on the surface of the Moon on September 14, 1959. Prior to that the only available means of exploration had been observation from Earth. The invention of the optical telescope brought about the first leap in the quality of lunar observations. Galileo Galilei is generally credited as the first person to use a telescope for astronomical purposes; having made his own telescope in 1609, the mountains and craters on the lunar surface were among his first observations using it. NASA's Apollo program was the first, and to date only, mission to successfully land humans on the Moon, which it did six times. The first landing took place in 1969, when astronauts placed scientific instruments and returnedlunar samples to Earth. Apollo 12 Lunar Module Intrepid prepares to descend towards the surface of the Moon. NASA photo. Contents Early history Space race Recent exploration Plans Past and future lunar missions See also References External links Early history The ancient Greek philosopher Anaxagoras (d. 428 BC) reasoned that the Sun and Moon were both giant spherical rocks, and that the latter reflected the light of the former. His non-religious view of the heavens was one cause for his imprisonment and eventual exile.[1] In his little book On the Face in the Moon's Orb, Plutarch suggested that the Moon had deep recesses in which the light of the Sun did not reach and that the spots are nothing but the shadows of rivers or deep chasms. -

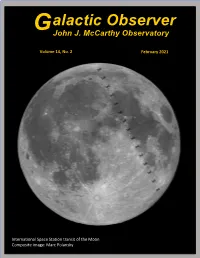

Alactic Observer

alactic Observer G John J. McCarthy Observatory Volume 14, No. 2 February 2021 International Space Station transit of the Moon Composite image: Marc Polansky February Astronomy Calendar and Space Exploration Almanac Bel'kovich (Long 90° E) Hercules (L) and Atlas (R) Posidonius Taurus-Littrow Six-Day-Old Moon mosaic Apollo 17 captured with an antique telescope built by John Benjamin Dancer. Dancer is credited with being the first to photograph the Moon in Tranquility Base England in February 1852 Apollo 11 Apollo 11 and 17 landing sites are visible in the images, as well as Mare Nectaris, one of the older impact basins on Mare Nectaris the Moon Altai Scarp Photos: Bill Cloutier 1 John J. McCarthy Observatory In This Issue Page Out the Window on Your Left ........................................................................3 Valentine Dome ..............................................................................................4 Rocket Trivia ..................................................................................................5 Mars Time (Landing of Perseverance) ...........................................................7 Destination: Jezero Crater ...............................................................................9 Revisiting an Exoplanet Discovery ...............................................................11 Moon Rock in the White House....................................................................13 Solar Beaming Project ..................................................................................14 -

Lunar Trajectories

Transportation for Exploration: New Thoughts About Orbital Dynamics Ed Belbruno Innovative Orbital Design, Inc & Courant Insitiute(NYU) January 4, 2012 NASA FISO 1 Evolution of Astrodynamics Conic; Stable (Hohmann, 20s) (Hohmann transfers, Gravity assist(Voyager, Galileo)) Nonlinear; Stable (Apollo, 60s) Nonlinear; Unstable (ISEE-3, 70s) (Transfer to and from halo orbits, no utilization of fuel savings via dynamics – Farquhar …) Nonlinear; Unstable; Low Energy/Fuel (Hiten, 91) (First use of utilization of chaotic dynamics/manifolds to achieve new approach to space travel for ballistic capture(EB, 86, 91) and for the study of halo orbit dynamics (Llibre-Simo, 85 – Genesis, 2001) Weak Stability Boundary Theory (EB 86) 2 Hohmann Transfer Conic, Stable – 2-body 3 Figure Eight(Apollo) Nonlinear, Stable – 3-body 4 ISEEC-3 Nonlinear-Unstable – 4 body 5 Ballistic Capture Transfers Weak Stability Boundary Theory(EB 86) • Way to transfer to the Moon, and other bodies, where no DeltaV is needed for capture • New methodology to trajectory design • Thought in 1985 to be impossible 6 Background • Capture Problem Earth -> Moon (LEO -> LLO) • Hohmann Transfer: Fast (3days), Fuel Hog (Need to slow down! 1 km/s to be captured – large maneuver ) Risky Used in Apollo 7 Idea of Achieving Ballistic Capture • Sneak up on Moon - very carefully (next figure A-B-C-D) • Like a surfer catching a wave • Want to ride the „gravity transition(weak stability) boundary‟ between the Earth-Moon-Sun 8 Top – Lagrange points Bottom – Sneaking up on Moon 9 Ballistic capture is chaotic (chaos – leaf blowing in wind) 10 • WSB – generalization of Lagrange points • Forces(GM, GE, CF) balance while spacecraft moving wrt Earth-Moon (L-points – forces balance for spacecraft fixed wrt Earth-Moon) • Get a multi-dimensional region about Moon. -

![VOWOX^ >OMRXYVYQSO] PY\ >\KTOM^Y\C .O]SQX PY\ 6 XK](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7799/vowox-omrxyvyqso-py-ktom-y-c-o-sqx-py-6-xk-777799.webp)

VOWOX^ >OMRXYVYQSO] PY\ >\KTOM^Y\C .O]SQX PY\ 6 XK

!" #$! %&#! & ' ($ ! # "" !" ($ ' ) ' ! ## * # ! '! ! " !" !#$! !&#! & ' ! & !+ ,&! &-&# ! !.,/0! & ! 1 !* && 2 ! $# ! " ! ! # #! !2 #2! ! "2 $ & ' ! * !#$! %&#! & ' + ! )'#$! + ! + # #& &$# !&#! -&# !#$! -&# ! ) & $ !) %$% $ % &$ ) &&' * $% $ ,$ + ' $$ % &+ !$ && 6 !"##$ % & $ ' ) ! & $'/ $& $ ($ % & ) % $ % ( & & $ ! * $ + (* ,$ +) & %+($ $$ R(& $+ (+ $ '- % (* ,$ $ $ 6 ) & ' + ) & * $$%& . $ 7)' * $ *$ 6 ) & $ & )+$&( )% * $ ( %& $ % ( & ,$ +) & & + $ &+& $%' *(! $ $6 / 0& & $ 11#' & $&)&+& ! 6 ) & ,$ +) & % $ $+ ) & $ % ( &*&&% $! 6 ) $ %& % & $ R ! *&& & ( & + $$ & & +& 2& + ,$' 0& +! ) & 2& + $& & + ! !$'' $ )$& & + & &% ! % ) 3( * ) + $ $ $! *% *+ $ + & $ +' 4 &+! ) & $* * !% $ & $ R& $($& &$ &$& *)$ +$ )$ ) (% & $ )$& & +' $ % $ & $ 3 *4 #$! + ! + !&.40* 456 & # $ !& 3 *5 !& " $'##$! 78* 3 *6 #$! + ! + !&.60* %&+ ):&R& *! ) (+ ! & % 6 $ ' ) (+ ' % / $! $& &&$ &! & $ + % $ $$ ,$ +) & 2& $ $ ) & $%& $ ) + ' % & ( &'$ (!& $* * & ) * % & $ &$& &$$ & & $ & * $ !$ )% % 8 $' $%$ & & ! ( ) # %) & $ $+' * )+- $ 4 $ ) ) ,$ % ! $! % ( 4## + * ) && + 6) &* &$%$ & & & &3 )) (+ &% $& & +' *#6) & )&$$ & & ' ) .$ ) - ( & %! * $$& ( ) % ' $& !% 6 & % ) ; -

The Planetary Report (Lssn 0736-3680) Is Published Six Times Yearly at Dozens of People Clamoring to Come

A Publication of THEPLANETA SOCIETY o ¢ 0 0 o o • 0-e Board of Directors FROI\II THE CARL SAGAN BRUCE MURRAY EDITOR President Vice President Director. Laboratory for Planetary Professor of Planetary Studies. Cornell University Science, California Institute of Technology LO UIS FR IEDMAN Executive Director JOSEPH RYAN O'Me/veny & Myers MICHAEL COLLINS Apollo 11 astronaut STEVEN SPIELBERG . he way we explore planets is chang its 1994 budget a new Discovery class of director and producer THOMAS O. PAINE former Administrator, NASA; HENRY J. TANNER T ing. Gone are the days when we could missions to cost no more than $150 mil Chairman, National financial consultant Commission on Space build space-traveling, multipurpose vehi lion each and to be accomplished in three Board of Advisors cles, load them with a profusion of years or less. Whether or not Congress instruments and send them off to answer will fund these missions remains to be DIANE ACKERMAN HANS MARK poet and author Chancellor. a multitude of scientific questions. seen. University of Texas System RICHARD BERENDZEN The Cassini mission to the saturnian Meanwhile, there are other concepts for educator and astrophysicist JAMES MICHENER author system, if it survives the congressional small spacecraft missions, many of which JACQUES BLAMONT Chief Scientist. Centre MARVIN MINSKY budget process, will probably be the last grew out of papers presented at the Soci National dEludes Spatia/es. France Toshiba Professor of Media Arts and Sciences, Massachusetts "flagship" mission launched for a long ety's workshop. Rather than bring you RAY BRADBURY Institute of Technology poet and author time. -

Celestial Mechanics Theory Meets the Nitty-Gritty of Trajectory Design

From SIAM News, Volume 37, Number 6, July/August 2004 Celestial Mechanics Theory Meets the Nitty-Gritty of Trajectory Design Capture Dynamics and Chaotic Motions in Celestial Mechanics: With Applications to the Construction of Low Energy Transfers. By Edward Belbruno, Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, 2004, xvii + 211 pages, $49.95. In January 1990, ISAS, Japan’s space research institute, launched a small spacecraft into low-earth orbit. There it separated into two even smaller craft, known as MUSES-A and MUSES-B. The plan was to send B into orbit around the moon, leaving its slightly larger twin A behind in earth orbit as a communications relay. When B malfunctioned, however, mission control wondered whether A might not be sent in its stead. It was less than obvious that this BOOK REVIEW could be done, since A was neither designed nor equipped for such a trip, and appeared to carry insufficient fuel. Yet the hope was that, by utilizing a trajectory more energy-efficient than the one By James Case planned for B, A might still reach the moon. Such a mission would have seemed impossible before 1986, the year Edward Belbruno discovered a class of surprisingly fuel-efficient earth–moon trajectories. When MUSES-B malfunctioned, Belbruno was ready and able to tailor such a trajectory to the needs of MUSES-A. This he did, in collaboration with J. Miller of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, in June 1990. As a result, MUSES-A (renamed Hiten) left earth orbit on April 24, 1991, and settled into moon orbit on October 2 of that year. -

STAIF Abstract Template

Japan’s Lunar Exploration Strategy and Its Role in International Coordination Jun’ichiro Kawaguchi JSPEC (JAXA Space Exploration Center), 3-1-1 Yoshinodai, Sagamihara, Kanagawa 229-8510, Japan. E-mail: [email protected], Phone: +81-420-759-8219, 8649 Abstract. JAXA’s Space Exploration Directorate: JAXA built its Lunar and Planetary Exploration Center (JSPEC) this April. JSPEC is doing not only the moon but planetary exploration encompassing from science to so-called exploration. JSPEC elaborates strategies of science and technology, program planning and promotion of Space Exploration activities through domestic and international collaborations. And at the same time, the Specific R&D activities for engineering and science development, operation and other related activities for spacecraft are also performed there, including the research and analysis of scientific and technical aspects for future missions. Simply speaking, the JSPEC of JAXA looks at both Exploration together with Science Missions. The activity includes the Moon, Mars and NEOs plus Primitive Bodies, and Atmospheric, Plasma and Surface environmental missions. Japan’s governmental Lunar Exploration study status The science WG under the SAC (Space Activity Commission, J. gov) concluded this January, and made a recommendation that the Japan’s Lunar and Planetary Exploration shall be performed in a programmatic manner at a certain interval. Along with this, the Solar Exploration Road Map study was completed this March, and the Lunar Architecture Study was preliminary done at JAXA this summer. This September, the Lunar Exploration WG was established under the SAC, and started the strategic discussion at the government level on how to go about the lunar exploration in Japan. -

Lems of the Orbit Determination for Nozomi Spacecraft

November 2001 37 Present status and future prob- lems of the orbit determination for Nozomi spacecraft Makoto Yoshikawa1 ([email protected]), Mamoru Sekido2, Noriyuki Kawaguchi3, Kenta Fujisawa3, Hideo Hanada4, Yusuke Kono4, Hisashi Hirabayashi1, Yasuhiro Murata1, Satoko Sawada-Satoh1, Kiyoaki 1 1 Figure 1. Nozomi spacecraft Wajima , Yoshiharu Asaki , Jun’ichiro Kawaguchi1, Hiroshi Yamakawa1, Takaji Kato1, Tsutomu Ichikawa1, and Takafumi 5 launched several spacecraft that went into inter- Ohnishi planetary space, such as “Sakigake” and “Suisei”. 1 From the point of orbital determination (OD), No- Institute of Space and Astronautical Science zomi is quite different from these previous ones be- (ISAS) cause the requirement for the OD accuracy is much 3-1-1 Yoshinodai, Sagamihara, Kanagawa higher. The maximum distance between Nozomi 229-8510, Japan × 5 2 and the earth is about 5 10 km in the near-earth Kashima Space Research Center phase and about 3 × 108 km in the interplanetary Communications Research Laboratory (CRL) phase. This indicates that the accurate OD is much 893-1 Hirai, Kashima, Ibaraki 314-0012, Japan 3 more difficult in the interplanetary phase than in National Astronomical Observatory (NAO) the near-earth phase. The OD group in ISAS has 2-21-1 Osawa, Mitaka, Tokyo 181-8588, Japan 4 been trying to obtain the much more accurate or- Mizusawa Astrogeodynamics Observatory bit for Nozomi. However, we find that there are National Astronomical Observatory several difficult problems in front of us. We will 2-12, Hoshigaoka, Mizusawa, Iwate 023-0861, mention these problems briefly in the section 4. Japan 5 Up to now (November 2001), there are several Fujitsu Limited events that are very critical to the orbital determi- 3-9-1 Nakase, Mihama-ku, Chiba-shi, Chiba nation of Nozomi. -

Landing Targets and Technical Subjects for SELENE-2

Landing Targets and Technical Subjects for SELENE-2 Kohtaro Matsumoto, Tatsuaki Hashimoto, Takeshi Hoshino, Sachiko Wakabayashi, Takahide Mizuno, Shujiro Sawai, and Jun'ichiro Kawaguchi JAXA / JSPEC 2007.10.23 ILEWG 1 JAXA’s Lunar Exploration SELENE-B Hiten & SELENE SELENE-2 Human Hagoromo SELENE-X Lunar 1990 ~ 2007.9 (Early 2010) Explo. SAC- -Lunar JAXA 2025 Explo. WG NASA VSE Lunar-A 図 Int’ Coop. SELENE-2 2007.10.23 ILEWG 2 Japanese Lander Concepts : SELENE-B to SELENE-2 • SELENE-B – Mission • Lunar science – Landing • Central peak of a large crater Copernicus • SELENE-2 Central Peak – Mission • Lunar science • Technology development • International cooperation – Landing : • Primary : ELR (Eternal Light Region) of polar region • Sub : Equatorial, or high latitudes South Pole & Shackleton Crator (D.B.J.Bussey et al) 2007.10.23 ILEWG 3 Characteristics of new Landing Target -- Quasi-ELR(eternal light region) – • for long term lunar activity – Long term scientific observation – Seismology, libration, . – Future lunar activities – Outpost, Observatory • Science – By : Long Term Seismometric Observation – of : Geology & Chronology, SPA – : Origin of Water/Ice – from : Astronomy • Utilization – PSR is very close for water/ice ISRU 2007.10.23 ILEWG 4 Landing Targets for SELENE-2 Polar Region (ELR) Mid Lattitude (Crater Central Hill) Tech. *Long term mission by *Direct link from ground merits solar power *Optical image role for Hazard *Low temperature change Avoidance *Hot temperature during day time Science *Water/Ice possibility at *Material from lunar inside PSR *SPA and far side *Samples from SPA Social *Inter. human lunar *Science driven exploration & outpost Subjects *Narrow Landing site *Night survival for long Moon to be *Low sun angle nights solved *Difficulty of direct comm. -

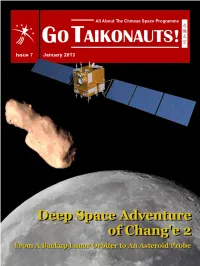

Chang'e Flying to the Moon

Issue 7 January 2013 All about the Chinese Space Programme GO TAIKONAUTS! Editor’s Note COVER STORY If you are a fan of the Chinese space pro- gramme, you must have heard about Brian Harvey, who is the first Western writer to publish a book on the Chinese space pro- gramme. We are very happy that Mr. Harvey contributed an article to Go Taikonauts! The article about Chinese ... page 2 Quarterly Report October - December 2012 Launch Events China made six space launches in the last three months of 2012, setting a new annual launch record of 19 and overtaking U.S. in number of suc- cessful annual space launches for the first time. In 2011, China also ... page 3 Deep Space Adventure of Chang’e 2 From A Backup Lunar Orbiter to An Asteroid Probe Observation Just before Chang’e 1 (CE-1)’s successful mission to the Moon was completed, Echo of the Curiosity in China China announced that they would send the second lunar probe Chang’e 2 (CE-2) The 6 August 2012 was a special day to an to the Moon in 2010. No one at that time could anticipate the surprises that CE-2 American-Chinese girl. She is Clara Ma, would bring a few years later since it was just a backup ... page 8 a 15-year-old middle school student from Lenexa, Kansas. She waited for this day for more than three years. In May 2009, History Ma won a NASA essay contest for naming the Mars Science Laboratory, the most Chang’e Flying to the Moon complicated machine .. -

Fuelling the Future of Mobility: Moon-Produced Space Propellants

May 2021 Fuelling the future of mobility: Moon-produced space propellants Go Beyond The forthcoming decade is expected to witness a wave of missions to the Moon and Mars, and fuel supply is a major challenge to make these travels economically sustainable. The difference in the required energy to launch from Earth and from the Moon is causing people to reconsider refuelling point positions (e.g. NHRO, Near Halo Rectilinear Orbit) and contemplate using space-produced propellants. A whole production and transport value chain would have to be established on the Moon. Initial investments are sizeable (~$7B) but an economic oportunity for space propellants should exist if launch costs from Earth do not fall too much below current SpaceX standards. Capex optimization and increased scale should further improve the competitiveness of space propellants. Positive outcomes for ’terrestrial‘ applications are also expected to be significant. Fuelling the future of mobility: Moon-produced space propellants The Case for Moon-Produced Propellants The next decade is expected to witness After 2024, NASA expects to set up a a boom in Lunar and Mars exploration. base camp on the moon (’Artemis Base Space-exploration- After the space race of the 60s, there has Camp’) to be a long-term foothold for lunar been an unprecedented resurgence of exploration, as well as a Moon-orbiting driven technologies unmanned Lunar and Mars missions since station (’Gateway’) on the NHRO (Near the end of the 90s, as well as the spread Rectilinear Halo Orbit) being a site for also have very of space programs to various countries. -

Ballistic Lunar Transfers to Near Rectilinear Halo Orbit: Operational Considerations

Ballistic Lunar Transfers to Near Rectilinear Halo Orbit: Operational Considerations Nathan L. Parrish1, Ethan W. Kayser2, Matthew J. Bolliger3, Michael R. Thompson4, Jeffrey S. Parker5, Bradley W. Cheetham6 Advanced Space LLC, 2100 Central Ave, Boulder, CO 80301 Diane C. Davis7 ai solutions, 2224 Bay Area Blvd #415, Houston, TX 77058 Daniel J. Sweeney8 NASA Johnson Space Center, Houston TX 77048 This paper presents a study of ballistic lunar transfer (BLT) trajectories from Earth launch to insertion into a near rectilinear halo orbit (NRHO). BLTs have favorable properties for uncrewed launches to orbits in the vicinity of the Moon, such as dramatically reduced spacecraft ΔV requirements. Results are described from a detailed set of related mission design and navigation studies: maneuver placement, tracking cadence, and statistical ΔV requirements for various navigation state errors. Monte Carlo analyses are presented which simulate BLT navigation with various DSN tracking schedules. These analyses are presented to inform future missions to NRHOs. I. Introduction A. Motivation The Gateway is proposed as the next human outpost in space; a proving ground near the Moon for deep space technologies and a staging location for missions beyond Earth orbit and to the lunar surface. As the Gateway is constructed over time, both crewed and uncrewed payloads will frequently travel to the spacecraft. Examples include elements of the Gateway itself as the spacecraft grows in size, logistics modules carrying supplies, Human Lander System (HLS) elements to support a crewed lunar landing, and the Orion crew vehicle. Minimizing the cost of transfer from Earth to the Gateway enables successful construction, operations, and exploration.